ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING AND PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

Before you even consider any undertaking in process improvement, you really should spend some time internalizing and institutionalizing the concepts in this section s title. If you re the kind of person who enjoys developing and building things for the pleasure of saying that you built it, you should seriously consider changing your work habits or finding a different line of work other than process improvement. If you prefer getting results regardless of who did the development, process improvement is for you.

We re all human, we all have some level of ego, and we would all like to believe that the work we do is new, cutting edge, and that we ve gone where no one has gone before. Thinking so makes us feel good about ourselves . But the reality is that there really isn t very much new under the sun. The information has always been out there and with the World Wide Web, the information is easy to access. To prove this point, I ve often challenged people in presentations and speaking engagements to name a topic on which they believe there is no existing information and to give me 15 minutes on the Web to find some information on the topic. I haven t lost this challenge yet. In process improvement, vicarious learning, reuse, adoption, and adaptation are everything!

What is vicarious learning and why is it so important in process improvement? Put in simple terms, vicarious learning is borrowing existing ideas, processes, approaches, and work products from others and modifying the borrowed things for use in your organization. By reading this book, you are engaged in vicarious learning.

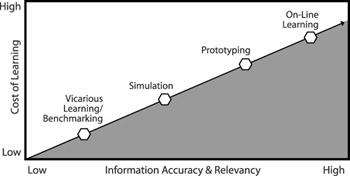

Why are vicarious learning, reuse, and adaptation so important in process improvement? The answer is money. It costs less money to borrow, modify, and reuse things than to build them yourself. There is an even greater cost saving when you borrow things that have already proven successful in other environments similar to yours. Figure 4.928 shows the relative cost and accuracy of knowledge or information acquired through the four major approaches to organizational learning.

In Figure 4.9, you can see that the cost of vicarious learning is the least expensive form of organizational learning and that online learning, which is learning by putting an idea or work product into full production, is the most expensive. Following is a discussion of each learning approach in the hierarchy in terms of process improvement and some pros and cons of each.

Figure 4.9: The Four Main Types of Organizational Learning

Vicarious Learning and Benchmarking

In terms of process improvement, vicarious learning and benchmarking simply means finding out what other organizations have done in terms of CMM or CMMI implementation and reusing their best practices while not repeating their mistakes. The physical activities involved in vicarious learning involve conducting tasks such as:

-

Doing Web searches on your topics or questions. One of the richest sources of process improvement information and literature is located on the Software Engineering Institute s Web site: www.sei.cmu.edu.

-

Reading books, technical papers, and articles (i.e., what you re doing right now). Including this book, there are more than seven after market tomes on CMMI and its implementation.

Example

An example of vicarious learning and benchmarking is finding process- related work products to be used in your organization. Let s say the concept of documenting project plans is new to your organization (yikes!). You and your SEPG or process action team (PAT) can spend weeks discussing and inventing a project plan template or you can spend less than 10 minutes downloading one from the IEEE Web site30 and then modifying it for use in your organization.

The primary physical activities involved in benchmarking are:

-

Defining and planning your benchmarking activities and goals

-

Searching and reading literature

-

Conducting benchmarking visits /interviews with select organizations

-

Analyzing the benchmark data collected for use in your organization

In relatively new industries (nanotechnology, for example), the return on effort in vicarious learning may be limited due simply to the relatively small body of knowledge that exists in a truly new area. However, this is not the case with software and systems process improvement. The body of knowledge in process improvement is rich in breadth and depth. Thousands of organizations in many different industries, platforms, and geopolitical cultures have used CMM or CMMI to improve their processes. [31] The number of best practices and lessons learned to be found and possibly reused is almost limitless. People whose egos won t let them think that others have gone before them or people who think they re too smart to learn from others will find it easy to say, yeah, but we re different. We re unique so we can t use other peoples work. Recognize such statements for what they are: an excuse for being afraid to learn!

A word of caution: Before you run off to start looking for best practices or embarking on a career of benchmarking, make sure you have a working definition for best practice and that you have very narrowly defined what you re looking for. Looking at other peoples work can become so interesting that it s easy to lose sight of your goal. One of the better definitions that I ve come across for the phrase best practice comes from The Gartner Group: [32]

A best practice is composed of policies, principles, standards, guidelines, and procedures that contribute to the highest, most resource-effective performance of a discipline. Best practices are based upon a broad range of experience, knowledge, and extensive work with industry leading clients .

