129 - Exposure of the Cervical Esophagus

Editors: Shields, Thomas W.; LoCicero, Joseph; Ponn, Ronald B.; Rusch, Valerie W.

Title: General Thoracic Surgery, 6th Edition

Copyright 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

> Table of Contents > Volume II > The Esophagus > Section XXIV - Malignant Lesions of the Esophagus > Chapter 152 - Surgical Palliation of Inoperable Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Chapter 152

Surgical Palliation of Inoperable Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Robert J. Korst

Robert J. Ginsberg

Carcinoma of the esophagus, be it squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, continues to be lethal, with minimal hope of total cure. At diagnosis, fewer than 5% of patients have localized disease without regional node involvement. Another 50% of patients have locoregional disease. The rest present with distant metastases. It is unlikely that more than 10% of patients presenting with carcinoma of the esophagus will be cured of their tumor. For the rest, the most one can hope for is palliation of symptoms. The aim of palliation in the group with advanced disease is to improve the quality of the limited life remaining for the patient.

DYSPHAGIA

The most frequent symptom requiring surgical palliation is dysphagia. Obstructing tumors of the esophagus vary in the amount of dysphagia produced, but the progressive interference with the ability to eat is surely one of the most distressing symptoms one can have. When the patient aspirates or can only swallow liquids because of complete obstruction, intervention, often surgical, is required. The ability to swallow saliva and to eat as normally as possible is the goal of palliative treatment.

ASPIRATION

Pulmonary symptoms resulting from aspiration of saliva (caused by complete dysphagia) or of food (because of esophagorespiratory fistulae) are life-threatening and can be ameliorated surgically.

PAIN

Thoracic pain caused by invasion of an unresectable tumor cannot be relieved surgically, other than by using neurosurgical ablative techniques. These patients are best treated nonsurgically.

SURGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Regardless of the palliative technique used, the morbidity and mortality of any procedure are significant because of the advanced stage of the disease and the poor nutritional status of most patients. The more major the surgical intervention, the more likely that postoperative complications will occur. The selection of the appropriate palliative technique should be modulated by several factors, including the experience of the surgeon, the expected survival time of the patient, and the general condition of the patient at the time of intervention. One must always remember that nonsurgical methods of palliation are available. Radiation therapy can effectively shrink a tumor and alleviate pain and dysphagia. Combination platinum-based chemotherapy has been used effectively for the same purpose (see Chapter 151). Neither of these nonsurgical treatments has been effective in managing a tracheoesophageal fistula, and they may, in fact, aggravate the condition. Despite this fact, some fistulae close after radiation therapy.

This chapter deals exclusively with those surgical procedures aimed at improving the ability to swallow without dysphagia or aspiration.

PALLIATIVE ESOPHAGEAL RESECTION

The philosophy regarding palliative esophageal resection depends on the criteria used to define unresectable disease. These criteria vary from surgeon to surgeon and from institution to institution.

Whenever a carcinoma of the esophagus can be resected completely without the expectation of leaving residual disease, a curative resection should be considered. All patients

P.2314

with local disease or disease limited to regional lymph nodes (N1) are likely to be considered for this form of curative therapy. In many instances, unfortunately, at the time of surgery, only an incomplete palliative resection can be performed.

Those patients with lymph node involvement beyond the regional area (M1a) or with metastatic disease (M1) cannot be considered curable by surgical resection. Only in exceptional circumstances should surgical resection be performed as a palliative maneuver in these patients and only in those patients in whom total gross removal of tumor is possible. A successful surgical resection without postoperative complications provides good swallowing function quickly, but palliative resections are prone to excessive postoperative complications and mortality. In noncurative resections, the median survival time is less than 6 months, the combined mortality and morbidity exceeds 30%, and virtually no patient survives 5 years. In these patients, irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy offers as much hope for palliation as surgical resection, without the attendant postoperative problems, especially in tumors above the carina. Stoller and Brumwell (1984) demonstrated equal palliation by surgery or radiation therapy. Obstructing circumferential tumors below the carina are at times best treated by a palliative, incomplete resection, despite the inability to cure. In this location, the stricture produced by irradiation can result in significant dysphagia and poor quality of life.

Adenocarcinomas respond less quickly to radiation therapy, and the symptoms during the remaining few months of life may not be palliated by this form of treatment. Giuli and Gignoux (1980), however, reported that an incomplete resection results in recurrent local disease in approximately 40% of the patients with early recurrent dysphagia. Barbier and colleagues (1988a, 1988b) confirmed these findings. This fact must be considered before recommending a palliative resection for patients whose tumor cannot be resected completely.

ESOPHAGEAL BYPASS

In a small group of patients with esophageal carcinoma, resection is not technically possible, but nutritional and respiratory status and life expectancy are such that esophageal bypass can be considered as the prime mode of therapy to ameliorate the dysphagia. Included in this group are those in whom radiation therapy may be contraindicated (e.g., impending or actual tracheoesophageal fistulae or obstructing lesions at the lower end of the esophagus) or in whom irradiation or chemotherapy, or both, have failed.

The morbidity and mortality of such bypass procedures, however, are excessive (Table 152-1). In series by Orringer (1984) and Conlan and associates (1983), the operative mortality exceeded 20%, complication rates exceeded 50%, and median survival was less than 6 months. Orringer (1984) abandoned this approach.

