Stories in Games

Stories in GamesThe use of stories in games is a fundamental part of game design. A game without a story becomes an abstract construct. Of course, for some games, such as Tetris , this is ideal, but the vast majority are much improved by the addition of a story. Over the course of the 20th century, story form and design have been researched. As always, research gravitates toward money, so the most significant portion of this research over the last few years has tended to be about Hollywood and the movie industry. The rewards for a hit movie are usually much greater than the equivalent rewards for a best-selling book, so this is where we find the most accessible information. The main focus of story-form research has been based on the concept of the monomyth : the fundamental story form that is common to most, if not all, accomplished literature and movies. We'll be discussing the structure of the monomyth a bit later. Of course, we are not saying that all stories conform to this formulaic approach. Many do, but not all. What we can say is that the concepts and ideas behind the monomyth are present in some form in virtually all nontrivial stories. Previously, we mentioned the story spectrum as applied to games. At one end of the spectrum, we have the light backstory usually a brief sentence or paragraph that sets the theme for a game. This is usually fairly trivial stuff, so we will not concern ourselves with it much. However, toward the other end of the spectrum, the importance of the story increases , culminating in those games in which the story is the game. In these cases, you will find the recurring elements of the monomyth, and it is in these cases that the structure and definition of the story is most important. Hence, it is this area that we will focus on. Don't worry, though: All the concepts we discuss are equally applicable to the lighter end of the story spectrum. It's just that they are not as important for the success (or failure) of the game. If a game has a bad backstory, and the backstory has little impact on the game, then no one is really going to care. In fact, a number of games pride themselves on the absurdity of their (either real or implied ) backstory. Consider Sega's Super Monkey Ball . The player's avatar is a monkey. In a ball. Collecting bananas. And as far as we can tell, that is the extent of the story, which is fine for that particular game. Any attempt to flesh it out further would be extraneous effort. Simple BackstoriesNot all games require a detailed and rigorous story. Often a couple of short paragraphs just setting the background are required. For example, a game such as R-Type doesn't need much of a story line. An evil galactic empire is invading, and you're the only one who can stop it. Original? No. Good enough for the purpose? Yes. If a game doesn't require a detailed backstory, there is nothing to be gained by adding one. Think carefully before you decide this, though; consider the difference that the addition of a story made to Half-Life . (For those of you who don't know, Half-Life was the first decent attempt at a first-person shooter with a strong backstory.) Games such as the Mario series often have simple backstories that are expanded upon during the game. The story line does not affect the gameplay to a restrictive degree, but it does provide direction and increases the interest level. By creating a loose story line that does not impact the gameplay, the designer increases the interest level by using the story line to involve the player in the plight of the characters . Commonly, the backstory is used to provide a framework for a mission-based game structure. For the majority of games, this is the ideal approach. As the complexity of the game increases, the relative importance of the story to the gameplay can (but does not have to) increase. For example, the story line of a simple arcade game is a lot less important to the gameplay than in the case of a more complex game such as a role-playing game. This is shown in Figure 4.1. Who Is the Storyteller?It is important for the designer to consider who exactly the storyteller is. Who is the main driving force behind the narrative? Is it the designer or the player? Often a game designer falls victim to "frustrated author syndrome." The designer feels as if she should be writing a great novel and forces a linear and restrictive story line onto the player. In other cases, the designer might swamp the player with reams of unnecessary dialogue or narrative. The player then has to fight his way through the excessive text, attempting to sort the wheat from the chaff. The main distinguishing factor between games and other forms of entertainment is the level of interactivity. If players just wanted a story, they could watch a movie or read a book. When players are playing a game, they do not want to be force-fed a story that limits the gameplay. Stories generally are not interactive; the amount of branching available in the story tree is limited, so only a few alternative narrative paths are usually available. Hence, the story needs to be handled carefully. It should not be forced on the player, and wherever possible, you should avoid railroading the player down limited story paths