Introducing Wardriving

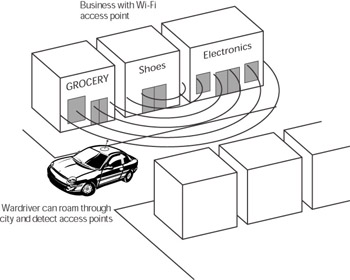

Wardriving is the act of driving around with equipment that can be used to detect Wi-Fi access points located in homes and businesses (see Figure 6-1). It doesn’t require a large investment in equipment or a high degree of technical skill. Anyone can wardrive, and with the proliferation of Wi-Fi networks in homes and businesses, there are plenty of wireless networks waiting to be found.

Figure 6-1: Wardriving

In the days of dial-up computer Bulletin Board Systems (BBS), before the Internet or the World Wide Web, a cracker would use a piece of software called a wardialer to dial a huge range of numbers, one after the other, and listen for a computer to answer at the other end. The wardialer would then log the number, attempt to connect, and, if successful, identify the computer and service at the other end of the line. Wardriving gets its name from comparisons to this cracker activity.

| Cross-Reference | To read more about crackers and other computer criminals see Chapter 3 |

The majority of wardrivers are nothing more than curious Wi-Fi geeks; technophiles who love wireless equipment and enjoy driving around, and discovering and then mapping networks. The members of many Wireless User Groups (WUGs) wardrive to collect data and compile statistics about wireless use and level of security or insecurity of discovered WLANs.

However, harmless geeks aren’t the only people wardriving, and you need to protect your network from the minority of wardrivers that look for unsecured access points for purposes that are more nefarious.

Crackers wardrive to find vulnerable networks that they can break into. Once crackers get inside a WLAN, they can connect to the Internet or attack other computers without law enforcement or security personnel tracking and apprehending them. Efforts to locate the source of the attack lead back to the WLAN from where it originated by the cracker, but not directly to the cracker. This raises a question of liability. Can the courts hold you responsible for crimes that a wardriver commits while using your WLAN without your knowledge? In most cases, the answer is no. In order for you to be criminally liable for the actions of a wardriver, law enforcement must be able to demonstrate that you had intent or that you arranged for a cracker to access your network in order to facilitate the crime.

| Note | Laws relating to wardriving vary among states. See the section “Legality of wardriving” later in this chapter for information regarding different state laws. |

However, depending on the circumstances and the laws of your state you could be civilly liable for the actions of a hacker. For example, if you have a small business and a cracker was able to steal credit card information because you failed to take reasonable steps to secure your network and protect customer data, you may be subject to a lawsuit by customers who’ve had their personal information stolen.

Because of the potential for liability arising from misuse of your WLAN or from theft of personal information, it’s important that you take steps to secure your WLAN. While you may believe you’re unlikely to be the victim of a cracker, given the popularity of wardriving the chances are greater than you may think.

How wardriving works

Wardriving doesn’t require a great amount of technical skill or expensive equipment. Many people have much of what they need lying around their house already. All a would-be wardriver needs before hitting the road is:

-

A laptop with a Wi-Fi adapter or built-in wireless capability

-

Wardriving software (available free on the Internet)

-

A high gain antenna (optional)

-

A power adapter for running the laptop off the car’s battery (optional)

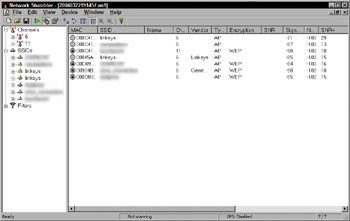

Once the wardriving software is running, all a wardriver has to do is drive around any commercial or residential area and he can detect WLANs. Using a Windows XP laptop and an application named NetStumbler, I was able to detect several WLANs in a rural area of Southern California in just a few minutes (see Figure 6-2). This was without the addition of an external antenna. Had I been in a more populated area I might have discovered hundreds of wireless networks.

Figure 6-2: NetStumbler detecting wireless networks

After identifying a wireless network, a cracker can attempt to connect to it. Unfortunately for WLAN user, connecting to an unsecured WLAN is trivial even for a technical newbie. If you fail to take steps to protect your network, someone may connect to it and use your Internet connection, or access files on your computers, which is why it is so important to know how to protect your network.

Hiding your network

One of the first steps you can take to help protect your wireless network is to turn off the service set identifier (SSID) broadcast on your access point. The SSID is the network name that identifies your WLAN, and access points regularly broadcast data packets, called beacon frames, that announce their presence to the world. Clients and wardrivers can listen for these beacon frames and detect the presence of your access point, as well as discovering your SSID.

