Chapter XVI Turning Web Surfers into Loyal Customers: Cognitive Lock-In Through Interface Design and Web Site Usability

XVI Turning WebSurfers into Loyal Customers Cognitive Lock In Through Interface Design and Web SiteUsability

Manlio Del Giudice

University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy

Abstract

This chapter focuses on how Web site elements (e.g., interface design, tools provided, usability, information, etc.) can influence customer satisfaction and prevent switching behaviors, acting as positive switching costs. Some switching barriers can be seen as more positive in their nature and others as more negative. Then, psychologically, customers remain loyal to a supplier either because they want to or they have to. Following this approach, the aim of this chapter, therefore, is to highlight the strategic role that positive switching costs, stemming from a well-designed Web site, play both in traditional sectors and in the expanding networked environment. Furthermore, we develop an empirical customer switching cost framework in an effort to improve understanding and management of this phenomenon.

Introduction

Does Look and Feel Really Lack? A Glance to the Shopping Experience in a Digital Economy

E-commerce is growing rapidly and has penetrated almost all industries. Given its enormous potential, the number of electronic stores has increased at an unprecedented rate during the last five years. Theory seems to support the prediction that online shopping will keep rising in the future, as online search engines and various intelligent agents can dramatically reduce search costs associated with purchase decisions (Alba et al., 1997; Bakos, 1997; Brondoni, 2002a, 2002b; Maggioni, 2000). However, online shopping lacks “look-and-feel” (Figueiredo, 2000) and hence evaluation of product attributes for firms online can be still difficult. Indeed, while in off-line commerce it is often the salesperson that influences the buyer’s trust in the seller (Doney & Cannon, 1997) thus inducing loyal behaviors, in the Internet context it is the Web site that should do that (Lohse & Spiller, 1998; Del Giudice & del Giudice, 2003). That’s why nowadays the assessment of the effectiveness of e-commerce Web sites is of critical importance to online retailers. As e-commerce begins to mature, the ability to retain customers is the only way an e-business can survive (Agrawal & Karahanna, 2000; Agrawal et al., 2001; Chen & Hitt, 2002). Apparently the quality of the online customer experience that effectively-designed Web sites create not only has a positive effect on the economic performance of a firm, but also possesses the potential to create a unique and sustainable competitive advantage for Internet-based sellers, by turning Web crawlers into loyal customers (Rajgopal et al., 2001). In fact, since quality service is something customers generally expect vendors to provide (Parasuraman et al., 1985; Zeithaml et al., 1996), high quality service through interface design and Web site usability should arguably build customer loyalty, as a recent study with customers of online vendors indicates (Reichheld & Schefter, 2000). Overall, Web sites’ design elements influence perceptions of Web site complexity, and perceived complexity, in turn, has a direct influence on communication efficiency and effectiveness and, thus, on purchase intentions.

Wanting to be Loyal or Having to be Loyal?

Following those premises, this chapter focuses on how Web site elements (interface design, tools provided, usability, information, etc.) can influence customer satisfaction and prevent switching behaviors, acting as positive switching costs. Jones et al. (2000) mention that some switching barriers can be seen as more positive in their nature and others as more negative. Psychologically, it should make a great difference whether one maintains a relationship because of a perception that the supplier is superior in services and products (a positive reason), or because it is too expensive to leave the supplier, there is a monopoly on the market or the supplier is powerful (negative reasons). The main rationale behind the distinction between positive and negative reasons is similar to Lund’s idea of barrier push vs. positive pull (Lund, 1985); a supplier that retains its customers through positive pull rather than through barrier push is likely to develop a stronger position vis-à-vis its customers. Only a few empirical studies, however, investigate how various kinds of switching costs affect satisfaction with suppliers, repurchase intentions, cognitive loyalty and the relationships between these variables (Jones et al., 2000). The purpose of this chapter is to make some distinctions as to the character of switching barriers, and to formulate and empirically test hypotheses regarding the role of positive switching costs stemming from Web sites’ elements in the context of satisfaction, repurchase intentions and cognitive loyalty. Particularly, a dynamic framework of cognitive lock-in is then discussed. The aim of this chapter, therefore, is to highlight the strategic role that customer switching costs play both in traditional sectors and in the expanding networked environment, to expand and improve upon the conceptualization of the force, and to develop a customer switching cost framework in an effort to improve understanding and management of this phenomenon. The chapter is organized as follows. In the first part of this work we focus on the literature review (the strategic importance of customer switching costs by analyzing their role in the strategy, economics, and marketing literature). Next we explore why switching costs are even more strategic in today’s digital environment. We discuss, then, and expand upon the concept of customer switching costs in an effort to provide a more complete and useful conceptualization. Next we discuss the key issues and challenges involved in managing switching costs and we attempt to develop a switching cost framework to help improve understanding and management of these challenges. Finally, we discuss key implications of the work and offer our conclusions.

