Planning the Organization

The best place to start planning an Exchange organization is at the top, that is, you determine how your system will look. Planning at this level primarily involves determining the number of routing groups and administrative groups that you need in the organization and deciding where the boundaries of those groups should be. You also need to plan any messaging links between those groups. Before you get started on these plans, however, you need to establish a convention for naming the various elements of the organization.

Establishing a Naming Convention

The requirement that names be unique is common to any system with a directory of users, resources, and servers. Because Exchange Server provides various migration tools, duplication can occur when different systems are migrated to an Exchange system. You should review the systems for possible duplication and take appropriate precautions—such as changing a name or deleting old accounts—before migrating multiple systems to Exchange Server.

Large Exchange systems can grow to include thousands of users worldwide and many routing groups and servers. Most names cannot be changed once an object has been created. Certain objects, such as user mailboxes, have different types of names as well. Before you install your first Exchange server, you need to establish a convention for naming the primary types of objects in your Exchange organization: the organization, groups, servers, and recipients.

Establishing a naming convention for distribution groups, as well as for users and contacts that appear in Active Directory, is a great help to Exchange users. Furthermore, distributing administration among multiple administrators in different regions can help to apply a naming standard to connectors and other Exchange objects.

| Caution | Network and messaging systems should avoid using invalid characters in their names. Some systems do not understand invalid characters, and other systems misinterpret them as special codes (sometimes called escape sequences). This misinterpretation can cause these systems to try to interpret the remainder of a name as a command of some sort. The result, of course, is failure to communicate electronically and, perhaps, errors on the network or messaging systems. Although the list of invalid characters can vary, most systems consider some or all of the following, along with the space character (entered by pressing the spacebar on the keyboard), invalid characters: \ / [ ] : | < > + = ~ ! @ ; , “ ( ) {}’ # $ % ^ & * - _ Avoid using invalid characters in any names, even if you find that Windows or Exchange Server will allow you to do so. |

Organization Names

The organization is the largest element of an Exchange system, and its name should typically reflect the largest organizational element of your company. Usually, an organization is named after the enterprise itself, although it is possible to create multiple organizations in an enterprise and for the organizations to communicate with one another. Organization names can contain up to 64 characters, but to facilitate administration, limiting their length is good practice. Keep in mind that users of external messaging systems might need to enter the organization name manually, as part of the Exchange users’ e-mail addresses.

| Caution | When you install the first production Exchange server, be sure that the organization name you specify is correct. If this means waiting for management’s approval, so be it. Changing the organization name later is possible but requires a good bit of reconfiguration. Also, be aware that the Simple Mail Transport Protocol (SMTP) address space uses the organization and routing group names to construct e-mail addresses for the Internet. The SMTP address space can be changed, but doing so can be a hassle and a cause of confusion for other Exchange administrators later. |

Routing Group Names

The convention for naming routing groups varies, depending on how the boundaries of the groups are established. In a typical Exchange system design, routing groups are named by geographic region or by department because routing group boundaries are determined based on wide area network (WAN) links and workgroup data flow. Like the organization name, routing group names can contain up to 64 characters, but keeping them as short as possible is best. Again, users of some external messaging systems might need to enter the name of the routing group as well as the organization name when sending e-mail to users of your Exchange system.

Server Names

The server name for an Exchange server is the same as the NetBIOS name of the Windows server on which Exchange Server 2003 is installed. Therefore, you should establish naming conventions for servers before installing Windows. You can determine the name of a Windows server on the Network Identification tab of the System utility in Control Panel. NetBIOS server names cannot be more than 15 characters long.

When installing an Exchange Server in an enterprise network, one recommendation for naming the server is to use its location or the type of function that the server will provide. You can end the name with one or two digits to allow multiple Windows servers in the same location providing the same network function. For example, an Exchange server in a company’s London office could be named LON-EX01.

Recipient Names

Recipient names work a bit differently from the names of the other objects. Exchange Server allows several types of recipients, including users, contacts, groups, and public folders. (Public folders are discussed later in this chapter.) Each of the other types of recipients actually has four key names, which are shown on the General tab of the object’s property sheet (Figure 6-1):

Figure 6-1: Elements of a recipient’s name.

-

First Name The full first name of the user.

-

Initials The middle initial or initials of the user.

-

Last Name The full last name of the user.

