The Economics of Wi-Fi in Public Networks

|

|

What is the economic pull to grow wireless public networks? The previous section of this chapter described the advantages of 802.11 in private networks. How then will public networks grow into acceptance in our economy? In an ideal world, some form of ubiquitous wireless coverage would extend to at least every residence and small business in a metropolitan area. After achieving that goal, extending the coverage to small towns and farms could occur at a rapid pace, assuming a business model propels that growth.

Although the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was intended to bring competition to the local loop, some six years after its passage, less than 10 percent of U.S. residences enjoy any choice in their local telephone service provider. Competition will never come in the local loop, but rather to the local loop. The act prescribed a formula for competitors to lease facilities (copper wire and switch space) from incumbent service providers. One of the reasons for a lack of competition in the local loop is simply the cost of deploying competing strands of copper wire.

According to studies performed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the cost to install a copper loop plant depends on the density of households in the service area. It can range from $500 per household in the cheapest urban sites to a typical $1,000 in dense suburban areas and ascend to $10,000 a loop in outlying rural areas. Economies of scale apply here. A competitor cannot come close to matching incumbent costs on a loop plant, because a competitor with a low market share has, effectively, rural density (and costs) even in an urban area.[5] A competitor to an incumbent telephone company must then consider its ROI on a per-customer basis. If the competitor realizes $40 per month, for example, on a customer, the ROI period could be very long. If a wireless service provider could persuade the customer to purchase his or her own customer premises equipment (CPE), the wireless competitor could potentially be more competitive than any other form of competitive service compared to the incumbent telephone company.

The following sections explore how 802.11 could propagate from enterprise networks in dense population centers to public networks and stretch to even the most rural areas. The current debate is whether that propagation will occur top down (that is, as deployed and operated by monolithic, century-old telecommunications carriers) or from below with "mom 'n pop" entrepreneurial operators providing broadband Internet access to their neighbors, schools, and libraries. Community networks pose yet another revolution-from-below scenario where broadband is provided free or nearly free of charge by community volunteers.

Hot Spots

At the time of this writing, the focus of the 802.'11 industry is on hot spots-that is, locations where laptop-equipped Internet surfers are likely to congregate for the short term (a coffee shop or airport) or reside for the long term (a hotel or multiple dwelling unit [MDU]). This is largely a function of the limited range of off-the-shelf access points (APs) (50 to 100 meters depending on conditions), access to a broadband Internet source, and a ready power source. In order to be commercially viable, a hot spot must incorporate all of these elements in one time and space. According to Allied Business Intelligence, "WLAN is extending its domain beyond the home and enterprise and is rapidly growing in popularity for public hot spot applications. The need for data connectivity on the go is being spurred by the increasing number of notebooks and PDAs that have WLAN adapters. North American WLAN public hot spot subscriber revenues are expected to increase to $868 million by 2006."[6]

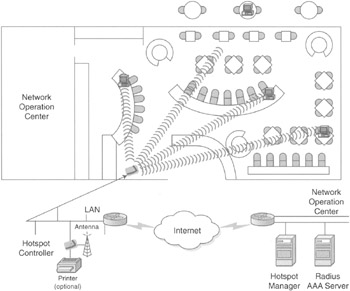

Figure 8-2: Wi-Fi deployment in a cafe or coffee shop hot spot, Source- Pronto Networks

Cafes (Coffee Shops) Wireless hotspot technology allows a cafe-owner to generate additional sources of revenue by offering customers wireless broadband Internet access. Offering wireless Internet access encourages customers to stay longer and spend more, allowing the cafe to capture more revenue per customer. One example of this is T-Mobile's relationship with coffee shop chain Starbuck's. T-Mobile is installing hotspots in thousands of Starbuck's worldwide. Competitors to both Starbuck's and T-Mobile are installing hotspots in coffee shops.

