8.2 Case narrative

Gowing Information Services (GIS, a pseudonym) are a software house and a part of the large Cass group of companies. Cass (also a pseudonym) are one of the top 250 companies in the UK Financial Times Stock Exchange companies with an aggressive , entrepreneurial style. Gowing was founded in 1995 as a series of software product acquisitions. In 1998, they employed approximately 100 employees and their turnover was around & pound ;10 million which made a contribution of around 10 per cent of the group profitability. Although part of the Cass group, Gowing are run independently.

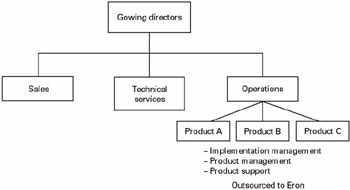

Figure 8.1 shows the Gowing organization chart at the start of the research in 1998. Eron (also a pseudonym) is an Indian software outsourcing company with a ˜software factory located in Chennai. It was established in the early 1980s and is one of the top 30 software companies listed on the Indian Stock Exchange. Eron has a centre in the UK and in 1998 turnover was around 15 million across the group. It employed around 120 staff in the UK operations. Eron had grown largely as a result of the strategic initiatives of the visionary Indian directors of the firm and was serving markets in the UK, the USA and Japan. It had an ambitious expansion strategy to include other countries in its future marketing efforts.

Figure 8.1: Gowing: organization chart

While the Gowing management had no previous experience of GSA, some aspects of Cass portfolio of businesses included outsourcing of various business functions. In that sense, Gowing s initiative in India was not totally without experience. The operations functions comprising implementation management, product management and product support functions were outsourced to Eron. In the early stages, this work was done with existing staff from corporate acquisitions but was eventually taken over completely by Eron and part of the work outsourced to India. Gowing serves the UK public sector with specialist accounting software that is based around relational database technology often linking into large mainframe computers for bulk processing. As will be discussed later, Gowing was formed from a series of corporate acquisitions and part of a group of companies. Cass perceived Gowing as part of a portfolio of companies it owned. The most important priority for Gowing, expressed by Cass directors, was making profits and shareholder satisfaction. Cass directors thus perceived Gowing as a ˜money-making machine .

Initiation (1995 “1996)

In 1993, the Cass group embarked on an acquisition strategy and made an offer to acquire a specialist software business called RDC Ltd, as it supplied a market already served by Cass but not with software. The following year, David Jones joined Cass and subsequently acquired the rights to a product from PJ Computing Ltd for similar reasons. That same year Jones was made Managing Director of the new firm, now named Gowing Information Services and remained until 1999 when he was promoted within Cass. Later in 1994, in a similar acquisitive move, Jones with backing from Cass acquired a small company, Hellenic Ltd, which had a product that complemented their existing portfolio. These acquisitions were important as they came with new products and some of the staff who had originally developed them as well, as in the case of RDC Ltd. Thus, the Gowing product portfolio consisted of three software products and the staff from PJ Ltd (shown as product A in figure 8.1, p. 161), RDC (product B), and Hellenic Ltd (product C) which were a result of three acquisitions making up the embryonic Gowing company.

The software products at Gowing comprised complementary accounting and financial reporting systems that were marketed to a range of large British public corporations. The corporations using these products had similar needs but sometimes customization was needed to take account of slight variations in the accounting conventions of regional offices. From its inception, the Gowing product portfolio was under constant change owing to revisions required by external bodies, involving legislative requirements on taxation , for instance. Other development work included maintenance operations and major updates, for example, from a menu-driven to a graphical user interface.

Gowing s office was located in RDC s buildings in a Devon seaside town. From the perspective of software- related staff, this was not a good location. Many highly skilled software staff were not willing to live and work in the area. They perceived the town to be in decline, inconveniently located, with few urban attractions such as cinemas, restaurants , etc. Interviews with several members of the staff indicated that their perception of the geographical area was a problem: ˜There is very little to do here in the evenings and weekends: it is dead, and: ˜It is like dole-on-sea: there are many unemployed.

Gowing is the only major software company in the local area and thus workers with relevant skills are not close at hand. The lack of any international population and associated networks also makes it difficult to attract foreigners. At the time of the GSA decision, there was a shortage of computer software skills generally in the UK, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to attract and retain staff. Existing staff was keen to move to city locations with higher salaries and better promotion prospects.

With this context in mind, David Jones, the Managing Director of Gowing, initiated the outsourcing of software development in November 1995. His stated motivation for outsourcing was primarily a resource issue, the desire to ˜tap into the large Indian software manpower pool. It was perceived that outsourcing to India could provide a logistical advantage in that people could be found at short notice as well as with a high level of English literacy and a large number of Indian computer science graduates could be hired at relatively lower costs than in the UK. According to Gowing s figures, UK programmers tended to cost on average 30 per cent more than Indian programmers. An important factor for Gowing management was the need to form an organizational culture , as the company was made up of a series of corporate acquisitions: the three companies had very different ways of operating. Gowing management perceived RDC as having had the strongest culture as it had been owned by the public sector and had what was perceived as a ˜public sector approach to software development. RDC s social relations and dress were informal and a ˜kind of brotherhood existed between the 25 ex-RDC actors. Work was consequently completed as a result of favour trading and goodwill, systems were often lacking in complete documentation and project planning was informal, overall documentation was considered of less importance than trust and completed releases of software.

