14.1. Wireless Networking Standards Current wireless networking components use one or more of the following standards, which are referred to collectively as standards:

802.11b -

The 802.11b specification was released in mid-1999, and devices based upon it soon flooded the market. 802.11b supports a maximum data rate of 11 Mb/s, comparable to 10BaseT Ethernet, and has typical real-world throughput of about 5 Mb/s. 802.11b uses the unlicensed 2.4 GHz spectrum, which means that it is subject to interference from microwave ovens, cordless phones, Bluetooth adapters and gadgets, and other devices that share the 2.4 GHz spectrum. 802.11b is functionally obsolete, because components that use faster standards and have much better security are now available at reasonable cost. Millions of 802.11b adapters remain in use, primarily as embedded or PC Card adapters in notebook computers.

802.11a -

The 802.11a standard was released concurrently with 802.11b, but 802.11a was slower to catch on, because it originally required an FCC license and because 802.11a components were significantly more expensive than 802.11b components. 802.11a supports a maximum data rate of 54 Mb/s, and has typical real-world throughput of about 25 Mb/s. It uses a portion of the 5 GHz spectrum that was formerly licensed, which limited interference from other devices. Unlike the wild-and-woolly 2.4 GHz spectrum, where anyone at all could play without permission, the 5 GHz spectrum was tightly regulated to avoid interference. Although that portion of the spectrum is now unlicensed, it remains relatively uncluttered. The real downside of 802.11a is that a 5 GHz signal has shorter range and is more easily obstructed than a 2.4 GHz signal. However, 802.11a, which for a time seemed moribund, is seeing a renaissance that is primarily driven by home users who have found that the 5 GHz spectrum used by 802.11a is much more reliable for such tasks as streaming video wirelessly.

802.11g -

The most recent wireless standard is 802.11g, which combines the best features of 802.11a and 802.11b. Like 802.11b, 802.11g works in the 2.4 GHz spectrum, which means it has good range but is subject to interference from other 2.4 GHz devices (such as cordless telephones). Because they use the same frequencies, 802.11b components can communicate with 802.11g components, and vice versa. Like 802.11a, 802.11g supports a maximum data rate of 54 Mb/s, and has typical real-world bandwidth of about 25 Mb/s. In the absence of interference, that is sufficient to support real-time streaming video, which 802.11b cannot. 802.11g components are now inexpensive, and have made 802.11b obsolete. | MIXING AND MATCHING WIRELESS COMPONENTS | In theory, 802.11b and 802.11g components are standards-based, so components from different manufacturers should interoperate. In practice, that is largely true, although minor differences in how standards are implemented can cause conflicts. In particular, some high-end 802.11b/802.11g components include proprietary extensions for security, faster performance, and similar purposes. Those components do generally interoperate with components from other vendors, but only on a "least common denominator" basisthat is, using only the standard 802.11 features. The best way to ensure that your wireless network operates with minimal problems is to buy all of your wireless components from the same vendor. |

"802.108g" -

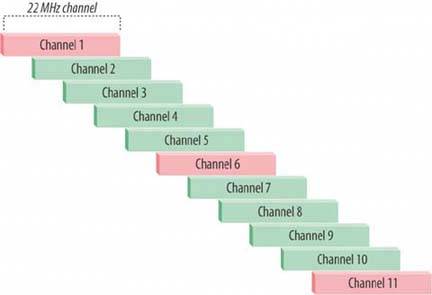

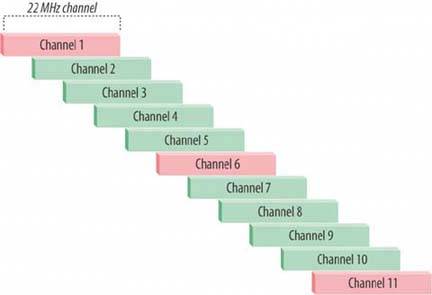

Several manufacturers, including D-Link and NetGear, produce wireless components that claim to provide 108 Mb/s bandwidth. In fact they do, but only by "cheating" on the 802.11g specification. Such components, colloquially called "802.108g" devices, work as advertised, but using them may cause conflicts with 802.11g-compliant devices operating in the same vicinity. The problem is this: 802.11g defines 11 channels (13 in Europe), each with 22 MHz of bandwidth. Each 22 MHz channel can support the full 54 Mb/s bandwidth of 802.11g. But these channels overlap, as shown in Figure 14-1. Three of the channels1, 6, and 11are completely non-overlapping, which means that three 802.11g-compliant wireless networks in the same vicinityone assigned to each of the three non-overlapping channelscan share the 2.4 GHz spectrum without conflicts. Alternatively, two 802.11g-compliant networks can be assigned to two channels that do not overlap each other, for example, Channels 2 and 8. Unfortunately, the design of 802.108g devices is such that they claim not just 2/3 of the available spectrum, but all of it. Rather than use the top 2/3 or the bottom 2/3 of the range, current 802.108g devices use the middle 2/3, leaving only small spectrum segments at either end of the range unused. Because the spectrum segments left unused by 802.108g are not a full channel wide, no other 2.4 GHz 802.11 devices can operate without interference in the vicinity of an 802.108g device that is operating in full-speed 108 Mb/s mode. Figure 14-1. 802.11g channels

|