Strategic Importance of Switching Costs A LiteratureReview

The strategic importance of switching costs has been recognized and researched by several academic disciplines, primarily economics and marketing (Porter, 1980, 1985, 2001; Rumelt, 1987; Lieberman & Montgomery, 1988; Klemperer, 1987a, 1987b, 1995; Kotler, 1997; Shapiro & Varian, 1999; Hax & Wilde II, 1999, 2001). In the economics literature several researchers have studied the role of switching costs (Porter, 1980, 1985; Katz & Shapiro, 1985; Farrell & Saloner, 1986; Farrell & Gallini, 1988; Farrell & Shapiro, 1988; Klemperer, 1987a, 1987b, 1995; Shapiro & Varian, 1999; Shapiro, 2000). Klemperer uses theoretical models to show that in certain cases consumers face switching costs after choosing among products that were ex ante undifferentiated. As a result, in subsequent purchases rational consumers display brand loyalty when faced with a choice between functionally identical products. In their book Information Rules (1999), Shapiro and Varian emphasize that “switching costs are the norm, not the exception, in the information economy.” In the marketing field, as well, switching costs are identified as playing a key role in the process of creating strong customer loyalty (Kotler, 1997). This process, known as relationship marketing, involves all of the actions a firm can take to better understand and satisfy its customer. Jones et al. (2000) defined, then, a switching cost as any factor which makes it difficult or costly for consumers to change providers. Ping (1993, 1997, 1999), following Johnson’s (1982) concept structural constraints, uses the term structural commitment as a measure of the extent to which the customer has to remain in a relationship. Ping argues that structural commitment includes alternative attractiveness, investment in a relationship and switching cost. Fornell (1992), without proposing a formal definition of the concept, provides a list of factors that can constitute such barriers (i.e., if they are prevalent they will hinder customers trying to defect from a relationship): search costs, transaction costs, learning costs, loyal customer discounts, customer habit, emotional cost, cognitive effort and financial, social and psychological risk.

Is Web Site Usability a Switching Cost The Role of WebSite s Elements to Generate Switching Barriers

There is ongoing debate over the role of switching costs in the Internet environment, where switching costs are often referred to as friction. According to Hax and Wilde II (2001), the networked environment has altered the nature of competition by amplifying the relationship between customers and suppliers. While switching costs are not a new force, they argue that the combination of a common digital language and the reach of the network make switching costs more strategic and powerful in the new economy. They state that “the Internet is all about bonding,” and that as a result we can expect more friction, or switching costs, not less in the new economy. Shapiro and Varian (1999) argued that frictions do not disappear in the Internet environment, they just mutate into new forms. This enables firms to convert traditional markets into lock-in markets by creating information-enabled or synthetic switching costs, for example loyalty programs. Firms are also expanding their reach and providing more personalized information and products. In addition, while switching costs based on equipment tend to decline as equipment wears out or superior performing equipment comes along to replace it, switching costs based on information (such as Amazon.com’s customer databases or its filtering tools or the shopping masks allowing “one-click shopping”) never wear out. In fact, they tend to strengthen over time given that the more information a company has about the client, the better the company can serve the client and thus further increase switching costs. In an empirical study by Amit and Zott (2001), switching costs are found to play an important role in e-businesses’ ability to create value. The authors carry out multiple case studies on U.S. and European firms and conclude that the four value creators of e-business are: (1) efficiency, (2) novelty, (3) complements, and (4) lock-in. Their data reveal that firms achieve lock-in as a result of switching costs and network externalities, and that the strategies implemented to manage lock-in include loyalty programs, establishing dominant design proprietary standards, establishing trustful relationships, learning, customization and personalization, and virtual communities. It is important to recognize, however, that not all of the changes in the new economy are leading to an increase in switching costs. The same changes in technology that provide firms with opportunities to create new switching costs are enabling customers and competitors to reduce traditional ones. For example, the traditional trade-off between richness (depth and detail of information) and reach (number of customers firms can reach and number of products they can offer) is being blown up (Evans & Wurster, 1999). These authors explain that information is being separated from things and that this information is now accessible to millions of people who are communicating through universal, open standards. This connectivity is critical, they argue, because key strategic elements such as brand identity, customer loyalty, and switching costs all rely on various types of information. They argue that traditional value chains will deconstruct because better informed customers will find it easier to switch suppliers, thus reducing traditional advantages such as vertical integration (one-stop shopping) or established relationships. The blow-up of the tradeoff between richness and reach leads to several important changes — reductions in search costs, reductions in transaction costs, reductions in interaction costs, reductions in asymmetries of information, and an increase in choice. Each of these changes causes bargaining power to shift from sellers to buyers (Bakos, 1997; Butler et al., 1997; Evans & Wurster, 1999; Porter, 2001). New infomediaries, navigators, and online communities further promote this shift in power by providing customers with more detailed, timely, and objective information, and allowing larger numbers of buyers and sellers to interact with one another (Armstrong & Hagel III, 1996; Evans & Wurster, 1999; Hagel III & Singer, 1999). Hartman and Sifonis (2000) go so far as to say that in today’s competitive environment traditional customer relationship management is out because it is the customer who now manages the relationship. Therefore, customers must be listened to and valued, and if the business does everything right, only then might the customer agree to be served. Shapiro and Varian (1999) recognize that new technologies can shift bargaining power by reducing search costs and enabling sellers to send out more messages and reach wider audiences. But they caution that switching costs may remain prohibitive because customers still have to filter through and evaluate all of the offers. Yoffie (1999) provides an additional message of caution to the frictionless proponents by claiming that because of the bewildering pace of the Internet, the traditional core elements of competitive advantage — such as leadership, innovation, quality, customer lock-in, and switching costs — may become even more important. Brynjolfsson and Smith (2000) support Yoffie’s claim in a study on Internet price dispersion among commodity goods. The authors found that while many dimensions of friction do decline in the Internet environment, other friction creating factors such as trust, brand, and awareness may even become more important on the Internet. In this section we have shown that customer switching costs take on an increasingly strategic role in the expanding networked environment. Some of the researchers reviewed here claim that switching cost opportunities are declining, while others argue that switching costs are actually increasing in variety and strength as a result of the Internet. We believe that both arguments are valid. On the one hand, several traditional sources of switching costs have been reduced or in some cases even eliminated because of the characteristics of the networked environment. At the same time, some new switching cost opportunities have been created and certain traditional ones have become much more powerful in the changing environment. Because both increases and decreases in switching costs are taking place, and because of their potential impact on firm performance, recognizing and understanding these changes is critical for successful strategic decision making in today’s competitive environment.

