Section 15.1. Basic Data Grouping

15.1. Basic Data GroupingWhen you want to simplify your worksheets, you first have to learn how to group data. Grouping data lets you tie related columns or rows into a single unit. Once you've put columns or rows into a group, you can collapse the group, temporarily hiding it and leaving more space for the rest of your data. At its simplest, grouping is just a quick way to help you easily view what you want to see, when you want to see it. It's most handy when you want to show all the key summary information but none of the numbers that you need to crunch to arrive at these results. Note: Excel's grouping settings also affect how your worksheet prints outcollapsed rows or columns don't appear in your printout.

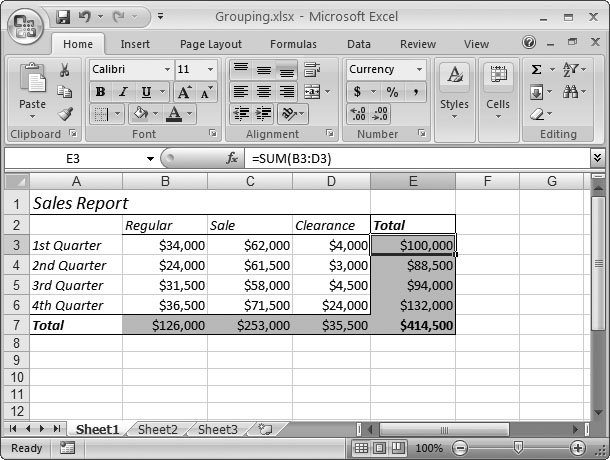

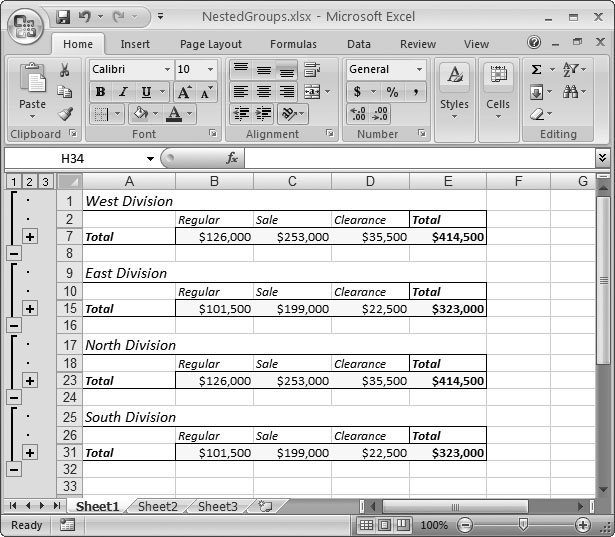

15.1.1. Creating a GroupTo see how grouping can simplify complex worksheets, check out the sales report data shown in Figure 15-1. In this example, the information fits easily into the viewable area of the Excel window, but in a real-world company, you could easily end up needing to extend the worksheet with more columns and rows.

You could add a variety of columns (representing different types of promotions, different discounts from regular prices, or different departments in the store). Or, you may add more rows to cover sales quarters from more than one year, or to track monthly, weekly, or even daily sales totals. In either case, the data would become fairly unwieldy, forcing you to scroll up and down the worksheet, and from side to side. By grouping columns (or rows) together, you can pop them in and out of view with a single mouse click. Note: You may remember from Chapter 5 that you can also use hiding to temporarily remove rows and columns from sight. But grouping is a much nicer approachyou can more easily pop data out of and back into view without going hunting through the menu. It also makes it more obvious to the person reading the worksheet that there's more data tucked out of sight. People more often use hiding to remove gunk that no one ever needs to see. Technically, grouping uses Excel's hiding ability behind the scenes to make grouped cells disappear temporarily. Here are the steps you'd need to follow in order to group several columns together using the sales report example:

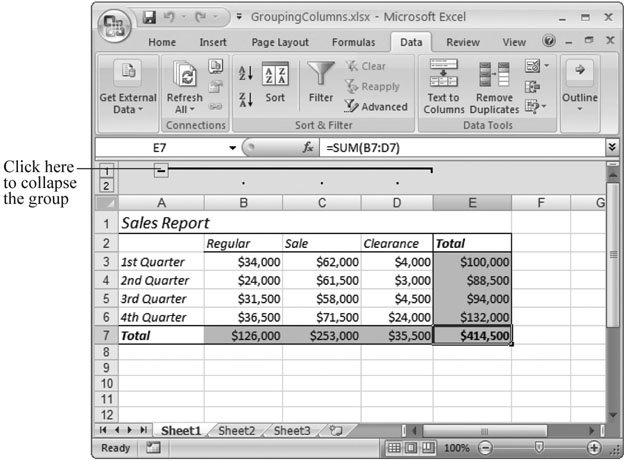

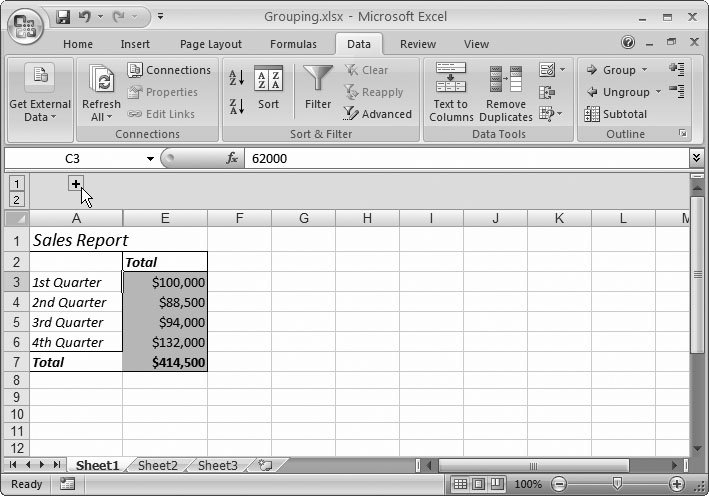

When you group your columns, the worksheet doesn't change, although a new margin area appears at the top of the worksheet, as shown in Figure 15-2. This margin allows you to collapse and expand your groups (see Figure 15-3). To collapse a group, click the minus sign (), which then changes into a plus sign (+). To expand a collapsed group, click the plus sign (+). To remove a group after you've established it, expand the group, select all the columns, and then choose Data

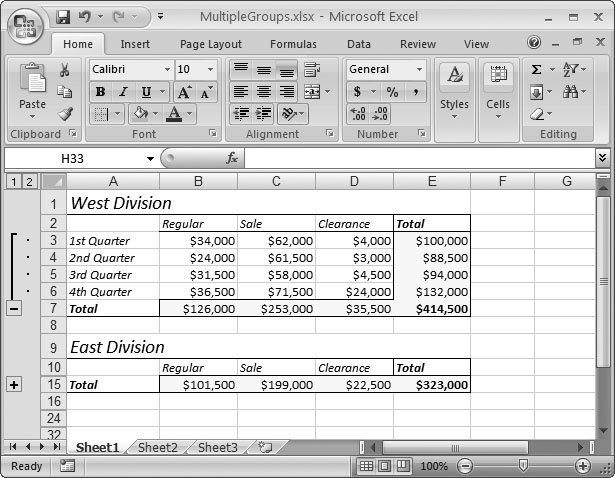

Tip: You can also ungroup a set of columns while the group's collapsed. Just select a range of columns that includes the hidden columns, and then use the Data  Outline Outline  Ungroup command. Even though youve removed the group, the columns remain hidden and trapped out of sight! You can expose these columns after you've removed the group only if you select a range of columns that includes the hidden columns, and then choose Home Ungroup command. Even though youve removed the group, the columns remain hidden and trapped out of sight! You can expose these columns after you've removed the group only if you select a range of columns that includes the hidden columns, and then choose Home  Cells Cells  Format Format  Hide & Unhide Hide & Unhide  Unhide Columns. Unhide Columns. Outline  Group. This time, a margin appears just to the left of the worksheet, allowing you to quickly hide the grouped rows. You can also have groups of rows and groups of columns, as shown in Figure 15-4. Group. This time, a margin appears just to the left of the worksheet, allowing you to quickly hide the grouped rows. You can also have groups of rows and groups of columns, as shown in Figure 15-4.

Note: If you insert a new row between two grouped rows using the Home  Cells Cells  Insert Insert  Insert Sheet Rows command, Excel automatically places the new row into the group. The sames true if you insert a new column between two grouped columns using Home Insert Sheet Rows command, Excel automatically places the new row into the group. The sames true if you insert a new column between two grouped columns using Home  Cells Cells  Insert Insert  Insert Sheet Columns. Insert Sheet Columns. Tip: If you decide to use multiple groups, it makes sense to group related rows or columns. For example, you may group all the columns that have address information into one group. 15.1.2. Nesting Groups Within GroupsAs you've seen, grouping lets you temporarily shrink the size of a large table by removing specific rows or columns. Grouping becomes even more useful when you create a worksheet that has multiple tables of information, like the one shown in Figure 15-5.

