Choosing Mentors

In theory, at least, the mentee should be the starting point for selecting the mentor. In practice, some organisations have begun by creating a pool of mentors and gone looking for suitable mentees for them (or sent them off to find their own!). This has the disadvantage of creating some level of obligation to find a mentee for any would-be mentor, no matter how incompetent he or she may be in the role, and risks making the whole process mentor-driven.

Every manager's job should entail a significant amount of developing other people, and indeed some companies make it a virtual condition of each manager's advancement. In practice, however, some people are better cut out for it than others. Moreover, the ability to act as a mentor will often vary according to the manager's own stage of career development. For example, someone seeking or undergoing a major change in his or her own career development may not have the mental energy to spare for someone else's issues.

In selecting the mentor, a company must have a clear sense of the qualities that make a good developer of other people's potential. These qualities may differ from company to company, even from division to division. Equally, the ideal mentor for one person may be a disaster for another. It follows, naturally, that companies will disagree on the criteria they use to identify good mentors. Gerald O'Callaghan, formerly responsible for BP Chemicals' mentoring scheme, states:

Mentors are not picked for any superhuman qualities - though some may fall into that category. Most are experienced, well-balanced professionals and managers who are interested in developing young people and broadening their own contribution to the company. They are among the best staff we have.

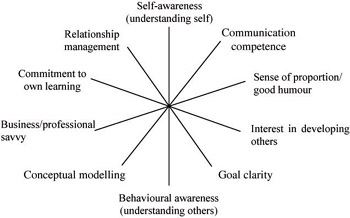

There have been numerous attempts to define the competencies of a mentor, most of them flawed by a failure to define to begin with what role is being measured. There is also a great deal of confusion in the literature between practical skills or competencies (what mentors do/how they do it) and functions/outcomes (the results of the mentoring relationship). My own view of the skill set has evolved significantly over the years and is now most succinctly summarised in Figure 7.

Figure 7: The 10 mentor competencies

[The following section on the 10 mentor competencies is taken from Clutterbuck (2000a) and is reproduced with kind permission of the publishers, the Association for Management Education and Development. ]

1 Self-awareness (understanding self)

Mentors need high self-awareness in order to recognise and manage their own behaviours within the helping relationship and to use empathy appropriately. The activist, task-focused manager often has relatively little insight into these areas - indeed, he or she may actively avoid reflection on such issues, depicting them as ‘soft' and of low priority. Such attitudes and learned behaviours may be difficult to break.

Providing managers with psychometric tests and other forms of insight-developing questionnaire can be useful if they are open to insights in those areas. However, it is easy to dismiss such feedback, even when it also comes from external sources, such as working colleagues.

Some managers actively seek psychometric analysis, yet fail to internalise it - to carry out the inner dialogue essential to carrying knowledge through to action. Not that all personality insights should necessarily lead to action; in many cases, the role of internal dialogue may be to help the person accept that a behaviour pattern or perceived weakness can reasonably be lived with.

Interviews with mentors and mentees indicate that having some level of personality and motivational insight is useful for building rapport in the early stages of a relationship. ‘This is me/this is you' - is a good starting-point for open behaviours. People who have low self-awareness can be helped in a number of ways. One is through dialogue with a trained counsellor/facilitator, helping them relate psychometric and other behavioural feedback to specific actions and behaviours. By learning how to think through such issues for themselves, they may become more effective at doing the same for others.

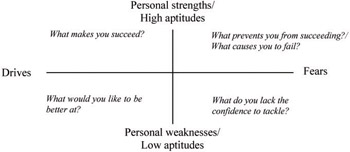

Figure 8 shows a useful way of looking at this kind of approach to building self-awareness.

Figure 8: Building self-awareness

If nothing else, the model helps open up some of the hidden boxes in the Johari window! An important debate here is whether low self-awareness is the result of low motivation to explore the inner self (disinterest), or high motivation to avoid such exploration, or simply an inability to make complex emotional and rational connections (in which case there may be physiological aspects to consider as well). The approach in helping someone develop self-awareness will be different in each case and is likely to be least effective in bringing about personal change.

2 Behavioural awareness (understanding others)

Like self-awareness, understanding how others behave and why they do so is a classic component of emotional intelligence. To help others manage their relationships, the mentor must have reasonably good insight into patterns of behaviour between individuals and groups of people. Predicting the consequences of specific behaviours or courses of action is one of the many practical applications of this insight.

Developing clearer insight into the behaviours of others comes from frequent observation and reflection. Supervision groups can help the mentor recognise common patterns of behaviour by creating opportunities for rigorous analysis.

3 Business or professional savvy

There is not a great deal to be done here in the short term - there are very few shortcuts to experience and judgement. However, the facilitator can help the potential mentor understand the need for developing judgement and plan how to acquire relevant experience.

Again, the art of purposeful reflection is a valuable support in building this competence. By reviewing the learning from a variety of experiences, the manager widens his or her range of templates and develops a sense of patterns in events. The more frequently he or she is able to combine stretching experience with focused reflection - either internally or in a dialogue with others - the more substantial and rapid the acquisition of judgement.

A useful method of helping people develop business savvy is to create learning sets, where a skilled facilitator encourages people to share their experience and look for patterns.

4 Sense of proportion/good humour

Is good humour a competence? I would argue strongly that it is. Laughter, used appropriately, is invaluable in developing rapport, in helping people to see matters from a different perspective, in releasing emotional tension. It is also important that mentor and mentee should enjoy the sessions they have together. Enthusiasm is far more closely associated with learning than boredom is!