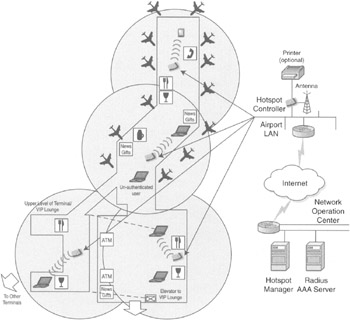

Airports Airports were perhaps the first and most obvious place for hot spot technology. Business travelers needed to access their e-mail and web sites while transiting through airports. Dial-up Internet access was and still is inconvenient because a user must either connect to a pay phone or have access to an airline's private club (however, American Airlines' Admiral's Club now offers T-Mobile's 802.11 service) where dial-up access is available. The deployment of wireless service enables the business traveler to access e-mail and web sites from almost any location in the airport (including aircraft).

Airports have also lost an important source of revenue with the advent of cell phones-pay phone revenue. Business travelers no longer dash to the banks of airport telephones to make calls and check voice mail. Rather, they use their cell phones for which the airport earns no revenue. The deployment of airport hot spots could serve to generate the revenue lost with the declining popularity of pay phones (see Figure 8-3).

Figure 8-3: Wi-Fi deployment in an airport, Source- Pronto Networks

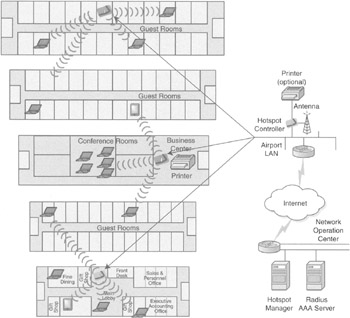

Hotels Like airports, hotels have derived revenue, in one form or another, from business travelers seeking access to e-mail and web sites. Business hotels must double as offices on the road for business travelers. This means convenient broadband Internet access must be available in order to remain competitive. Efforts to run CAT 5 wire through business hotels have encountered difficulties because of the high cost and potential inconvenience of hotel guests not being able to gain access to the network on the first try. Providing Wi-Fi for guests spares the hotel operator the expense of running CAT 5 wire throughout the hotel structure. Users should also find gaining access to the network more convenient on Wi-Fi than they would on wired Ethernet. Like airports, hotels have seen their revenues generated from guest telephone calls drop off from the increased cell phone use. The deployment of a hot spot in a hotel could offset that lost revenue (see Figure 8-4).

Figure 8-4: Wi-Fi deployment in a business hotel, Source- Pronto Networks

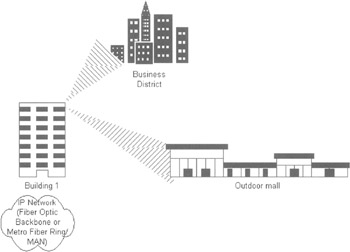

MDUs MDUs include apartment buildings and condominiums or other high-density dwellings. The attractiveness of the MDU market is that subscribers are concentrated on one space and can be served with a minimum number of APs (see Figure 8-5).

Figure 8-5: Wi-Fi deployment in an MDU, also known as apartments or condominiums, Source- Pronto Networks

Turnkey Operators

A promising approach to spreading the coverage of 802.11 is the turnkey of 802.11 services via firms that provide local operators with back-office services to overcome the chief barrier to entry for this market-customer service and network administration. Similar to the early spread of dial-up Internet access services, local operator entrepreneurs can get into this market space for only a few thousand dollars. In the current context of these plans, the local operator offers service in hot spots and shares revenue with the service provider for every per-visit or monthly subscriber. The hot spot operator must, in most but not all cases, purchase the AP hardware and associated access software. The challenge for the local operator is to operate in enough hot spots to be economically viable.[7] Table 8-5 lists turnkey operators, their products and business propositions for local operators. This presents an opportunity for the entrepreneur to enter this market without the expense of maintaining a large engineering staff.

