Chapter 15: Protecting Your Data and Your Privacy

|

|

The issue is privacy. Why is the decision by a woman to sleep with a man she has just met in a bar a private one, and the decision to sleep with the same man for $100 subject to criminal penalties?

--ANNA QUINDLENDESPITE THE LIP SERVICE PAID TO NOBLE-SOUNDING PRINCIPLES LIKE HUMAN RIGHTS AND PERSONAL FREEDOM, MOST GOVERNMENTS HAVE NO QUALMS VIOLATING EITHER PRINCIPLE FOR POLITICAL EXPEDIENCY AND SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC PROFIT. Because governments are less interested in protecting the rights of individuals than they are in protecting their own members, the only person who has the most interest in protecting your individual rights is you.

PROTECTING YOUR DATA

Whether you store confidential business secrets on your computer, personal notes, incriminating email, financial records, or just plain ordinary information that you don't want other people to see, you have the right to keep your data private. Of course, having the right to privacy is one thing—exercising that right can be a completely different problem.

Besides blocking physical access to your computer (see Chapter 20), you can password-protect your data, encrypt it, or hide it and hope no one knows where to find it. Better yet, combine several of these methods and you can make access to your data as difficult as possible for someone other than yourself.

Password protection

Passwords are only as good as their length and complexity. Still, if you choose a good one, you can block access to most would-be data thieves. Rather than rely on the weak password protection available in screensavers, use a dedicated password-protection program instead. Not only can a dedicated password-protection program block access, but it can prevent someone from rebooting your computer to circumvent your password protection.

Windows users can try Posum's Workstation Lock (http://posum.com), which can password protect your computer; Password Protection System (http://www.necrocosm.com/ppsplus/index.html), which can password protect individual files, such as data files and actual programs; or WinLock (http://www.crystaloffice.com), which restricts access to certain programs to people with the correct password.

Encrypting your data

Password-protection programs can restrict access, but don't rely on them to keep your data safe. For further protection, use encryption to scramble your data beyond recognition. Of course, encryption is only as good as your password—if someone steals your password, encryption will be as useless as a bank vault without a lock.

Besides choosing a weak password, another flaw is choosing a weak encryption algorithm. Encryption algorithms define how the data is scrambled, and not all encryption algorithms are alike.

Proprietary encryption algorithms are often the worst, since hiding the way an algorithm works (known as "security by obscurity") won't disguise the fact that it scrambles data in a predictable manner that can be used to crack the encryption. Any program that claims their proprietary encryption algorithm is secure most likely doesn't know anything about encryption in the first place.

The better encryption programs use algorithms that have been published worldwide and survived the scrutiny of security experts over the years. That doesn't mean that they don't have any flaws—it's just that no one has found any weakness yet—or the NSA has and isn't telling. (Studying an encryption algorithm can reveal how that algorithm encrypts data, but it won't necessarily show you how to crack it.)

Some of the more popular encryption algorithms include the Data Encryption Standard (DES), International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA), Rivest Cipher #6 (RC6) (http://www.rsasecurity.com/rsalabs/rc6/index.html), Blowfish and Twofish (http://www.counterpane.com/labs.html), and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) (http://csrc.nist.gov/encryption/aes).

Encryption scrambles your data, but passwords protect it. In the world of encryption, two types of password methods have emerged: private-key encryption and public-key encryption.

Private-key encryption uses a single password to encrypt and decrypt data, which means that if you lose or forget your password, you can't get your data, and anyone who discovers your password can decrypt your files. Even more troublesome is that if you want to send someone an encrypted file, you have to figure out a safe way to send them the password first so they can decrypt the file when they receive it.

To overcome the flaws of private-key encryption, computer scientists developed public-key encryption, which gives you two passwords: a private and a public key. The private key is (hopefully) known only to you. The public key can be given freely to anyone.

You can use your private key to encrypt a file, and anyone with your public key can decrypt it. If someone wants to send you data, they have to encrypt it using your public key. Then that encrypted file can only be decrypted using your private key.

One of the most popular encryption programs is Pretty Good Privacy (http://www.pgp.com and http://www.pgpi.com), written by Phil Zimmermann, who is generally credited with making public-key encryption widely available by releasing the source code to his Pretty Good Privacy program (PGP) over the Internet. When the source code managed to find its way to other countries, the U.S. government began a fruitless five-year criminal investigation to determine whether Phil had broken any laws that classified encryption technology as a "munition." Eventually the government dropped the charges after realizing they didn't have a case and popular opinion was against them.

Similar to PGP is a free and open source version dubbed GNU Privacy Guard (http://www.gnupg.org). Besides PGP, there is other encryption software:

| Kryptel | http://inv.co.nz |

| PC-Encrypt | http://www.pc-encrypt.com |

| Absolute Security | http://www.pepsoft.com |

| CryptoForge | http://www.cryptoforge.com |

To read a free monthly newsletter covering encryption, visit the Crypto-Gram Newsletter (http://www.counterpane.com/crypto-gram.html) written by Bruce Schneier, author of Applied Cryptography. Or, to discuss encryption, visit one of these newsgroups: alt.security, alt.security.pgp, comp.security.misc, or comp.security. pgp.discuss.

Defeating encryption

The simplest way to defeat encryption is to steal the encryption password. Failing that, you can try a brute-force attack, which essentially involves trying every possible password permutation until you eventually find the correct one. Brute-force can defeat every encryption algorithm, but the stronger encryption algorithms have so many possible combinations that to exhaustively test for each one would take even the fastest computer millions of years, so in practice the encryption is secure.