-

Display Name A name that is automatically constructed from the user’s first name, middle initial or initials, and last name. The display name appears in address books and in the Exchange System snap-in, so it is the primary way Exchange users search for other users. Display names can be up to 256 characters long.

A naming convention should take into account the outside systems to which Exchange Server might be connecting. Many legacy messaging and scheduling systems restrict the length of recipient names within their address lists. Although Exchange Server allows longer mailbox names, the legacy system might truncate or reject them, resulting in duplicates or missing recipients. In addition, messages could show up in the wrong mailboxes or might not be transmitted at all. A common length restriction in legacy systems is eight characters. You can avoid many problems if you keep mailbox names to eight characters or fewer.

The names that you establish for objects in your Exchange organization determine the addresses that users of external messaging systems use to send messages to your recipients. Foreign systems do not always use the same addressing conventions as Exchange Server. Therefore, Exchange Server must have a way of determining where to send an inbound message from a foreign system. For each type of messaging system to which it is connected, Exchange Server maintains an address space consisting of information on how foreign addressing information should be used to deliver messages within the Exchange organization.

Suppose you set up Exchange Server so that your users can exchange e-mail with users on the Internet. In this situation, Exchange Server would support the SMTP address space by maintaining an SMTP address for each recipient object. A user on the Internet would then address messages to your users in the typical SMTP format—something like user@organization.com. (You will learn how this works in Chapter 13, “Connecting Routing Groups.” For now, you need to understand that the way you name the objects in your organization has fairly far-reaching effects.)

Defining Routing Groups

In general, you want to keep the number of routing groups in your organization as low as possible. If you can get away with having just one routing group, you should do so. Many of the communications between servers in a group, such as message transfers, are configured and happen automatically, greatly reducing administration on your part. However, there are also many good reasons to use multiple routing groups. This section covers some of these considerations.

Geographic Considerations

If your company is spread over two or more geographic regions, you might want to implement a routing group for each region. The primary reason for doing so is to help manage network bandwidth consumption. A single routing group is easy to set up because much of the communication between the servers in a routing group occurs automatically. Unfortunately, this automatic communication consumes a considerable amount of bandwidth, which grows with the size of the routing group. If your network contains WAN links, which typically have a smaller amount of bandwidth available, it is best to divide the organization so that an Exchange routing group does not span a WAN link, because Exchange Server provides ways to limit and schedule the traffic between routing groups.

Network Considerations

Several physical factors determine the possible boundaries of a routing group. All Exchange servers within a routing group must be able to communicate with one another over a network that meets certain requirements:

-

Common Active Directory forest All servers within a routing group must belong to the same Active Directory forest.

-

Persistent connectivity Because of the constant and automatic communication between Exchange servers within a routing group, these servers must be able to communicate using SMTP over permanent connections—connections that are always on line and available. In addition, all servers within a routing group must be able to contact the routing group master at all times. If you have network segments that are connected by a switched virtual circuit (SVC) or a dial-up connection, you must implement separate routing groups for those segments.

-

Relatively high bandwidth Servers in a routing group require enough bandwidth on the connections between them to support whatever traffic they generate. Microsoft recommends that the connection between servers support at least 128 Kbps. Keep in mind that if a network link is heavily used, 128 Kbps will not be sufficient for Exchange Server traffic. The network link should have a fair amount of bandwidth available for new traffic generated by Exchange Server, if an Exchange routing group will span that link.

Routing groups in Exchange Server—like sites in Exchange Server 5.5—are based on available bandwidth. However, Exchange Server uses SMTP, which is more tolerant of lower bandwidths and higher latency. This capability means that you can group servers into routing groups that you could not have grouped into sites in Exchange 5.5. You might want to divide Exchange servers into multiple routing groups for a number of reasons:

-

The minimum requirements outlined previously are not met.

-

The messaging path between servers must be altered from a single hop to multiple hops.

-

The messages must be queued and sent according to a schedule.

-

Bandwidth between servers is less than 16 Kbps, which means that the X.400 Connector is a better choice.

-

You want to route client connections to specific public folder replicas since public folder connections are based on routing groups.

The most important factor to consider when planning your routing group boundaries is the stability of the network connection, not the overall bandwidth of the connection. If a connection is prone to failure or is often so saturated that the pragmatic effect is a loss of connectivity, you should place the servers that the connection serves in separate routing groups.

Be sure to have a Global Catalog server in each routing group and preferably in each Active Directory site. This arrangement decreases lookup traffic across your slower WAN links and makes the directory information for client lookups more available to your clients.