The simplest method of bypass uses the presternal or preferably the retrosternal route, with the anastomosis in the neck performed by laparotomy and neck incision. The left or right intrathoracic approach, however, can be used, with the anastomosis created in the chest, above the obstruction, or in the neck. However, even contemporary series such as that of Aoki and associates (2001) confirm the high mortality rate (40%) resulting from esophageal bypass, suggesting that improvements in postoperative care over the past 20 years are less important than the overall debilitated condition of these patients in determining their outcome.

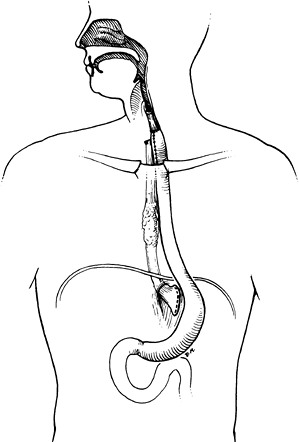

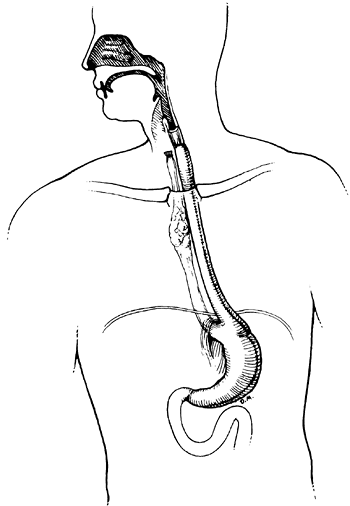

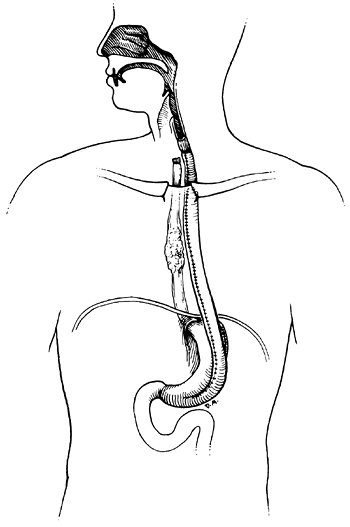

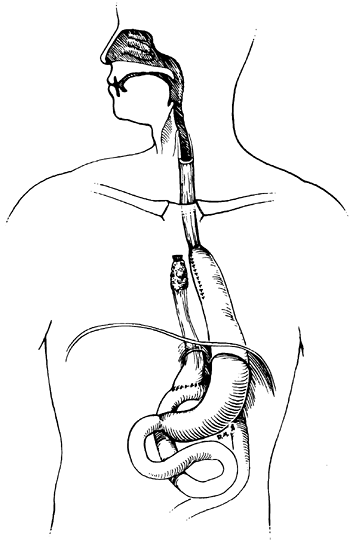

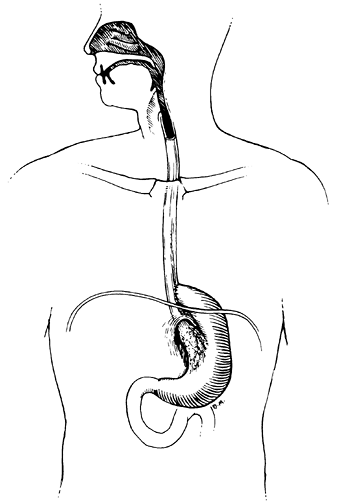

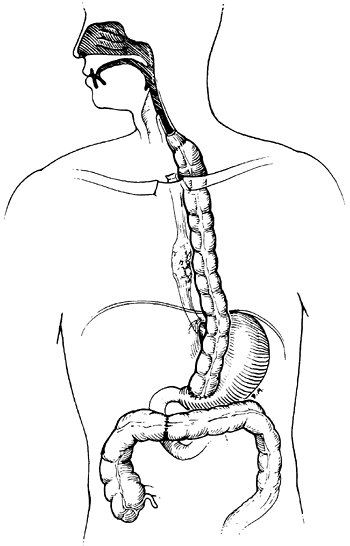

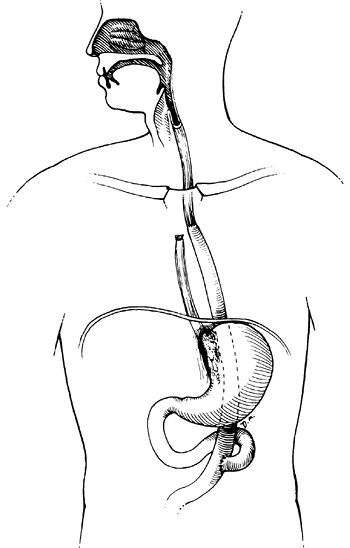

Gastric Tubes

Bypass using the whole stomach [our preference (Fig. 152-1)] or reversed (Fig. 152-2), as Heimlich (1972) advocated, or nonreversed greater curvature gastric tubes (Fig. 152-3), as Postlethwaite (1979) suggested, provides satisfactory swallowing. When using the entire stomach, the esophagus may be totally excluded and closed proximally and distally or, as recommended by Ong (1973), drained distally by a Roux-en-Y or simple jejunal loop (Fig. 152-4). An alternative drainage technique involves intubating the lower stump by simple tube esophagostomy, protecting this with omentum, and exiting the tube, usually a Malecot catheter, through the left upper quadrant anterior abdominal wall. After 1 month, this tube can be removed if it is bothersome, thus creating a potential tract and blow hole if problems arise.

Advocates of greater curvature gastric tubes, reversed or nonreversed, claim that the simplicity and rapidity of fashioning

P.2315

these tubes far outweigh the slightly higher leak rate at the cervical esophageal anastomosis.

