43 - Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume I - The Lung, Pleura, Diaphragm, and Chest Wall > Section X - The Diaphragm > Chapter 53 - Tumors of the Diaphragm

Chapter 53

Tumors of the Diaphragm

Robert J. Downey

The diaphragm is commonly involved with neoplasms, such as malignant pleural effusion or malignant peritoneal disease, but only rarely is the diaphragm the source of either benign or malignant processes. The presentation, evaluation, and treatment of these uncommon benign and malignant primary tumors of the diaphragm are discussed in this chapter.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

There are few publications on the subject of primary neoplasms of the diaphragm, reflecting the rarity of these tumors. Grancher (1868) is commonly credited with providing the first description of a primary diaphragmatic tumor, a benign fibroma, unsuspected until discovered at autopsy; other authors give primacy to Clark (1886) for a report of a primary lipoma of the diaphragm. Isolated case reports have predominated in subsequent reports and have been summarized in five major reports published by Nicholson and Whitehead (1956), Wiener and Chou (1965), Anderson and Forrest (1973), Olafsson and associates (1971), and finally, a total of 113 patients from the literature reviewed by Mandal and associates (1988). In a recent review of pediatric patients with primary diaphragmatic sarcomas, Raney and associates (2000) classified the management and prognosis of this small subgroup of patients, as is subsequently presented. For most lesions, a focused discussion has been best performed in case reports; therefore, for each lesion presented, the most thorough and most recent reports have been referenced.

PRESENTATION

A review of the case reports available in the literature suggests that diaphragmatic tumors are not associated with any characteristic symptoms. About 50% of the patients were asymptomatic, and the lesion was discovered either incidentally on radiographs or at the time of surgical exploration performed for unrelated reasons. If any symptom is characteristic, it would be that of a sense of lower chest discomfort or heaviness, possibly with referred pain to the top of the shoulder. Larger masses may give rise to compression of adjacent structures, such as the lung, causing cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis, or the heart, with lower extremity edema having been noted if venous return is compromised. Other physical findings appear rare, although some authors have noted masses palpable in the upper abdomen, or bulging through rib interspaces.

Evaluation before surgery is almost exclusively radiographic. Older reports, such as that of Ackerman in 1942, suggested fluoroscopy in conjunction with the performance of diagnostic pneumoperitoneum and pneumothorax; subsequent reports suggested the use of angiography. These measures are rarely used today, having been replaced by ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, as discussed by Yeh (1990), Brink (1994), and Kanematsu (1995) and their colleagues, respectively.

Given the rarity of diaphragmatic lesions, it is reasonable to suggest that evaluation should be directed toward consideration of the possible presence of more common benign or malignant lesions arising in proximity to, but not from, the diaphragm, as well as the presence of normal diaphragmatic anatomic variants that may be confused with neoplasms. These distinctions can be very difficult. The differential diagnosis can be summarized as follows: the diaphragm may be involved by nonneoplastic processes such as infections (including tuberculosis), hematomas, congenital abnormalities, or hernias, or secondarily involved by neoplasms metastatic to the diaphragm, as noted by Funatsu (1998) and Williams (2001) and their associates. In both of these reports, the metastatic disease was believed to have occurred through or at a diaphragmatic stoma, as described in Chapter 48. In the case reported by Funatsu and colleagues (1998), the original abdominal tumor was an advanced colon carcinoma, and in the other patient reported by Williams and associates (2001), the original tumor was a granulosa cell tumor of the ovary that had been excised 15

P.778

years earlier. Organs in the region of the diaphragm may be involved by processes that may be confused with primary diaphragmatic processes; in particular, pleural, pulmonary, or peritoneal infections, or primary or secondary neoplastic diseases of the liver, lung, pericardium, thymus gland (in particular, thymolipoma), stomach, or spleen should be keep in mind.