| Network Operator | Description | How to Make Money |

|---|---|---|

| Boingo | This is a hot spot service. Boingo requires the purchase of a $695 Colubris AP configured for authentication, as well as high-speed service and a static IP address. Boingo also offers WISP in a Box, which enables a hot spot to have its own network customers while also offering Boingo service. | Boingo pays a $20 bounty for each new member, and $1 per connection session at a hot spot location. For WISP in a Box, the revenue sharing is the same, but Boingo requires that its partners in this service charge no less than $12 per month, $6 per day, and $3 per hour. |

| AirPath | AirPath has several plans, including the AirPath Instant Hot Spot. AirPath also allows Boingo Wireless customers to roam on their network. | They offer a variety of equipment, starting at $695, and also have approved equipment that can be deployed. The advantage of their system is that the local operator keeps all the revenue from the local subscriber (from a single point or a network of hot spots) and receives partner revenue from other AirPath members using the point. |

| NetNearU | This firm offers several kinds of preconfigured hot spot services, but has little detail on their online site. Boingo Wireless subscribers can use NetNearU locations. | A NetNearU reseller wrote in to note that he resells the turnkey system either for $495 and gives venues 15 percent of the revenue in exchange for providing technical support and marketing, or for $695 with a 40 percent revenue cut for the location, but they're responsible for marketing and tech support themselves. |

| FatPort | FatPoint Complete: A hands-off managed solution for $199 a month, including Digital Subscriber Line (DSL) service, technical support, and what they label FatPoint Express. | Up to 40 percent revenue share. |

| Joltage | Joltage Networks intends to use its proprietary software to foster what it calls micro-ISPs or hot spots. The software handles all the back-end details of running a WISP, including security, billing, and administration. | Joltage is following a revenue-sharing plan where it will split the $24.99 monthly access fee with the hot spot providers. In homage to Avon, Joltage will pay providers to bring others into the service. Joltage says micro- WISPs using its patent-pending software can opt to provide Internet access free of charge. |

| Source: 802. 11b Networking News[a] | ||

|

[a]"Turnkey Hotspots," a report from 802.11b Networking News, http://80211b.weblogger.com/turnkey_hotspots.html. | ||

Reciprocal Compensation-Build It and They Will Pay You

One critical building block for the propagation of 802.11 is reciprocal compensation. Wi-Fi users must be able to access wireless networks wherever possible in order for this technology to take hold. One potential market driver for the building of public networks is reciprocal compensation. In reciprocal compensation, one operator pays another when a subscriber of the first operator logs into the network of the second operator.

A good example of this model can be found in the cell phone industry. Cell phone companies thrive on charging roaming fees. When a subscriber is making calls within his or her service area, the charge may be 10 cents a minute. However, once the subscriber travels outside his or her immediate service area and accesses another cell phone company's network, the subscriber is charged a roaming rate that may be as high as 80 cents or more per minute. The subscriber's cell phone company must share that revenue with the originating cell phone company.

When the Internet revolution took place in mainstream America in the mid-1990s, a number of Internet service providers (ISPs) became Competitive Local Exchange Carriers (CLECs) because under the legal regimen of the time, CLECs could command reciprocal compensation from Incumbent Local Exchange Carriers (ILECs) for dial-up Internet access calls. Thus, the CLEC boom was born. The prospect of Wi-Fi subscribers driving reciprocal compensation for network operators might be a major catalyst for the deployment of even more 802.11 APs, thus spreading public networks nationwide. The establishment of reciprocal compensation agreements between service providers and the creation and operation of clearinghouses where revenues for accessing various networks are distributed are well under way. Programs for reciprocal compensation, roaming fees, and revenue sharing may very well promote a build-it-and-make-money catalyst for the construction of public 802.11 access networks.

Turnkey operators are probably the key to the immediate future for the propagation of 802.11 as a residential broadband Internet technology. Currently, the technology is hobbled by a conservative mentality that focuses on a service footprint with a maximum radius of 50 meters-that is, it is confined to spaces where a significant number of subscribers are likely to congregate.

How then will the promise of true broadband Internet offering multiple megabits of bandwidth to the home be realized? The answer lies both in technology and business models. First, antenna technology is improving to where the range of an antenna can be measured in miles instead of meters. If the service can move out of the hot spot and into the neighborhood, broadband can become ubiquitous. Some new antenna products promise steerable technologies that will allow an antenna to offer service to a specific household miles from the antenna. With new antenna technologies, local operators could spring up to service their respective suburbs or small cities and towns.

