DEFINITIONS

We can define an ethnic group as a social group that has a common cultural tradition, common history, and common sense of identity and which exists as a subgroup in a larger society. By implication , the members of an ethnic group differ with regard to certain cultural characteristics from other members of their broader society. The ethnic group may have its own language, religion, and other distinctive cultural customs .

Extremely important to the members of an ethnic group is their (positive) feeling of identity as a traditionally distinct social group. The term is usually, but not always, applied to minority groups. Ethnic groups should not be confused with, or taken as synonymous with, racial groups, although it is possible for an ethnic group to be a racial group as well (for example, African Americans). The concept of ethnicity is a complex process with multiple stages and multiple outcomes . It begins with contact, when newcomer ethnic groups arrive but try to maintain their old culture and identity - perhaps as a means of survival, or a means of living their lives in a familiar way because that is what they are comfortable with. They may seek out areas to live and work where they can develop a network of friends with the same value systems.

Through acculturation ethnic identities emerge amid greater exposure to the larger society and culture. Adaptation sees the group trying to maintain its ethnic identity but slowly giving way to the dominant culture. The decreasing number of foreign-born members of the group are accommodated and gradually integrated, finally being assimilated into "mainstream" society and culture. Ethnically based cultural traditions manifest in daily life, but especially on significant occasions such as weddings, births, religious festivals, and deaths. Many ethnic groups are financially disadvantaged and/or suffer other forms of prejudice.

Categorizing individuals in societies can be achieved in a number of ways ranging from a subjective approach (where individuals are asked to decide their own groupings) to more objective approaches based on factors such as lifestyle, income, etc. The aim of the traditional marketing approach is to model the structure of different classes or groups because these are ways of determining (predicting) buyer behavior. In practice, however, marketing place models are more complex and, for some businesses and services, social class or income alone may be a more important discriminator than ethnicity. For others, such as low-interest loans for example, ethnic grouping may be more important, where the lender benefits from shared equity growth or insurance premium cover.

The family is a vital frame of reference, and especially so with many ethnic groups. This may persist even after individuals have grown up and left the parental home. Accordingly, marketers use life cycle stages as a means of fine tuning their marketing strategies.

Commonly recognised American ethnic groups include American Indians, Hispanics/Latinos, Chinese, African Americans, and European Americans. Other examples from the American ethnic experience would include Italians, Jews, the Irish, Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Poles, etc. In some cases, ethnicity involves merely a loose group identity with little or no cultural tradition in common. This is often the case with many Irish and German Americans. In contrast, some ethnic groups are coherent subcultures with a shared language and strong body of tradition.

Because several terms are used in many different ways in different situations, it is not entirely clear how "inter-ethnic" differs from "cultural difference." Ethnicity is defined by various authors with various designations: a "source of cultural meaning," a "principle for social differentiation," an act of "communicating cultural distinctiveness ," a "property of a social formation," and an "aspect of interaction." However, it is commonly agreed that ethnicity is observable (through what we call the "outer layer of the onion" cultural model).

The concept of ethnicity has proven useful to domestic government agencies and international organizations trying to assist ethnic minorities in multiethnic societies to advance themselves . Rather than treating the inhabitants of a developing country as culturally homogenous, for instance, most international aid agencies now try to take into account the values, institutions, and customs of various ethnic groups, targeting relief or aid to their particular needs.

The ways people show that they are proud of their ethnic group include:

-

behaving in a distinctive manner,

-

living near one another,

-

attending special functions (e.g., particular sports events),

-

performing traditional rituals (e.g., weddings, religious festivals), and

-

wearing distinctive clothing.

Ethnicity is in many contexts the single most important criterion for collective social distinctions in daily life; ethnic distinctions are rooted in perceptions of differences between lifestyles. However, even more important (and usually overlooked) is that ethnic groups often share the same meaning as their forefathers in the inner layer of culture. It is all too easy to notice the outer layers and forget that we have to respect not only these observable differences, but also everyone's right to interpret the world in the way that they choose. As with national cultures, the seven dimensional model of culture helps us to understand these deeper differences.

