Chapter 6: Matching Mentors and Mentees

Overview

One of the advantages of informal mentoring is that would-be mentees can have as many bites at the cherry as they like until they find a relationship that works for them. In formal, structured programmes that is not so easy. Again, there have evolved some practical ground rules that avoid some of the worst problems:

-

Avoid ‘shotgun marriages' wherever possible. The least successful matches are typically those where the mentor and mentee feel they have been imposed upon each other. Next least successful are those where pairings are nominated by top management. If you cannot allow people some element of choice, at least make sure that participants understand how the matching process has been made. SmithKline Beecham, before merged to become GlaxoSmithKline, installed match-making software that included a variety of information about the mentee's learning needs, the mentor's experience and some general psychometric data intended to avoid strong clashes of learning styles.

The greatest level of buy-in from participants seems to come from giving the mentee a selection of three potential mentors, whom he or she can meet if he or she wishes. It is very rare for anyone to ask for more than the original three. Making it clear that mentees will make their selection according to the degree of rapport they feel and the closeness of match with their learning need seems to overcome most of the potential problems of mentors feeling turned down.

-

Equally, avoid giving people an unguided choice. Experience suggests that many people will select as a mentor someone whom they know well and get on with. Alternatively, they will seek a high-flyer on whose coat-tails they can hang. Neither is likely to lead to a successful mentoring relationship. Too much familiarity allows little grit in the oyster - the amount of learning potential is relatively low. Seeking a high-flyer starts the relationship off with a set of unhealthy expectations. Moreover, the high-flyer may be too preoccupied with his or her own career to give much time to someone else.

-

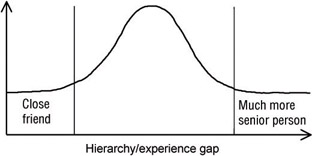

Avoid too great a hierarchy or experience gap between mentor and mentee. Figure 9 illustrates the point.

Figure 9: The hierarchy/experience gap between mentor and menteeIf the experience gap is too narrow, mentor and mentee will have little to talk about. If it is too great, the mentor's experience will be increasingly irrelevant to the mentee. Whereas once upon a time we could broadly say that there should not be more than two layers of hierarchy between mentor and mentee, organisation structures are now so complex and a single layer of management may hide such a wide variation in status, experience and ability that such a simple rule no longer suffices. It is up to the mentee and the programmeco-ordinator to establish an appropriate learning distance.

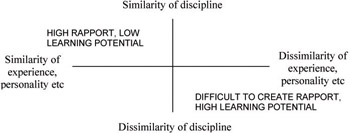

An extension of the same principle is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: How experience and discipline affect rapport and learning potentialIn the top right corner, the relatively immature learner or the person lacking confidence will often feel more comfortable with someone who shares a similar functional background and perhaps common interests and views outside of work. At the other extreme, a highly self-confident, mature learner may welcome the challenge of learning with someone with whom they have very little in common. (A classic case here is the CEO of a local authority whose mentor is a highly educated Indian pharmacist in the same borough. The CEO uses the mentor as a sounding-board on issues that affect the sizeable local ethnic community; the pharmacist has a passionate interest in politics, although only as a passive observer. ) Other people may select a mentor who is different enough to give the relationship some learning ‘bite' but similar enough to make it easy to build and maintain rapport.

Although this approach seems rather mechanical, it does seem to be how well-informed HR professionals make their instinctive choices about who they should recommend to pair. It also helps in decisions about how close the mentor should be to the mentee in organisation terms. In many modern programmes, the mentor's different perspective is a critical element of the relationship. At a large UK retailer, for example, mentees in the finance division were divided into two groups: those who needed to become more effective in their functional responsibilities, for whom a mentor from finance was provided, and those who were technically proficient but who needed greater commercial awareness, who were given mentors from sales, merchandising and marketing.

-

Avoid entanglements between line and off-line relationships.

Most companies with mentoring programmes aimed at managers, for example, prefer to establish the relationship outside the normal working hierarchy. One reason for this is that there are times in the mentoring relationship when both sides need to back off. This is something much easier to do if there is a certain distance between them, either in hierarchical level or departmental function, or both. In addition, the boss-subordinate relationship, with all its entanglements of decisions on pay rises, disciplinary responsibilities and performance appraisal, may work against the openness and candour of the true mentoring relationship. The line manager may also not have a sufficiently wide experience of other job opportunities. Moreover, unless the line manager mentors all his or her direct reports - which would involve a very substantial time commitment - there is likely to be resentment from those people who are not mentored, while those who are become cast as favourites. This does not help build team unity!

-

Ensure that mentors are committed to the programme.

A manager who is outstanding in his or her field may at first glance seem to be an ideal candidate for a mentor. It is just this sort of flair and expertise the company needs to pass on. However, if this manager's communication skills are extremely poor, or the manager resents being taken from his or her work because of mentorship obligations, he or she is unlikely to function well in the role. The company, the mentor and the mentee may all suffer in these circumstances.

Such a situation arose in one company where the programme co-ordinators attempted to assign mentors to mentees instead of allowing them to volunteer. They picked the most talented employee in research, who reluctantly agreed to act as a mentor. However, the mentee found that his mentor was usually inaccessible and rarely spent time with him. The programme co-ordinators were reluctant to assign the mentee to another person for fear of offending his mentor. Trapped by the company politics, the mentee felt his career was being sacrificed to cover up the mistakes of senior management. Not surprisingly, he left to seek his career development elsewhere.

The moral of this story is clear. Companies should choose mentors who not only can communicate their skills well but who are also actively committed to the programme. Every volunteer mentor is worth a dozen press-ganged ones. It is not necessary for the mentor to dazzle the mentee with superior knowledge and experience - he or she merely has to be able to encourage the mentee by sharing his or her own enthusiasm for the job. The mentor must be ready to invest time and effort in the relationship, so his or her interests will probably already lie in the areas of communication and interpersonal skills. The mentor must be ready to extend friendship to the mentee and be willing to let the relationship extend beyond the normal limits of a business relationship. The mentor should not participate in the programme unless he or she is willing to consider the relationship as a relatively long-term commitment.

-

Allow for a ‘no-fault divorce clause'.

It is standard good practice now for mentors and mentees to be required to review the progress of the relationship after two or three meetings, with a view to assessing how suited they are to each other. If the conclusion is that they are not, the mentor can help the mentee think through what sort of mentor - if any - he or she needs at this time. We now have a small number of cases of relationships that have been dissolved in such a process but that have subsequently resumed - perhaps years later - when the mentee's circumstances and needs have changed.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 124