Another technology hurdle that must be overcome is the bandwidth of the feed to the wireless AP. Currently, many hot spots can obtain speeds of only 1.54 Mbps from the local telephone company. As explored in Chapter 3, "Range Is Not an Issue," the deployment of a wireless metro area network (WMAN) would allow the distribution of wireless broadband citywide at speeds approaching 11 Mbps. Many hot spot operators resell bandwidth from a DSL or cable modem service, which is often less expensive than a T1.

The turnkey business model offers a number of advantages for both the local operator and the turnkey provider. The advantage for the local operator is the cost of maintaining a help desk. Other customer service functions are provided by the turnkey provider. Single calls to a help desk can cost a service provider tens of dollars per call. Furthermore, having network management provided by the turnkey provider also spares the local operator lots of money.

Making the Private Network Public-Layering

If public access hot spots can be established by enabling existing and proposed enterprise WLANs to deliver public Wi-Fi coverage, the market would be much closer to making wireless Wi-Fi availability ubiquitous. This approach is called layering. Layering uses existing WLANs from larger enterprises to provide the bandwidth for public networks (hot spots). Unlicensed enterprise systems often cover or spill coverage out onto prime urban property and locations frequented by potential Wi-Fi users.

Layering for enterprise networks involves installing a network management gateway that recognizes and differentiates between authorized users from the enterprise and public access visitors. Enterprise users can receive secure IP Security (IPSec) encrypted WLAN service-with their communications operating over a guaranteed bandwidth allocation securely separated from that of visitors making use of the network. Visitors are directed to a WISP login screen and experience typical public hot spot service. Layering provides additional revenue opportunities for WLAN implementations that can offset some of the implementation cost issues and hurdles faced by some IT managers. Figure 8-6 illustrates the process of layering.

Figure 8-6: Layering is the resell of corporate bandwidth to the public in nearby locations.

Security and Bandwidth Management Security concerns are addressed by the gateway that manages the subnet of APs and assigns different roles to different groups or classes of users. One of these roles is designated for visitors who are blocked from accessing the enterprise systems and are channeled to and through the hot spot gateway software. The gateway can also perform wireless link encryption (supporting IPSec and Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol [PPTP] encrypted tunnels) and authentication using a built-in database or links to existing Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service (RADIUS) servers. Virtual LANs (VLANs) are used to segment the traffic between private and public use. VLANs can also limit the bandwidth of the public use and cut back on it on an as-needed basis. This way, a business can sell its excess bandwidth to the public in a hot spot up to a mile away from the building, assuming it uses the right antenna technology.

The layering model vastly expands the community-based approach started by urban residential broadband users who began offering free Internet access over their DSL connections by letting others in their neighborhood connect through their 802.11b APs. Many existing and proposed enterprise WLAN locations could use layering to provide hot spot coverage. Enterprise offices that front onto public spaces and that frequently host visitors, auditors, or consultants can benefit both themselves and their tenants/visitors by offering WLAN layering. Location owners will also benefit from the improved enterprise WLAN implementation economics that will be realized by offsetting hot spot revenue sharing against capital and operating costs.[8]

WISP ROI for Wireless Access via 802.11

A strong motivation for the deployment of 802.11 access could come from incumbent ISPs. Most ISPs have long been dependent on cooperation from incumbent telephone companies to deliver their services to their subscribers. Most telephone companies offer a competing ISP service. ISPs could free themselves of that dependency by deploying their own wireless access infrastructure. An ISP moving into this market space could endear itself with the small business community by offering a dial-a-bandwidth service in competition with the local telephone company. Bandwidth is usually sold by telephone companies in denominations of T1 (1.54 Mbps) and the rates range from $300 to $500 depending on the market and up to $10,000 per month depending on the distance. If an enterprise requires more than 1.54 Mbps, it is forced to buy another full 1.54 Mbps from its service provider at the going rate ($1,000 per month in many cases). Plans where the business is charged by the megabit or gigabit are also available. The company will also have to pay a monthly service fee to an ISP to connect to the Internet if that is not included in its bandwidth cost. Table 8-6 presents a comparison of these costs.