Table 152-1. Results of Large Series of Bypass Procedures Performed for Unresectable Carcinoma of the Esophagus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Fig. 152-1. Whole-stomach bypass using the retrosternal route. Note that the esophagus has been excluded proximally and distally. |

|

Fig. 152-2. A reversed gastric tube bypass. The esophagus has been excluded proximally but is drained adequately distally through the gastroesophageal junction. |

|

Fig. 152-3. A nonreversed gastric tube bypass with proximal exclusion of the esophagus. We prefer this to the reversed gastric tube. |

Fundal Bypass

A modified Popovsky procedure mobilizing the fundus of the stomach to bypass localized esophagogastric tumors (Fig. 152-5) has been successful in highly selected cases. This technique was well described by Popovsky in 1980.

Colon Segments

Although any portion of the colon may be used, we prefer an isoperistaltic left colon transplant, with a vascular pedicle based on the left colic artery, placed in the retrosternal position (Fig. 152-6). We use this approach when gastric transposition cannot be considered.

Jejunal Loops

The jejunum has a more tenuous blood supply than the colon or stomach, and it is the least preferred bypass tube

P.2316

from neck to abdomen. Intrathoracic bypass using a Roux-en-Y jejunal loop, however, as described by Kirschner (1920) described and used by Ong (1973), is feasible, especially in esophagogastric tumors in which the stomach also must be bypassed (Fig. 152-7). When recommending any of these bypass procedures, one must remember that the patient has a limited lifespan and that the procedure chosen should be designed to provide the most rapid recovery and discharge from the hospital with successful palliation of dysphagia.

|

Fig. 152-4. An intrathoracic gastric bypass excluding the esophagus proximally but draining the distal esophagus into a loop of jejunum. |

Unfortunately, all of these bypass procedures have high morbidity and in-hospital mortality. One must be selective in recommending esophageal bypass for a patient with advanced, inoperable esophageal carcinoma, choosing only those patients with an expected survival that is meaningful and selecting the least morbid approach for the particular circumstance.

Extracorporeal Tubes

Akiyama and Hatano (1968) as well as Skinner and DeMeester (1976) advocated permanent extracorporeal bypass using plastic tubes inserted into a preformed cervical esophagostomy and abdominal gastrostomy. This approach, however, has not been accepted as a usual means of palliation. The patient's disfigurement and distress seem to far outweigh the possible benefits of this type of palliative procedure. It has been abandoned as a therapeutic option in most centers.

|

Fig. 152-5. A simple fundal bypass for a small gastroesophageal obstructing carcinoma. |

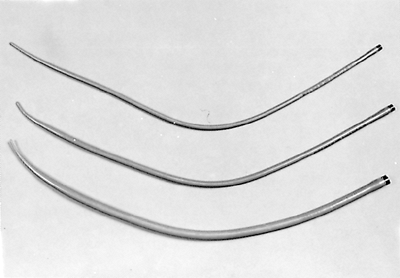

ESOPHAGEAL DILATION

Simple repeated esophageal dilation rarely provides satisfactory swallowing ability for any significant duration. Usually, symptoms are relieved for a few days or weeks at the most.

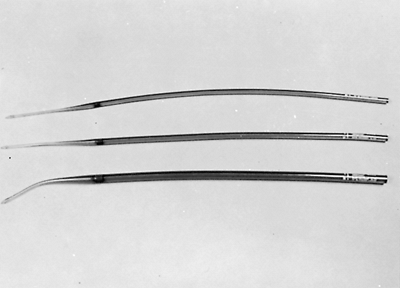

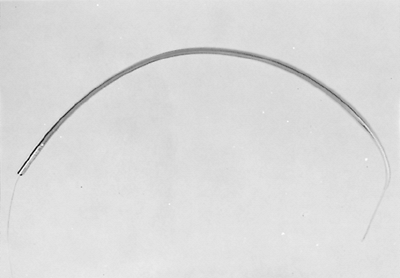

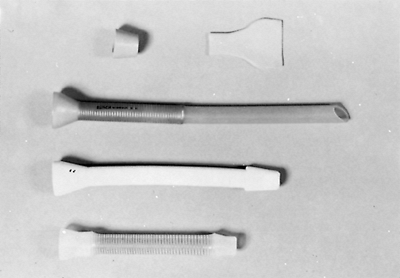

Dilation, however, usually is necessary before peroral intubation with plastic tubes or laser ablation. In selected circumstances, the tumor may need to be dilated to approximately 10 mm before placement of self-expanding metal stents as well. We prefer using either Maloney bougies (Fig. 152-8) if a guidewire is not required, or Savary bougies (Fig. 152-9) after the stricture has been successfully negotiated by a guidewire under fluoroscopic control (Fig. 152-10). In most cases, this procedure can be performed satisfactorily without the need for general anesthesia, using local anesthesia and mild intravenous sedation.

Many patients have already received radiation therapy, and care must be taken to dilate the stricture gradually because the risk of perforation by splitting the postirradiated

P.2317

carcinomatous stricture is significant. Often, the procedure must be repeated every few days or weekly, gradually increasing the bougie size over a few sessions to obtain a satisfactory lumen diameter before intubation.

|

Fig. 152-6. A retrosternal colon bypass with exclusion of the proximal esophagus. We prefer an isoperistaltic left colon based on the ascending branch of the left colic artery. |

ESOPHAGEAL INTUBATION

Various prostheses have been developed to intubate the esophagus, thereby relieving severe dysphagia or aspiration from tracheoesophageal fistulae. Although none of these prostheses restores perfectly normal swallowing, the new self-expandable metal stents may allow patients to eat relatively normal diets, provided the food is well chewed. In most series, median survival after tube insertion is approximately only 3 months, with few patients surviving beyond 1 year.