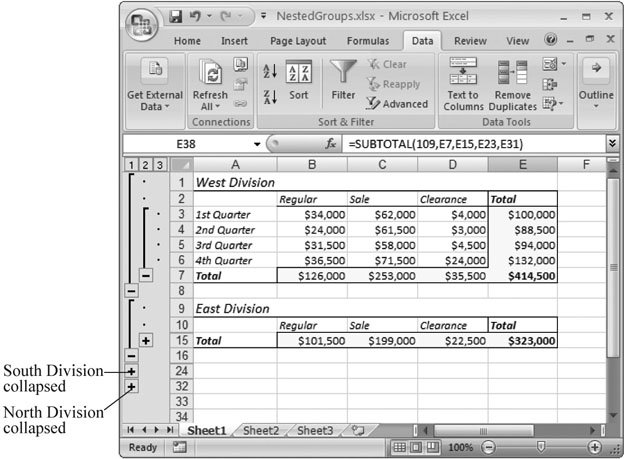

Note: Don't get confused by thinking about Excel's structured tables, which you saw in Chapter 14. With grouping, you can use any combination of cells. Here, the data falls into a tabular structure with easily identifiable rows and columns, but it isn't an official Excel table. Not only can you create separate groups for different tables, you can also put one group inside another. This approach gives you multiple viewing levels. Consider Figures 15-6 and 15-7, which show two views of the same worksheet. This worksheet includes four tables, each of which has two levels of grouping. By collapsing the first-level group for a table, you can hide everything except the summary information (listed in the Total line). By collapsing the second-level group, you can hide the entire table.

Note: The only drawback is that the more levels of grouping you add, the more room Excel needs in the margins at the side of the worksheet in order to display all the grouping lines. Technically, when you add more than one level of grouping, you're adding collapsible outline views to your worksheet, which let you quickly move back and forth between a bird's-eye view of your data and an up-close glimpse of multiple rows.