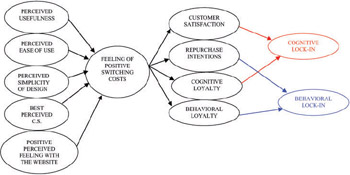

Following this approach we here discuss a dynamic model of customer loyalty for a digital environment, where: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and Web site usability, perceived simplicity of Web site design and Web site complexity, best perceived customer service and positive perceived feeling with the Web site (we will refer to those variables as the 5Ps) are seen as antecedents of the independent variable of the model, the customer perceived feeling of positive switching cost stemming from the Web site. As well we hypothesize that positive perceived switching costs are strongly correlated with a deeper customer satisfaction stemming from the online shopping experience, with a stronger repurchase intention and finally with a greater cognitive and behavioral loyalty. Moreover, we propose that customer satisfaction stemming from the online shopping experience and cognitive loyalty is likely to be related to cognitive lock-in strategies; whereas repurchase intention and behavioral loyalty are likely to be related with behavioral lock-in strategies. Figure 16-1 shows the hypothesized model.

Figure 16-1: Positive Switching Costs’ Model: Its Antecedents and Its Consequences

Perceived switching costs are consumer perceptions of the time, money, and effort associated with changing service providers. Such costs may entail search costs resulting from the geographic dispersion of service alternatives, as well as learning costs resulting from the customized nature of many service encounters (Guiltinan, 1989). As the perceived costs of an activity increase, the likelihood of consumers engaging in such behavior should diminish. Switching costs by making customer defection difficult or costly are important because they may generally foster greater retention. Interestingly, although numerous studies support the importance of customer satisfaction in the retention process, the relationship between these variables often evidences considerable variability. As just one example, Anderson and Sullivan (1993) found t-values for the satisfaction-repurchase intention relationship ranging from 1.1 to 13.1. Such variability highlights the possibility that: (1) retention may depend on additional factors such as switching costs, and (2) the relationship between satisfaction and retention may be contingent on switching costs arising in the context. The current study develops and tests a model of customer cognitive loyalty that incorporates such contingencies between customer satisfaction and switching barriers. Particularly we hypothesized and tested whether the 5Ps are likely to be possible antecedents of the customer perception of positive switching costs online. Before discussing the results of our empirical analysis, we would like firstly to introduce the 5Ps, switching costs of the Web site.

Which Positive Switching Costs? The 5PS Model

Perceived Usefulness

Perceived usefulness refers to the dynamic nature of the engagement that occurs between a supplier and its customers through the Web site (i.e., contact interactivity). Even if several studies have highlighted the importance of interactivity and perceived usefulness to customer loyalty (Deighton, 1996; Watson, Akselsen & Pitt, 1998), lack of interactivity is still a problem for a lot of Web sites (they are often hard to navigate, provide insufficient information, etc.). Perceived usefulness is often seen as the availability and effectiveness of customer support tools on a Web site, and the degree to which communication with customers is facilitated. It enables a search process that can quickly locate a desired product or service, thereby replacing dependence on detailed customer memory, but, also dramatically increases the amount of information that can be presented to a customer (Deighton, 1996; Watson, Akselsen & Pitt, 1998).

Perceived Ease of Use

This positive switching cost refers to the extent to which a customer feels that the Web site is simple, intuitive and user friendly. Accessibility of information and simplicity of the transaction processes are important antecedents to the successful completion of transactions. The quality of the Web site and the customer feeling of perceived ease of use are particularly important, since they represent the central or even the only interface with the marketplace (Palmer & Griffith, 1998). According to Schaffer (2000), 30% of the consumers who leave a Web site without purchasing anything act so because they are unable to find their pathway through the Web site. Sinioukov (1999) suggested that enabling customers to search for information easily and making the information readily accessible and visible is the key to creating a successful e-business. Cameron (1999) pointed out that a number of factors render a Web site inconvenient from a user’s perspective. In some cases, information may not be accessible because is not in a logical place, or is buried too deeply within the Web site. In other cases, information may not be presented in a meaningful format; finally, needed or desired information may be completely absent.

