THE RED BEAD EXPERIMENT

Recall that several of Deming's 14 points concern the role of management in helping workers to do a better job. Deming believed that it is not management's role simply to exhort workers to do a better job. Management needs to change a system that prevents workers from performing up to standards. To illustrate this concept, Deming often used the following red bead experiment. It illustrates clearly that in a system subject only to common-cause variation, some workers are bound to be the best on some days and the worst on others, for no particular reasons (such as slacking off or working harder). It also illustrates how all workers can fail to live up to standards, through no fault of their own, if the system is not designed correctly.

The experiment is very simple. There is a large container of beads, 20% of which are red and 80% of which are white. Several people from the audience are asked to play the role of workers, and others from the audience are asked to help out as inspectors. Each of the workers gets a paddle with 50 holes; each hole can hold a single bead. The rules of the game are that each worker must put his or her paddle into the container and pull out exactly 50 beads. Each such draw corresponds to 1 day's production quantity; that is, each worker "produces" exactly 50 beads per day. Workers are also told that red beads correspond to defectives. Each person's job is to produce no more than two defectives per day; their continued employment depends on doing so. The inspectors then count the number of red beads for each worker for each day's production and tally the results for all to see.

Let's say the workers' names are Cary, Timothy, Stephen, and Christine. Several things about the experiment are fairly obvious. First, the mechanics of the process make it impossible for workers to fish for all white beads. Therefore, every worker gets a random sample of 50 red and white beads on each draw from the container. Some days Cary will, totally by luck, get the most red beads, and other days, he will get the fewest red beads. The same applies for the other workers. Certainly , there is no reason to reprimand Cary in the first case or reward him in the second, but Deming says that this is exactly what occurs in many job settings.

Second, the experiment is stacked against the workers. It is impossible for them, on most days, to draw two or fewer red beads. On average, each draw will result in 20%, or 10, red beads. For them to do their job as instructed, the system must change. For example, management could remove many of the red beads from the container. Even though all of this was obvious to the "workers" in Deming's experiments, it is interesting that many of them nevertheless tried their best to perform as instructed and that many were genuinely frustrated when they continued to draw too many red beads.

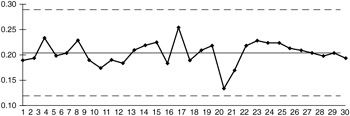

We can illustrate the red bead experiment with an Excel simulation, using the binomial function based on 50 trials. After running the simulation, we find that the daily production, at least for this simulation, of red beads varies randomly around 0.2. At this stage, we can also do a p chart (see Figure 6.12).

Figure 6.12: A p chart for the red bead experiment.

The p chart shows a process well in control. In particular, it shows how the daily proportion of red beads varies randomly around 0.2. Of course, this doesn't mean that the workers are producing what management wants them to produce (no more than two red beads per day), but it certainly is not the workers' fault, and there is nothing that they can do about it until the system changes.

The red bead experiment is of interest because it summarizes the following:

-

Variation is inherent in any process.

-

The system determines workers' performance; until it changes, workers are typically unable to improve their performance.

-

Only management can change the system.

Given an in-control process, some workers will appear to be best or worst on different days, but at least part of this is a matter of luck, not of skill or working harder. When this is the case, rewards or reprimands are likely to do more harm than good.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 181