Chapter One. What Is Aperture?

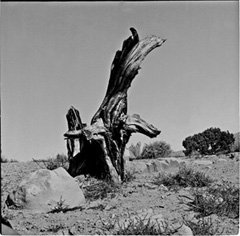

| In the spring of 1995, I found myself driving across central Utah. Though I owned a digital camera, it was a Kodak DC40 with a resolution of 756 x 504 pixels. Digital photography was in its infancy, with the world's first mass-market 1-megapixel camera still a year away, so I was packing film cameras. In addition to a regular 35mm SLR, I had a medium-format twin-lens reflex camera. I shot a lot of pictures on that trip, both 35mm and medium format. When I got home, I carried my dozen or so rolls of film to the photo lab, and then a few days later I picked up my negatives and contact sheets. It was only when I returned home with the results that I realized that some images that I remembered shooting were not there. I dug around in a backpack and found one more roll of 120 film. I wasn't in a mood to return to the photo lab, so I stuck the roll of film in the refrigerator for safekeeping until I needed to drop off more film. Six years later I moved out of that apartment. The undeveloped roll was still in my fridge, so I diligently packed it up and moved it across town to the new apartment, where I carefully installed it in my new refrigerator. That was three years ago. About a week ago, with no memory of what might be on the undeveloped roll, I finally took the film to the lab and had it developed. For the most part, there wasn't much there worth printing, but I did find one fairly nice picture of a tree (Figure 1.1). Total time from shooting to printing: nine years. In modern digital photography terms, this is what is known as a very bad workflow. Figure 1.1. This recently developed image sat on a roll of film in my refrigerator for nine years before I finally got around to having it processed.

I shot exclusively with film for about another year after that picture was taken, but within three years I was shooting entirely digitally. One of the great appeals of digital photography is the immediate feedback. Rather than waiting days (or, pathetically, years) to see prints of your images, when you shoot digital you can go from shoot to final output incredibly quickly. However, whether you're a hobbyist or professional photographer, you've probably already discovered that, when shooting digital, it's easy to become overwhelmed by a tremendous number of images. What's more, many of these images need to be adjusted and edited, and you may want to create separate versions of some or all of them for Web output and printing. Ultimately, all of your images and their attendant versions need to be archived somewhere. Together, all of these factors can quickly add up to an organizational nightmare. While these problems aren't anything that film photographers haven't faced for years, when shooting digital, things can quickly become more complicated simply because digital cameras allow you to produce a much higher volume of images. And with the simplicity of digital editing, you'll be more inclined to experiment with different approaches to editing and correcting, creating even more images, and possibly a version control headache. Finally, because digital processing can be so speedy, people increasingly expect very fast turnaround, meaning that you often need to get from importing to finished output quickly. Apple Aperture is designed to address your entire digital photography post-production workflow. With it, you can easily import your images from your camera or flash media; sort and arrange your images to select only the pictures that deserve further attention; edit, correct, and output your images electronically and as hard-copy prints; and then archive your imagesall within a single unified environment. Aperture provides some groundbreaking sorting and comparing tools and wraps your entire post-production process into an interface that allows you to freely re-sort your images while editing or apply edits while sorting, or do both while outputting your files. Because Aperture never locks you into a specific mode, you're free to make last-minute adjustments and to change your overall workflow to fit the needs of particular images or clients. Apple designed Aperture to perform 80 to 90 percent of the edits and tasks that most photographers need to apply to most images. While Aperture doesn't provide the editing power of Adobe Photoshop, it wasn't intended to. Rather, Aperture helps you manage your images and edit the bulk of them, leaving Photoshop to handle the pictures that require more complex tools and techniques. To facilitate these processes, the program includes an easy "round-trip" mechanism that lets you integrate Aperture with Photoshop or any other image editor. Aperture provides the following editing features:

Aperture's interface frees you from the hassle of opening, closing, and managing separate documents by letting you work with your images in big stacks, just as if you were manipulating slides on a light table. You can set them side by side, rearrange them, order them, mark them up, and much more. Finally, once you've selected your best images and edited them to your liking, you can have Aperture help you create contact sheets and final prints, e-mail attachments, Web galleries, or even professional-looking coffee table books. Real World Aperture explains all of these features and shows you the best way to use them, no matter what your level of expertise or style of shooting.

Note At the time of this writing, Adobe's new Lightroom application has just entered its public beta process. While Lightroom will plainly be a direct competitor to Aperture, it's too early to fairly compare their feature sets. However, it is safe to say that both programs will end up with similar features, but different interface approaches. If you're worried about which one is the "right" choice, the decision will most likely come down to which program has the interface and output quality that you prefer, since the toolsets will probably be very similar. |

- Article 366 Auxiliary Gutters

- Article 400: Flexible Cords and Cables

- Article 645 Information Technology Equipment

- Article 702 Optional Standby Systems

- Example No. D10 Feeder Ampacity Determination for Adjustable-Speed Drive Control [See 215.2, 430.24, 620.13, 620.14, 620.61, Tables 430.22(E), and 620.14]