Section 5.1. Challenges of Organizing Information

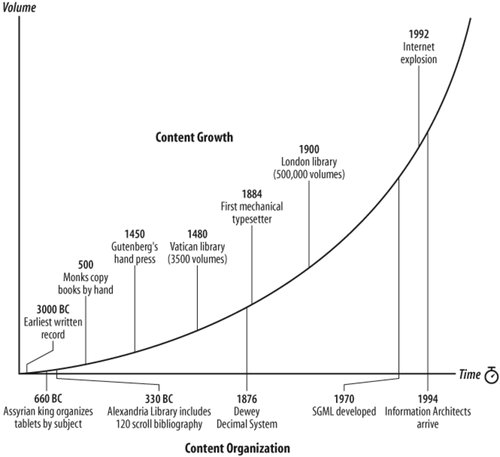

5.1. Challenges of Organizing InformationIn recent years, increasing attention has been focused on the challenge of organizing information. Yet this challenge is not new. People have struggled with the difficulties of information organization for centuries. The field of librarianship has been largely devoted to the task of organizing and providing access to information. So why all the fuss now? Believe it or not, we're all becoming librarians. This quiet yet powerful revolution is driven by the decentralizing force of the global Internet. Not long ago, the responsibility for labeling, organizing, and providing access to information fell squarely in the laps of librarians. These librarians spoke in strange languages about Dewey Decimal Classification and the Anglo-American Cataloging Rules. They classified, cataloged, and helped you find the information you needed. As it grows, the Internet is forcing the responsibility for organizing information on more of us each day. How many corporate web sites exist today? How many blogs? What about tomorrow? As the Internet provides users with the freedom to publish information, it quietly burdens them with the responsibility to organize that information. New information technologies open the floodgates for exponential content growth, which creates a need for innovation in content organization (see Figure 5-1). Figure 5-1. Content growth drives innovation And if you're not convinced that we're facing severe information-overload challenges, take a look at an excellent study[*] conducted at Berkeley. This study finds that the world produces between one and two exabytes of unique information per year. Given that an exabyte is a billion gigabytes (we're talking 18 zeros), this growing mountain of information should keep us all busy for a while.

As we struggle to meet these challenges, we unknowingly adopt the language of librarians. How should we label that content? Is there an existing classification scheme we can borrow? Who's going to catalog all of that information? We're moving toward a world in which tremendous numbers of people publish and organize their own information. As we do so, the challenges inherent in organizing that information become more recognized and more important. Let's explore some of the reasons why organizing information in useful ways is so difficult. 5.1.1. AmbiguityClassification systems are built upon the foundation of language, and language is ambiguous: words are capable of being understood more than one way. Think about the word pitch. When I say pitch, what do you hear? There are more than 15 definitions, including:

This ambiguity results in a shaky foundation for our classification systems. When we use words as labels for our categories, we run the risk that users will miss our meaning. This is a serious problem. (See Chapter 6 to learn more about labeling.) It gets worse. Not only do we need to agree on the labels and their definitions, we also need to agree on which documents to place in which categories. Consider the common tomato. According to Webster's dictionary, a tomato is "a red or yellowish fruit with a juicy pulp, used as a vegetable: botanically it is a berry." Now I'm confused. Is it a fruit, a vegetable, or a berry?[