Expandable stents have virtually replaced plastic esophageal tubes as the prosthesis of choice for palliation of esophageal cancer. In addition, they have made the indications for bypass surgery and palliative resection even more rare.

Several advantages of expandable stents over traditional tubes are responsible for this change. They are simpler to place than plastic tubes. Deployment usually requires only intravenous sedation and flexible endoscopy with fluoroscopic guidance, whereas plastic tube placement may require

P.2318

general anesthesia and rigid esophagoscopy to push the tube into the correct position. The delivery system is more compact (8 to 12 mm), making the requirement for dilation before stent placement minimal, and unnecessary in many instances. Should the stent migrate or the tumor enlarge, another stent can be partially telescoped into the previously placed stent to traverse the new area of tumor. Complications associated with insertion of expandable stents appear to be less common than after traditional plastic tube placement, and finally, these stents possess greater flexibility and larger internal diameters (18 to 22 mm) than their plastic counterparts.

|

Fig. 152-7. An intrathoracic Roux-en-Y esophageal jejunal bypass with exclusion of the proximal esophagus. |

|

Fig. 152-8. Maloney bougies that we use for esophageal dilation when guidewires are not required. |

|

Fig. 152-9. Savary bougies for use with guidewires. |

|

Fig. 152-10. An example of a Savary bougie with the guidewire in place. |

If, at the time of initial placement, an expandable stent is malpositioned, it can usually be removed using endoscopic techniques, one of which is placing an esophageal overtube into the esophagus and grasping the stent with a biopsy forceps, pulling it into the overtube. Once an expandable metal stent is deployed for more than 24 to 48 hours, however, any uncovered portions of wire become embedded in the esophageal wall, making the stent virtually unremovable. Other disadvantages of these devices are the wide open reflux that can develop if the stent is placed across the gastroesophageal junction, although manufacturers are attempting to solve this problem with novel stent designs. The previous problem of tumor ingrowth through the porous stent wall was alleviated with the advent of covered stents. These newer models have a thin coating of silicone or polyurethane to prevent tumor ingrowth; unfortunately, the coating makes the prosthesis more likely to migrate than the uncovered versions.

The most common situation in which traditional tubes may still be indicated is when a chance exists that the prosthesis may have to be removed. This includes the stenting of lesions at the gastroesophageal junction, where unrelenting reflux may prove to be more troublesome than the initial dysphagia. Tumors within 2 cm of the cricopharyngeus require precise stent placement, which may be easier to accomplish with traditional tubes. If the tube should protrude into the pharynx above the cricopharyngeus, the resulting foreign body sensation in the pharynx may require stent removal. In such cases, the thin-walled Montgomery plastic tube may be preferable. Current investigative efforts, such as that of Bethge and Vakil (2001), are focusing on new expandable stent designs that would allow for their removal, such as plastic expandable stents, which also may be less expensive than their metal counterparts.

Expandable Metal Stents

Metal stents consist of an interlocking network or coil of metal wire, the pattern of which varies depending on the manufacturer. These stents are contained in a deployment system that is easily placed over a guidewire under fluoroscopic guidance. Tumor dilation is usually not necessary but may be needed when using a stent with a low expansile force. Currently, there are three commercially available systems in the United States.

Gianturco Z-stent

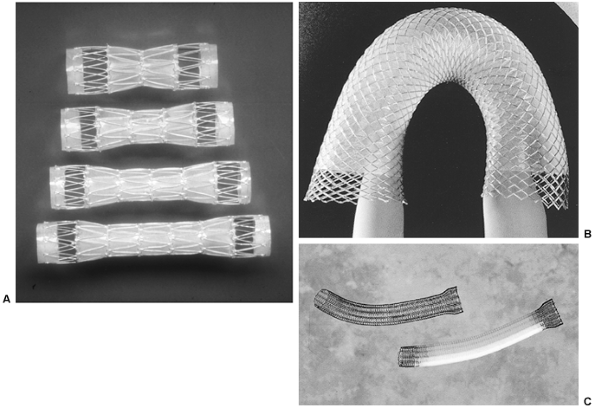

The wire mesh in the Gianturco Z-stent (Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston Salem, NC, U.S.A.) assumes a Z configuration when deployed (Figs. 152-11 and 152 12A). Originally

P.2319

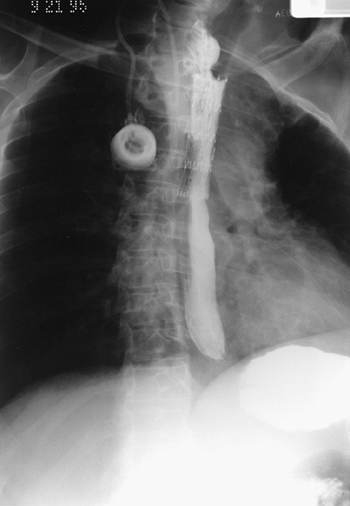

available only as an uncovered stent, the high rate of tumor ingrowth led to a version covered with silicone, which can be placed with a low morbidity and mortality, as described by Song and colleagues (1991). Barbs are present in an attempt to prevent migration, and this stent opens to a diameter of 18 mm. The Gianturco Z-stent is the only metal stent that does not shorten on deployment, making it especially useful near the upper esophageal sphincter. This device is also available with an attached antireflux mechanism (dual valve), which may make it more desirable when stenting across the gastroesophageal junction.