Perceived Simplicity of Web Site Interface Design

As mentioned earlier, Web sites’ design elements influence perceptions of Web site complexity, and perceived complexity, in turn, has a direct influence on communication efficiency and effectiveness and, thus, on purchase intentions. Moreover, it has been shown that perceived complexity in a Web site is related to communication effectiveness (O’Guinn et al., 2000; Zinkhan & Blair, 1984) and that usually customers respond more favorably toward Web sites of moderate complexity (Berlyne’s theory, for example, predicted an inverse, curvilinear relationship between medium complexity and communication effectiveness). Creative Web site interface design can help a supplier build a positive reputation and characterization for itself in the mind of customers. The perceived simplicity of Web site interface design and its positive impact as a switching cost on loyalty and retention has to be evaluated through the overall image the online firm projects to the customers through the use of inputs such as text, style, graphics, colors, logos, slogans or themes on Web site. Web site design, even with its simplicity, plays a key role: Web sites can be rather impersonal and boring to deal with in the absence of the person-to-person interaction that pervades conventional brick-and-mortar marketplaces (beyond general presentation and image, Web sites can use unique characters or personalities to enhance site recognition and recall (Henderson & Cote, 1998): such coded stimuli can positively impact customer attitudes).

Best Perceived Customer Service

This switching cost deals with the ability of an online firm to develop a quick and strong customer service through the Web site and to tailor products, services and the transactional and shopping environment to individual customers. A survey by NetSmart Research indicated that 83% of Web surfers are frustrated or confused when navigating sites (Lidsky, 1999). By personalizing its site and bettering the customer service, an online firm can reduce this frustration. A strong customer service through the use of collaborative masks, filtering tools, cookies, log files, simplified pathway, are key factors (they can signal high quality and lead to a better real match between customer and product. Finally, individuals are able to complete their transactions more efficiently when the customer service is well built. The advantages of a good customer service make it appealing for customers to visit the Web site again in the future, instead of switching to another site.

Positive Perceived Feeling with the Web Site

Schaffer (2000) argued that a convenient Web site provides a short response time, facilitates fast completion of a transaction, and minimizes customer effort. Because of the nature of the medium itself, online customers have come to expect fast and efficient processing of their transactions. If customers are stymied and frustrated in their efforts to seek information or consummate transactions, they are less likely to come back (Cameron, 1999). A Web site that is logical and convenient to use will also minimize the likelihood that customers make mistakes and will make their shopping experience more satisfying. A perceived general positive feeling with the Web site make appealing the online shopping experience, thus inducing the customer to return.

In the following section we will present the results of our empirical study.

Empirical Results

Model s Hypotheses

As mentioned earlier, in the first part of the model (focused on switching costs’ antecedents) we hypothesize that:

H1: The 5Ps are positively related to perceived positive switching costs

Following this approach, we suppose (in the second part of the model, focused on the consequences of the customer perception of positive switching costs) that:

H2: Perceived positive switching cost are positively associated with customer satisfaction, repurchase intentions, cognitive and behavioral loyalty

H3a: Customer satisfaction and cognitive loyalty (in a digital environment) are positively associated with cognitive lock-in strategies

As well as:

H3b: Repurchase intentions and behavioral loyalty (in a digital environment) are positively associated with behavioral lock-in strategies

Research Methodology

Data Collection and Sampling Procedure

Our empirical analysis followed two steps: in the first part standard scale development procedures were followed in the development of the multidimensional switching costs scale. Scale items for the 5Ps were developed based on the guidelines suggested by Churchill (1979) and Gerbing and Anderson (1988). But also in-depth interviews with managers from a sample of 15 firms from IT (B2B) sector (three e-suppliers and 12 of their e-customers [that had experienced shopping online experiences with all the three esuppliers]) were conducted to define the scale items. A panel of five marketing faculty reviewed the items for clarity and face validity. Then item-total correlation, Cronbach’s Alpha and exploratory factor analysis were examined: thus the original items were refined and items not meaningfully were deleted. At this step (concluded the exploratory analysis) we were ready to administer the questionnaire to a sample of 180 e-customers [that had experienced shopping online from at least two of the original 3 e-suppliers]. The answering rate was quite high (about 86%). Our analysis followed mainly the structural equation modeling procedure.