Consider Hispanic Americans as an example. Fifteen percent of the US population will be of Hispanic origin by 2007. Many Hispanic Americans are the descendants of Mexican people who lived in the Southwest when it became part of the United States. Almost all other Hispanic Americans or their ancestors migrated to the United States from Latin America. The three largest Hispanic groups in the United States are Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans. As a group, Hispanic Americans represent a mixture of several ethnic backgrounds, including European, American Indian, and African. At THT we have found in our research that those Hispanic Americans who have completed our cross-cultural diagnostic instruments have a more similar orientation on these seven dimensions to people from their areas of origin (such as Latin America) than they do to typical Caucasian Americans.

But what does this mean for the marketing manager? Looking at the demographics in both Europe and North America, we soon realize that we don't have to leave our own countries to meet the similar dilemmas that international marketing managers are facing . If we just consider the Netherlands, for example, we can observe that its major cities, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague, are becoming truly multicultural. By the year 2020 more than 50 percent of all residents of these cities will have no Dutch roots whatsoever. And 2 million of the predicted 18 million will come from non-western cultural backgrounds, in particular the Moroccans, Turks, Surinamese, and Antilleans. In the UK census records show more than one million people of Indian heritage and over 300,000 with a Pakistani background. In the city of Leicester, where over a quarter of the population is Asian, a large number of retailers cater for the particular tastes of this ethnic minority. This can even extend to bureaux for arranged marriages, which do not form part of the society of the host culture. In Germany there are more than three million Muslims and in France the prominence of the ultra -right-wing politician le Pen shows that these changes need to be taken very seriously.

Furthermore, the composition of this ethnic diversity continues to shift. The US 1990 census counted 30 million African Americans, an increase of 13 percent over ten years . Asian Americans numbered 7.3 million, double the figure for 1980. Hispanics numbered 22.4 million, a 53 percent increase that put Latinos on course to becoming the nation's largest single ethnic group in a little more than a decade - and in 2004 the US census bureau announced that for the first time in history there would indeed be more US Americans with a Hispanic background than African Americans. President Bush's policy of allowing illegal immigrants to naturalize would accelerate this further. Among Hispanic residents, 70 percent were born abroad and an equal percentage speaks Spanish at home.

The national and international economic effects of these global trends are phenomenal. They are not only causing a change in methods , types, and categories of production because of a changing and diverse workforce, but also a need for the marketing of products and services:

In many respects, immigrants are the ideal consumers. The "need-everything" generation arrives without refrigerator, stove , washing machine, television, or automobile. They buy what they can afford, but as they adapt and move up the economic scale, they upgrade these items so that both the need and frequency of purchase is greater than in the general marketplace . Moreover, there is often an overcompensation factor: they tend to make up for all the years in which acquisition of such an array of material goods would have been unthinkable. (Brandweek, 2001)

Thus it is most important for marketers to recognise that when members of any such ethnic group acquire the same disposable income as members of the dominant culture, they don't simply abandon their heritage and consume the same things or at the same rate as members of the host culture. Among the young, upwardly mobile Punjabi population in the US or young Moroccans in the Netherlands, for example, the accumulation of high-status possessions such as cars and designer clothing is a key marker, signifying successful assimilation, signs that they fit in. They also help as a bridge between the more traditional culture of their parents and their need to assimilate into the new society.

Annual buying power of minority customers exceeds $1 trillion and US companies now spend $2 billion each year on advertising specifically designed to attract and engage these "New American" consumers. In the Netherlands, despite enormous economic possibilities - the buying power of "New Dutch" citizens is some 20 billion euros - the literature on ethnic marketing is scarce and of a very low quality in that it is not based on data and is not conceptualized into any robust explanatory framework. Of course, this is typical of any newly developing field; it doesn't outgrow the awareness phase. Any advice that is given is based on how to segment the market differently: that is, by ethnic characteristics. This shows that Moroccans are keen to buy expensive clothing, while Turks invest in audiovisual equipment and Antilleans seek out "exotic" food.

