Chapter 2: Threats, Promises, and Sequential Games

Overview

“A prince never lacks legitimate reasons to break his promise.”

Machiavelli[1]

One summer while in college I had a job teaching simple computer programming to fourth graders. As an inexperienced teacher I made the mistake of acting like the children’s friend, not their instructor. I told the students to call me Jim rather than Mr. Miller. Alas, my informality caused the students to have absolutely no fear of me. I found it difficult to maintain order and discipline in class until I determined how to threaten my students.

The children’s parents were all going to attend the last day of class. Whereas the students might not have considered me a real teacher, they knew that their parents would. I discovered that although my students had no direct fear of me, they were afraid of what I might tell their parents, and I used this fear to control the children. If I merely told two students to stop hitting each other, they ignored me. If, however, I told the children that I would describe their behavior to their parents, then the hitting would immediately cease.

The children should not have believed my threat, however. After the summer ended, I would never see my students again, so I had absolutely nothing to gain by telling the parents that their children were not perfect angels. It was definitely not in my interest to say anything bad about my students since

-

It would have upset their parents.

-

I realized that their bad behavior was mostly my fault because I had not been acting like a real teacher.

-

The people running this for-profit program would have been furious with me for angering their customers.

Since they were only fourth graders, it was understandable that my students (who were all very smart) didn’t grasp that my threat was noncredible. When making threats in the business world, however, don’t assume that your fellow game players have the trusting nature of fourth graders.

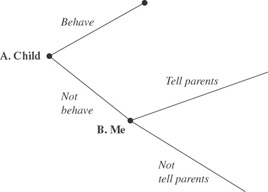

Let’s model the game I played with my students. Figure 1 presents a game tree. The game starts at decision node A. At node A, a child decides whether or not to behave, and if he behaves, the game ends. If he doesn’t behave, then the game moves to decision node B; and at B I have to decide whether to tell the parents that their child has misbehaved. In the actual game the children all believed that at B I would tell their parents. As a consequence the children chose to behave at A. Since it was not in my interest to inform the parents of any misbehavior, however, my only logical response at B would be to not tell their parents. If the children had a better understanding of game theory they would have anticipated my move at B and thus misbehaved at A. My students’ irrational trust caused them to believe my noncredible threat.

Figure 1

[1]The Prince (1514), Chap. 18.

EAN: N/A

Pages: 260