Analyses and Results

The hypotheses were tested using multiple multivariate analysis methodologies (we used SPSS 11.0 and LISREL 8.54). As mentioned earlier, firstly we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to determine whether the scale items loaded as expected. We then calculated Cronbach’s alphas for the scale items to ensure that they exhibited satisfactory levels of internal consistency (Table 16-1). We refined the scales by deleting items that did not load meaningfully on the underlying construct and those that did not highly correlate with other items measuring the same construct.

|

PSC |

P1 |

P2 |

P3 |

P4 |

P5 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Positive Perceived Switching Costs (PSC) |

0.93 |

|||||

|

Perceived Usefulness (P1) |

0.67 |

0.84 |

||||

|

Perceived Ease of Use (P2) |

0.62 |

0.69 |

0.79 |

|||

|

Perceived Simplicity of Web site Design (P3) |

0.73 |

0.65 |

0.61 |

0.87 |

||

|

Best Perceived Customer Service (P4) |

0.79 |

0.72 |

0.67 |

0.75 |

0.91 |

|

|

Positive Perceived Feeling with the Web site (P5) |

0.79 |

0.63 |

0.72 |

0.84 |

0.62 |

0.85 |

|

*Cronbach’s Alpha for the constructs are given in red colour in the diagonal elements. |

Antecedents of Perceived Positive Switching Costs Feeling

Hypothesis H1 refers to the impact of the 5Ps on the customer perceived feeling of positive switching costs (during his online shopping expeditions), stemming from the Web site’s elements. To parsimoniously capture the joint impact of the 5Ps, we used the following multiplicative model:

PSC = g0 * P1g1 * P2g2 * P3g3 * P4g4 * P5g5 (1)

Where: PSC = customer perceived feeling of positive switching costs; P1 = perceived usefulness; P2 = perceived ease of use; P3 = perceived simplicity of Web site interface design; P4 = best perceived customer service; P5 = positive perceived feeling with the Web site. Equation (1) was linearized by logarithmic transformation and the log-transformed model was estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS). Correlations between the variables are reported in Table 16-1.

Parameter g0 is the intercept, and parameters g1 to g5 capture the impact of the 5Ps on PSC Results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 16-2. A summary consideration of the results indicates that all the parameters estimated are significant at p < .05, and in the predicted direction. The adjusted R2 of the model is 0.73. We calculated the variance inflation factor to check for multicollinearity: the average VIF is 2.66, ranging from 2.11 and 3.21, well below the recommended cutoff of 10 (Neter, Wasserman & Cutner, 1985). Thus our hypothesis (H1) that the 5Ps are positively related to customer feeling of positive switching costs stemming from Web site’s elements is supported. The elasticity of PSC respect to the 5Ps ranges from 0.07 for perceived ease of use to 0.42 for positive perceived feeling with the Web site.

|

Independent Variables |

Parameter Estimate |

Standard Error |

T Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Constant |

0.3984 |

0.0723 |

4.985 |

|

Perceived Usefulness (P1) |

0.1547 |

0.0406 |

4.321 |

|

Perceived Ease of Use (P2) |

0.0731 |

0.0324 |

3.214 |

|

Perceived Simplicity of Web site Design (P3) |

0.1532 |

0.0256 |

5.332 |

|

Best Perceived Customer Service (P4) |

0.1634 |

0.0452 |

6.845 |

|

Positive Perceived Feeling with the Web site (P5) |

0.4187 |

0.0321 |

7.053 |

|

*t value is significant at <.05 confidence level. |

Consequences on Customer Satisfaction, Repurchase Intentions, Cognitive and Behavioral Loyalty

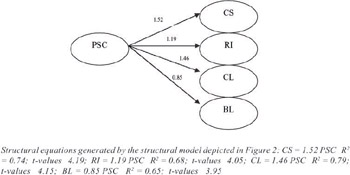

Hypotheses H2 focuses on the consequences of customer-perceived positive switching costs. To test the impact of PSC on customer satisfaction (= CS), repurchase intentions (= RI), cognitive loyalty (CL) and behavioral loyalty (BL), the hypotheses were tested by the use of structural equation modeling (SEM, this time using LISREL 8.54); the path diagram, the separate structural equations and regression analyses with the latent variable scores will be reported. The collected evidence from all these analyses will be used for the conclusion regarding the stated hypothesis. The path diagram (Figure 16-2) shows that PSC have a positive direct effect, as hypothesized, on all the considered four dimensions. All estimates have t-values larger than three and are thus statistically significant. The structural equations (reduced models) as well as the multiple regression analysis (MRA) confirm this result, by generating a high R2 (0.87).

Figure 16-2: Relationship between customer perceived feeling of positive switching costs and customer satisfaction (CS), repurchase intentions (RI), cognitive loyalty (CI), behavioral loyalty (BI)

Although c2 measure should show a lower value (c2 = 12.52, df = 172, p < 0.005), since c2 is very sensitive to sample size, a large number of other indices indicate a good fit of the model. Table 16-3 shows some of those indices along with reported guidelines for a good model.

