Starting Up and Logging In

Of course, when you first turn on your computer, it must go through a startup process. Startup begins with the Apple startup chime, a signal that the most basic hardware elements are operational. After the chime, the remaining hardware tests continue as the computer tests the hard drive for basic errors. After this, the remaining hardware elements activate as the full operating system software loads into RAM from a disk.

Starting up your computer

You start up a Macintosh by pressing any of the following:

-

The Power button on the computer

-

The Power key on the keyboard, if the keyboard has one

-

The Power button on most Apple flat-panel displays (on some older display models, the power button only turns the display on or off)

Once upon a time, the familiar Happy Mac icon was displayed in the center of the screen while the Mac OS loaded. Mac OS 10.2 retired Happy Mac, replacing it with a solid grey Apple logo. A spinning set of bars below the Apple logo indicates that the computer is busy loading the core OS elements. Figure 2-1 illustrates this stage of the startup process.

Figure 2-1: A gray Apple logo with a spinning set of bars is among the first stages of the startup process.

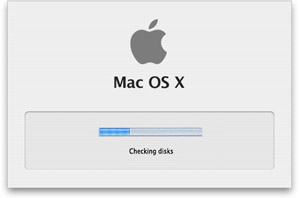

Soon a Mac OS X greeting appears together with a gauge that measures startup progress, and a sequence of brief messages reports steps in the startup process. The spinning disk changes to an arrow-shaped pointer. This pointer tracks mouse movement, but clicking the mouse button has no effect at this time. Figure 2-2 illustrates this part of the startup process.

| Note | You can set some older Macintosh computer models to start up with Mac OS 9 instead of Mac OS X. In this case, a Mac OS 9 greeting appears during startup and the Mac OS X environment is not available after startup. Chapter 13 explains how to select the system you want to use for startup. |

Figure 2-2: A progress gauge and a series of messages report on later stages of the startup process.

Logging in to Mac OS X

After the startup process has begun, OS X loads all basic system elements, and completes activation of kernel (background) operations, a login procedure begins. The login procedure is a means of identifying yourself to your computer. This is both a means of ensuring that your computer activates your particular environment (called your user account), and it’s an effort to keep unauthorized people from using the computer. The login procedure is mandatory but can be automated. In fact, Mac OS X is initially configured for automatic login and remains that way unless someone sets it for manual login. Upon completion of the login process, the appropriate user account is activated and the user can interact with his or her OS X environment.

What login accomplishes

The login procedure accomplishes two things.

-

It proves that you are authorized to use the computer.

-

It establishes which user you are, and this user identity determines what you can see and do on the computer.

Your user identity is especially important if you or an administrator has set up your computer for multiple users, such as members of a family or several workers in an office, because each user has personal preference settings and private storage areas. For example, you may prefer a different background picture on the screen, and you may not want other users to have access to the data you store on the computer or all the application programs you use. As mentioned in the opening Chapter, Mac OS X is a truly multi-user operating system. Since more that one user account can be set up on a particular computer, it’s important to identify each user via a login. You can find information on setting up Mac OS X for multiple users in Chapter 14.

If you have left your computer configured for the default automatic login, you do not get the distinct honor of seeing the login screen. After the startup sequence, the computer just activates your user account, and all elements of your account are available. If you have configured your computer for manual login, Mac OS X displays a login window, and you must provide a user account name and password before the startup process can continue. Instead of logging in, you may shut down or restart your computer by clicking the appropriate button in the window. The login window will show one of two screens. Each is covered under the following headings. Figure 2-3 shows examples of both types of login window.

Figure 2-3: When logging in to Mac OS X, you may get to select a user account from a list (left) or you may have to type a valid account name (right).

Logging in with a list of user accounts

If the login window shows a list of users, log in by following these steps:

-

Use the mouse to click your account name. The initial login window contents change to show your account only, along with a space for entering a password. Figure 2-4 shows an example of this phase of the login process.

Figure 2-4: After clicking one of the account names listed in the initial login window, you must enter the password for the account.Note If your user account name is not listed, you can still log in. To do this, click Other at the bottom of the list of account names and continue at Step 1 in the next procedure. If the account list doesn’t include Other, you can’t log in by entering an account name. Get help from the person who configured the computer for multiple users.

-

Type your password. You can’t read what you type because, for privacy, the password displays it as a sequence of dots. Capitalization counts in the password; upper and lower-case letters are not interchangeable. If you don’t know the password for the selected user account, click the Go Back button to return to the initial login window and select a different user. If you don’t know the password for any account, check with the person who configured your computer for multiple users.

-

Press Return (or Enter) on the keyboard or use the mouse to click Log In. The login window fades, and soon the Mac OS X desktop and menu bar appear, possibly together with windows, icons, and the Dock. You can read more about the menu bar and the other objects in later sections of this Chapter.

Logging in without a list of user accounts

If the login window shows blank spaces for user account name and password, as shown previously in Figure 2-3, follow these steps to log in:

-

Type your user account name, press the Tab key, and then type your password. You can read the name you type, but for privacy, the password displays as a sequence of dots. Capitalization matters only in the password field. If you don’t know both your account name and password, check with the person who configured your computer for multiple users.

-

Press Return (or Enter) on the keyboard or use the mouse to click Log In. The login window goes away, and soon the Mac OS X menu bar appears, possibly together with windows, icons, and the Dock. You can read more about the menu bar and the other objects in later sections of this Chapter.

Dealing with login problems

If the login window shakes back and forth (like someone shaking his head no), either you entered an incorrect password for your specified user account name, or Mac OS X did not recognize the user account name you entered. The Password space clears so that you can retype the password and press Return or click Log In. If you typed a user account name and you need to retype it, press the tab key to highlight the Name space. If you selected a user account from a list, you can select a different account by clicking the Go Back button.

| Note | Even if you’re the only person who uses your computer, some of the data stored on it is protected so that you can’t change it or remove it. This protects the integrity of the operating system (often referred to as protecting users from themselves). |

As you do more and more important work on your computers, such as banking, reviewing credit reports, submitting proposals to clients, trading stocks, or writing Mac OS X guidebooks, your computer fills up with critically important and very sensitive information. In addition, most types of high-speed Internet connections keep your Mac available via the Internet 24 hours a day.

Through your DSL or Cable Modem or (cough cough) dial-up service, your Mac is open and available to countless computers around the world. Because of its basis in Unix (a fact that Apple marketing brings up at every turn), the security options you have with OS X are varied and powerful. That being said, Mac OS X is more open to misuse because of its Unix base. Unix has had over 30 years of evolution to enable the discovery of both loopholes and solutions to security.

Other users can turn the security options on or off; configure your computer for total remote control via the Internet, and guess your password more easily than you might imagine. As a result, your hot new Mac can become the new best friend of a hacker, who can steal or erase your documents as well as launch attacks that crash your machine or network,. Unix is a very powerful tool. Like a hammer or circular saw, Unix can build, but it can also destroy. The first line of defense against any type of unauthorized access is a tough password that you keep secret. For advice on picking a good password, see Appendix A.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 290