In societies that are very segmented, where ethnic groups have clearly differentiated value orientations, a multiethnic strategy makes lots of sense. It could even be seen as a good remedy against the universal mass-consumption societies that many have become, as Halter comments:

Though a crucial component of the rationale for the creation of ethnic pride groups and related culture-specific practices may be to protest against the ills of consumer society, the new ethnics demonstrate that they are nonetheless deeply tied to consumerist practices...In effect, the market serves to foster greater awareness of ethnic identity, offers immediate possibilities for cultural participation and can even act as an agent of change in that process. (Halter, 2002)

The response is that, increasingly, advertising agencies such as those in the US and in Europe (to some extent) specialize to effectively focus on one of the primary New American umbrella groups - Hispanics, Asians, or African Americans - or New European groups - North Africans, Central Europeans, and citizens of former colonies.

The more sophisticated target marketers understand the limitations of too wide or too loose definitions for any groupings or clusters. For example, a crucial component of training marketing staff (in the US) is to develop an awareness of the complex intra-ethnic variations among both the Hispanic and Asian segments and to pass this knowledge on to their clients . Although both Cubans and Mexicans are classified as Hispanic by virtue of their common language, in reality their socio-cultural histories and patterns of settlement in the US are quite divergent and demand differentiated marketing approaches.

Multicultural marketing experts have proliferated and act as their companies' in-house ethnographers, learning and responding to the cultural nuances of their audiences. At the same time, ethnicity in itself is becoming increasingly optional and malleable, as individuals choose to take on certain identifying aspects of their cultural group while rejecting others.

The challenge for members of ethnic groups is to reconcile their own cultural heritage and what they prefer to retain with the norms and values and opportunities of adapting to the dominant society/culture in which they live. So we should consider two interesting questions that can be the starting point for sophisticated approaches to marketing:

-

How does commercialism both enhance and make a commodity of ethnic identification?

-

How do you market to groups that are not segmented but have a high degree of interaction amongst ethnic groups?

In marketing, the dilemma for considering ethnic issues is quickly apparent. On the one hand, society is faced with two dramatic and opposing forces. First, there is the advancement in communication and transportation that has given rise to a global economy, potentially moving people towards a homogenized identity. However, there is an opposing force to this one-world identity, as groups become more aware of themselves or group identity on the basis of their ethnic background (Costa and Bamossy, 1995). Media advertising has traditionally assumed that a white ethnic majority and other ethnic minorities can be reached simultaneously . Thus ads for mass audiences have tended to use white models exclusively, which is consistent with the melting-pot theory. It also leads to the assumption that ethnic minorities would gradually take on a white ethnic identity - or at least the purchasing decisions of whites (Kinra, 1997).

On the contrary, researchers have also argued that the trend is towards greater ethnic and cultural diversity. Culturally distinct segments cannot all be successfully targeted using the same marketing and advertising strategies that succeeded when society was a uniform, western market (Rossman, 1994; Berman, 1997; Kim and Kang, 2001).

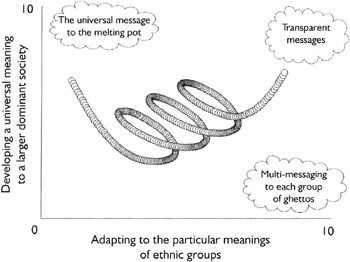

The dilemma is represented in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: The multi- versus mono-ethnic society dilemma

Another approach is that which seeks to design promotions that find a "zone of commonality " centering on similarities rather than differences. Instead of the traditional single ethnic message, there are practitioners who develop crossover advertising in a process they call "transcreation" (Brandweek, 2001).

Berry (1990) identifies four possible models of acculturation:

-

Integration: individuals adopt some of the host culture while simultaneously maintaining their own culture.

-

Separation: consumers refuse to integrate into the host culture.

-

Assimilation: consumers adopt the host culture and forget their original culture over time.

-

Marginalization: consumers feel rejected by the host culture but do not want to maintain their original culture.

Obviously many marketing problems and suggestions for reconciliation across national boundaries apply at home as well, but some are quite specific. Different types of clients representing different cultures enter the same bank. Media channels are quite similar but aimed at a multicultural clientele.