|

Fit Index |

Guidelines |

Model values |

|---|---|---|

|

c2 |

12.52, df = 172, p < 0.005 |

|

|

CMIN/DF |

2 |

2.563 |

|

NFI |

NFI>0.9 |

0.975 |

|

TLI |

TLI>0.9 |

0.975 |

|

GFI |

GFI>0.9 |

0.947 |

|

AGFI |

AGFI>0.9 |

0.911 |

|

Delta 2 |

Delta 2>0.9 |

0.982 |

Possible Correlates with Cognitive and Behavioral Lock In Strategies

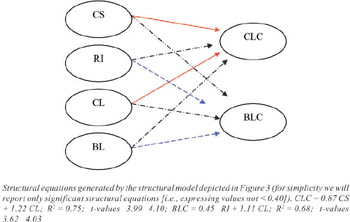

Hypotheses H3a and H3b focus instead on the possible correlation between CS, RI, CL, BL and cognitive and behavioural strategies in a digital environment. In order to test their possible correlation, the hypotheses were also tested in this case by the use of SEM. The path diagram, the separate structural equations and regression analyses with the latent variable scores are reported below. The path diagram (Figure 16-3) shows, as hypothesized, that customer satisfaction and cognitive loyalty are correlated higher with cognitive lock-in strategies (than with behavioral lock-in), whereas repurchase intentions and behavioral loyalty better correlate with behavioral lock-in strategies (than with cognitive ones). All estimates have t-values larger than three and are thus statistically significant. The structural equations (reduced models) as well as the multiple regression analysis (MRA) confirm this result, by generating a high R2 (0.76).

Figure 16-3: Relationship between customer satisfaction (CS), repurchase intentions (RI), cognitive loyalty (CI), behavioral loyalty (BI) and cognitive (CLC)/behavioral (BLC) lock-in strategies (For simplicity we will show only the significant values [values <0.40 are omitted]. We report in large dashed arrows and irregular dashed arrows the significant pathways.)

Also in this case c2 measure should show a lower value (c2 = 14.73, df = 165, p < 0.005). But a large number of other indices indicate a good fit of the model (Table 16-4 shows some of those indices along with reported guidelines for good model.).

|

Fit Index |

Guidelines |

Model values |

|---|---|---|

|

c2 |

14.73, df = 165, p < 0.005 |

|

|

CMIN/DF |

2 |

|

|

NFI |

NFI>0.9 |

|

|

TLI |

TLI>0.9 |

|

|

GFI |

GFI>0.9 |

|

|

AGFI |

AGFI>0.9 |

|

|

Delta 2 |

Delta 2>0.9 |

Managerial Implications and Future Trends

Consistent with prior research, customer satisfaction should remain a primary strategic focus of service providers due to its strong impact on customer retention. The practical implications of switching costs may, however, not be so straightforward. One possible conclusion is that online firms should build up various switching costs (following possible guidelines stemming from 5Ps analysis) through their Web sites’ elements so as to retain existing customers. Such a recommendation seems most fitting for firms who generally satisfy their customers but want some sort of “insurance” against possible defections (Tax, Brown, & Chandrashekaran, 1998). We have not to forget that in digital economy every supplier is a “click away.” Such “negative” barriers may do more harm than good in the long run. Positive switching costs through Web site usability provide intrinsic benefits may be less likely to create feelings of entrapment and, therefore, less likely to result in sabotage-type behaviors. We have argued in this chapter that customer switching costs play a key role in competitive strategy for online firms, aiming at changing simple Web surfers into strongly loyal customers. Of course the role of switching costs is changing in important ways as a result of the increasingly networked environment. We also claim that managing switching costs on a Web site is much more complex than simply raising switching costs. We know that they are a very dynamic force and that managing them involves many difficult challenges: managers need to understand what types of switching cost opportunities are available through their Web sites’ elements. They need to try and understand the potential strength, or degree, of the different switching cost opportunities they plan to pursue; they need to recognize how switching costs are changing as a result of the increasingly networked environment; they need a long-term strategic approach (focused mainly on cognitive lock-in than on behavioural ones) for developing switching costs; they need to innovate or quickly adapt to changes to ensure the maintenance of switching costs over time. While these new switching costs do not arise solely due to the characteristics of the networked economy, we argue that they are definitely more prominent because of this changing environment. Furthermore we argue that the changing environment is affecting almost all switching costs in important ways that must be recognized. Whether or not firms can or want to capitalize on these changes, at least they need to be aware of them. Finally, the idea of different kinds of online switching costs goes well beyond the classic case of “lock-in.” Lock-in may be what all firms are striving for, but in reality it is a situation few firms still achieve.

Finally, our chapter, by choosing the online environment as an example, tries to react to the matter that switching costs are still often viewed in the literature as an abusive or opportunistic behavior on the part of suppliers and as a problem for captive customers, not distinguishing between positive and negative switching barriers. Obviously the potential for suppliers to behave opportunistically towards customers with high switching costs will always exist. However, the rapid pace and scope of change in today’s competitive environment increase the opportunities for revolutions to occur that can unlock customers. As a result, today’s opportunistic firms run the risk of being lockedout by customers in the future.