|

Fig. 152-11. Posteroanterior chest radiograph of a patient with a malignant esophageal obstruction and a Gianturco Z-stent bridging the tumor. |

|

Fig. 152-12. A. Assorted sizes of the covered Gianturco Z-stent (Wilson-Cook). B. Wallstent (Boston Scientific). C. Covered Ultraflex esophageal stent (Microvasive). |

Wallstent

The Wallstent (Schneider, Minneapolis, MN, U.S.A.) consists of a woven steel mesh that is available both uncovered as well as covered with polyurethane. In the covered version, the coating is centrally located, with the ends remaining uncovered in an attempt to reduce migration. Maximal diameters are 24 to 25 mm, and this stent shortens on deployment (Figs. 152-13 and 152 12B).

Ultraflex (Microvasive)

The Ultraflex model (Microvasive/Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, U.S.A.) consists of a knitted nitinol wire tube that initially was covered with a dissolving gelatin material to facilitate deployment. The proximal end is flared to discourage migration; covered as well as uncovered versions are available (Fig. 152-12C). This stent has the lowest expansile force of all available metal prostheses, and as a result, the stent may need to be dilated with a balloon to achieve adequate expansion. After placement, the device

P.2320

continues to slowly expand, not reaching full expansion until approximately 24 hours after insertion. Breakage of the stent has been reported by Kozarek and associates (1995). An advantage of this model is that if the stent is malpositioned and this is recognized at the time of initial placement, an endoscopic biopsy forceps can be used to grasp the proximal ring and the stent will collapse, allowing for its removal.

|

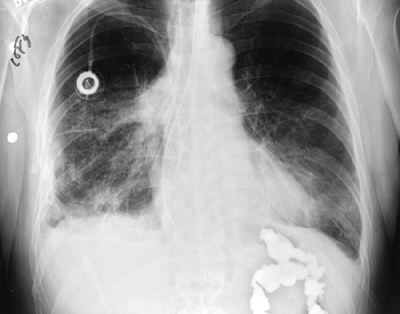

Fig. 152-13. Posteroanterior chest radiograph of a patient with a covered Wallstent placed for malignant esophagorespiratory fistula. |

Technique of Insertion

The patient is placed supine and sedated. Flexible esophagoscopy is performed, and using fluoroscopic guidance, the proximal and distal extent of the tumor is marked on the skin using metal markers. If the endoscope cannot be passed through the tumor, dilation may have to be performed, which is preferably done over a wire. A guidewire is placed through the tumor, and the delivery system is placed over the wire. The stent is then deployed across the tumor length previously delineated by the radiopaque markers. Another technique is the injection of thin barium into the tumor proximally and distally to mark the extent of disease. In addition, balloon dilation of the stent may be performed if the stent has a low expansile force and has not expanded sufficiently.

Postoperative Care

After the placement of any esophageal prosthesis and before beginning oral feeding, a radiograph of the chest and contrast-enhanced esophagography with dilute barium are performed to rule out perforation and to ensure the correct position of the prosthesis. The patient is instructed to eat carefully, chewing food well and using liberal amounts of liquid to clear the prosthesis after each meal. If a stent is placed across the gastroesophageal junction, the patient is advised not to lie completely supine after meals or while sleeping to avoid reflux and aspiration.

Table 152-2. Three Randomized Trials Comparing Immediate Results and Complications After Expandable Stent and Plastic Tube Placement for Inoperable Carcinoma of the Esophagus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results

As reviewed by Dittler and Pfister (1996), multiple uncontrolled series confirm the ease of placement and low early complication rate of expandable stents in patients with both malignant dysphagia and esophagorespiratory fistulae. Initial stent placement is successful in more than 95% of patients, and complication rates average less than 10%. Table 152-2 lists the immediate results and complications reported in the three existing randomized, controlled trials of metal stents versus plastic tubes. All three studies confirm the lower complication rates seen with expandable stents compared with conventional plastic tubes. However, late failure remains a problem regardless of the choice of prosthesis (Table 152-3). It is interesting to note that despite the larger diameter of these newer stents, the incidence of recurrent dysphagia after prosthesis placement remained similar between the two groups in two of the three studies.

With three different models of stents commercially available, the question arises as to which model will outperform the others. This issue was addressed in a recent clinical trial reported by Siersema and associates (2001) evaluating technical success, dysphagia relief, complications, and survival of 100 patients with malignant dysphagia randomized to receive the Ultraflex, Wallstent, or Z-stent. No significant differences were appreciated in any of these end points between these stent models. In this study, tumor overgrowth and stent migration remained the primary causes of stent failure in all three groups.

Plastic Tubes

The ideal tube should be easy to place, remain in position without migrating proximally or distally, and remain patent when a reasonable diet is followed, and should not erode into surrounding mediastinal structures. As yet, no tube is ideal. Although many designs are in use, most plastic tubes can be categorized by the technique of insertion: push per os or pull by way of laparotomy (or laparoscopy) and gastrostomy. As

P.2321

already discussed, these tubes are only used now in exceptional circumstances.