If we have such problems classifying the common tomato, consider the challenges involved in classifying web site content. Classification is particularly difficult when you're organizing abstract concepts such as subjects, topics, or functions. For example, what is meant by "alternative healing," and should it be cataloged under "philosophy" or "religion" or "health and medicine" or all of the above? The organization of words and phrases, taking into account their inherent ambiguity, presents a very real and substantial challenge. 5.1.2. HeterogeneityHeterogeneity refers to an object or collection of objects composed of unrelated or unlike parts. You might refer to grandma's homemade broth with its assortment of vegetables, meats, and other mysterious leftovers as heterogeneous. At the other end of the scale, homogeneous refers to something composed of similar or identical elements. For example, Ritz crackers are homogeneous. Every cracker looks and tastes the same. An old-fashioned library card catalog is relatively homogeneous. It organizes and provides access to books. It does not provide access to chapters in books or collections of books. It may not provide access to magazines or videos. This homogeneity allows for a structured classification system. Each book has a record in the catalog. Each record contains the same fields: author, title, and subject. It is a high-level, single-medium system, and works fairly well. Most web sites, on the other hand, are highly heterogeneous in many respects. For example, web sites often provide access to documents and their components at varying levels of granularity. A web site might present articles and journals and journal databases side by side. Links might lead to pages, sections of pages, or other web sites. And, web sites typically provide access to documents in multiple formats. You might find financial news, product descriptions, employee home pages, image archives, and software files. Dynamic news content shares space with static human-resources information. Textual information shares space with video, audio, and interactive applications. The web site is a great multimedia melting pot, where you are challenged to reconcile the cataloging of the broad and the detailed across many mediums. The heterogeneous nature of web sites makes it difficult to impose any single structured organization system on the content. It usually doesn't make sense to classify documents at varying levels of granularity side by side. An article and a magazine should be treated differently. Similarly, it may not make sense to handle varying formats the same way. Each format will have uniquely important characteristics. For example, we need to know certain things about images, such as file format (GIF, TIFF, etc.) and resolution (640x480, 1024x768, etc.). It is difficult and often misguided to attempt a one-size-fits-all approach to the organization of heterogeneous web site content. This is a fundamental flaw of many enterprise taxonomy initiatives. 5.1.3. Differences in PerspectivesHave you ever tried to find a file on a coworker's desktop computer? Perhaps you had permission. Perhaps you were engaged in low-grade corporate espionage. In either case, you needed that file. In some instances, you may have found the file immediately. In others, you may have searched for hours. The ways people organize and name files and directories on their computers can be maddeningly illogical. When questioned, they will often claim that their organization system makes perfect sense. "But it's obvious! I put current proposals in the folder labeled /office/clients/green and old proposals in /office/clients/red. I don't understand why you couldn't find them!"[

The fact is that labeling and organization systems are intensely affected by their creators' perspectives.[§] We see this at the corporate level with web sites organized according to internal divisions or org charts, with groupings such as marketing, sales, customer support, human resources, and information systems. How does a customer visiting this web site know where to go for technical information about a product she just purchased? To design usable organization systems, we need to escape from our own mental models of content labeling and organization.

We employ a mix of user research and analysis methods to gain real insight. How do users group the information? What types of labels do they use? How do they navigate? This challenge is complicated by the fact that web sites are designed for multiple users, and all users will have different ways of understanding the information. Their levels of familiarity with your company and your content will vary. For these reasons, even with a massive barrage of user tests, it is impossible to create a perfect organization system. One site does not fit all! However, by recognizing the importance of perspective, by striving to understand the intended audiences through user research and testing, and by providing multiple navigation pathways, you can do a better job of organizing information for public consumption than your coworker does on his desktop computer. 5.1.4. Internal PoliticsPolitics exist in every organization. Individuals and departments constantly position for influence or respect. Because of the inherent power of information organization in forming understanding and opinion, the process of designing information architectures for web sites and intranets can involve a strong undercurrent of politics. The choice of organization and labeling systems can have a big impact on how users of the site perceive the company, its departments, and its products. For example, should we include a link to the library site on the main page of the corporate intranet? Should we call it The Library or Information Services or Knowledge Management? Should information resources provided by other departments be included in this area? If the library gets a link on the main page, why not corporate communications? What about daily news? As an information architect, you must be sensitive to your organization's political environment. In certain cases, you must remind your colleagues to focus on creating an architecture that works for the user. In others, you may need to make compromises to avoid serious political conflict. Politics raise the complexity and difficulty of creating usable information architectures. However, if you are sensitive to the political issues at hand, you can manage their impact upon the architecture. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 194

]

]  ]

]  ] It actually gets even more complicated because an individuals needs, perspectives, and behaviors change over time. A significant body of research within the field of library and information science explores the complex nature of information models. For an example, see "Anomalous States of Knowledge as a Basis for Information Retrieval" by N.J. Belkin,

] It actually gets even more complicated because an individuals needs, perspectives, and behaviors change over time. A significant body of research within the field of library and information science explores the complex nature of information models. For an example, see "Anomalous States of Knowledge as a Basis for Information Retrieval" by N.J. Belkin,