9.3 Documentation

9.3 Documentation

Documentation is essential at all stages of handling and processing digital evidence. Documenting who collected and handled evidence at a given time is required to maintain the chain of custody. It is not unusual for every individual who handled an important piece of evidence to be examined on the witness stand.

Continuity of possession, or the chain of custody, must be established whenever evidence is presented in court as an exhibit ... Frequently, all of the individuals involved in the collection and transportation of evidence may be requested to testify in court. Thus, to avoid confusion and to retain complete control of the evidence at all times, the chain of custody should be kept to a minimum. (Saferstein 1998)

So, careful note should be made of when the evidence was collected, from where, and by whom. For example, if digital evidence is copied onto a floppy diskette, the label should include the current date and time, the initials of the person who made the copy, how the copy was made, and the information believed to be contained on the diskette. Additionally, MD5 values of the original files should be noted before copying. If evidence is poorly documented, an attorney can more easily shed doubt on the abilities of those involved and convince the court not to accept the evidence.

Documentation showing evidence in its original state is regularly used to demonstrate that it is authentic and unaltered. For instance, a video of a live chat can be used to verify that a digital log of the conversation has not been modified - the text in the digital log should match the text on the screen. Also, the individuals who collected evidence are often called upon to testify that a specific exhibit is the same piece of evidence that they originally collected. Since two copies of a digital file are identical, documentation may be the only thing that a digital investigator can use to tell them apart. If a digital investigator cannot clearly demonstrate that one item is the original and the other is a copy, this inability can reflect badly on the digital investigator. Similarly, in situations where there are several identical computers with identical components, documenting serial numbers and other details is necessary to specifically identify each item.

A videotape or similar visual representation of dynamic onscreen activities is often easier for non-technical decision makers (e.g. attorney, jury, judge, manager, military commander) to understand than a text log file, Although it may not be feasible to videotape all sessions, important sessions may warrant the effort and expense. Also, software such as Camtasia, Lotus ScreenCam, and QuickTime can capture events as they are displayed on the computer screen, effectively creating a digital video of events. One disadvantage of this form of documentation is that it captures more details that can be criticized. Therefore, digital investigators must be particularly careful to follow procedures strictly when using this approach.

Documenting the original location of evidence can also be useful when trying to reconstruct a crime. When multiple rooms and computers are involved, assigning letters to each location and numbers to each source of digital evidence will help keep track of items. Furthermore, digital investigators may be required to testify years later or, in the case of death or illness, a digital investigator may be incapable of testifying. So, documentation should provide everything that someone else will need in several years time to understand the evidence. Finally, when examining evidence, detailed notes are required to enable another competent investigator to evaluate or replicate what was done and interpret the data.

It is prudent to document the same evidence in several ways. If one form of documentation is lost or unclear, other backup documentation can be invaluable. So, the computer and surrounding area, including the contents of nearby drawers and shelves, should be photographed and/or videotaped to document evidence in situ. Detailed sketches and copious notes should be made that will facilitate an exact description of the crime scene and evidence as it was found.

9.3.1 Message Digests and Digital Signatures

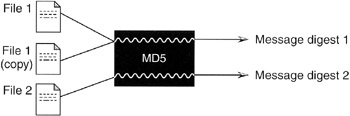

For the purposes of this text, a message digest algorithm can be thought of as a black box that accepts a digital object (e.g. a file, program, or disk) and produces a number (Figure 9.2). A message digest algorithm always produces the same number for a given input. Also, a good message digest algorithm will produce a different number for different inputs. Therefore, an exact copy will have the same message digest as the original but if a file is changed even slightly it will have a different message digest from the original.

Figure 9.2: Black box concept of the message digest.

Currently, the most commonly used algorithm for calculating message digests is MD5. There are other message digest algorithms such as SHA, HAVAL, and SNEFRU. SHA is very similar to MD5 and is currently the US government's message digest algorithm of choice.

The [MD5] algorithm takes as input a message of arbitrary length and produces as output a 128-bit "fingerprint" or "message digest" of the input. It is conjectured that it is computationally unfeasible to produce two messages having the same message digest, or to produce any message having a given prespecified target message digest. (RFC1321 1992)

Note the use of the word "fingerprint" in the above paragraph. The purpose of this analogy is to emphasize the near uniqueness of a message digest calculated using the MD5 algorithm. Basically, the MD5 algorithm uses the data in a digital object to calculate a combination of 32 numbers and letters. This is actually a 16 character hexadecimal value, with each byte represented by a pair of letters and numbers. Like human fingerprints and DNA, it is highly unlikely that two items will have the same message digest unless they are duplicates.

It is conjectured that the difficulty of coming up with two messages having the same message digest is on the order of 264 operations, and that the difficulty of coming up with any message having a given message digest is on the order of 2128 operations. (RFC1321 1992)

This near uniqueness makes message digest algorithms like MD5 an important tool for documenting digital evidence. For instance, by computing the MD5 value of a disk prior to collection, and then again after collection, it can be demonstrated that the collection process did not change the data. Similarly, the MD5 value of a file can be used to show that it has not changed since it was collected. Table 9.1 shows that changing one letter in a sentence changes the message digest of that sentence.

| DIGITAL INPUT | MD5 OUTPUT |

|---|---|

| The suspect's name is John | c52f34e4a6ef3dce4a7a4c573122a039 |

| The suspect's name is Joan | c1d99b2b4f67d5836120ba8a16bbd3c9 |

In addition to making minor changes clearly visible, message digests can be used to search a disk for a specific file - a matching MD5 value indicates that the files are identical even if the names are different. Notably, an MD5 value alone does not indicate that the associated evidence is reliable, since someone could have modified the evidence before the MD5 value was calculated. Ultimately, the trustworthiness of digital evidence comes down to the trustworthiness of the individual who collected it.

Digital signatures provide another means of documenting digital evidence by combining a message digest of a digital object with additional information such as the current time. This bundle of information is then encrypted using a signing key that is associated with an individual or a small group. The resulting encrypted block is the signature - showing that the digital data is intact (e.g. an MD5 value), when the object was signed, and who performed the operation, that is, the owner(s) of the signing key.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 279

- Using SQL Data Manipulation Language (DML) to Insert and Manipulate Data Within SQL Tables

- Using Keys and Constraints to Maintain Database Integrity

- Performing Multiple-table Queries and Creating SQL Data Views

- Retrieving and Manipulating Data Through Cursors

- Working with Ms-sql Server Information Schema View