Can adults develop a good sense of humour if they do not already have one? Probably not easily. However, a good deal of pessimistic attitude and cynicism derive from a feeling of disempowerment and a perceived lack of control over one's circumstances. Such attitude changes can be created by helping people become more at ease with themselves, with their role in the organisation and their potential to influence their environment. The most obvious way to make that happen - apart from wholesale culture change within the organisation - is for the individual to have his or her own mentor.

In practice, good humour is a vehicle for achieving a sense of proportion - a broader perspective that places the organisation's goals and culture in the wider social and business context. People acquire this kind of perspective by ensuring that they balance their day-to-day involvement with work tasks against a portfolio of other interests. Some of these may be related to work - for example, developing a broader strategic understanding of how the business sector is evolving. Others are unrelated to work and may encompass science, philosophy or any other intellectually stimulating endeavour. In general, the broader the scope of knowledge and experience the mentor can apply, the better sense of proportion he or she can bring.

5 Communication competence

Communication is not a single skill: it is a combination of a number of skills. Those most important for the mentor include:

-

listening - opening the mind to what the other person is saying, demonstrating interest/attention, encouraging him or her to speak, holding back on filling the silences

-

observing as receiver - being open to the visual and other non-verbal signals, recognising what is not said

-

parallel processing - analysing what the other person is saying, reflecting on it, preparing responses; effective communicators do all of these in parallel, slowing down the dialogue as needed to ensure that they do not overemphasise preparing responses at the expense of analysis and reflection; equally, they avoid becoming so mired in their internal thoughts that they respond inadequately or too slowly

-

projecting - crafting words and their emotional ‘wrapping' in a manner appropriate for the situation and the recipient(s)

-

observing as projector - being open to the visual and other non-verbal signals, as clues to what the recipient is hearing/understanding; adapting tone, volume, pace and language appropriately

-

exiting - concluding a dialogue or segment of dialogue with clarity and alignment of understanding (ensuring that the message has been received in both directions).

Some tools to help develop these competencies are neurolinguistic programming (if used with a sense of proportion) and situational communication.

Situational communication, developed by the item Group with help from Birkbeck College, helps people understand the communication requirements of different commonplace situations and focus on the development of specific skills in those situations. It thus has a very high utility factor. Alongside situational communication is a very practical method of diagnosing communication styles, which enables the individual to become more self-aware of his or her own style preferences and to recognise the preferences of others. Good mentors will generally need a strong sense of situation and a high degree of adaptability between styles.

6 Conceptual modelling

Effective mentors have a portfolio of models they can draw upon to help mentees understand the issues they face. These models can be self-generated (eg the result of personal experience), drawn from elsewhere (eg models of company structure, interpersonal behaviours, strategic planning, career planning) or - at the highest level of competence - generated on the spot as an immediate response.

According to the situation and the learning styles of the mentee, it may be appropriate to present these models in verbal or visual form. Or the mentor may not present them at all - simply use them as the framework for asking penetrating questions.

Developing the skills of conceptual modelling takes time, once again. It requires a lot of reading, often beyond the normal range of materials that cross the individual's desk. Training in presentation skills and how to design simple diagrams can also help. But the most effective way can be for the mentor to seize every opportunity to explain complex ideas in a variety of ways, experimenting to see what works with different audiences. Eventually, there develops an intuitive, instinctive understanding of how best to put across a new idea.

7 Commitment to one's own continued learning

Effective mentors become role models for self-managed learning. They seize opportunities to experiment and take part in new experiences. They read widely and are reasonably efficient at setting and following personal development plans. They actively seek and use behavioural feedback from others.

These skills can be developed with practice. Again, having a role model to follow for themselves is a good starting-point.

8 Strong interest in developing others

Effective mentors have an innate interest in achieving through others and in helping others recognise and achieve their potential. This instinctive response is important in establishing and maintaining rapport and in enthusing the mentee, building confidence in what he or she could become.

While it is possible to ‘switch on' someone to the self-advantage of helping others, it is probably not feasible to stimulate an altruistic response.

9 Building and maintaining rapport/relationship management

The skills of rapport-building are difficult to define. When asked to describe rapport in their experience, managers' observations can be distilled into five characteristics:

-

trust - Will they do what they say? Will they keep confidences?

-

focus - Are they concentrating on me? Are they listening without judging?

-

empathy - Do they have goodwill towards me? Do they try to understand my feelings, and viewpoints?

-

congruence - Do they acknowledge and accept my goals?

-

empowerment - Is their help aimed at helping me stand on my own feet as soon as is practical?

To a considerable extent, the skills of building and maintaining rapport are contained in the other competencies already described. However, additional help in developing rapport- building skills may be provided through situational analysis - creating opportunities for the individual to explore with other people how and why he or she feels comfortable and uncomfortable with them in various circumstances. This kind of self-knowledge can be invaluable in developing more sensitive responses to other people's needs and emotions.

The mentor can also be encouraged to think about the contextual factors in creating rapport. Avoiding meeting on the mentor's home ground (eg in his or her office) may be an obvious matter, but where would the mentee feel most comfortable? Sensitivity to how the meeting environment affects the mentoring dialogue can be developed simply by talking the issues through, both in formal or informal training and with the mentee.

10 Goal clarity

The mentor must be able to help the mentee sort out what he or she wants to achieve and why. This is quite hard to do if you do not have the skills to set and pursue clear goals of your own.

Goal clarity appears to derive from a mixture of skills including systematic analysis and decisiveness. Like so many of the other mentoring competencies, it may best be developed through opportunities to reflect and to practise.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 124