The faster and more powerful computers get, the easier it will be for brute-force attacks to pry open weaker encryption algorithms. On June 17, 1997, a team of college students used a brute-force attack to crack a DES-encrypted file in a $10,000 contest sponsored by the RSA Security. This "cracking" program, code-named DESCHALL (http://www.interhack.net/projects/deschall), was distributed and downloaded over the Internet so volunteers could link thousands of computers together and attack the problem simultaneously. Now, if a team of college students can crack DES using ordinary computer equipment, think what governments can do with their higher budgets and specialized hardware. The moral of this story is that if the strongest encryption algorithm a program offers is DES, look elsewhere. Triple-DES (a derivative of the DES encryption standard) is stronger than ordinary DES, although many encryption programs prefer the newer AES encryption standard.

Hiding files on your hard disk

One problem with encryption is that it can alert someone that you're hiding something important. Because no form of encryption can be 100 percent secure (someone can always steal the password or crack the encryption method), you might try a trickier method: Hide your sensitive files. After all, you can't steal what you can't find.

To do so, visit PC-Magic Software (http://www.pc-magic.com) and download their Magic Folders or Encrypted Magic Folders program. Both programs let you make entire directories invisible so a thief won't even know they exist. Encrypted Magic Folders hides and encrypts your file, so even if someone finds the directory, they won't be able to peek at its contents or copy any of its files without the proper password.

Similar programs that can hide and encrypt your hidden folders include the following:

| bProtected | http://www.clasys.com |

| Hide Folders | http://www.fspro.net |

| WinDefender | http://www.rtsecurity.com/products/windefender |

Encryption in pictures

Since few people encrypt their email, those who do use encryption immediately draw attention to themselves. If you want to use encryption while looking as if you aren't, use steganography, a term derived from the Greek words steganos (covered or secret) and graphy (writing or drawing), literally meaning "covered writing." Steganography is the science of hiding information in an apparently harmless medium, such as a picture or a sound file.

For example, suppose government agents decide to snare every email message sent to and from a particular website. With unencrypted email, spying computers could easily search for keywords like "nuclear," "missile," "nerve gas," or "bomb" and store copies of these messages for further analysis. If you encrypt your email, they can just as easily grab copies of your encrypted messages and use their supercomputers to crack them open later.

But if you use steganography, you can send seemingly innocent graphic files of famous paintings, antique cars, or bikini-clad models that actually contain hidden messages inside. These ordinary files could easily contain underground newsletters, censored information, or simply ordinary text that you want to keep private. If someone intercepts your email, they'll see only a picture. Unless a snoop is certain that the picture contains hidden messages, he'll most likely ignore it.

Steganography programs break up your data (either text or encrypted text) and bury it within a graphics or sound file, such as a GIF or WAV file. In the process, the steganography program slightly corrupts the graphic or sound file, so the more data you try to hide, the greater the degradation.

You can use two techniques to prevent total degradation (which would flag the fact that a graphic or sound file contains hidden information). First, use black-and-white instead of color graphic files, because slight degradation in a black-and-white graphic isn't as noticeable as it is in color graphics. Second, store small files in multiple graphic or sound files rather than cramming all the information into a single graphic or sound file.

To toy around with steganography programs and learn more about this relatively obscure branch of encryption, visit the StegoArchive website at http://steganography.tripod.com/stego.html and look for popular steganography programs such as S-Tools, Invisible Secrets, or Hide and Seek.

You might also like to visit Stego Online (http://www.stego.com), download the free Java source code, and practice encrypting text files within GIF files on your own hard disk. If you're serious about encrypting your data and disguising that fact, browse through the steganography newsgroup at alt.steganography.

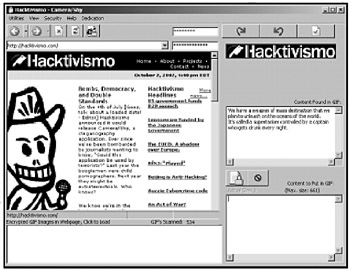

In an effort to help people communicate against their government's wishes, a group of hackers from the Cult of the Dead Cow developed a steganography tool called Camera/Shy (http://hacktivismo.com/projects). Once you hide a message inside a GIF image using Camera/Shy, you can post that GIF image on a web page. Anyone with a copy of Camera/Shy and the right password can browse your web page and display the hidden messages in each GIF image (see Figure 15-1).

Figure 15-1: The Camera/Shy program can hide messages in GIF images on a web page so other people can read them.

Although steganography might seem like the perfect way to communicate in secret, it can be detected. Two programs, Stegdetect (http://www.outguess.org) and Stego Watch (http://www.wetstonetech.com) can scan graphic, sound, and video files to look for hidden messages. While they may not necessarily be able to read any hidden messages buried inside a graphic image, both programs can alert someone that a hidden message exists. Depending on what part of the world you live in, that could cause the authorities to watch you more closely or give them a "reason" to make you disappear in the middle of the night.

To learn more about encryption, visit Cryptography A-Z (http://www.ssh.fi/tech/crypto) to find links to free encryption software, companies selling encryption packages, and universities offering encryption course materials, and as much about encryption as you care to learn, provided (of course) that the government hasn't already confiscated your computer.

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 215