Quality planning

|

|

We plan in quality management for the same reason that we plan in any other activity, in order to have a sensible, efficient and structured approach to a task. The chief purpose of quality planning is to produce a quality plan, that is, a description of how the project is going to achieve its quality requirement, and also what those requirements are. Like the overall project plan, of which the quality plan is a part, the quality plan serves two purposes: as a plan, and also as a communication tool, especially to engage key stakeholders in the quality management process.

A quality plan need not be long or complicated or expensive to produce. For small or simple projects, a single paragraph may suffice. Consider the quality plan shown here, used by a London-based company that ran a project to set up a new division to offer training courses to the public. It shows that a quality plan can be short and simple and straightforward. It also shows why it is useful to have a quality plan written down there can then be no doubt in the minds of those involved what is expected in terms of quality, and everyone is clear what the quality objective is: 60% or more 'Yes' votes. Of course in more complex projects, the quality plan will need to be more substantial.

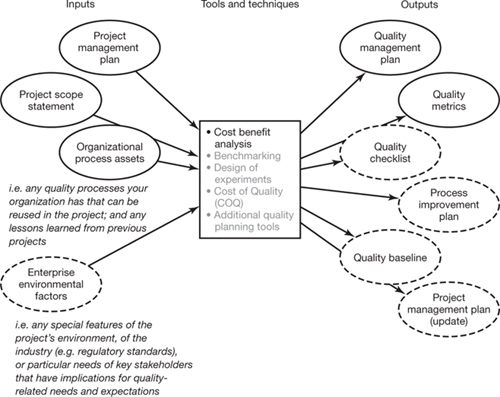

Let us walk though the steps in the quality planning process, as depicted in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1. The quality planning processThe most important and most commonly used inputs and outputs are in solid ovals, others are in broken-lined ovals. Similarly, the tools and techniques that are most essential are printed in black, the others in grey. Many industries and companies have their own quality planning techniques, and these are recognized under 'Additional quality planning tools'. Although that i s in grey, where your organization or industry has such tools and techniques, use them. In the inputs, it is obvious what the project management plan and the scope statement are. The PMBOK terms 'Enterprise environmental factors' and 'Organizational process assets' may be a little cumbersome and obscure, but the notes attached to each of those, above, explain what they are, and they are both useful categories of inputs to the quality planning process in many cases. Although the diagram above shows 'Enterprise environmental factors' in a broken-lined oval, implying that generally it is not the most important input to quality planning, an exception of course is in any regulated activity or safety-critical project, where the relevant regulations or legal requirements affecting quality must be used as inputs; in many cases the raw regulations and laws will have been incorporated into in-house procedural manuals, and so should be available as 'Organizational process assets'. The quality management plan is the most important output. It can be sufficient for the update to the project management plan to insert the quality management plan into the relevant place in the project management plan. A quality checklist is very useful, where appropriate, but derives from the quality management plan or the principles in it. Adapted from PMBOK Guide (p.184)

Inputs to the quality planning processBegin your quality planning by getting together the inputs. The quality plan will be part of the project plan, and quality management is an integral part of project management, so the project plan is an input: do not plan quality in isolation from the rest of the project plan. The scope statement is a vital input to quality planning, because if something is out of scope then you do not need to plan or manage its quality. For example, if the scope of a project to build a database is to build a proof of concept database which will not be used for operational purposes, then there may be a whole raft of quality requirements, for instance to do with longevity, maintainability and data security, which can be ignored. Continuing the example, there are many people in organizations whose job it is to enforce various IT standards on databases, and the quality plan coupled with the scope statement can be an effective way to communicate to them, in a professional and positive way, that in this project those standards and procedures can be ignored. Equally, when something is in scope, the consequential requirements for quality need to be understood and input to the quality planning process. So the scope statement is a key input to the quality planning process. Figure 8.1 lists two other inputs to the quality planning process: enterprise environmental factors and organizational process assets. Organizational process assets are simply assets your organization has that may be useful as inputs to the quality planning process, such as the following:

This input, organizational process assets, illustrates a general point, not just for quality planning but for project management too: do not make a long, expensive and bureaucratic affair out of it. Indeed, if you have to choose, choose too little rather than too much. Judgement and a sense of urgency and efficiency are indispensable; an unthinking rules-based approach is at most one step short of disaster. What does this mean? In respect of finding organizational process assets for use as inputs into quality planning, it means have a quick look around your organization for things that might be useful, and glance quickly through what you find to get a sense of whether it is likely to be useful to your particular project. The loss-making companies and failing government departments of the Western world are full of failed grey men and they usually are men who given half a chance will waste weeks and months on pointless documentation and regurgitation of irrelevant details and unnecessary process models. Don't get involved in them, and don't let them clog up your project. Have a quick look in the obvious places for input, do a quick assessment, and bend and adapt it to the needs of your project. Of course you should keep your sponsor informed of what you are doing, and enlist their help in deciding where to look for organizational process assets. The final input is enterprise environmental factors. This cumbersome term means things like:

Tools and techniques used in the quality planning processOnce you have gathered together your inputs you are ready to create your quality plan. The main tool is common sense, otherwise known as cost benefit analysis. There is no point doing quality management if the cost of doing it, in bureaucracy or whatever, exceeds the benefits. To take an example not from project management, if a fire breaks out, trapping you in your office, you want to use the fire extinguisher if there is one and try to escape immediately rather than hanging around conducting risk assessments and working out quality plans, because there is no benefit to doing them; the only possible benefit in that situation is to get you out of danger. That argument can be described as a cost benefit argument. A constant danger in real life where quality management is involved is that the costs of doing quality outweigh the benefits. It need not be so. It is your job as project manager to ensure that if there is a quality management aspect to your project it creates greater benefit than cost. Do not be put off by the term 'cost benefit analysis'. It does not need special financial skill or complicated spreadsheets, or any spreadsheet at all. It can simply be a matter of writing out a few rows, one for each benefit of using quality management in your project, and describing in words the costs and benefits of so doing. Table 8.3 is an example, from a hypothetical project to build a database for managing legacy documents needed to investigate insurance claims.