The PJ product (A) was developed by a small youthful software house and was acquired along with the services of three contract programmers. Hellenic s product (C) also came with three staff. The staff from these two organizations were not used to extensive documentation of systems and detailed project planning. David Jones told us that: ˜Staff who came with these different acquisitions had very different views of organizational life and of how software development should take place.

Gowing management told us they wanted to form a homogeneous disciplined approach to software development work with an emphasis on efficiency and quality. This factor was another key motivation for outsourcing to India with Eron: it was perceived that Eron s emphasis on structured methodologies and disciplined quality management approach might help to tighten procedures at Gowing. A mutual friend of Jones and the Eron UK manager introduced the two companies and this led to initial meetings followed by a decision to ˜body-shop a small number of Eron staff into the UK. For Gowing, this move to body-shopping and involving the Indian programmers was a low-risk strategy to understand the possibilities of outsourcing and the extent to which Eron s disciplined approach could work in practice. Gowing management were optimistic at this point that a solution to their skills problems might be in sight.

The outsourcing activity began with four Indian Eron programmers on-site at Gowing s Devon offices. They were to assist with product development workload in product A (the ex-PJ Ltd computing product). Initially, this work involved mainly continued maintenance operations, which was a small project relative to the other products. Product A was seen as vulnerable as it was staffed by contract programmers who were expensive and could leave at any time. At Gowing, Eron staff introduced their quality methodology. It was a traditional ˜life-cycle -style methodology consistent with ISO 9000 accreditation requirements and prescriptions of structured, disciplined approaches to development and project management.

During this time, the Eron programmers were used in a ˜body-shopping role. They supplemented the work of UK staff involved in routine development and maintenance operations of the financial applications that were built on an Oracle database platform. Eron staff had to fully understand the application, their understanding was judged informally, at first based on their working on the development for a period of time and later by a written test and the application of set criteria.

Growth phase (1996 “1998) and maturity (post-1998)

Over time, Gowing management gradually increased its trust in the competence and capability of Eron programmers. In this case trust was primarily gained by the application of an abstract system, a disciplined methodological approach to development as well as the adherence to procedures that the Gowing management perceived to be characteristic of the Indian Eron programmers. As a direct consequence of this, it was decided by Gowing management that a senior Indian Eron project manager would be moved from Chennai to Devon and the Eron staff would take over the Gowing product A development. Staff originally from PJ Ltd had drifted to other companies by this time and Eron Indian programmers were useful in filling the gap. After this, the model of work changed to an offshore model in which some staff and work were moved to Chennai. At this stage, roughly two- thirds of the Eron team (five staff members) were situated in India. Low-level specifications of work to be coded for the Oracle-based accounting product were sent by the Eron staff in Britain to the Chennai-based team who would return the code for testing. To facilitate communication and the passage of specifications and code, a leased line was in place between Eron s Chennai software factory and Gowing s offices in Britain. Email and telephone were used to clarify any issues or misunderstandings between the Indian team split between Britain and India.

As the Indian programmers had showed competence in the development of product A, it was decided by Gowing management that the Eron methods and employees were to be subsequently ˜rolled into Gowing product B which had been staffed by ex-RDC programmers. The implication of this was that the RDC staff would be required to use Eron quality methods under the supervision of the Eron project manager and comply with the standards imposed by the methodology. These standards were in the form of project management documentation of the adherence to deadlines and milestones. Other standards included rigid adherence to the detailed specifications, outputs and other documents of the various phases of the life-cycle-style methodology.

At this stage, the control objective of Gowing management was reflected in Jones management style, described by some interviewees as ˜ ruthless and ˜mercenary . His actions were legitimated by the Cass strategy of acquisition and profit making. The informal culture of RDC clashed with Eron s highly disciplined, transparent approach, ultimately leading to the demise of the RDC sub-culture. The ex-RDC programming staff ultimately resigned and there was a complete adoption of the Eron methodology and staff for all development work in Gowing. A period of intense development took place until the products were seen to be well understood and robust by all the staff. Eron staff now wholly develop all three products, both onshore and offshore.

Since the initial upheaval , leading to outsourcing and reorganization, the Eron “ Gowing GSA relationship has become closer, moving from a ˜body-shopping model to one where considerable responsibility has been handed to Eron staff for all development work. This has included higher-value activities even at a strategy level as well as the full range of activities in systems development including requirements capture, design, development and maintenance. The two companies have intermeshed their activities, leading to a relatively mature arrangement. They have, however, continued to experiment with different levels of onshore “offshore development. These experiments involved attempts to move offshore more than the considered optimum of two-thirds; this caused problems as reducing the number of staff onshore in the helpdesk function led to intolerable pressure and workload on the onshore staff as well as problems of delays for fault rectification owing to the India “UK time difference.

Following the beginning of outsourcing, Eron was able to move up the ˜trust curve as it was perceived as performing well in the ˜body-shopping activities and as a result had been given responsibility for two major products. A new contractual relationship was initiated and the outsourcing project was moved fully into a stable situation that was still current at the end of the 2000 when we visited the company again. This implied a generally accepted maturity in the relationship.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 91