There may be no single best practice for any given business process. A process design that works well for experienced, well-trained personnel may be inappropriate for less experienced users. Business processes may assume a prerequisite technology architecture infrastructure or costs that may not be feasible under a different set of circumstances. Globalism may make it unsafe to assume a standard set of factors required to implement successfully a best practice. Therefore, a series of best practices may be defined for each set of circumstances. Gartner Group has recognized that the management of best practices is a Knowledge Management challenge.

The key message in the above definition is that even though something is identified as a best practice for another organization, even one that is engaged in a business similar to yours, it is not necessarily a best practice for your organization.

Here are some additional criteria that will help you determine a best practice for your organization. [33] A best practice is one that:

-

When implemented will generate or cause measurable improvement in organizational or project performance

-

Is widely recognized as a best practice and has a proven track record (be careful of reputation versus demonstrated performance) Can be implemented in a wide variety of environments and business uses

-

Is consistent with your organization s culture and user patterns

-

Is simple and doesn t require five doctorate degrees to comprehend Is not dependent on the heroics of individuals to implement or execute

-

Can periodically be validated to still be the best

Vicarious Learning and Benchmarking Pros

The benefits of vicarious learning and benchmarking are:

-

Lower cost relative to other forms of organizational learning (although unplanned or poorly planned benchmarking can get quite expensive).

-

Faster speed relative to other forms of learning. For example, you can read the results of five processes used in other organizations much faster than the time it takes to test them in your own organization for results.

Vicarious Learning and Benchmarking Cons

The downside to this approach is that, because no two organizations are identical, the information culled from one organization s process may not be relevant or accurate in your organization. There are many variables affecting the results of process and process improvement methods and tools and not all these variables are always accounted for in published results.

Simulation

Conducting a process improvement simulation is difficult but not impossible . There exists some computer-based process modeling products such as WITNESS [34] and SIMUL8, [35] but most software and systems organizations probably won t spend the initial cost and training costs to purchase and use such packages. A more natural process simulation method is to simply conduct a walk-through or peer review of the proposed process. A few parameters you will want to factor into your process simulation and walkthrough are:

-

If there is a current process, make sure you have measurements on its effectiveness and value. If you do not have such data, you will not be able to determine if the new (replacement) or improved process is really an improvement.

-

Make sure you include in the simulation and walk-through people who know the history of the organization. Their experience can provide valuable input in terms of things that have been tried in the past and the results.

-

Make sure you include in the simulation and walk-through people who can or will be involved in the process or affected by it. Obtaining their input on the proposed process helps you get their support for implementing the process once it is ready to be implemented. Their input is also valuable for determining dependencies and constraints within the process.

Example

Let s go back to the situation in which you re trying to implement a project plan template in your organization. Using vicarious learning, you found a template on the Web that you think might work in your organization. Using walk-throughs to simulate the template in use, you (and other process people), stakeholders, and project managers and leads discuss the template and mentally walk it through the overall project planning process to understand how it needs to be modified to have the best chance of working in your organization. At a minimum, the questions that should be answered in these simulations are:

-

Who will use the template and what are their relevant skill levels? When will the template be used?

-

What are its current contents (e.g., sections)?

-

What content exists that is not applicable or not necessary in the organization? What content is it missing?

-

How will people use the template initially and how will they later update the resulting work product?

-

What training, instructions, procedures, or other work aids need to be provided in conjunction with the template so that people can use it?

-

If the work product (e.g., a project plan) that results from the template being used needs to be approved, how will this be done?

-

Which currently existing processes will be affected by the introduction of this template? How will they need to be changed to accommodate the template?

Simulation Pros

The benefits of simulation are:

-

Lower cost and faster relative to prototyping and online learning

-

It helps garner support for the process, idea, or work product prior to its implementation

Simulation Cons

The downside of simulations for processes, ideas, work products, or practices is:

-

No amount of walk-through, peer review, or discussion will ever find all the problems that can be revealed by prototyping or using something in a production environment.

-

It s very difficult to quantitatively measure or forecast the benefits or results of the new process or practice via simulation.