because of your own frustrated author syndrome. So what is the answer to the question of who the storyteller is? Simple. The players should be the primary storytellers. They are the stars of the show. The time they spend playing the game is their time to shine , not yours. Consequently, the game should be structured so that for the majority of the time, they are telling their own story. The theme of a story is the philosophical idea that the author is trying to express. You can think of it as the "defining question" of the work. For example, can love triumph? Is murder ever justified? Are dreams real? Is death the end? We've said that the true author of a game narrative is (or should be) the player. Game design can steer the player toward the favored themes of the designer, but it's like leading the proverbial horse to water. You cannot force the players to think your way. Bearing these caveats in mind, let us continue with a discussion of story structure. The Monomyth and the Hero's JourneyWhat is this construct that we are calling the monomyth? In 1949, Joseph Campbell published a seminal work called The Hero with a Thousand Faces , exploring the interrelationship among the legends and myths of cultures throughout the world and extracting a complex pattern that all of these stories followed. This pattern, the monomyth, is called "The Hero's Journey" and describes a series of steps and sequences that the story follows , charting the progress of the story's hero. The archetypal character typesthose that occur across all cultures and agesare incumbent features of the hero's journey. These powerful archetypes are so innately recognizable by all individuals through Jung's concept of the collective unconscious that they have a familiar resonance that serves to strengthen and validate the story. We cover these in detail in the next chapter. The following quote summarizes Campbell's belief in the universal story form.

Despite the excellence of Campbell's book, it can be somewhat heavy going, and for all but the most story- intensive games, it could be considered overkill. The Hero with a Thousand Faces is recommended as an essential addition to the game designer's reference library. For the purposes of this chapter, we want to make use of a slightly lighter analysis, one that has been updated with modern considerations and that presents the concepts in a clearer fashion. Fortunately, such a work exists. In 1993, screenwriter Christopher Vogler published the first edition of a book based on a seven-page pamphlet that he had been circulating around the Hollywood studio where he worked. This pamphlet, "A Practical Guide to the Hero's Journey," took the movie industry by storm , and the obvious step for Vogler was to expand the work and publish a book based on it. This book, The Writer's Journey , presents the concepts and ideas of the hero's journey in a concise and easily digestible form. It's not a perfect fit for our purposes, but it is an excellent start. As such, it forms the basis of our analysis of stories and comes heavily recommended. Any serious game designer needs to read this book thoroughly. Note that we are not just trying to feed you the line that games are merely interactive movies. That is plainly not true. They are an entirely different medium. However, the ideas presented by Campbell and Vogler are universal. They transcend the medium of film and are applicableat least, to some extentdirectly to the field of game design, particularly where the story line is a major factor in the design. Too Good to Be True?One of the chief arguments against patterns especially when related to design aspectsis that they stifle creativity, producing a lackluster and formulaic output. Of course, if you just take the basic interpretation and apply it, this can be true. However, it should be realized that the monomyth is a form, not a formula. It is a set of guidelines for creating a rewarding and fulfilling story line, not a cookie- cutter template for autogenerating the same tired old story in a slightly different guise. Another important point to bear in mind is that we are using the term hero to refer to either sex. It could just as easily apply to a female hero as it does to a male. With that in mind, let's take a look at this universal story form in more detail. The next few sections describe the stages present in Vogler's interpretation of the hero's journey. We will be careful to use the same terminology and notation as Vogler so that those of you who refer to his book will be able to use the same frame of reference. Note that not all games use these structures for their story line. Some use just a few of them and miss out on key features (and, in some cases, their story usually feels somewhat unsatisfactory). For others, some of the steps are inappropriate and would add nothing to the game. For example, many games gloss over the introduction to the ordinary world and the hero's refusal of the call. Sometimes that is idealthe player actually wants to be a gung-ho hero who is ready for anything, no matter how unrealistic that might be. There is no law, written or unwritten, that says that games have to conform to reality. They just have to be self-consistent. The steps in Vogler's hero's journey are as follows:

We discuss these in detail and apply the ideas to game story design in the following sections. The Ordinary WorldAll stories should start at the beginning (or thereabouts). The ordinary world is where the player first meets the hero and is introduced to her background and normal existence. The ordinary world of the hero is used to set up the story, to provide a mundane canvas for the storyteller to contrast with the special world that the hero will be entering in the game. Often the introduction to the ordinary world of the hero is combined with a prologue. The prologue generally takes one of two forms:

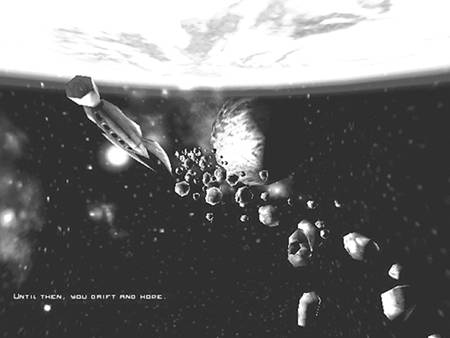

Care must be taken with the backstory and how this story is revealed to the player. Don't just blurt it out in one go. Nothing appears flatter than a straightforward monologue detailing the hero's background and motivations. It's far better to reveal the backstory gracefully. Make the player work a bit to put the pieces together. It's a more rewarding experience, and it makes the player feel as if he has achieved something in uncovering the story. Foreshadowing is a powerful technique in storytelling. Consider an example from the introduction to Valve's Half-Life . The noninteractive opening scenes tell the story of Gordon Freeman, who has accepted a research position at the ultrasecretive Black Mesa research laboratory. As Gordon takes the underground monorail to the main security entrance , he gets a glimpse of the ordinary world of the research facility. At certain points throughout the journey, Gordon's attention is drawn to various constructs and facilities that will feature heavily in the special world when the catastrophic accident occurs. Another more explicit example of foreshadowing occurs at the point at which the accident occurs. When the experiment goes awry and the dimensional rift is opened, Gordon is transported to a variety of strange locations and glimpses strange alien landscapes and beings. This (unbeknownst to Gordon) is a taste of things to come. Because foreshadowing is so powerful, it is very commonly used. Often in games that have boss characters, such as shoot 'em-ups, the boss character puts in brief cameo appearances throughout the level before appearing at the end of the level for the big confrontation. The various Star Wars games (an example of which is shown in Figure 4.3) that feature the Death Star often use this technique. The Death Star appears as part of the background graphics a couple of levels before the player is called upon to destroy it. As soon as it appears, ominously hanging in the distance like a small moon, the player knows that sooner or later he will be there. Figure 4.3. Star Wars: Rogue Squadron II. This foreshadowing is so effective because it contrasts the special world against the ordinary world. This confuses the player, and confusion eases the process of mental suggestion. Players who are susceptible to mental suggestion are easier to immerse in the game. The willing suspension of disbelief that the designer is aiming for becomes that little bit easier to achieve. The "Ordinary World" section is the place to introduce the reasoning and motivation behind the hero's being who she is. Why is she even in this situation? What is the game actually going to be about? Here we discuss the best way to get that information to the player without being blatant and uninteresting. This is where you introduce the hero to the player. You want to make the player identify with the hero. This is crucialif you fail to do this, there is no compunction to play the game. There are many ways to do this, but probably the most effective way to get the player to identify with the hero is to play on the player's emotions. We discuss nonstory-based methods of creating the bond between the player and the hero in the next chapter. For now, let's consider how you can use the story to accomplish the same task. Often in classical literature, the hero has a flaw or some mental or spiritual wound that the reader can empathize with. This doesn't necessarily mean that the hero needs to be an inmate of a mental asylum (although some games have used just that mechanism American McGee's Alice , shown in Figure 4.4, was set in the fantasies of a female patient). Figure 4.4. American McGee's Alice. An example is Gordon Freeman's inexperience in his new job. Gordon is a new employee in a top-secret lab. The player can empathize with this. We're pretty sure that the vast majority of Half-Life players would also feel rather overwhelmed in Gordon's position. The superb introductory sequence amplifies this sense of awe and transmits it to the player. In this way, a bond is created between the player and the avatar. The Call to AdventureThe call to adventure is the first inkling the hero gets that she is going to be leaving the security of the ordinary world to enter the special world of the adventure ahead. Now, bear in mind that the players already know they are going to be entering a special world, so it is very difficult to surprise them. It can be doneyou can take the story line off at a tangent they would never expectbut the safer and easier approach is to make use of this expectation and build up the players' anticipation