Planning Routing Group Connectors

After you’ve determined how many routing groups your organization will have and what the boundaries of those groups will be, you need to plan how those groups will be linked. Routing groups are linked by connectors that allow servers in the different groups to communicate. Exchange Server provides three connectors that you can use to link routing groups: the Routing Group Connector, the SMTP Connector, and the X.400 Connector. These connectors are covered in detail in Chapter 13. This section briefly describes the advantages and disadvantages of each connector.

Routing Group Connector

The Routing Group Connector (RGC) is used only to connect one routing group to another. The RGC is by far the easiest of the connectors to set up and, everything else being equal, is also the fastest. It has some of the strictest use requirements, however; it needs a stable, permanent connection that supplies relatively high bandwidth. SMTP is used as the native transport for the RGC.

The RGC works using bridgehead servers. A server in one routing group—a bridgehead server—is designated to send all messages to the other routing group. Other servers within the routing group send messages to the bridgehead server, which then sends the messages to a bridgehead server in the other routing group. That bridgehead server is then responsible for delivering the messages to the correct servers within the group. If you want, you can configure more than one bridgehead server in a routing group, for the purposes of fault tolerance and load balancing. Bridgehead servers let you control which servers transfer messages between routing groups.

SMTP Connector

The SMTP Connector can be used to connect two Exchange routing groups or to connect an Exchange organization to a foreign messaging system. It can also be used to connect two Exchange routing groups over the Internet. The SMTP Connector allows finer control over message transfer than the RGC, including the ability to authenticate remote domains before sending messages, to schedule specific transfer times, and to set multiple permission levels for different users on the connector.

X.400 Connector

The X.400 Connector can be used to connect two routing groups or to connect an Exchange organization to a foreign X.400 messaging system. In connecting two routing groups, the X.400 Connector is generally slower than an RGC because of additional communication overhead. Since the RGC allows scheduling and maximum message sizes, you most likely will not use an X.400 Connector to connect two Exchange routing groups.

Multiple Messaging Connectors

Generally speaking, it is simplest to configure only one connector between any two routing groups. You can, however, configure multiple connectors. Multiple connectors can be used to provide fault tolerance in case one connector fails or to balance the messaging load over different network connections. For example, you could create two X.400 Connectors between the same two sites using different pairs of messaging bridgehead servers. If one connector went down (most likely because one of the bridgehead servers in that pair failed), the other connector (and its designated bridgehead servers) would remain up.

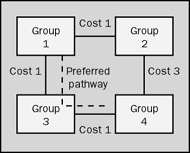

A cost value is assigned to each connector you create on a routing group. Cost values range from 0 through 999. (There is no cost value assigned to the SMTP connector itself—only to the address spaces associated with the SMTP Connector.)

A messaging connector with a lower cost is always preferred over one with a higher cost. This approach allows you to designate primary and backup connectors between routing groups. When Exchange determines which connector it should use to send a message, it takes into account the cumulative cost of the entire messaging path. In Figure 6-2, for example, a message could move from group 1 to group 4 by being transmitted either through group 2 or through group 3. The path through group 2 has a cumulative cost of 4, whereas the path through group 3 has a cumulative cost of 2. Thus, Exchange Server will prefer the path through group 3 because it has the lowest cost.

Figure 6-2: Using costs to determine message routing.

Use multiple connectors whenever the physical networking between routing groups is unreliable. For a small or medium-sized network with high-bandwidth links between routing groups, having a single connector between groups provides a consistent messaging pathway. This consistency is valuable in developing an accurate picture of network traffic and in troubleshooting message delivery problems. In medium to large networks that have inconsistent traffic patterns or restricted bandwidth availability as well as multiple, redundant links between groups, using multiple connectors between groups for backup or load balancing can enhance the messaging system’s reliability.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 254

- Challenging the Unpredictable: Changeable Order Management Systems

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Context Management of ERP Processes in Virtual Communities

- Distributed Data Warehouse for Geo-spatial Services

- Relevance and Micro-Relevance for the Professional as Determinants of IT-Diffusion and IT-Use in Healthcare

- Structures, Processes and Relational Mechanisms for IT Governance

- Integration Strategies and Tactics for Information Technology Governance

- A View on Knowledge Management: Utilizing a Balanced Scorecard Methodology for Analyzing Knowledge Metrics

- Governance in IT Outsourcing Partnerships

- The Evolution of IT Governance at NB Power