Mono-Ethnic Marketing: the Melting Pot

An important issue is whether ethnic minorities will ultimately accept the culture of the host country, or if they will retain their own. It could be argued that if ethnic minority groups become completely assimilated then ethnicity as a variable would cease to be important and marketing discourse on the topic redundant. The whole acculturation issue is more complex and there are arguments for both approaches.

A primary reason that has been offered for a lack of ethnically diverse faces in marketing stimuli is a fear of negative attitudes from the majority white population or a so-called "white backlash ." So despite the growth of ethnic minority groups in many societies, most advertisers have failed to reflect today's realities and have tended towards excluding or minimizing ethnic minorities from their advertising mix (Dunn, 1992; Marshall, 1997).

Some studies with cross-ethnic orientations, however, found that using ethnic minority actors and models raised the attitudes and purchase intentions of audiences of the same ethnicity without decreasing the attitudes and purchase intentions of the majority ethnic group (Lee et al., 2002). Further, the ethnicity of the advertising model had no significant influence on the ad, brand, attitudes, and the purchase intentions of the white majority group. While Asians showed more positive attitudes and purchase intentions towards ads that featured Asian models, the white majority's attitudes and purchase intentions were not significantly influenced by the ethnicity of the models. Thus marketers and media planners, by simply varying the ethnicity of the models featured in promotional materials, may improve their rapport with their target minority groups without endangering their position with the majority group. This opened the way to a forceful multiethnic marketing approach. Simple tokenism, whereby stratified ethnic representation is sprinkled in a mixed group, however, needs to be avoided.

Multiethnic Marketing Approach

More and more consumers themselves are expressing culturally distinctive desires, needs, and wants in their shopping habits, and these demands, as well as patterns of product loyalty, have prompted consulting, research, and communications firms to begin specializing in multiethnic niche marketing.

Some believe that the most effective way is to take these ethnicities seriously with significant consequences for the marketer. Thus Rosen believes:

Each population must be communicated with on its own terms, and with an open -minded approach to the many sensitivities and possibilities each marketplace presents . The imperative for marketers is to address each ethnic group, and the many subgroups within them, in ways they find relevant and motivating. (Rosen, 1997)

The power of ethnicity as a target variable is demonstrated implicitly by its frequent use in advertising underpinned by a wealth of prior research, documenting positive consumer responses to advertising that features similar-ethnicity actors or spokespeople.

Much attention has been given to the effectiveness of ads for different ethnic groups. For example, recent research has found that both identification and feeling similar to an ethnic spokesperson and the perception of being targeted by an advertisement are important motivators of consumer response to ethnic advertising. Both inherently involve some recognition of the match between the endorser's characteristics and the consumer's characteristics. As such, factors that increase ethnic self-awareness should increase the likelihood that a consumer will feel similar (or dissimilar) to an ethnic endorser and thereby feel targeted (or not) by an advertisement that features that ethnic endorser (Forehand and Deshpande, 2001). This type of self-referencing occurs when consumers process information by relating it to some aspect of themselves, such as their past experiences. One of the effects of self-referencing is the generation of favorable cognitive responses, more positive attitudes towards the ad, the advertising model, and higher purchase intentions (Lee et al., 2002).

| |

Patients of cosmetic surgeons often have some idealized image such as Grace Kelly or Liz Hurley in their minds. Surgeons have developed reference formulae based on these stereotypical ideals and thereby define standard target measurement ratios such as the length of the nose compared to its width, or cheekbone prominence. However such standards are being revised and some surgeons need different ones because what is "beautiful" is different for different ethnic groups. White girls are more likely to base their ideal on a Barbie-doll-like figure. Black girls are more likely to base their ideal on what they perceive black men value in women, including fuller hips and larger thighs.

Increasingly surgeons are being asked by patients to make them more appealing to all men, from any ethnic background. A major reconciliation task for the surgeon! [1]

| |

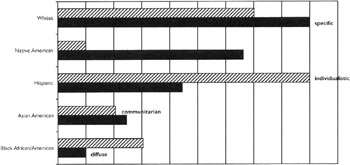

There are quite succinct differences within the US database at THT. If we look at the score on specific versus diffuse orientation across American ethnicity in our database we see significant variations, illustrated in Figure 7.2. Obviously this (as well as differences across other cultural dimensions) should be taken into account in the way advertising should be commissioned to different ethnic groups in the US.