EVALUATION

If the initial test suggesting the presence of a lower thoracic cavity density is a chest radiograph, decubitus films may suggest the presence of a free-flowing effusion. Further evaluation will usually consist of some combination of CT scans, MR imaging, and ultrasound. Structural abnormalities of the diaphragm, such as lobulations, localized eventrations, slips, and a hypertrophic crus, may simulate neoplastic masses. However, such structural abnormalities can usually be distinguished from neoplastic processes by their appearance; for example, Ferguson and Westcott (1976) and Yeh (1990), Dagenais (1995), and Rozenblit (1998) and their associates discussed how lobulations are usually multiple, and eventrations generally conform to or retain the overall shape of the diaphragm. Distinguishing a mass apparently arising from the diaphragm from one originating within the lung parenchyma may be facilitated by reconstructions of CT images, if a low-attenuation plane can be seen between the mass and the diaphragm. The radiologic literature suggests that further support for localizing a mass within the lung may be offered by imaging suggesting irregular margins with the nearby lung, by the presence of acute angles between the diaphragm and the mass, and by focal volume loss in the lung, with pulmonary vessels and bronchi appearing to curve into the lesion. A pleural origin for a mass is suggested by the presence of obtuse angles between the lesion and the diaphragm. Imaging of herniated hollow viscera through the diaphragm may be enhanced by the use of oral or intravenous contrast. Ultrasound or MR imaging of the liver may be helpful in identifying a mass as a portion of the liver parenchyma. The choice of the wide range of currently available diagnostic imaging modalities will depend largely on the suspected diagnosis, but to some extent, extensive radiographic investigations may be replaced by video-assisted thoracic surgical techniques (VATSs), laparoscopy, or both because these offer the possibilities of both diagnosis and therapy.

PRIMARY BENIGN NEOPLASTIC LESIONS

The most commonly reported benign neoplasm of the diaphragm is the lipoma. Other reported benign diaphragmatic lesions include fibromas, congenital cysts, bronchogenic cysts, chondromas, angiomas, lymphangiomas, hemangioendotheliomas, rhabdomyofibromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas as well as an angioleiomyoma recorded by van Rijn and associates (2000) and a solitary fibrous tumor reported by Norton and colleagues (1997) (Table 53-1).

Table 53-1. Primary Benign Neoplastic Lesions of the Diaphragm | |

|---|---|

|

Lipoma

As previously noted, the first reported case dates to that reported by Clark in 1886, with about 27 subsequently reported cases. Over half of these cases were previously unsuspected findings at autopsy; the symptoms attributed to these lesions in the remaining patients were largely those of vague lower chest wall discomfort. There do not appear to be any reported cases in pediatric patients, but given that the majority came to light at either at autopsy or as asymptomatic radiographic findings, it is possible that they are present but undiagnosed in the pediatric population. Multiple authors, including Kalen (1970) and Gallia (1968), as well as Ferguson and Westcott (1976), Tihansky and Lopez (1988), and Papachristos and colleagues (1998), have provided descriptions of the radiologic appearance of lipomas, suggesting that by and large, they appear as sharp-bordered, smooth, possibly lobulated masses The reported lipomas are usually described pathologically as encapsulated, ranging in size from 1 to 16 cm, and with the same gross appearance of lipomatous tissue found elsewhere throughout the body. As they appear to arise from the substance of the diaphragm, the reported cases often have been noted to have an hourglass or a dumbbell appearance because of protrusions into both the thoracic and abdominal cavities, extending through

P.779

centimeter-sized defects in the diaphragm, with residual diaphragmatic muscle fibers being interdigitated with the fatty tissue. Wiener and Chou (1965) summarized the reported cases and noted that they arise predominantly from the posterolateral portion of the left hemidiaphragm; although, essentially every portion of the diaphragm has been reported as being involved. Tihanski and Lopez (1988) reported bilateral lipomas of the diaphragm, and Oyar and colleagues (2002) reported a rare entity of bilateral diaphragmatic crural lipomas. The diagnosis may be suggested by the findings of fat-density mass on CT. Treatment is excision with removal of as little diaphragm as is necessary, with surgery being performed largely to provide a definitive diagnosis, although these lesions can grow to such a large size as to compromise ventilation, as reported by Papachristos and associates (1998). Sampson and colleagues (1960) provided a case report of a lipoma apparently undergoing degeneration into a liposarcoma; however, although liposarcomas of the diaphragm have been reported by Froehner and colleagues (2001), degeneration may reasonably be held to be a rare event.