Conclusions and Cues for Further Research

In this chapter we have attempted to improve the understanding and management of an important strategic element known as customer switching costs. By reviewing the strategy, economics, and marketing literature, we show that researchers have long acknowledged the importance of the phenomenon. In addition, we discuss how switching costs appear to be changing as a result of the increasingly networked environment. Despite broad recognition of its important and changing strategic role, we find a lack of coherence and comprehensiveness regarding the conceptualization of switching costs and the tools or models provided to manage the force. To address these issues we attempt to build upon and refine the term’s conceptualization and we developed an integrated switching cost framework, mainly focused on positive switching costs stemming from Web sites’ elements. We believe that the switching cost framework provides a powerful and insightful lense for managers pursuing competitive advantage in today’s networked environment. But, despite the importance of a Web site, the process of designing high quality Web sites for e-commerce is still more of an art than a science. E-commerce companies still rely largely on intuition when it comes to designing their Web sites. To make matters worse, design changes and their impacts are not tracked, making it impossible to measure the benefits of Web site design (Wallach, 2001). This situation brings to the foreground the importance of value-driven evaluation and design of e-commerce Web sites. However, e-businesses are facing difficulties due to the lack of proven tools and methods for accomplishing this. Customers expect a certain level of service to accompany their purchases of goods and services. At the same time, in a digital environment, customers expect to enjoy a satisfying online shopping experience: changing Web surfers into loyal customers has thus become the final goal of many online firms. Moreover, elements that contribute to customer satisfaction and to the creation of a customer feeling of positive switching costs and thereby lead to repeat purchases include availability of sufficient information, ease of use interfaces, general Web site usability, simplicity in the interface design, deep customer service, etc. Yet, the Web-based retail shopping experience may differ from conventional shopping in several ways, possibly resulting in differing customer satisfaction elements. With the explosive growth of conventional marketers offering their products and services online, as well as new businesses proliferating solely for online marketing, research is warranted to examine the key factors in customers’ shopping experiences that contribute to customer satisfaction with shopping via this new marketing channel. Research that contributes to an understanding of customer experiences with online shopping has important implications for researchers as well as business managers and information systems managers (Adam et al., 1999). Although marketers are beginning to understand the innovative strategies that will attract visitors to Web sites (Hoffman et al., 1995), little is known about the factors that make Web use a compelling customer experience or about the key customer satisfaction outcomes of this compelling experience. Researchers have been trying to develop and test a general model of the online customer experience (Novak and Hoffman, 1997; Novak et al., 2000). However, few studies have been conducted to test the relationship between retail Web site presentations and key elements of customers’ actual online shopping experience (in terms of site design effectiveness for satisfactory customer shopping experiences). Conventional marketing research has illustrated the relationship of customer service variables with customer outcomes such as customer satisfaction (Bolton & Drew 1991; Fram & Grady 1995; Zeithaml & Berry 1993). Customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction is the core concept of marketing and information systems (Kosiur, 1997). It follows that lack of satisfaction with a Web site would lead to customer intention not to purchase from that site. Accordingly, this research attempts to analyze some elements of online shopping experiences that influence the shopper’s satisfaction with the online shopping experience, leading the shopper to purchase from that site or alternatively to switch to another site.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank managers of all the businesses contacted who have allowed the collection of empirical data from which the present work has stemmed. My thankfulness also to the two anonymous reviewers who through their comments and advice have greatly contributed to better the present work.

References

Adam, N. R., Dogramaci, O., Gangopadhyay, A., & Yesha, Y. (1999). Electronic commerce: Technical, business, and legal issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Agarwal, R., & Karahanna, E. (2000). Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Quarterly, 24(4), 665-694.

Agrawal, V., Arjona, L. D., & Lemmens, R. (2001). E-Performance: The path to rational exuberance. The McKinsey Quarterly, (1), 31-43.

Alba, J., Lynch, J., Weitz, B., Janiszewski, C., Lutz, R., & Sawyer, A. (1997). Interactive home shopping, consumer, retailer, and manufacturer incentives to participate in electronic marketplaces. Journal of Marketing, 61(3), 38-53.

Amit R., & Zott, C. (2001, June/July). Value creation in e-business. Strategic Management Journal, 493-520.

Anderson, E.W., & Sullivan, M.W. (1993, Spring). The antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms. Marketing Science, 12, 125-143.

Anderson, L. (2002, March). In search of the perfect Web site. Smart Business, 60-64.

Bakos, Y. (1997). Reducing buyer search costs: Implications for electronic marketplaces. Management Science, 43(12), 1676-1692.

Bendapudi, N., & Berry, L.L. (1996). Customers’ motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers. Journal of Retailing, 72, 223-247.

Brondoni, S.M. (2002). Global markets and market-space competition. Symphonia, 1.

Brondoni, S.M. (2002). Overture in corporate culture and market complexity. Symphonia, 2.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Smith, M.D. (2000). Frictionless commerce? A comparison of Internet and conventional retailers. Management Science, 46(4), 563-585.

Butler, P., Sahay, A., Mendonca, L., Manyika, J., Hanna, A., & Auguste, B. (1997). A revolution in interaction. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1, 4-23.

Cameron, M. (1999, November). Content that works on the Web. Target Marketing, 1, 22-58.

Chen, P.-Y. S., & Hitt, L.M. (2000). Switching cost and brand loyalty in electronic markets: Evidence from on-line retail brokers. In W.J. Orlikowski, S. Ang, P. Weill, H. C. Krcmar, & J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Information Systems, Brisbane, Australia, December 14-17 (pp. 134-144).