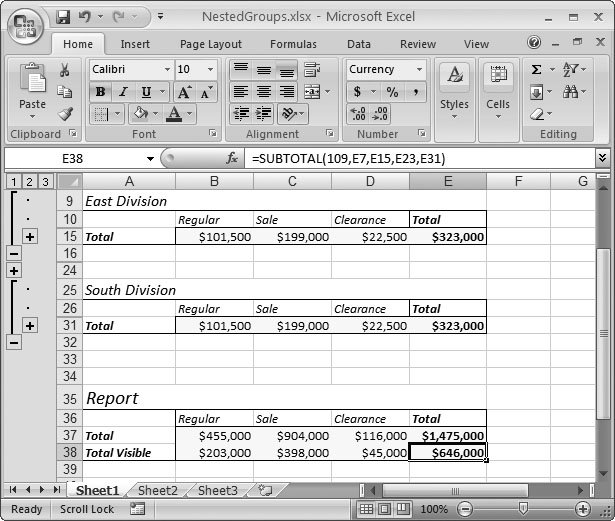

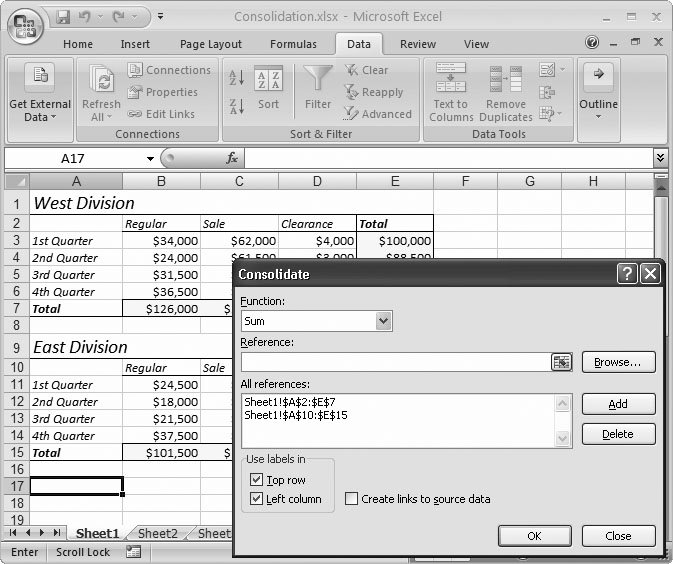

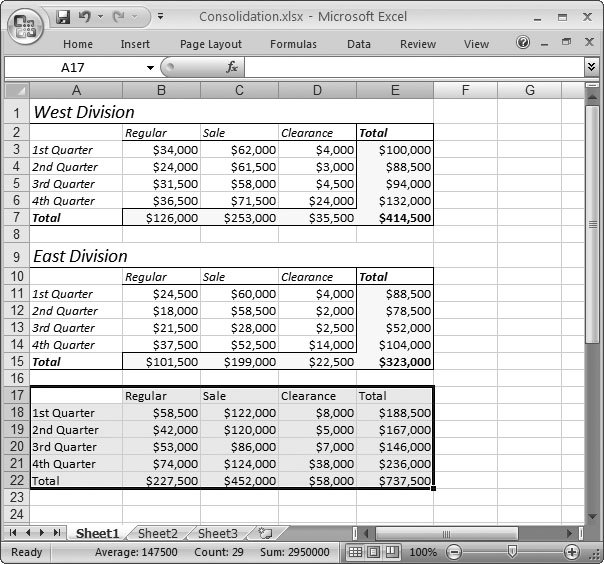

15.1.3. Summarizing Your DataUnderstanding how to quickly collapse and expand tables is all well and good, but before long, you'll want to add up the totals you've collected in these accordionstyle tables. In the subtotaled sales report shown in Figure 15-7, the perfect way to complete this worksheet is to add a final table that sums up all the Total rows listed in the last row of each division. To create a grand summary, you need to employ just a few more formulas. These formulas add the separate subtotals (contained in columns B, C, D, and E) to arrive at a final series of grand totals. The following formula would calculate the total sales in all divisions and all quarters for regular merchandise: =B7+B15+B23+B31 Note: You could, of course, also calculate any of these subtotals by using the SUM( ) function, which is covered in Section 9.2. You'll notice that no matter how you expand or collapse the groups in your worksheet, the result of these formulas is always the same. That's because, whether you're using straight addition (of multiple cells) or the SUM( ) function, Excel takes into account visible and hidden cells. If you're using grouping, however, it may occur to you that it would be handy if you could perform a calculation that deals only with the visible cells. That way, you could choose the portions of a worksheet you want to consider, and the formula could recalculate itself automatically to give you the corresponding summary information. Good news: Excel gives you the power to build this sort of formula. All you need is the awesome SUBTOTAL( ) function. As you may recall from Chapter 14, the SUBTOTAL ( ) function is a useful tool for calculating totals in filtered lists. But it's just as helpful when you apply it to outlines because it ignores collapsed rows and columns. As explained in Section 14.4.5, the first argument (known as the calculation code) you use with the SUBTOTAL( ) function tells Excel the type of math you want to do (summing, averaging, counting, and so on). If you want to ignore the hidden cells in collapsed groups, you have to use the calculation codes above 100. If you want to perform a sum operation, then you need to use the code 109. (For a full list of the SUBTOTAL( ) calculation codes, see Section 14.4.6.) Once you've chosen the calculation code, you need to specify the cells or range of cells you want to add. Here's an example that rewrites the earlier formula to sum only visible cells: =SUBTOTAL(109,B7,B15,B23,B31) Figure 15-9 shows the difference between using the SUBTOTAL( ) function and the SUM( ) function. 15.1.4. Combining Data from Multiple TablesInstead of writing your summary formulas by hand, you can generate a summary table automatically that takes advantage of Excel's ability to consolidate data. Consolidation works if you have more than one table with precisely the same layout. You can use consolidation to take the different tables shown in the sales report (West Division, East Division, and so on) and calculate summary information. Excel creates a new table that has the same structure but combines the data from the other tables. You can choose how Excel combines the data, including whether the numbers should be totaled, averaged, multiplied, and so on. Note: Data consolidation works with any sort of tabular data. You don't need to create the structured tables you learned about in Chapter 14.

Data consolidation works with any worksheet (with or without grouping); you can even use it to analyze data in identically structured tables from different worksheets. Note: For best results, you should consolidate data with the exact same layout only. Although you can coax Excel into combining differently sized ranges of data, it's all too easy to confuse yourself about what is and isn't combined. To make life easier, only consolidate ranges that have numeric data or identical labels (like column or row titles). Leave out the overall table title because there's no way to consolidate it. To consolidate the sales report data, follow these steps:

Data consolidation's big disadvantage is that it generates a table filled with numbers, rather than formulas. Microsoft's engineers probably designed the consolidation feature this way so you can consolidate data from multiple files and not worry about losing the information if the source files move or their structure changes. But this behavior means that if you modify any of the sales figures, the summary table doesn't update. Instead, you'll need to generate a completely new summary table by using the Data |