Putting It All Together

| By this point, you've spent some time with all of Aperture's features. Hopefully, you've seen that not only does the program provide most of the image editing features you need, and very smooth integration with applications that have any other features you want, but that these features are so seamlessly integrated that you can quickly move from task to task without the hassle of saving files, invoking specific modes, or saving special versions. So now we'll sum up by taking a look at a real-world example of how you might use Aperture. There are many ways to exploit Aperture's power and this is just one possible workflow, but hopefully this description will help you understand how to use all the tools you've learned about in an Aperture-driven approach to your photo post-production work. Assuming that you've returned from a digital shoot with a camera full of images, here's how you might construct your editing pipeline: Copy your Images to your Hard DriveAperture can import images directly from your camera's media card, but I prefer to first copy the images to my Mac's drive. As you'll see later, this approach facilitates a specific long-term archiving strategy. Also, copying images to your hard drive using the Finder is speedier than copying directly from the media card. If you're shooting in the field and need to free up your media card as quickly as possible, this speed difference may be important. Note If you're a film shooter, then you'll replace this first step with your scanning practice of choice. At the end of your scanning operation, you'll have a folder full of images that you'll take on to the next step. Import Images into ApertureAfter you've imported your images to a folder on your drive, import them into Aperture. Because Aperture's Import dialog box shows you image thumbnails, use the Import step as the first major edit of your selection. While some people insist on importing every image, because you never know what you might need, there are usually some images that are plainly bad. Don't bother importing the wildly out-of-focus images, the images that are plainly too over- or underexposed to be usable, lens cap shots, and so forth. If your shoot went well, you'll already have enough media to wade through, so why complicate your work? If you're not sure about the exposure or focus of an image, import the image anyway; you can always delete it later. Stack your images in the Import dialog box, as this will give you a leg up on your organization efforts. Tip If you're going to use this technique, when you initially copy your images from your media card, it's best to copy to a drive that's different from the drive where your Aperture library is stored. Your Mac is usually faster when it copies from one drive to another. If you copy your images to a secondary drive, then your Aperture import operations will be slightly faster. Sort, Organize, Rate, and Keyword your ImagesUsing the tools you learned about in Chapter 4, get your images organized. Aperture is very flexible in this regard, and you have lots of tools and options at your disposal. Organize your images into stacks to keep related shots together, and start selecting your pick images. If you find images that plainly aren't usable, delete themagain, there's no reason to clutter your library. You don't have to apply keywords, but they can make your future organization and image access much easier. You don't have to apply ratings, either, but you do need some way to keep track of your pick images. If you're diligently stacking your pictures, then use the stack pick feature. One of the best ways to keep track of your picks is to create an album for them within your project. You can either use a regular album and drag your picks into it, or use a Smart Album and configure it to include five-star images or images with a particular keyword whatever marker you like for tagging your best images. Edit your PicksOnce you've found your picks, you're ready to start editing. If you're shooting raw, you'll have some additional editing controls, but of course with Aperture, there's no separate raw conversion step that you have to work into your pipeline. Your raw controls sit right alongside your other editing tools. If you've placed your picks in an album, you can simply work your way through that album and edit each imageyou won't even have to look at your reject images. Sometimes, once you start editing, you may realize that the edit you want to make is not possible on your pickperhaps the image doesn't have enough usable data, or there's an exposure problem you didn't notice earlier. If your images are stacked, you can immediately open the stack and look for a better candidate, all without ever leaving your album of pick images. If you want to experiment with different edits, create new versions. And remember: if you need to perform any edits in Photoshop, try to do those as early as possible in your editing process. Create your OutputAfter editing your picks, create whatever output you need. Depending on your workflow needs and the needs of your client, you may actually start outputting before you're done editing. For example, if you need to show proofs to a client, you may put up a Web site or make some sample prints. Often, as you prepare outputs, you'll recognize additional edits that need to be made. As you saw in the last chapter, these edits can be made without returning to any kind of special editing mode. Outputting your images will often lead you to create additional versions, as you may need special corrections for prints or other output. As you saw in the previous chapter, you may want to create Smart Albums to keep track of versions of images that you have tailored to particular types of output. You may go through several output steps as your clients refine their ideas, change their minds, decide they need additional types of output, and so on. You should find that Aperture's flexibility makes short work of these issues.

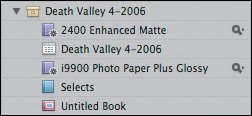

Back up your ImagesHow often you should back up depends entirely on how much work you're willing to lose. Personally, I don't want to lose even a day's worth of work, so at the end of each workday I fire up the drive that contains my vault and then click the Update button to update my backup. If you've just finished a particularly difficult group of edits that you absolutely could not re-create, consider performing a backup then. Since Aperture's progressive backup scheme is fairly speedy, this is not a terrible inconvenience. Archive your ImagesBecause Aperture currently limits your library to a single volume, it's not always practical to keep all of your images in your Aperture library. Fortunately, for most day-to-day work, you probably don't need access to all of your images. If you've been following this procedure, then your Aperture library currently contains only your select images, adjusted and ready to use. The initial image copy that you placed on your computer may contain many additional images, including copies of some images that you may have deleted after importing into Aperture. If you copy this original batch of images to CD or DVD for long-term storage, then you'll have archived copies of all of your original master files. You can then delete the files that you copied to your drive in the first step of this process. Catalog your ArchiveWith your original images burned to disk, you'll want some way of keeping track of them. Using an image cataloging program like iView MediaPro or Extensis Portfolio, you can build a thumbnail catalog of all of your archived media. You now have easy access to all of your images. Your Aperture library contains all of your edited select images, ready for printing (and if you've properly stacked your pictures, you have easy access to related alternates). Your Aperture library also contains all of your outputWeb sites, books, prints, and so on. Thanks to Aperture's nondestructive editing and flexible interface, you can quickly get to your images, edit them, create new versions, and output them in multiple ways. You can throw together portfolios, post sample images, and more, without having to wade through lots of unused, irrelevant alternates. If you need to open an image in Photoshop, you can launch it in Photoshop from within Aperture. For safekeeping, your Aperture library itself is archived on another drive. Finally, if you need access to an image that's not in your Aperture library, you can search for it in the catalogs that you've built with your image cataloging program, and then import the image from one of your archived CDs or DVDs. Hopefully, with an Aperture-driven production, you'll find that your editing tasks are easier, and that you're spending the bulk of your time working with your images, rather than simply managing them. With all that extra time, you can go out and shoot more! |