3.1 Is It Better to Overestimate or Underestimate?

3.1 Is It Better to Overestimate or Underestimate?

Intuitively, a perfectly accurate estimate forms the ideal planning foundation for a project. If the estimates are accurate, work among different developers can be coordinated efficiently. Deliveries from one development group to another can be planned to the day, hour, or minute. We know that accurate estimates are rare, so if we're going to err, is it better to err on the side of overestimation or underestimation?

Arguments Against Overestimation

Managers and other project stakeholders sometimes fear that, if a project is overestimated, Parkinson's Law will kick in—the idea that work will expand to fill available time. If you give a developer 5 days to deliver a task that could be completed in 4 days, the developer will find something to do with the extra day. If you give a project team 6 months to complete a project that could be completed in 4 months, the project team will find a way to use up the extra 2 months. As a result, some managers consciously squeeze the estimates to try to avoid Parkinson's Law.

Another concern is Goldratt's "Student Syndrome" (Goldratt 1997). If developers are given too much time, they'll procrastinate until late in the project, at which point they'll rush to complete their work, and they probably won't finish the project on time.

A related motivation for underestimation is the desire to instill a sense of urgency in the development team. The line of reason goes like this:

The developers say that this project will take 6 months. I think there's some padding in their estimates and some fat that can be squeezed out of them. In addition, I'd like to have some schedule urgency on this project to force prioritizations among features. So I'm going to insist on a 3-month schedule. I don't really believe the project can be completed in 3 months, but that's what I'm going to present to the developers. If I'm right, the developers might deliver in 4 or 5 months. Worst case, the developers will deliver in the 6 months they originally estimated.

Are these arguments compelling? To determine that, we need to examine the arguments in favor of erring on the side of overestimation.

Arguments Against Underestimation

Underestimation creates numerous problems—some obvious, some not so obvious.

Reduced effectiveness of project plans Low estimates undermine effective planning by feeding bad assumptions into plans for specific activities. They can cause planning errors in the team size, such as planning to use a team that's smaller than it should be. They can undermine the ability to coordinate among groups—if the groups aren't ready when they said they would be, other groups won't be able to integrate with their work.

If the estimation errors caused the plans to be off by only 5% or 10%, those errors wouldn't cause any significant problems. But numerous studies have found that software estimates are often inaccurate by 100% or more (Lawlis, Flowe, and Thordahl 1995; Jones 1998; Standish Group 2004; ISBSG 2005). When the planning assumptions are wrong by this magnitude, the average project's plans are based on assumptions that are so far off that the plans are virtually useless.

Statistically reduced chance of on-time completion Developers typically estimate 20% to 30% lower than their actual effort (van Genuchten 1991). Merely using their normal estimates makes the project plans optimistic. Reducing their estimates even further simply reduces the chances of on-time completion even more.

Poor technical foundation leads to worse-than-nominal results A low estimate can cause you to spend too little time on upstream activities such as requirements and design. If you don't put enough focus on requirements and design, you'll get to redo your requirements and redo your design later in the project—at greater cost than if you'd done those activities well in the first place (Boehm and Turner 2004, McConnell 2004a). This ultimately makes your project take longer than it would have taken with an accurate estimate.

Destructive late-project dynamics make the project worse than nominal Once a project gets into "late" status, project teams engage in numerous activities that they don't need to engage in during an "on-time" project. Here are some examples:

-

More status meetings with upper management to discuss how to get the project back on track.

-

Frequent reestimation, late in the project, to determine just when the project will be completed.

-

Apologizing to key customers for missing delivery dates (including attending meetings with those customers).

-

Preparing interim releases to support customer demos, trade shows, and so on. If the software were ready on time, the software itself could be used, and no interim release would be necessary.

-

More discussions about which requirements absolutely must be added because the project has been underway so long.

-

Fixing problems arising from quick and dirty workarounds that were implemented earlier in response to the schedule pressure.

The important characteristic of each of these activities is that they don't need to occur at all when a project is meeting its goals. These extra activities drain time away from productive work on the project and make it take longer than it would if it were estimated and planned accurately.

Weighing the Arguments

Goldratt's Student Syndrome can be a factor on software projects, but I've found that the most effective way to address Student Syndrome is through active task tracking and buffer management (that is, project control), similar to what Goldratt suggests, not through biasing the estimates.

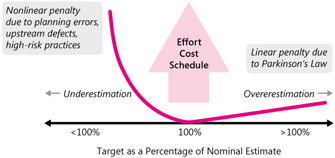

As Figure 3-1 shows, the best project results come from the most accurate estimates (Symons 1991). If the estimate is too low, planning inefficiencies will drive up the actual cost and schedule of the project. If the estimate is too high, Parkinson's Law kicks in.

Figure 3-1: The penalties for underestimation are more severe than the penalties for overestimation, so, if you can't estimate with complete accuracy, try to err on the side of overestimation rather than underestimation.

I believe that Parkinson's Law does apply to software projects. Work does expand to fill available time. But deliberately underestimating a project because of Parkinson's Law makes sense only if the penalty for overestimation is worse than the penalty for underestimation. In software, the penalty for overestimation is linear and bounded—work will expand to fill available time, but it will not expand any further. But the penalty for underestimation is nonlinear and unbounded—planning errors, shortchanging upstream activities, and the creation of more defects cause more damage than overestimation does, and with little ability to predict the extent of the damage ahead of time.

| Tip #8 | Don't intentionally underestimate. The penalty for underestimation is more severe than the penalty for overestimation. Address concerns about overestimation through planning and control, not by biasing your estimates. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 212