Table 8.3 shows the cost benefit argument set out in a qualitative, but objective and verifiable way. Like any plan, the quality plan must have clear objectives, and these are called quality objectives. This is simply saying that you should be clear about what it is you are trying to achieve in quality. Table 8.3 is an example of how not all quality objectives are directly related to the customer. One of the quality objectives concerns the comfort and health and safety of the employees who will use the database. This may have an indirect effect on the end customer, but the primary effect is on the employees, to ensure that they have a comfortable and safe experience when inputting data into the database. This is a valid quality objective. Once you have a qualitative cost benefit case, such as the example in Table 8.3, you can extend it if necessary, and perhaps add more quantification.

The other tools and techniques shown in Figure 8.1 for use in quality planning are essentially special kinds of cost benefit analysis, except that benchmarking can also help to generate options for quality objectives. Benchmarking means looking at what others are doing in the same or similar areas and how well they are doing it, so that you can try to match it. The underlying logic is that if someone else can do it, then you can too, potentially. Benchmarking applies to quality planning in two ways: you can find out what quality objectives others are working to, and you can find out what standards they are meeting or trying to meet for certain objectives. Remember that benchmarking can be both external, that is, against organizations other than your own, and internal, that is, against other parts of your own organization than the project you are managing. Cost of quality is a refinement of the general cost benefit analysis. Suppose we are running a war and we are using jet aircraft to fight the war. The jet engines break because of quality problems, causing our aircraft to crash. We can (a) do nothing, and keep buying new jets and training new pilots, (b) redesign the jet engines so that they break less often, (c) increase our engineering and maintenance capability, so that we service the jet engines more often, (d) buy a whole set of new jet engines from Clockland, a neutral country with a great engineering tradition. Each of these options has different costs, which need to be judged against the cost of existing quality, that is the cost of keeping on buying new jets and training new pilots. This thinking may lead to generating another option let us call it (a.i) which is to buy better ejector seats and parachutes perhaps we can live with the quality of the jet engines if we can stem the loss of pilots. Just as there is a cost structure in products and services and organizations, so there is a cost structure in quality, and one of the main benefits of the 'cost of quality' approach is that it helps us to understand the cost structure of quality. This enables us to generate options for planning quality. There are many other techniques and tools that can be used in planning quality, such as design of experiments, linear programming, and brainstorming. Do not be constrained in what tools and techniques you use, be pragmatic: if you have a useful tool or technique, use it. Usually there will not be time to learn a new tool for your project. Use what you already know how to use, or, even better, delegate the task to experts on quality in your organization if they are available. Quality planning is no different from planning as practised in general management; it is merely planning techniques applied to the specific field of quality management. You are likely to find that the tools that are most effective for you are the ones you are already experienced in. When planning quality, use objective, factual data as inputs to the planning process. Quality planning outputsThe main output of quality planning is the quality plan. This is not separate from the project plan, but is a section of it. Project planning is an iterative process, so you will start the quality planning process with a version of the project plan that has no section on quality management, and end up with an updated project plan that includes a section on quality. This section is the quality plan; they are not two different things. Quality plans vary in size according to the size and type of project. A small simple project may have no quality plan or a plan of a few lines. Large complex projects in safety-critical environments may need large and complex quality plans. Even the shortest quality plan should include the following:

If the quality plan is anything more than the smallest kind, it should also include:

In large or complex projects there can be great benefits to having peer or external reviews. Even if such reviews are intended to do no more than provide a fresh pair of eyes to look over certain aspects of what the project has done, this can be very valuable. Such reviews fall naturally under the heading of quality management. In some industries and companies external reviews are mandatory. Where there are to be such reviews, the quality plan should describe:

Having set quality objectives, the project will need to measure performance against the objectives. If it can't be measured it won't be managed, as the saying has it. The quality plan should specify the metric to be used to measure quality. In the context of quality management a metric is a system of measurement. (Note that it is not the measurement itself.) An example of a metric is given by the following instructions:

This example leaves much of the detail of the metrics implicit in terms such as 'standard ... questionnaire', but for this organization it states what the metric is and how it will be deployed on the project. Another example is as follows:

Quality metrics are an essential part of the quality plan. Other possible outputs of the planning process are checklists, a process improvement plan, and a quality baseline. Checklists are a simple but effective tool for improving quality, and are worth using wherever appropriate. Short, simple checklists are best. Where the project plan includes a section for the process improvement plan, updates to it should be an output from quality planning, but in practice this applies only to large and complex projects. The quality baseline is simply the baseline for quality, which is vital because otherwise the metrics will not have any practical meaning. Baselines can be very simple, for example: 'Baseline for SQEP project team members: In April 2006 at the start of the project two of 18 members of the project team had the skills and experience that will be necessary by the December 06 primary test target date.' Or, as an engineering example: 'Mean time between failures for the Mk.IX jet engine systems at the start of the project is 92 days; pilot death/downgrade rates from mid-air Mk.IX failure is 51%.' Both of these examples are baselines that enable improvement, or worsening, of quality to be measured. |

|

Top of Page