levels so that they can hardly wait to enter the special world. Don't try to maintain this buildup for too long, however. The player bought the game to play it, not to wait until the designer allows him to play it. The call to adventure can take many forms. Infogrames's Outcast (see Figure 4.5) portrays the hero, retired Special Forces man Cutter Slade, sitting in a bar knocking back straight whiskies. As he is sitting nursing his drink, several G-men approach him and inform him that he is needed with the utmost urgency by Cutter's old commanding officer. This is his first call to adventure. Figure 4.5. Outcast. The call to adventure is often the catalyst or trigger that initiates the story line. It can take many forms, and we detail some of those here. In a few stories, the hero receives multiple calls. It then becomes the task of the hero to decide how to prioritize these callswhich to answer first or which to reject outright . In some cases, these priorities will already have been decidedor at least hinted atby the designer. Ultima VII epitomizes this concept. The avatar really leaves his own world through an obelisk into the fictional world of Brittania. In a sense, there are two dimensions to the fiction in the game because the "real world" is the initial setting of a fictional story. This extra dimension adds tremendously to the game experience, by adding yet another level to the suspension of disbelief. When playing Ultima VII , the player is fully engaged in the game world and the character. When players occasionally do think about the "real world," it is often thoughts of the avatar's "real world," not their own. They empathize with the avatar's wish to return home. In other words, they're sympathetic to the plight of a fictional game character! Often the call to adventure is personal to the hero. Nintendo uses this technique a lot, particularly in the Mario series of games. For example, usually the Princess manages to get herself captured, and Mario, being the sterling sort of hero that he is, feels a burning urge to rescue her. This is a common thread running through the entire series of games. The call to adventure often involves family or friends in jeopardy. In Luigi's Mansion , Luigi is called upon to rescue his brother, who is lost inside a mysterious haunted house. Of course, the call does not need to be on a level personal to the hero. External events are often used as a call to adventure. Some grand event happening on a large scale might act as the call. In these cases, only the hero's sense of decency (or other motivation, such as avarice) propels the hero into adventure. Temptation can always be used as a call. Many forms of temptation exist, but in games, it usually comes in the form of greed. There are various reasons for this. One is that sexual temptation does not make a very good theme for a game. A few games have tried to use this, but they were, for the most part, poor games, and in some cases, verged on the extremely distasteful, with Custer's Revenge (which can be seen with a Google search) being a particularly obnoxious (and classic) example. A far safer and more socially acceptable form of temptation is greed. (You've got to love capitalism !) For example, many games use the old "earn as much cash as possible" or " treasure hunting" paradigms as the call to adventure. Games such as Monopoly Tycoon (and, in fact, the majority of the tycoon-style games) use greed as the motivation to play. Remember, kiddies, greed is good! Even Luigi's Mansion uses treasure hunting as a secondary call (as do the majority of the other games in the series). The primary call is to rescue Mario, but the secondary call is to get rich in the process. Sometimes the call comes in the form of a message from a herald, a character archetype. The herald does not have to be an ally of the hero. In fact, the character acting as the herald might reappear as another character archetype later in the game, such as the mentor or the shadow. Examples of the use of the herald to deliver the call are present in many games. The specific example we will use here is Lionhead's Black and White . In this game, two mentor characters representing the good and evil sides of the player vie for the player's attention. Both characters call the player to adventureone on the side of good, and one on the side of evil. In other situations, the call to adventure isn't an explicit call. It can be the result of a void felt by the hero due to a lack of or a need for something. What that "something" is can be the choice of the game designer. For example, in Planescape: Torment , the call for adventure is lack of knowledge on the part of the hero. The fact that he is referred to as the Nameless One indicates the magnitude of the call. The call to adventure does not need to be optional. The hero isn't always given a choice (even if the player is: He can choose to play or not to play). In Space Invaders, the call to adventure is the need to destroy all the aliens to prevent the player's own destruction. The Refusal of the CallIn the traditional monomyth form, the next stage after the call is the refusal. This is the representation of the hero rejecting the offer to leave her comfortable ordinary world. It