Congenital Cysts

A second group of benign lesions predominating in collected series is cystic formations, such as a bronchogenic cyst reported by Rozenblit (1998) and Dagenais (1995) and their colleagues. Mesothelial or teratoid cysts were noted to make up to 35% of benign lesions in the series of diaphragmatic tumors by Olafsson and associates (1971).

|

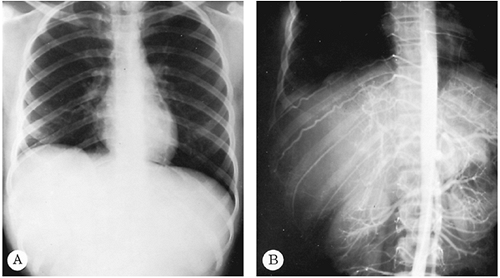

Fig. 53-1. Posterior radiograph of the chest revealing an elevated right hemidiaphragm. Suggestion of a mass occupying the lateral three-fourths of the right hemidiaphragmatic leaf is noted. B. Aortogram of the same patient demonstrates displacement of the normal vascular structures in the liver by a large neurofibroma of the diaphragm. Hypertrophy of the intercostal muscle is visualized clearly on this aortogram. |

Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors (neurilemoma and neurofibroma) of the diaphragm have been discussed by McClenathan and Okada (1989) as well as by Urschel and co-workers (1994). The presentation of these tumors is too varied to summarize meaningfully, other than to say that about 50% came to attention because of symptoms, with the remainder being diagnosed incidentally by radiographs performed for apparently unrelated reasons (Fig. 53-1). However, it is of interest to note that numerous investigators, including Trivedi (1958), Wiener and Chou (1965), and McClenathan and Okada (1989), recorded that one half of the reported neurogenic tumors (both benign and malignant) of the diaphragm were associated with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, clubbing of the fingers, or both. These are rare findings in other primary diaphragmatic tumors. Only one patient with clubbing of the fingers was recorded in a study of nonneural tumors of the diaphragm collected by Wiener and Chou (1965). It is appropriate to note that three fourths of diaphragmatic neurogenic lesions are benign, and about one half have a pedunculated attachment to the diaphragm.

P.780

Treatment

Surgical resection of all benign lesions represents definitive treatment and offers a uniform excellent prognosis. Resection must be considered for any benign mass either to confirm the diagnosis or to relieve symptoms when present. The diaphragmatic defect may be closed primarily if the defect is small, but more often than not a prosthetic patch (Gore-Tex PTFE) is necessary. At times, the entire hemidiaphragm needs to be replaced.

PRIMARY MALIGNANT NEOPLASTIC LESIONS OF THE DIAPHRAGM

Most of the reported cases of malignant tumors have been of mesenchymal origin (Table 53-2), which is not surprising given the cell structure of the diaphragm. The histologic types are varied. Included are reports of such rare tumors as: (a) leiomyosarcoma, by Parker (1985) as well as by Strauch (1999), Blondeel (1995), and Cho (2001) and their associates; (b) malignant fibrous histiocytoma, by Tanaka (1982), Yamamoto (1994), and Puls (2002) and their colleagues; and (c) fibrosarcomas, by Sbokos and associates (1977) (Fig. 53-2). Relatively unique tumors such as epithelioid hemangioendothelioma have been reported by Bevelaqua and colleagues (1988), primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) by Smerdely and associates (2000), hemangiopericytoma by Seaton (1974), and an extraskeletal osteosarcoma by Song and co-workers (2002).