Figure 7.2: Variation of specific-diffuse and individualistic orientations amongst several US ethnic groups

This is illustrated by the way that the more diffuse and communitarian African American women have been approached quite differently by P&G.

| |

Cincinnati-based Procter & Gamble consistently tries new marketing approaches for its products even when it has a leadership position in the product category. Among feminine hygiene products, for example, P&G's Tampax is the leading brand, and the company has promoted it primarily through. magazine and television advertising and through alliances with a number of women-oriented groups, such as the Women's Sports Foundation.

However P&G sought to maintain and support the brand's position among African American women by a special event marketing program aimed at that niche. The "Total You" tour combined health and fitness information with discussions of current issues of interest to black women through panel discussions with leading health experts, celebrity appearances , an expo, and other opportunities to participate. A "Total Care Tent" offered free massages and manicures. "The breakthrough is presenting these topics is a sisterly environment," says Anne Sempowski, a multicultural brand manager for P&G, noting that African American women don't have that many opportunities to gather and communicate in a group. "It's not just about providing information. We want it to be a total experience where African American women can come, together and learn about topics that are important to them."

Meanwhile, the company has the chance to reinforce its brand message that "Tampax is safe, comfortable, and frees a woman up to do activities she normally might not do during her period," Sempowski notes. [2]

| |

Another case of multiethnic marketing is the approach that we can learn from South Africa. During apartheid, there was a very strict separation between black and white media. Producers could easily communicate to white and black customers separately. Gaby Siera describes how the same commercial was shot twice so that it could later be distributed through both white- and black-oriented media:

A well-known brand of soap segmented its market into a white and a black target group. The commercial aiming at the white target group shows a white woman lying in a bath full of foam and singing. Her husband walks into the bathroom. She is startled and stops singing, "Feel good and feel free with this soap!" In the commercial for the black consumers we also see a singing woman - a black woman in this case. However, it is not her husband who walks into the bathroom, but her child. The woman is not startled; on the contrary, she goes on singing cheerfully, along with her child. (Siera, 2000)

The reaction of a black staff member at the ad agency was scathing and was critical of "a poor and preposterous commercial suggesting that among black people it's prohibited to enter the bathroom when one's wife is bathing." Belittling as that is, it suggests that different commercials should be made for different groups. A white staff member spoke well of it: "It takes into consideration cultural differences of the two target groups." This is a typical example of a particularistic, multi-local approach.

After the fall of apartheid a variety of new approaches were needed in order to address the new and evolving marketplace. The separation of media for different ethnic audiences gradually disappeared so that multicultural groups saw identical commercials through one and the same medium. This led to some different solutions.

According to Siera's ethnographic research, many of the multiracial advertisements were still containing messages that were non-interactive. It was observed that advertising with no interactions, with whites and blacks still separated, was most used for family situations, showing black and white families in turn , or they were shown on separate pages, with blacks and whites never interacting across groups. As such these advertisements seem to avoid any politically risky activities.

This tendency for ethnic groups to hold fast to their roots presents both a threat and an opportunity. The opportunity in multiethnic marketing is to create a strong and lasting bond with ethnic consumers by reaching out to them in their communities and speaking to them in their native languages and with awareness of their cultural heritage. Ultimately this will express the benefits of your products and services in terms of their own value orientations. Marketing messages that fail to address consumers in terms of their own thinking and orientations are likely to miss their targets. Another, more serious, danger is that these messages can be offensive if they fail to take into account ethnic and religious sensibilities or sensitivities.

Overall there is considerable disagreement surrounding the discipline of ethnic marketing. Some protagonists believe in carefully targeted messages to each ethnic group or subgroup. Others insist on one effort that reaches down to core human values. Although ethnic values may differ, the increase of interactions between groups cannot be denied . Here a more sophisticated approach is called for, one that reconciles and creates a translucent message through what we can describe as transcreation.

[1] Source: Adapted from Merrel (1994.)

[2] Source: Sharoff (2001).

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 82