Prototyping

Second only to vicarious learning and benchmarking, prototyping (or rapid prototyping) is the most cost-effective and beneficial approach for an organization to learn process improvement; consider using the two approaches in conjunction for best results. If prototyping in process improvement were to have a motto, that motto would be limit the pain. With prototyping, you can find most of the things that are wrong with a process, practice, or work product ” things that annoy users or cause them pain ” in a small, subpopulation of the organization. You then have the opportunity to remove the problem before implementing the new item throughout the whole organization.

Prototyping in process improvement is nothing more than piloting or testing a process, practice, or work product in a limited, controlled environment. As with simulation, before prototyping a process idea, you ll first want to understand as much about the current or existing process as is practical so that you have a baseline against which you can compare the new process or work product.

Example

Following the example used in the previous subsections, let s look at how you would prototype the project plan template. The basic steps are:

-

Identify a subpopulation such as a project team to prototype the template. Ideally, the project team will be enthusiastic about trying out a new process solution and providing feedback. The project should also be typical of most of the projects in your organization.

-

Provide any initial training or orientation on the project plan template that is required.

-

Establish an easy-to-use, user-friendly communication channel by which the project personnel can provide usage feedback to the process people or function.

-

Make sure that feedback and suggestions for improvement are encouraged and rewarded or positively recognized. One of the most powerful things you can do in process improvement is to engender a culture in which people in the organization demonstrate their ownership of the processes and work products by constantly wanting to participate in their improvement.

-

Collect and analyze the feedback from the prototyping event and incorporate changes into the next version of the project plan template.

-

Based on criteria such as the amount of change or feedback received on the prototyped item, make a decision whether or not it needs to be piloted or tested again before general release.

-

Continue prototyping and revising the item until you and other stakeholders are content that it s ready to introduce into the organization.

Prototyping Pros

The benefits of prototyping are:

-

Lower cost and faster than online learning.

-

It helps you find significant problems with the proposed process or work product before being released to the general population, thus reducing the cost of resolving the problems. It limits the pain by having only a few enthusiastic processnauts bravely face the problems so that others won t have to.

-

It makes it relatively easy to understand and control the variables and dynamics that affect the success or failure of the process or work product.

-

It helps build support for the eventual process or work product by getting potential users involved in making the thing work the way they want.

| |

In today s world, corporate executives are all too easily influenced by tool, process, and initiative fads that they read about in a journal or have sold to them by a golfing partner. Without spending too much time understanding the problem, they turn to these solutions hoping for a silver bullet to fix the organization s problems. Once the tool, process, or initiative becomes the executive s pet project, no one lower in the hierarchy is going to tell him or her that the solution is causing more problems than it s fixing. As a change agent in your organization, you will forever win the support, loyalty, and admiration of employees by prototyping or piloting change, thus limiting the pain on the larger organization.

| |

Prototyping Cons

The negatives associated with prototyping processes, ideas, work products, or practices are:

-

Prototyping a process or work product won t be able to find all of its problems. (However, you ll find 80 percent of the problems with 20 percent of the effort.)

-

Prototyping, especially in one iteration or cycle, can yield a false positive or a false negative. The results could lead you to believe that the success (or failure) of the change will be the same when introduced into the larger organization, but there s no guarantee that this is true. You can limit your risk by conducting more than one prototype cycle.

Online Learning

Online learning is taking a change, such as a new or improved process, work product, or tool, and launching it; that is, introducing it into real production in the organization. In mature organizations (regardless of the appraised CMMI level), new technology, processes, and work products are not put into production until after they are thoroughly evaluated or tested. Sadly, in this regard, most organizations are not mature. Not enough warnings can be given about the evils of introducing change without the three Ps ” planning, preparation, and prototyping ” so if you have any say in the matter, just don t let it happen.

[31] The quarterly Maturity Profile published by SEI on its Web site shows the number of organizations that have reported their CMM assessment results. The data is parsed in numerous ways including by industry sector (SIC), geographical area, and organization size .

[32] Gartner Group definition for best practices.

[33] West, Michael, Project Management Best Practices, delivered to the California Management Accountants (CMA) in Solvang, CA on August 17, 2001.

[34] WITNESS is a process simulation product of Lanner Corporation. For more information, go to http://www.lanner.com/corporate/.

[35] SIMUL8 is a process simulation product of SIMUL8 Corporation. For more information, go to http://www.simul8.com/.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 110