does not have to be portrayed as a grandiose eventoften the refusal amounts to little more than a quiet moment of personal doubt or a brief rebellious outburst on the part of the hero. For a computer game, the call is usually not refused especially if there is only one call. After all, if that were to occur, there would be no game. That is not to say that the refusal is never issued. Usually, however, it forms part of the initial background story, as is the case with Cutter Slade in Outcast . Cutter's response to the plea for assistance from the G-men is to turn away, slug back a shot of whiskey, and growl, "I'm retired." As an example of drama, this is far more involving than if he'd just leapt to attention and replied, "Yes sir, let's go." It's more believable and compelling, leaving the player wondering, "Will he or won't he?" even though we know he will. More important, it sets the stage for conflict. And conflict, as we all know, is interesting. The refusal of the call is usually reserved for games that place more of an emphasis on story. For example, a call refusal would make little sense in a simple arcade game; it can be added to the backstory for additional flavor, but in general, it would have little effect on the gameplay. Any games that offer multiple quests and subquests allow for multiple refusals. As long as the overall grand quest is attended to, the game designer can allow the hero to ignore some of the smaller quests without any serious penalty. In the case of conflicting callswhen the hero is given two or more conflicting calls simultaneously a dynamic tension automatically is created. The player has to decide which (if any) call to follow. The classic case is the choice between good and evil. In Black and White , the player is given the choice to be an evil god or a good god (and anything in between). The player's actions determine which call he has refused. In some cases, refusal of the call can be seen as a positive action. The call to adventure can be a negative thing. For example, the hero might be offered a quest that involves partaking in some form of action that would result in unpleasant consequences. In the case of a role-playing game based on the familiar Advanced Dungeons and Dragons rules, a lawful good hero might be asked to perform an activity that would conflict with his alignment, such as killing a household of innocents. If the player sees it as advantageous in the long run to maintain his alignment, it would be wise to refuse this quest. The Meeting with the MentorThe character archetype of mentor is discussed at length in the next chapter. You've already seen an example of a mentor in the previous section, when we discussed Black and White . Another example is Morte, the first character that the Nameless One encounters in Planescape: Torment. At the start of the game, Morte's main purpose is to provide the Nameless One with information about his location and situation. As the Nameless One progresses further, Morte provides further tips and helpful suggestions until he is more familiar with his surroundings. If the call to adventure is seen as the catalyst to the story, creating an impulse and motive where previously there were none, then the meeting with the mentor serves to give direction to these unleashed forces. When the hero decides to take action, it is the task of the mentor archetype to give the hero the information needed to choose which action to take. Note that the mentor does not have to be a single character. Often the mentor is a clichd wise old man, but there is no reason why this should be the case. The position of the mentor archetype can be filled by any combination of characters that give the hero information. In fact, the mentor does not even need to be a character. The hero can use past experiences, a library, a television, or any other information source. It's not important what or who fills the role of the mentor, as long as the information the hero needs is provided. Crossing the First ThresholdAfter the hero has decided to leave the ordinary world, accepted the call to adventure, and discovered what needs to be done, she still has to make that first step and commit to the adventure. Vogler refers to this as "crossing the threshold" from the safe and comfortable ordinary world into the dangerous and strange special world of the quest ahead. This step is not always optional. Sometimes the hero is thrust into the special world against her will. For example, in Planescape: Torment , the amnesiac hero wakes into the special world at the start of the game, with only a few tattered memories of the ordinary world from which he came. To enter the special world, the hero must mentally prepare, garner her courage, and perform a certain amount of symbolic loin girding to confidently enter the strange and unknown experiences ahead. Often the hero expresses misgivings, concerns, and fears but makes the crossing anyway. This is a good time to bond the player with the hero by creating a sense of concern. The threshold guardian archetype often comes into play here. This could be manifested as the hero's own misgivings, the fear of the hero's companions, a warning from the enemy who the hero seeks to defeat, or any combination of these. The