Many access points allow you to disable the SSID broadcast. This is a good first step, and it will prevent some wardriving software from detecting your WLAN. However, beacon frames aren’t the only wireless packets that contain the SSID, and tech-savvy wardrivers have software that listens in passive mode and can collect and analyze other network traffic to recover the SSID and detect your access point.

Still, disabling your SSID broadcast can help hide your network from many casual wardrivers, and if they can’t see it, they can’t connect to it.

Changing default settings

Failing to change the default settings on access points is the main reason so many WLANs are at risk. Every piece of networking equipment comes configured with preset or default settings. Manufacturers configure their hardware to facilitate use, not security. They want the device to be simple to set up and use right out of the box, which minimizes customer frustration and cuts down on calls to support centers.

Ease of use doesn’t equal secure, however; it usually results in the opposite. Although devices may have security features built in, manufacturers often assume that users will be able to activate and configure these after they have the device running. Few people ever take the time to enable security features on their access points, let alone reset the default settings that they probably don’t realize are a problem.

A cracker can use the default settings on your access point to identify the make and model of the device, connect to your network, and even take control of it. Default settings for most access points are available online, so you can assume that every cracker knows them. Changing these default settings is an important first step toward protecting your network.

| Cross-Reference | The steps for changing default settings and securing your network are discussed in detail in Chapter 11. After you read the information presented here, I suggest that you proceed directly to Chapter 11 and follow the instructions to secure your network. |

Using the default SSID

Every access point has a default SSID assigned by the manufacturer. Even if you have disabled SSID broadcasting, you should change the default SSID. If you haven’t changed the default SSID, a cracker can use it to identify your access point’s manufacturer and model. For example, the default SSID for most access points manufactured by Linksys Inc. is Linksys.

A cracker who knows which hardware you are using can break into your network with less difficulty. Don’t make it easy for an intruder to gain access. Follow the best practices in Chapter 11, and change your SSID to something unique that doesn’t identify you or your network hardware.

Passwords and usernames

Once a cracker knows which access point you are using, he can use the Internet to look up the default user names and passwords for your particular brand of device. Like the default SSID, the default username and password is public knowledge, and many crackers probably know them by heart.

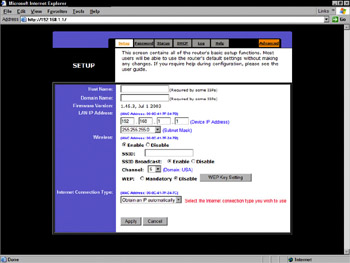

Unless you change the settings, a cracker can connect to your access point, often through a Web browser (see Figure 6-3), and change the device’s configuration. Your username and password are like the keys to your network; you wouldn’t give out the keys to just anybody, would you? Take the time to change the default user- name and password following the steps explained in Chapter 11.

Figure 6-3: Connecting to an access point via a Web browser

Changing the default IP address settings

In Chapter 2, I explained how IP addresses work. Each device has a default IP address, and if the access point is also a router with DHCP functionality it will also have a default IP address range. The default IP address range (or subnet range) is the range of IP addresses available for clients using that particular access point.

It’s important to change your access point’s default IP address to make it more difficult for someone to connect to the device and reconfigure it. If a cracker knows which brand of access point you are using, perhaps because you failed to change the default SSID, he can try to connect to the default IP address for your device. If you are using the default username and password, the cracker can log in and take control of your access point.

Like other default settings, the default IP addresses are well known. Manufacturers, and sometimes users, usually assign a default IP address in the beginning of the network’s IP address range. Many access points have a default IP address of 192.168.0.1 thru 192.168.0.5 or something similar.

The default IP address range on many devices is also well known. A cracker who knows the default IP address range can assign a valid IP address to a wireless adapter and connect to your network in the event that you have disabled DHCP. Knowing the default address range for your access point can make it easier for a cracker to discover the IP address of your access point even if you have changed it.

| Cross-Reference | To read more about IP addresses see Chapter 2. |

You should change the default IP address for your access point to something that isn’t easy to guess. Many people assign an IP address from the first 10 or 20 addresses in the network range. If the network range is 192.168.0.1 thru 192.168.0.255, then the access point is likely to have an address between 192.168.0.1 and 192.168.0.20. Change the default IP address range, and assign an address to your access point that a cracker won’t easily guess.

Avoiding DHCP

Using DHCP simplifies adding clients to your network. Unfortunately, it can also simplify a cracker connecting to your network as well. Even if you have taken the steps above, if you are using DHCP a cracker can connect to your network, and use your Internet connection.

Often, all a hacker has to do to connect to a WLAN that is using DHCP is to associate (connect) with the access point. Windows XP will automatically attempt to connect to a detected wireless network, and DHCP facilitates this by automatically assigning an IP address.