Table 152-3. Three Randomized Trials Comparing Longer-Term Functional Results After Expandable Stent and Plastic Tube Placement for Inoperable Carcinoma of the Esophagus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

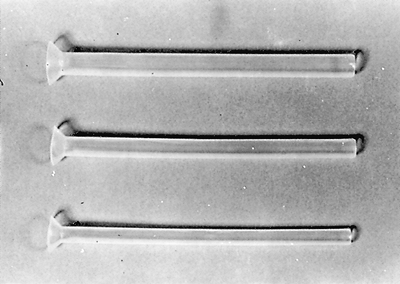

The peroral intubation, or push method, is by far the most commonly used technique for plastic tube placement. With flexible endoscopy, it can be applied to tumors throughout the thoracic esophagus and esophagogastric junction. The method usually does not require general anesthesia but does require preinsertion dilation. We prefer the Celestin (rubber) or Wilson-Cook (silicone) armored tubes of the Atkinson design (Fig. 152-14). Proctor-Livingston tubes have been used with success in South Africa.

After preinsertion flexible endoscopy, the tumor is dilated using Savary bougies over a guidewire, being careful not to dilate the stricture larger than the tube itself. The tube is then pushed into correct position, usually under fluoroscopic guidance using an introducing tube designed for this purpose, or the rigid esophagoscope, as shown in Fig. 152-15. At least 4 cm of tube should protrude distal to the tumor to avoid subsequent tumor overgrowth; however, when possible, it is desirable for the tube not to traverse the esophagogastric junction. Montgomery salivary tubes are softer and can be used to traverse a lesion within 2 cm of the cricopharyngeus. These silicone tubes have a soft consistency to minimize any foreign body sensation despite the flange often lying above the sphincter (Fig. 152-16).

|

Fig. 152-14. Three examples of endoprostheses designed for the push technique. Note the distal flange to prevent proximal slippage and the rubber dam to prevent reflux. |

Complications occur in approximately 20% of cases, and Liakakos and associates (1992) note that these include perforation (10%), erosion of the tube into contiguous structures with fatal hemorrhage or a pleural fistula, upward migration and regurgitation of the tube, and dislodgment and passage of the tube into the stomach. Further tumor growth proximally can occlude the tube and occurs in approximately 25% of patients successfully treated. This can be treated by stent replacement or insertion of a second tube above the first if stent removal is not possible.

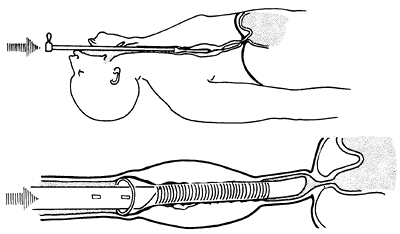

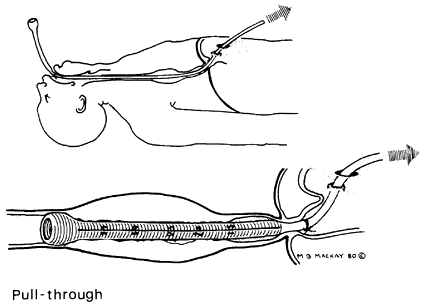

Intubation via laparotomy (the pull method) is reserved for those patients in whom the peroral technique cannot be used or when, during laparotomy, esophagectomy is abandoned because of inoperability. Techniques have now been developed to perform this procedure using a laparoscopic approach. The anesthetist passes the tube into the esophagus, and the surgeon pulls the introducer through a gastrotomy. The tube is then seated and the introducer amputated (Fig. 152-17).

Most authors favor the peroral push method over the pull method when plastic tubes are used. Kratz and colleagues (1989) demonstrated a lower complication rate (13% versus 58%), lower mortality (6% versus 40%), and longer median survival (3 months versus 2 months) when using the peroral route.

|

Fig. 152-15. Push method with rigid endoscopic techniques. Note that the end of the tube is above the gastroesophageal junction to avoid reflux. This placement is preferred whenever possible. |

|

Fig. 152-16. Examples of Montgomery salivary tubes for use in proximal esophageal obstruction. The proximal flange should be placed above the cricopharyngeus and is designed for use if a tracheostomy has been performed. |

P.2322

GASTROSTOMY AND JEJUNOSTOMY

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, as recommended by Stellato (1992), or operative gastrostomy or jejunostomy with open or laparoscopic approaches can be used to maintain the nutrition of a patient but fails to deal with the dysphagia. In the past, we seldom used this technique; however, we now find this approach useful as an adjunct to other palliative techniques (e.g., endoesophageal intubation). It can be especially important if the patient is receiving radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both, for palliation. Although the inability to swallow is devastating, the consequences of prolonged hunger and dehydration can be as morbid. These simple procedures can improve the patient's quality of life by improving nutrition and strength and should be considered in such individuals.

|

Fig. 152-17. Pull method. The tube eventually is cut off above the gastroesophageal junction whenever possible. |

LASER PROCEDURES

Restoration of swallowing ability by endoscopic removal of tumor by either photocoagulation therapy with neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers or photodynamic treatment with hematoporphyrin sensitization and argon pumped dye laser excitation has met with encouraging success. With either method, exophytic fungating tumors are more amenable to palliation than tumor extrinsically compressing the esophagus.

Photocoagulation Therapy

Both the carbon dioxide and Nd:YAG lasers destroy tumor by their coagulative effect. The latter laser is preferable because it can be delivered by fiberoptic endoscopy. Patients need not be anesthetized for the procedure. Usually, three or four sessions are required to produce an adequate lumen, and repeated treatments at monthly or more frequent intervals may be required to maintain the lumen.