opening scene of Midway's Pac-Land (shown in Figure 4.6) shows Pac-Man leaving the ordinary world of his home and setting out of a strange road full of danger and mystery. The act of leaving the house and heading off through the dangerous ghost-infested path is the crossing of the first threshold. Figure 4.6. Pac-Land. When the first threshold of adventure is crossed, there is no turning back. The next phase is entered, and the adventure into the special world truly begins. Tests, Allies, and EnemiesThe crossing of the threshold is the first test. In this phase, many more similar tests are thrown at the hero. This phase is often the longest phase of a game story and makes up the bulk of a game. In this phase, the hero ventures forth into the special world and meets many of the character archetypes on the journey. For the majority of games, the character archetypes that the player meets are either allies, shadows, or tricksters. At the left edge of the story spectrum, you would expect to meet mainly shadows. For example, in Space Invaders , the player is alone against the alien onslaughta hero surrounded by shadow. Slightly more complex games often provide allies, such as the fairies at the end of each Pac-Land level. In arcade-style gamesthose that place more emphasis on the action than the storythese are likely to be the only archetypes present. The player will go through a series of tests with successively more powerful shadows, to be given a brief respite when an ally occasionally shows up to replenish the hero's spirit and resolve. In some cases, the player might even encounter the trickster and shape-shifter archetypes in the form of false allies who turn out to be shadows after all. In a more complex game, where story is the biggest consideration, you would expect to see many more character archetypes during this phase of the game. For example, a role-playing game with a well-developed story line would be expected to use all of the major character archetypes many times over and in varying combinations. The main purpose of this phase in the story is to test and prepare the hero for the grand ordeal that lies ahead. Here, the hero is expected to learn the unfamiliar rules and customs of the special world. During this succession of increasingly difficult tests, the hero forges alliances and makes enemies. Depending on the nature of the game, the opportunities available for the hero to actually make enemies or allies could be limited or predestined, as is the case with most games; the majority of characters the hero meets are already enemies, and allies are few and far between. This is not necessarily a disadvantage an element can still add flavor to a game, even if it is noninteractive. The Approach to the Innermost CaveAfter the succession of tests, the hero approaches the innermost cave. This is the core of the story, where the hero will find the reward he seeks. Mostly, this is toward the end of the game, but in some cases, this occurs almost exactly in the middle. The difference between these two alternatives is that the firstwhere the reward is close to the end of the gamedoesn't pay too much attention to the journey back. The retrieval of the reward is the high point of the journey, and the return is assumed. This has its merits. In some cases, you would not want to force the player to retrace his steps back the way he came. The second situation, in which the reward is close to the middle of the game, pays special attention to the journey back. In this case, retrieving the reward is only half the story. Now the hero actually has to escape with the reward and return to the ordinary world in one piece. For this style of game, the journey back is well integrated into the quest and should be significantly different than the journey that brought the hero to that point. The traditional use for this story element is to help prepare the hero for the ordeal ahead. This is done by a number of means, including doing reconnaissance, gathering information, checking or purchasing equipment, or mentally preparing and girding loins for the coming tasks . The OrdealThe ordeal is the ultimate test: the fight with the nemesis. This is the culminating battle of the story. Until now, the hero might have dealt with some serious tests, but this is the real thing. The stakes are high, and the final reward is at hand. Many games follow this pattern. In fact, any game that has a succession of levels punctuated by increasingly powerful boss enemies for the player to defeat follows this pattern. Luigi's Mansion , Quake II , Half-Life , R-Type , and Diablo II are some of these. We're sure that you can add hundreds to the list. During the ordeal, you might try to cement the player's bond with the hero further. This is sometimes achieved by making it appear as if the hero is almost defeated, before fighting back from seemingly impossible odds to defeat the enemy. In the ordeal, the hero faces the ultimate shadow. Defeat means failure, final and absolute. Victory means claiming the reward and the ultimate success. However, sometimes achieving victory is possible in many ways and at many levels, not all of them immediately obvious. For example, in the case of games such as LucasArts' Jedi Knight series, it could