The Project-Based Organization and Classical Management Theory

|

We define a PBO as one in which:

the majority of products made or services offered are against bespoke designs.

The PBO may be stand-alone, making products for external customers, or a subsidiary of a larger firm, making products for internal or external customers. It may even be a consortium of firms that collaborate to make products for third parties (Katzy and Schuh 1998). (Throughout the rest of the chapter, we use the word "product" to mean product or service" for simplicity.) We previously described why classical management theory, developed as the basis for the management of the functional, hierarchical, line management organization, is inappropriate for the project-based organization (Turner and Keegan 1999). Classical management (Mintzberg 1979; Huczynski 1996; Morgan 1997) is based on the work of Smith (1776), Taylor (1913), Fayol (1949), Weber (1947), and Williamson (1975):

-

Smith proposed that economic improvement comes from a constant drive for greater efficiency. This striving for greater efficiency still pervades management thinking. We have previously called it the Economic Orthodoxy (Turner and Keegan 1999).

-

Taylor developed concepts of job design. Based on his scientific management thinking, the jobs of the organization are precisely defined, the competencies required to do the job described, and people found to fill the roles. This standard approach of assigning the person to the previously defined job, and not vice versa, we call the Human Resourcing Orthodoxy.

-

Fayol and his followers (Urwick 1943) designed organizations with administrative routines and command structures through which work could be planned, organized, and controlled. From this comes the concept of the organization structure, a single model of the organization and its functions, which is used for multiple purposes, including its governance, operational control, and knowledge and people management. The focus on a single model for the organization we call the Organization Structure Orthodoxy.

-

Weber (1947) said unfortunately this led to the creation of dehumanizing bureaucracies. The subsequent developments of human relations and neo-human relations (Huczynski 1996) merely put a humanistic gloss on the dehumanizing nature of the bureaucratic organization identified by Weber.

-

Williamson (1975) invoked transaction cost economics to explain the nature of the firm. He showed that two different types of customer-supplier relationship are adopted, hierarchies or markets, depending on whether the production machinery is designed specifically for the task at hand or can be used more generally. Hierarchies are adopted for products made for internal customers and markets for external ones.

Classical management theory works well, where the work of the organization is stable (Mintzberg 1979; Morgan 1997) and the customers' requirements and the technology used are slow to change. Job roles can be identified independently of people doing them, stable command and control structures can be put in place, and the whole structure can make itself more and more efficient through habitual incremental improvement (Turner 1999). Stable functions can be defined because both the work of the functions and the intermediate products that pass between them are well defined and unchanging, leading to the functional approach to work. Such organizations work like machines (Burns and Stalker 1961; Mintzberg 1979; Morgan 1997).

The ideas of Smith, Fayol, and Taylor, and the associated orthodoxies, are at best inappropriate for the PBO, and sometimes positively damaging.

-

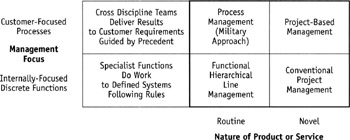

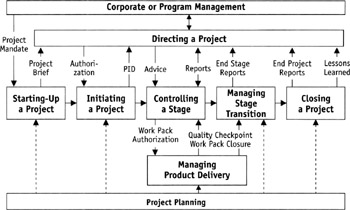

Because every customer's requirement is different, a unique, novel, and transient project must be undertaken to deliver every product or service (Turner 1999). This means the work of each function changes for every order, as does the intermediate products passing between them. This in turn means different customer-focused processes must be adopted for the completion of every order, see Figure 1 (Turner and Peymai 1995; International Organization for Standardization 10006 1996; CCTA 1996; Turner 1999). Figure 2 shows a version of customer-focused processes recommended by Projects in Controlled Environments (PRINCE) 2 (CCTA 1996). It is therefore not possible to define a single model for the organization to cover all circumstances. A different model must be developed for governance, the control of different operations, and for the development of the knowledge and people. Thus the Organization Structure Orthodoxy does not apply to the PBO.

Figure 1: Customer-Focused Processes versus Internally-Focused Functions (Turner and Peymai 1995)

Figure 2: Customer-Focused Processes Recommended by PRINCE 2 (CCTA 1996) -

Because work is always changing, it is not possible to define job roles precisely, nor independently of the person fulfilling the role. People with a different type of competence must be found; those who are familiar with the technology and knowledge of the firm but are able to work in unfamiliar, unstructured situations (Keegan et al. 1999). The individuals determine what job roles are required by the task and adapt their work accordingly. This requires different approaches to people development, and means the Human Resourcing Orthodoxy is inappropriate for the PBO.

-

It is therefore not possible to aim for efficiency. Indeed, efficiency works against effective project management. A drive for efficiency reduces the ability to flexibily respond to risk and the uncertain, changing nature of projects (Turner and Keegan 1999; Turner 1999). The Economic Orthodoxy can be positively damaging for the PBO.

-

In some PBOs, the nature of the projects and customers are such that new command and control structures need to be created for every project, and some times even at each stage of a project. Some PBOs can have stable command and control structures, but others, particularly those undertaking large projects for a few customers, cannot. This requires organizations to adopt several models for their governance and control, several organization structures.

-

More recently (Turner and Keegan 2001) we have shown from a transaction cost perspective that PBOs adopt wholly different approaches to their governance than classically managed ones. Hybrid structures are adopted regardless of whether the product is being made for an internal or external customer. In order to manage the uncertainty in the bespoke product and the bespoke production process, a direct relationship must be maintained between the project team and the customer.

Thus, we need to find new theories for the management of the PBO to replace those of Smith, Taylor, and Fayol.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207