The advantages of this technique are the absence of mortality or major morbidity, although perforation occurs in 4% to 5% of cases (Table 152-4). In expert hands, up to 90% of obstructing lesions can be opened, allowing the patient to swallow liquids or semisolid foods. Because this procedure can be done on an ambulatory basis, it has become an attractive palliative approach. A randomized trial reported by Low and Pagliero (1992) demonstrated its equal efficiency when compared with endoprosthesis insertion. Alderson and Wright (1990) compared this technique with endoprosthesis insertion and concluded that laser coagulation is best for short (less than 4 cm) lesions and that endoprostheses should be used for lesions longer than 4 cm.

The most important disadvantages of laser palliation are the repeated treatments that are usually necessary to maintain dysphagia relief for the remainder of the patient's life (see Table 152-4) and its inapplicability for tracheoesophageal fistulae. In an attempt to prolong the duration of palliation, Nd:YAG treatment has been combined with other modalities, including endoesophageal brachytherapy. In this regard, Spencer and colleagues (2002) randomized

P.2323

patients to Nd:YAG laser alone or laser plus brachytherapy (10 Gy; performed during the same session as the initial laser treatment) and determined that brachytherapy prolonged the dysphagia-free interval.

Table 152-4. Early Results with the Use of Neodymium:Yttrium-Aluminum-Garnet Laser Therapy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Photodynamic Therapy

The use of hematoporphyrin derivatives to sensitize malignant tumors to 630-nm light from a red argon pumped dye laser is effective in those tumors that are accessible to the argon laser beam. Skin, bladder, rectal, and pulmonary tumors have all been treated in this fashion. Obstructing esophageal tumors have been opened up by presensitizing the patients with hematoporphyrin derivatives and then using the laser endoscopically to destroy the tumor. The mechanism of action is likely the production of intracellular single oxygen radicals, which destroy the tumor cells.

McCaughan (1985, 1996), Thomas (1987), and Okunaka (1990) and their colleagues reported that this technique successfully reestablished swallowing function in as many as 90% of patients. Similarly, dysphagia scores improved in 91% of 77 patients treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT) in a recent series of patients with malignant dysphagia, reported by Luketich and co-workers (2000). When compared with the Nd:YAG laser in a randomized trial, PDT alleviated malignant dysphagia with equal efficacy and was associated with fewer perforations, according to Lightdale and associates (1995). Luketich (2000) and Lightdale (1995) and their co-workers reported that the disadvantages of PDT include the need for repeated endoscopies and treatments, as well as the risk of sunburn after administration of the sensitizing agent. However, Kashtan and associates (1999) note that newer sensitizing agents may decrease the incidence of sunburn.

This type of therapy is still investigational, and the exact application for palliation of esophageal tumors is unknown. Photodynamic therapy has been combined with irradiation in an attempt to produce an additive effect. The results of these combined therapies are as yet unknown.

TRACHEOESOPHAGEAL FISTULAE

The only methods that can deal with tracheoesophageal fistulae are exclusion, bypass, and intubation. Expandable stents represent a definite step forward in the management of this preterminal condition, such that it is a rare event that operation is required for a malignant esophagorespiratory fistula. Most reports of the use of these stents for esophagorespiratory fistulae reveal high success rates for closure of the fistula, often exceeding 95%, as demonstrated in the report by May and Ell (1998). Many of these patients can resume a near-normal diet as well. Stent migration is seen less often in this subset of patients than in those in whom the prosthesis was placed for the palliation of dysphagia. This observation is most likely because the stents placed across the gastroesophageal junction tend to migrate more often, but tumors in this location tend not to fistulize to the airway.

In a controlled prospective study, Siersema and colleagues (2001) found that all presently available models of covered stents have been reported to be successful in occluding malignant esophagorespiratory fistulae. Again, the covered Gianturco Z-stent is probably the best choice in the upper esophagus near the cricopharyngeus because this stent does not shorten on deployment, allowing more accurate placement. On rare occasions, stenting of the upper airway also may be required. Colt and colleagues (1992) have advocated airway stenting as best for occluding these fistulae versus esophageal stenting.

CONCLUSIONS

The palliation of obstructing or fistulizing carcinomas of the esophagus is not always easy. One cannot expect the median survival of these patients to be greater than 3 to 6 months. Self-expanding metal stents have revolutionized the treatment of these patients given their easy insertion, relatively low short-term complication rates, and reasonable functional results. Given the relative success with these stents, surgical resection and bypass are currently rarely indicated, but familiarity with these techniques is mandatory should a specific indication arise. Plastic stents are advisable in cases in which removal may be needed, but otherwise, these tubes are rapidly becoming obsolete. Despite the multitude of surgical techniques available, no one technique or stent suits every patient. The surgeon must be cautious in choosing the procedure that affords the patient adequate palliation with minimal morbidity and a short in-hospital stay.

REFERENCES

Akiyama H, Hatano S: Esophageal cancer: palliative treatment. Kyobu Geka 21:391, 1968.

Alderson D, Wright PD: Laser recanalization versus endoscopic intubation in the palliation of malignant dysphagia. Br J Surg 77:1151, 1990.

Aoki T, et al: Comparative study of self-expandable metallic stent and bypass surgery for inoperable esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 14:208, 2001.

Barbier PA, Becker CD, Wagner HE: Esophageal carcinoma: patient selection for transhiatal esophagectomy. A prospective analysis of 50 consecutive cases. World J Surg 12:263, 1988a.

Barbier PA, et al: Quality of life and patterns of recurrence following transhiatal esophagectomy for cancer: results of a prospective follow-up in 50 patients. World J Surg 12:270, 1988b.

