Trust as a Three Party Relationship

|

One might object that we overstate the importance of trust in social actions such as contracting, and organisations. In fact, it might be argued that people put contracts in place precisely because they do not trust the agents they delegate tasks to. Since there is no trust, people want to be protected by the contract. The key in these cases would not be trust, but the ability of some authority to assess contract violations and to punish the violators. Analogously, in organisations people would not rely on trust but on authorisation, permission, obligations and so forth.

This view is correct only if one adopts a quite limited view of trust in terms of beliefs relative to the character or friendliness, etc., of the trustee (delegated agent). In our view, in those cases (contracts, organisations) we just deal with a more complex and a specific kind of trust. But trust is always crucial.

We put a contract in place only because we believe that the agent will not violate the contract, and this is precisely "trust." We base this trust in the contractor (the belief that she or he will do what promised) either on the belief that she or he is a moral person and keeps her or his promises, or on the belief that she or he worries about law and punishment.

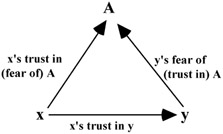

To be more clear, this level of trust is a three party relationship: it is a relation between a client X, a contractor Y and the authority A. And there are three trust sub-relations in it (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Trust as a Three Party Relationship

Trust(X, Y, τ); Trust(X, A, τ'); and Trust(Y, A, τ'); where τ is the task that Y must perform for X; τ' the task that A must perform for X towards Y, i.e., check, supervision, guarantee, punishment, etc. (Of course, Y's trust about τ' is strange, since τ' is a danger for him — see later). More precisely and importantly in X' s mind, there is a belief and a goal (thus an expectation) about this trust of Y in A:

BX(Trust(Y, A, τ')) AND GoalX(Trust(Y, A, τ')).

And this expectation is the new level of X's trust in the contractor.

X trusts Y by believing that Y will do what promised because of her/his honesty or because of her/his respect/fear toward A. In other words, X relies on a form of paradoxical trust of Y in A: X believes that Y believes that A is able to control, to punish, etc.

Of course, normally a contract is bilateral and symmetric, thus the point of view that Y should be added, and his trust in X and in A as for monitoring X.

Notice that Y's beliefs about A are precisely Y's trust in the authority when she or he is the client, while, when Y is the contractor, the same beliefs are the bases of her or his respect/fear toward A.

Positive Trust vs. Aversive Trust: The Common Core of Trust and Fear

There is a paradoxical, but effective form of trust, which is trust in threats and threatening agents: fear as a form of trust. The basic core of the two attitudes is in fact the same. This is important since what in a given circumstance appears as worry and fear produces in another circumstance a normal trust. As we have just said, in a contract X trusts Y because X trusts the authority's capacity of punishing Y in case of violation, and because X trusts Y's fear of authority and punishments. But Y's fear of authority is precisely his trust in authority as able to check and punish X (and vice-versa): the same evaluations of the authority are at the same time trust in it and wonderment/ awe/fear depending on the point of view.

In other words, fear and trust share a common conceptual core that we already identified:

(BX(PracPossY(α,g))) AND (BX(IntendY(α,g) AND PersistY(α,g))).

We presented them as the two basic beliefs of (positive) trust (Cfr. fig 1), but this in fact only depends on X's goal: if X has the goal g:

(GoalXg).

We have a positive expectation (Castelfranchi, 1997) and then (positive) Trust. On the contrary, if X does not want what she expects:

(GoalX g).

We have negative expectation and aversive "trust."

In this case, for X, Y' s power of doing α is a threat, is a negative power, and Y' s propensity (for example, intention and persistence) to do α is bad-will.

The presence of the positive goal makes the two beliefs the core of "reliability" and Trust; the presence of the negative goal makes them the core of Y's fears.

Reliability and trust is what makes effective promises (in fact, what is promised is a goal of X). Fear is what makes threats effective (since what is threatened is the opposite of a goal of X). When we say, "it promises to rain" or "it threatens to rain" our beliefs are the same, only our goal (and then our attitude) changes: in the first case we want rain, in the second we dislike it.

In sum, in contract and organisation it is true that "personal" trust in Y may not be enough, but what we put in place is a higher level of trust, which is our trust in authority but also our trust in Y as for acknowledging, worrying about and respecting the authority. Without this trust in Y, the contract would be useless. This is even more obvious if we think of possible alternative partners in contracts: how to choose among different contractors under the same conditions? The choice is made precisely on the basis of our degree of trust in each of them (trust about their reliability in respecting the contract).

As we said these more complex kinds of trust are just more rich specifications of the reasons for Y doing what we expect: reasons for Y' s predictability, which is based on her or his willingness (Intend); and reasons for her or his willingness (she or he will do α, either because of her or his selfish interest, or because of her or his friendliness, or because of her or his honesty, or because of her or his fear of punishment: several different bases of trust).

Increasing Trust: From Intentions to Contracts

What we have just described are not only different kinds and different bases of trust. They can be conceived also as different levels/degrees of social trust and additional supports for trust. We mean that one basis does not necessary eliminate the other, but can supplement it or replace it when is not sufficient. If I do not trust enough in your personal persistence, I can trust in you to keep your promises and if this is not enough (or is not there), I can trust in you to respect the laws or, at least, to worry about being punished if you don't.