Malignant diaphragmatic tumors in children are rare. However, rhabdomyosarcomas have been reported in young children by a number of authors. Incidentally, a rhabdomyosarcoma has also been reported in a young adult by Midorikawa and associates (1998) that was very aggressive, and the patient died within 1 year of diagnosis. In children, the course is usually not as rapidly fatal. Gupta (1999) and Vade (2000) and their colleagues each published a case in a 2 - and a 3-year-old boy, respectively. At the time of Gupta and colleagues' (1999) report, the authors stated that there were only three previously reported cases. The recently published summary article by Raney and colleagues (2000) of pediatric patients reported to the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group, although limited in patient number, probably represents the best information for these tumors in pediatric patients to date. The presentation of the malignant tumors often resembles that of the benign tumors of the diaphragm, with the exception that symptoms of locoregional spread may be present.

Table 53-2. Primary Benign Neoplastic Lesions of the Diaphragm | |

|---|---|

|

Treatment

In case reports, surgical resection with or without chemotherapy or radiation therapy was often performed in an attempt to cure. The effectiveness of surgical resection alone is difficult to evaluate because many of the cases were reported for their radiologic interest, without long-term outcomes being provided. However, for the small number of cases with outcomes data provided, the prognosis, even after apparently curative resection, appears grim. Because most patients with primary diaphragmatic malignancies came to medical attention because of symptoms usually indicating locoregionally advanced disease, long-term survival was only rarely achieved, with most patients suffering either local or distant metastatic recurrences.

The report by Raney and associates (2000) from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group recommends that, because disease in the pediatric population is usually locoregionally advanced at presentation, initial surgical intervention

P.781

should be limited to biopsy; complete resections at presentation were rare in their experience. Given proximity to vital structures, radiation therapy was difficult to deliver safely. Therefore, the Study Group recommends induction chemotherapy to be followed by either surgical resection and postoperative irradiation or preoperative radiation therapy and then surgical resection. With this treatment plan, 5 of 15 patients were without recurrent disease at last follow-up, and the remaining 10 had recurrent disease with a median disease-free survival of 1 year. Essentially, all recurrences were locoregional; all patients with recurrent disease died, with a median survival after first treatment of 1.6 years. How great a survival benefit this rigorous therapeutic approach will have remains to be seen (Senior Editor's comment).

|

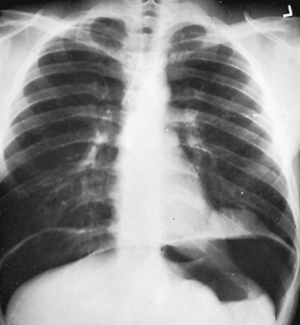

Fig. 53-2. The diagnosis of a diaphragmatic tumor was easily confirmed by a pneumoperitoneum. This tumor was excised and found to be a fibrosarcoma. |

REFERENCES

Ackerman AJ: Primary tumors of the diaphragm roentgenologically considered. AJR Am J Roentgenol 47:711, 1942.

Anderson LS, Forrest JV: Tumors of the diaphragm. AJR Am J Roentgenol 119:259, 1973.

Bevelaqua FA, Valensi Q, Hulnick D: Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. A rare tumor with variable prognosis presenting as a pleural effusion. Chest 93:665, 1988.

Blondeel PN, et al: Primary leiomyosarcoma of the diaphragm. Eur J Surg Oncol 21:429, 1995.

Brink JA, et al: Abnormalities of the diaphragm and adjacent structures: findings on multiplanar spiral CT scans. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163:307, 1994.

Cho Y, et al: A case of leiomyosarcoma of the diaphragm. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 7:297, 2001.

Clark FW: Subpleural lipoma of diaphragm. Trans Pathol Soc London 38:324, 1886.

Dagenais F, et al: Bronchogenic cyst of the right hemidiaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg 59:1235, 1995.

Ferguson DD, Westcott JL: Lipoma of the diaphragm: report of a case. Radiology 118:527, 1976.

Froehner M, et al: Liposarcoma of the diaphragm: CT and sonographic appearances. Abdom Imaging 26:300, 2001.

Funatsu K, et al: A case of a solitary metastatic diaphragmatic tumor-relation to the peritoneal stomata of the diaphragm. Radiat Med 16:363, 1998.

Gallia FJ: Nodular lesion of the diaphragm. JAMA 203:725, 1968.