mean deciding whether to fight the ultimate nemesis. The RewardAfter the ultimate shadow is defeated, the reward can be claimed. The reward can come in many formsand not all of them are positive. Sometimes the reward can be a negative option, something the hero would rather avoid but cannot, or simply was not, expecting. More often, however, the reward is positive, even if it might not seem that way to the player. For example, the reward in Planescape: Torment is mortality and the promise of death. Although this might not seem like much of a reward to the player, to the herowho has endured a long and painful cycle of continual death and rebirththe ability to finally die and join his lover in the peace of eternal sleep is an ideal boon. Many games end at this point. Some of these show the remaining story as a final cut scene. For other games, this is merely the beginning of the final phase. Note that nothing says that the reward has to be the same one that the hero set out for at the beginning of the story. In Half-Life , Gordon Freeman initially sets out to escape from the alien-infested laboratory. By the end of the story, the stakesand the potential reward for successare much higher. The important thing is to make sure that the reward reflects the effort expended in reaching it. Nothing falls flat more than an insignificant rewardan excellent example of this being the ending of Unreal . After fighting the alien threat and escaping the planet, the player's avatar is left drifting in space as his escape pod runs out of fuel. The assumption is that you will eventually be rescuedor not (see Figure 4.7). Figure 4.7. The ending of Unreal . The Road BackWith the reward won, the hero now has to prepare for the journey back to the ordinary world. The experience of the adventure will have changed the hero, and it might be difficult (if not impossible) to integrate her successfully back into the ordinary world. As we've said, most games do not go as far as this in their interactive storiesinstead, they leave this and the following two story elements to a final cut scene. Interplay's Fallout (shown in Figure 4.8) used this particular element to good effect. In this post-apocalyptic role-playing game, the hero was tasked with finding a replacement chip to the water processor to allow the vault-dwellers to continue living in their underground vault. The hero was sent out into the radioactive wilderness to find this chip and, after many adventures , successfully returned with the reward. Upon his return, he was not permitted to re-enter the vault. The vault elders claimed that he had been so changed by his journey that he was too dangerous to be allowed to live in the vault with the others. Hence, he was turned away from his old ordinary world. His special world became his new ordinary world. Figure 4.8. Fallout. The ResurrectionThe resurrection is the point in the story at which all outstanding plot threads are resolved. Any problems or consequences from the retrieval of the reward are (for the most part) resolved here. Does the story resolve itself? Are any questions left unanswered? Is this an oversight on the part of the designer, or are they deliberately left open for the sequel? The resurrection is the final set of tests the hero faces before being able to enjoy the hard-earned reward fully. In conventional stories, this is comparable to the last-minute plot twist: Just when you think the story is over and the hero has won, the enemy resurfaces briefly for a final stand before dying. Another purpose of the resurrection is so that the player can see clearly how the hero has evolved throughout the story. Has the hero changed? More important, does the hero have the answer to the question posed by the story? The resurrection might also be in the form of an internal revelation for the character that the player might not have foreseena trick ending: "No, LukeI am your father." The Return with the RewardNow the story is over, and the hero returns to his ordinary world to resume life as normal. The player gets to see the hero enjoy the benefits of the reward, and the story is over. This is the last stage in the circular story form. The story returns completely to its starting point so that comparisons can be drawn between the hero before and after. However, a neatly tied-up story is not always desirable. Sometimes it is nice to leave a few questions open. One of the most popular forms of ending for a story is the "new beginning." In this type of ending, the story continues in the imagination of the player long after the game is completed. The player is left asking, "What happens next?" and the way is left open for a continuation or a sequel. The most obvious example of this is Half-Life . The story line for this game contains a last-minute plot twist. Just when you think Gordon Freeman is about to escape, he is accosted by a man in black (who has been covertly watching Gordon during the entire game) and is offered two choices. We won't spoil the surprise for those of you who have not played the game to completion; suffice to say that it is certainly an unexpected twist. The reward in this case has mutated from freedom to something else entirely. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 148