| Component | Regional Bell Operating Company (RBOC) | WISP |

|---|---|---|

| Data | 1.54 Mbps at $500 a month (includes Internet access) | 1.54 Mbps, less than $100 a month. |

| Local phone service | $50 per line a month | No cost for interoffice calls on the WLAN to other IP addresses; calls to PSTN numbers are 3 cents per minute. |

| Long distance | 3 to 7 cents per minute for all calls | Free interoffice calls on the WAN; other calls are 3 cents per minute. |

Offering Vo802.11 telephony services could also serve to distinguish the WISP from its competition and reduce churn. In addition, system integration services for the installation of WLAN equipment could be another source of revenue for the WISP.

Viral Growth of 802.11 Networks: Community Networks and the Mom 'n Pop WISP

Community Networks as an Industry Much has been written in the media about activists who are building community wireless networks. Wi-Fi may enable the creation of a new ISP industry that does not depend on local connections controlled by incumbent carriers such as the ILECs in the United States or the government Post, Telegraph, and Telephones (PTTs) elsewhere.

The scenario for community networks as an industry is likely to play out as it did for the mom 'n pop ISPs of the early Internet age (mid-1990s). However, just as small ISPs served as a goad for major carriers to provide Internet service, the grassroots wireless operators will do the same for wireless broadband. The grassroots operators will also likely serve as fertile technology and application incubators-their operators and constituents are just the kind of tech-savvy enthusiasts that produce the best and brightest ideas.

One outcome of the community wireless movement will be increased wireless broadband for less-wealthy areas and other forms of public service. If this happens, some of the promise of telecommunications as a democratizing force may be fulfilled. Particularly of interest will be the fate of the grassroots movement outside the United States, where microeconomic, community-owned approaches may be the best option to provide services to the population base. Strong precedents have been made for this tactic, including cellular build-out in certain markets. Interestingly, many sociopolitical overtones accompany this movement-in a way, this kind of movement is akin to the growth of broadcasting in its early years and implies the same sort of increased freedom of information. Over the next few years, some interesting stories will likely emerge from the community wireless movement.

| Component | Conventional | WISP |

|---|---|---|

| Local phone service (two lines) | $50 | $50 (assuming use of a cell phone) |

| Long distance | $100 ($.07 a minute) | $0 (assuming all calls are VoIP) |

| Video (cable versus video on demand) | $50 | $0 |

| Internet | $25 | $0 |

| Broadband service (DSL or cable) | $40 | $45 |

| Totals | $265 | $95 |

Timing Factors The community wireless movement has already shown real growth worldwide, with many organizations and individuals seeking to provide blanket coverage over a wide area or community. Projects have sprung up in Aspen, New York City, London, and many other locations. Another interesting factor is municipal and state support for Wi-Fi build-out as a source of broadband connectivity for areas not covered by traditional service providers. One challenge that will impede growth of the community wireless movement will be economics; until issues of who will pay are worked out, the business model will not be supportable. This is comparable to the early days of Internet connectivity, where early ISPs had to find ways to bill customers for service.[9]

[5]Fred Goldstein (telecommunications consultant), interview, November 28, 2002.

[6]Allied Business Intelligence, "Wireless LAN Public Hotspots: Assessment of Business Models, Service Rollouts, and Revenue Forecasts," www.wirelessreport.net/wireless-networks/july02/layeringtocreatepublichotspots.html.

[7]"Making Wireless Pay," The Economist, www.economist.com/business/displayStory.cfm?story_id=1067140, April 4, 2002.

[8]Tim Brooks, "Layering to Create Public Networks," www.wirelessreport.net/wire-lessnetworks/july02/layeringtocreatepublichotspots.html, July 2002.

[9]Chris Fine, "Watch Out for Wi-Fi," a white paper from Goldman Sachs, September 26, 2002.

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 96