Bethge N, Vakil N: A prospective trial of a new self-expanding plastic stent for malignant esophageal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol 96:1350, 2001.

Colt HG, Meric B, Dumon JF: Double stents for carcinoma of the esophagus invading the tracheo-bronchial tree. Gastrointest Endosc 38:485, 1992.

Conlan AA, et al: Retrosternal gastric bypass for inoperable esophageal cancer: a report of 71 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 36:396, 1983.

De Palma DG, et al: Plastic prosthesis versus expandable metal stents for palliation of inoperable esophageal thoracic carcinoma: a controlled prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 43:478, 1996.

P.2324

Dittler HJ, Pfister KGM: Palliation of esophageal cancer: stents and tubes. Dis Esophagus 9:105, 1996.

Eckhauser LM: Laser therapy for gastrointestinal tumors. World J Surg 16:1054, 1992.

Fleischer D, Sivak MH: Endoscopic Nd:YAG laser therapy as palliative treatment for advanced adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Gastroenterology 87:815, 1984.

Giuli R, Gignoux M: Treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus: retrospective study of 2400 patients. Ann Surg 192:44, 1980.

Heimlich HJ: Esophagoplasty with reversed gastric tube. Review of fifty-three cases. Am J Surg 123:80, 1972.

Hugier M, et al: Results of 117 esophageal replacements. Surg Gynecol Obstet 124:1058, 1970.

Kashtan H, et al: Photodynamic therapy of cancer of the esophagus using systemic aminolevulinic acid and a non-laser light source: a phase I/II study. Gastrointest Endosc 49:760, 1999.

Kirschner MB: Ein neues verfahren der oesophagoplastik. Arch Klin Chir 114:606, 1920.

Knyrim K, et al: A controlled trial of an expansile metal stent for palliation of esophageal obstruction due to inoperable cancer. N Engl J Med 329:1302, 1993.

Kozarek RA, et al: Prospective multicenter trial utilizing esophageal Z stent for dysphagia and TE fistulae. Gastrointest Endosc 41:353, 1995.

Kratz JM, et al: A comparison of endoesophageal tubes. Improved results with the Atkinson tube. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 97:19, 1989.

Liakakos TK, et al: Palliative intubation for dysphagia in patients with carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg 53:460, 1992.

Lightdale CJ, et al: Photodynamic therapy with porfimer sodium versus thermal ablation therapy with Nd:YAG laser for palliation of esophageal cancer: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 42:507, 1995.

Low DE, Pagliero KM: Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing brachytherapy and laser photoablation for palliation of esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 104:173, 1992.

Luketich JD, et al: Endoscopic photodynamic therapy for obstructing esophageal cancer: 77 cases over a 2-year period. Surg Endosc 14:653, 2000.

May A, Ell C: Palliative treatment of malignant esophagorespiratory fistulas with Gianturco-Z stents. A prospective clinical trial and review of the literature on covered metal stents. Am J Gastroenterol 93:532, 1998.

McCaughan JS Jr, Williams TE Jr, Bethel BH: Palliation of esophageal malignancy with photodynamic therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 40:113, 1985.

McCaughan JS Jr, et al: Photodynamic therapy for esophageal malignancy; a prospective twelve-year study. Ann Thorac Surg 62:105, 1996.

Okunaka T, et al: Photodynamic therapy of esophageal carcinoma. Surg Endosc 4:150, 1990.

Ong GB: The Kirschner operation a forgotten procedure. Br J Surg 60:221, 1973.

Orringer MB: Substernal gastric bypass of the excluded esophagus results of an ill-advised operation. Surgery 96:467, 1984.

Popovsky J: Esophagogastrostomy in continuity for carcinoma of the esophagus. Its use for unresectable tumors of the lower third of the esophagus and cardia. Arch Surg 115:637, 1980.

Postlethwaite RW: Technique for isoperistaltic gastric tube for esophageal by-pass. Ann Surg 189:673, 1979.

Riemann JF, Rucks CE, Demling L: Combined therapy of malignant stenoses of the upper gastrointestinal tract by means of laser beam and bouginage. Endoscopy 171:43, 1985.

Rontall E, et al: Laser palliation for esophageal carcinoma. Laryngoscope 96:846, 1986.

Siersema PD, et al: Coated self-expanding metal stents for esophagogastric cancer with special reference to prior radiation and chemotherapy: a controlled, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 47:113, 1998.

Siersema PD, et al: A comparison of 3 types of covered metal stents for the palliation of patients with dysphagia caused by esophagogastric carcinoma: a prospective, randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc 54:145, 2001.

Skinner DB, DeMeester TR: Permanent extracorporeal esophagogastric tube for esophageal replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 22:107, 1976.

Song HY, et al: Esophagogastric neoplasms: palliation with a modified Gianturco stent. Radiology 180:349, 1991.

Spencer GM, et al: Laser augmented by brachytherapy versus laser alone in the palliation of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and cardia: a randomised study. Gut 50:224, 2002.

Stellato TA: Endoscopic intervention for enteral access. World J Surg 16:1042, 1992.

Stoller JL, Brumwell ML: Palliation after operation and after radiotherapy for cancer of the esophagus. Can J Surg 27:491, 1984.

Thomas RJ, et al: High-dose photoirradiation of esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 206:193, 1987.

Wetstein L, et al: A prospective evaluation of endoscopic Nd-YAG laser therapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus [Abstract]. Chest 92:62S, 1987.

Wong J, et al: Results of the Kirschner operation. World J Surg 5:547, 1981.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 203