Chapter 2: Customer Understanding

OVERVIEW

In Volume I of this series, we made a point to discuss the difference between "customer satisfaction" and "loyalty." We said that they are not the same and that most organizations are interested in loyalty. We are going to pursue this discussion in this chapter because, as we have been saying all along, understanding the difference between customer service and customer satisfaction can provide marketers with the competitive advantage necessary to retain existing customers and attract new ones. "Understanding" what satisfaction is and what the customer is looking for can provide the engineer with a competitive advantage to design a product and or service second to none. At first glance, service and satisfaction may appear to mean the same thing, but they do not; service is what the marketer provides and what the customer gets, and satisfaction is the customer's evaluation of the level of service received based on preconceived assumptions and the customer's own definition of "functionalities." The satisfaction level is determined by comparing expected service to delivered service. Four outcomes are possible:

-

Delight ” positive disconfirmation (a pleasant surprise)

-

Dissatisfaction ” negative disconfirmation (an unpleasant surprise)

-

Satisfaction ” positive confirmation (expected level of service)

-

Negative confirmation, which suggests that you are neither managing expectations properly nor delivering good service

In managing service delivery, relying solely on the objective aspects of service is a mistake. Customers base future behavior on their evaluation of the experience they actually had, which is in effect their degree of satisfaction or dissatisfaction. In addition to determining that satisfaction degree, marketers should seek to learn the reasons underlying customers' feelings (the insight) in order to tell the engineers what, how and when to make changes and maintain high satisfaction levels when they are achieved. In researching these areas, marketers should note that the why is not the what; nor is it the how. That is, what happened and how it made customers feel does not tell us why they felt as they did. And not knowing that, managing not only the service that customers experience but also their expectations becomes difficult, if not impossible .

At times, service providers and customers tend to think differently. Consider this dealership example: After conducting 10 focus groups for an automotive company in a medium- size Midwestern city, the researchers discussed the findings in a review meeting with the head of marketing for the company. The researchers noted that, after having spoken with more than 100 recent customers, they had learned that the vast majority were frustrated and unhappy about having to wait more than 15 minutes before getting attended to. The marketing executive interrupted , saying, "Those customers should consider themselves lucky; if they were in the dealerships of one of our competitors , they would have to wait 20 to 30 minutes before they were seen by the service manager."

This example includes all the information needed to explain the difference between customer service and customer satisfaction. The customers in this example defined their personal expectations about the service ” their waiting time experience ” and clearly, a conflict existed between their service expectation (a short wait before being seen by a service manager) and their service experience (waits of more than 15 minutes). Customers then were dissatisfied with the waiting rooms and the dealerships in general. The marketing manager's response to customer dissatisfaction was to note that the waits could have been worse: He knew that competitors' dealerships were worse . He also knew customer waits of more than 30 minutes were not uncommon. In light of these data, he judged the 15- to 20-minute waits in the waiting room acceptable.

Herein lies the conflict between service delivery and customer satisfaction. The important concept for this marketing executive ” and for all marketers ” is that customers define their own satisfaction standards. The customers in this example did not go to the competitors' dealerships; instead, they came to the marketer's dealership with a set of their own expectations in a preconceived environment. When the marketer used his service delivery criteria to defend the waiting time, he simply missed the point.

Unfortunately, this illustration is typical of how many marketers think about customer satisfaction. They tend to relate customer satisfaction directly to their own service standards and goals rather than to their customers' expectations, whether or not those expectations are realistic. To assess satisfaction, marketers must look beyond their own assessments, tapping into the customers' evaluations of their service experience.

Consider, for example, a bank that thought it was doing a good job of measuring service satisfaction but really was too focused on service delivery. This bank had developed a policy that time spent in the lobby room should be less than 15 minutes for all customers. A customer came into the office and waited 12 minutes in the reception area for a mortgage application. Then she waited another five minutes for the loan officer to clear all the papers from his desk from the previous customer and an additional three minutes for him to get the file and all the pertinent information for the current application. As this customer was leaving, she was asked to fill out a customer satisfaction questionnaire. Under the category for reception area waiting time, she checked off that she had waited less than 15 minutes.

Based on this response, the bank's marketing director assumed the customer was satisfied, but she was not; the customer had been told that if she came in for the mortgage loan during her lunch hour , she would be taken care of right away. Instead, she waited a total of 20 minutes for her application process to begin. She did not have time to shop for the gift her son needed that night for a birthday party, and her entire schedule was in disarray. She left dissatisfied.

Understanding the difference between service and satisfaction is the first step in developing a successful customer satisfaction program, and all marketers must share the same understanding. Only customers can define what satisfaction means to them. Here are some practical ways to understand customers' expectations:

-

Ask customers to reflect on their experiences with your services and their needs, wants, and expectations.

-

Talk to customers face to face through focus groups, as well as through questionnaires. A wealth of information can be collected this way.

-

Talk with your staff about what they hear from customers about their expectations and experience with service delivery.

-

Review warranty data.

Remember the three words that can help you learn from your customers: What, how and why. That is, what service did you experience, how did it make you feel, and why did you feel that way? Continual probing with these three perspectives will deliver the answers you need to better manage service to generate customer satisfaction.

As Harry (1997 p. 2.20) has pointed out:

-

We do not know what we do not know

-

We cannot act on what we do not know

-

We do not know until we search

-

We will not search for what we do not question

-

We do not question what we do not measure

-

Hence, we just do not know

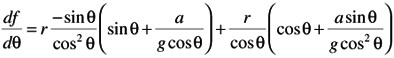

Therefore, part of this understanding is to identify a transfer function. That is, you need a bridge (quantitatively or qualitatively) that will define and explain the dependent variable (the customer's needs, wishes, and excitements) with the independent variable(s) (the actual requirements that are needed from an engineering perspective to satisfy the dependent variable). The transfer function may be a linear one (the simplest form) or a polynomial one (a very complex form).

Typical equations expressing transfer functions may look something like:

Y = a + bx

Y = f(x 1 , x 2 ...x n )

They can be derived from:

-

Known equations that describe the function

-

Finite element analysis and other analytical models

-

Simulation and modeling

-

Drawing of parts and systems

-

Design of experiments

-

Regression and correlation analysis

In DFSS, the transfer function is used to estimate both mean (sensitivity) and variance (variability) of Y s and y s. When we do not know what the Y is, it is acceptable to use surrogate metrics. However, it must be recognized from the beginning that not all variables should be included in a transfer function. Priorities should be set based on appropriate trade-off analysis. This is because DFSS is meant to emphasize only what is critical, and that means we must understand the mathematical concept of measurement.

The focus of understanding customer satisfaction has been captured by Rechtin and Hair (1998), when they wrote that "an insight is worth a thousand market surveys." It is that insight that DFSS is looking for before the requirements are discussed and ultimately set. This will help us in identifying what is really going on with the customer. Let us look at the function first.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 235