If you have a small network, you can assign static (unchanging) IP addresses to each of your network clients and then disable DHCP. This makes it more difficult for a cracker to obtain a valid IP address, though not impossible. Static IP addresses also make it easier for you to filter network traffic based on IP addresses.

| Cross-Reference | Refer to Chapter 2 for more information about DHCP. See Chapter 11 for more detail about disabling DHCP and assigning static IP addresses. |

Filtering network traffic

Another step you can take to make it more difficult for crackers to connect to your network is to implement filtering on your access point. Not all access points have this feature, but many newer access points with router functionality now include this option.

Filtering enables a router to allow or disallow connections based on the IP address or MAC address of the client attempting to connect. If a computer’s MAC or IP address isn’t on the allow list then the router ignores traffic originating from that computer, filtering it out and preventing that computer from connecting to the network.

Every networking device, including wireless access points and adapters, has a unique MAC address. The manufacturer encodes the MAC address at the factory, and in most cases it’s permanent and users can’t change it. This makes filtering based on MAC address useful and effective.

When you enable filtering on your access point, you are telling the access point which computers it can talk to based on IP address or MAC address, and that it should disregard communication from all other clients.

| Cross-Reference | While filtering is effective, crackers can bypass it. Some wireless adapters allow users to change the adapter’s MAC address. A cracker can listen to network traffic and, using software available on the Internet, analyze data packets to find out the MAC addresses of legitimate clients. He can then assign one of these MAC addresses to his wireless adapter and spoof (impersonate) a legitimate client. This and similar attacks are discussed in Chapter 4. |

Using encryption

Years ago, I took a jungle survival course. When talking about the different dangers we might encounter, the instructor warned us about the numerous large jungle cats in our vicinity (he may have just been trying to scare us, but we took him at his word). When asked what we could do to protect ourselves if we encountered one of the large predators he said, “Run.”

Most of us doubted our ability to outrun a large jungle cat, but when we pointed this out to our instructor he answered, “You’re missing the point; you don’t have to run faster than the cat, just faster than everyone else on your team.” The meaning is that predators aren’t going to work harder than necessary to catch a meal.

Similarly, a cracker isn’t going to work harder than necessary to crack a network. The majority of home users fail to secure their wireless networks, and as a result, their WLANs are easy targets. Given the hundreds of networks that a wardriver finds, it’s likely that your network will be ignored if you have taken steps to secure it. You don’t have to outrun the cracker, just outrun your neighbors.

In addition to the other methods mentioned, you can enable encryption on your network to make it a less appealing target. Most WLAN equipment has Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) functionality built in. WEP encryption isn’t perfect; in fact, most security professionals consider it extremely weak, but it’s better than using no encryption at all.

Most stumbling software, such as NetStumbler, can notify a wardriver if a network has encryption or not. While there is software available that a cracker can use to defeat WEP encryption, it adds one more step and another hurdle to clear. A cracker who isn’t especially proficient will probably just move along rather than bother with the obstacles.

Newer equipment has an improved encryption technology available called Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA). WPA is a more robust encryption algorithm based upon the 802.11i security protocol released by the IEEE. Another version of WPA, known as WPA-2, is in development, and it should be available on some devices by late 2004 or early 2005.

| Cross-Reference | WEP and WPA are discussed in depth in Chapter 10, and their implementation is covered in Chapter 11. |

Legality of wardriving

Let me start this section with a disclaimer; I’m not an attorney, nor am I an expert on criminal law regarding computer systems or communications equipment. Laws governing computer crime vary among states, and the federal government. What’s legal in California may be a felony in Michigan or vice versa. It’s up to you to find out what a cracker can and can’t do where you live.

That said, simply driving around and passively listening for signals from access points shouldn’t be against the law in most places because Wi-Fi uses public, unlicensed frequencies. Listening to Wi-Fi signals is technically legal under federal law.

Connecting to someone else’s private network may be a crime in some states. Laws are evolving to address this, and attorneys are working to apply existing laws, such as those governing telecommunications, to wireless networks. The nature of Wi-Fi and the fact that operating systems like Windows XP are designed to try and automatically connect to access points complicates matters. It’s not unheard of for neighbors to connect to one another’s WLANs unintentionally, often without either party realizing it.

However, if someone deliberately bypasses security features in order to gain access to a private network, the chances are greater that he’s broken computer trespass laws where you live. If he damages or alters those systems, steals information, or uses them to commit another illegal act, then that cracker certainly will be in hot water.

| On The Web | For specific legal information for individual states, visit the National Conference of State Legislatures at www.ncsl.org/programs/lis/cip/hacklaw.htm. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 145