We consider these "motivations" and these "commitments" not all equivalent: some are stronger or more cogent than others (Castelfranchi, 1995).

This more cogent and normative nature of S-Commitment explains why abandoning a Joint Intention or plan, a coalition or a team is not so simple as dropping a private Intention. This is not because the dropping agent must inform her partners — behaviour that sometimes is even irrational — but precisely because Joint Intentions, team work, coalitions (and what we will call Collective-Commitments) imply S-Commitments among the members and between the member and her group. In fact, one cannot exit a S-Commitment in the same way one can exit an I-Commitment. Consequences (and thus utilities taken into account in the decision) are quite different because in exiting S-Commitments one violates obligations, frustrates expectations and rights she created. We could not trust in teams and coalitions and cooperate with each others if the stability of reciprocal and collective Commitments was just like the stability of I-Commitments (Intentions).

Let us analyze more carefully this point, by comparing five scenarios of delegation:

Intention Ascription

X is weakly delegating Y a task τ (let's say to raise his arm and stop the bus) on the basis just on the hypothetical ascription to Y of an intention (he intends to stop the bus in order to take the bus).

There are two problems in this kind of situation:

-

the ascription of the intention is just based on abduction and defeasable inferences, and to rely on this is quite risky (we can do this when the situation is very clear and very constrained by a script, like at the bus stop);

-

this is just a private intention and a personal commitment to a given action; Y can change his private mind as he likes; he has no social binds in doing this.

Intention Declaration

X is weakly delegating Y a task τ (to raise his arm and stop the bus) on the basis not only of Y' s situation and behaviour (the current script) but also or just on the basis of a declaration of intention by Y. In this case both the previous problems are a bit better:

-

the ascription of the intention is more safe and reliable (excluding deception that on the other side would introduce normative aspects that we reserve for more advanced scenarios);

-

now Y knows that X knows about his intention and about his declaring his intention; there is no promise and no social commitment to X, but at least in changing his mind Y should care about X's evaluation of his coherence or sincerity or fickleness; thus he will a bit more bound to his declared intention, and X can rely a bit more safely on it.

In other terms, X's degree of trust can increase because of:

-

either a larger number of evidences;

-

or a larger number of motives and reasons for Y doing τ;

-

or the stronger value of the involved goals/motives of Y.

Promises

Promises are stronger than a simple declaration or knowledge of the intention of another agent. Promises create what we called a Social-Commitment, which is a rights-producing act, and determine rights for X and duties/ obligations for Y. We claim that this is independent on laws, authority, punishment. It is just at the micro level, as inter-personal, direct relation (not mediated by a third party, be it a group, an authority, etc.).

The very act of committing oneself to someone else is a "rights-producing" act: before the S-Commitment, before the "promise," y has no rights over x, y is not entitled (by x) to exact this action. After the S-Commitment, there exists a new and crucial social relation: y has some rights on x, she is entitled by the very act of Commitment on x's part. So, the notion of S-Commitment is well defined only if it implies these other relations:

-

y is entitled (to control, to exact/require, to complain/protest);

-

x is in debt to y;

-

x acknowledges to be in debt to y and y's rights.

In other terms, x cannot protest (or better he is committed to not protesting) if y protests (exacts, etc.).

One should introduce a relation of "entitlement" between x and y, meaning that y has the rights of controlling α, of exacting α, of protesting (and punishing), in other words, x is S-Committed to y to not oppose to these rights of y (in such a way, x "acknowledges" these rights of y) (Castelfranchi, 1995).

If Y changes his mind, he is disappointing X's entitled expectations and frustrating X's rights. He must expect and undergo X's disappointment, hostility and protests. He is probably violating shared values (since he agreed about X's expectations and rights) and then is exposed to internal bad feelings, such as shame and guilt. Probably he does not like all this. This means that there are additional goals/motives that create incentives for persisting in the intention. X can reasonably have more trust.

Notice that also the declaration is more constraining in promises: to lie is more heavy.

Promises with Witness and Oaths

Even stronger is a promise in front of a witness, or an oath (which is in front of God). In fact, there are additional bad consequences in case of violation. Y would jeopardise his reputation (with very bad potential consequences) (Castelfranchi et al., 1997), receiving a bad evaluation also from the witness; or be bad in front of God and eliciting his punishment.

Thus if I do not trust what you say, I will ask you to promise this; and if I do not trust your promise I ask you to promise in front of other people or to make an oath about this. If I worry that you might negate that you promise, I will ask for it in writing and ask you to sign something, and so on.

Contracts

Even public promises might not be enough and we may proceed in adding binds to binds in order to make Y more predictable and more reliable. In particular, we might exploit more the third party. We can have a group (Singh, 1999), an authority able to issue norms (defending rights and creating obligations), to control violation, to punish violators. Of course this authority or reference group must be shared and acknowledged, and as we said, trusted by both X and Y. Thus, we have an additional problem of trust. However, now Y has additional reasons for keeping its commitment and X's degree of trust is higher.

Notice that all these additional beliefs about Y are specific kinds or facets of trust in Y: X trusts that Y is respectful of norms, or that Y fears punishments; X trusts in Y's honesty or shame or ambition of good reputation, etc.

A bit more precisely: the stronger Y's motive for doing τ and then the stronger his commitment to τ; the larger the number of those motives; and the stronger X's beliefs about this; the stronger will be X's trust in Y as for doing τ.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143