Grancher M: Tumeur vegetante du centre phrenique du diaphragme. Bull Soc Anat Paris 1868, p. 4385.

Gupta AK, Mitra DK, Berry M. Primary embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the diaphragm in a child. Pediatr Radiol 29:823, 1999.

Kalen NA: Lipoma of the diaphragm. Scand J Respir Dis 51:28, 1970.

Kanematsu M, et al: Dynamic MRI of the diaphragm. J Comput Assist Tomogr 19:67, 1995.

Mandal AK, Lee H, Salem F: Review of primary tumors of the diaphragm. J Natl Med Assoc 80:214, 1988.

McClenathan JH, Okada F: Primary neurilemoma of the diaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg 48:126, 1989.

Midorikawa Y, et al: Rhabdomyosarcoma of the diaphragm: report of an adult case. Jpn J Clin Oncol 28:222, 1998.

Nicholson F, Whitehead R. Tumors of the diaphragm. Br J Surg 43:633, 1956.

Norton SA, et al: Solitary fibrous tumour of the diaphragm J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 38:685, 1997.

Olafsson G, Rausing A, Holen O: Primary tumors of the diaphragm. Chest 59:568, 1971.

Oyar O, Yesildag A, Gulsoy UK. Bilateral and symmetric diaphragmatic crus lipomas: report of a case. Comput Med Imaging Graph 26:135, 2002.

Papachristos IC, et al: Gigantic primary lipoma of the diaphragm presenting with respiratory failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 13:609, 1998.

Parker MC: Leiomyosarcoma of the diaphragm: a case report. Eur J Surg Oncol 11:171, 1985.

Puls R, et al: Tumour of the diaphragm mimicking liver. Eur J Radiol 41: 168, 2002.

Raney RB, et al: Soft-tissue sarcomas of the diaphragm: a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group from 1972 to 1997. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 22:510, 2000.

Rozenblit A, et al: Case report: Intradiaphragmatic bronchogenic cyst. Clin Radiol 53:918, 1998.

Sampson CC, et al: Liposarcoma developing in a lipoma. Arch Pathol 69: 506, 1960.

Sbokos CG, et al: Primary fibrosarcoma of the diaphragm. Br J Dis Chest 71:49, 1977

Seaton D: Primary diaphragmatic haemangiopericytoma. Thorax 29:595, 1974.

Smerdely MS, et al: Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the diaphragm: case report. Pediatr Radiol 30:702, 2000.

Song HK, et al: Extraskeletal osteosarcoma of the diaphragm presenting as a chest mass. Ann Thorac Surg 74:565, 2002.

Strauch JT, et al: Leiomyosarcoma of the diaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg 67:1154, 1999.

Tanaka F, et al: Prosthetic replacement of the entire left hemidiaphragm in malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the diaphragm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 83:278, 1982.

Tihansky DP, Lopez GM: Bilateral lipomas of the diaphragm. NY State J Med 3:151, 1988.

Trivedi SA. Neurolemmoma of the diaphragm causing severe hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy. Br J Tuberc 52:214, 1958.

Urschel JD, Antkowiak JG, Takita H: Neurilemmoma of the diaphragm. J Surg Oncol 56:209, 1994.

Vade A, et al: Imaging of primary rhabdomyosarcoma of the diaphragm. Comput Med Imaging Graph 24:339, 2000.

van Rijn AB, van Kralingen KW, Koelma IA: Angioleiomyoma of the diaphragm. Ann Thorac Surg 69:1928, 2000.

Wiener MF, Chou WH: Primary tumor of the diaphragm. Arch Surg 90: 143, 1965.

Williams RJ, et al: Metastatic granulosa cell tumour of the diaphragm 15 years after the primary neoplasm. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 19:516, 2001.

Yamamoto H, et al: Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the diaphragm: report of a case. Surg Today 24:744, 1994.

Yeh HC, Halton KP, Gray CE: Anatomic variations and abnormalities in the diaphragm seen with US. Radiographics 10:1019, 1990.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203