Churchill Jr., G.A. (1979, February). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 64-73.

Cronin Jr., J.J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992, July). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56, 55-68.

Deighton, J. (1996, November/December). The future of interactive marketing. Harvard Business Review, 74, 151-160.

Del Giudice M., & del Giudice, F. (2003). Locking-in the customer: How to manage switching costs to stimulate e-loyalty and reduce churn rate. In S.K. Sharma & J. Gupta (Eds.), Managing e-business of the 21st century. Heidelberg: Heidelberg Press.

Doney, P.M., & Cannon, J.P. (1997, April). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 35-51.

Evans, P., & Wurster, T.S. (1999). Blown to bits. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Farrell, J., & Gallini, N.T. (1988). Second-sourcing as a commitment: Monopoly incentives to attract competition. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 19(1), 123-137.

Farrell, J., & Saloner, G. (1986). Installed base and compatibility: Innovation, product preannouncements, and predation. The American Economic Review, 76(5), 940-955.

Farrell, J., & Shapiro, C. (1988). Dynamic competition with switching costs. RAND Journal of Economics, 19(1), 123-137.

Fornell, C. (1992, January). A national Customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56, 6-21.

Gerbing, D.W., & Anderson, J.C. (1988, May). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 186-192.

Hagel III, J., & Singer, M. (1999). Unbundling the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 77(2), 133-141.

Hartman, A., & Sifonis, J.G. (2000). Net ready: Strategies for success in the e-conomy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hax, A.C., & Wilde II, D.L. (1999). The delta model: Adaptive management for a changing world. Sloan Management Review, 40(2), 11-28.

Hax, A.C., & Wilde II, D.L. (2001). The delta project. New York: Palgrave.

Henderson, P.W., & Cote, J.A. (1998, April). Guidelines for selecting and modifying logos. Journal of Marketing, 62, 14-30.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hoffman, D., Novak, T., & Chatterjee, P. (1995). Commercial scenarios for the Web: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 1(3). Special Issue on Electronic Commerce.

Johnson, M. P. (1982). Social and cognitive features of the dissolution of commitment to relationships. In S. Duck (Ed.), Personal relationships: Dissolving personal relationships (pp. 51-74). London: Academic Press.

Jones, M. A., Motherbaugh, D.L., & Beatty, S. (2000). Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 259-274.

Jones, T.O., & Sasser Jr., W.E. (1995, November/December). Why satisfied customers defect. Harvard Business Review, 88-99.

Katz, M.L., & Shapiro, C. (1985). Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. American Economic Review, 75, 424-440.

Klemperer, P. (1987a). Markets with consumer switching costs. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 375-394.

Klemperer, P. (1987b). The competitiveness of markets with switching costs. RAND Journal of Economics, 18(1), 138-150.

Klemperer, P. (1995). Competition when consumers have switching costs: An overview with applications to industrial organization, macroeconomics, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 62, 515-539.

Kosiur, D. (1997). Understanding electronic commerce. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press.

Kotler, P. (1997). Marketing management: Analysis, planning, implementation, and control (9th ed.). NJ: Prentice Hall.

Levinger, G. (1979). Marital cohesiveness at the brink: The fate of applications for divorce. In T. L. Huston (Ed.), Divorce and separation: Context, causes, and consequences (pp. 99-120). New York: Academic Press.

Lidsky, D. (1999, October). Getting better all the time: electronic commerce sites. PC Magazine, 17, 98.

Lieberman, M.B., & Montgomery, D.B. (1988). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 41-58.

Lohse, G.L., & Spiller, P. (1998). Electronic shopping: Quantifying the effect of customer interfaces on traffic and sales. Communications of the ACM, 41(7).

Lund, M. (1985). The development of investment and commitment scales for predicting continuity of personal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 2(2), 3-23.

Maggioni, V. (2000). Apprendere dalle strategie relazionali delle imprese: Modelli ed esperienze per le meta-organizzazioni. SINERGIE, 52.

Neter, J., Wasserman, W., & Kutner, M.H. (1985). Applied linear statistical models. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

Nielsen/Net Ratings. (2001). Retrieved from: http://www.nielsen-netratings.com

Novak, T., & Hoffman, D. (1997). New metrics for new media: Toward the development of Web measurement standards. World Wide Web Journal, 2(1), 213-246.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D., & Yung, Y. (2000). Measuring the customer experience in online environments: A structural modeling approach. Marketing Science, 19(1), 22-42.

Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Palmer, J.W., & Griffith, D.A. (1998, March). An emerging model of Web site design for marketing. Communications of the ACM, 41, 44-51.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985, Fall). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 40, 41-50.

Ping, R. (1993). The effects of satisfaction and structural constraints on retailer exiting, voice, loyalty, opportunism, and neglect. Journal of Retailing, 69(3), 320-352.

Ping, R. (1997). Voice in business-to-business relationships: Cost-of-exit and demographic antecedents. Journal of Retailing, 73(2), 261-281.

Ping, R. (1999). Unexplored antecedents of exiting in a marketing channel. Journal of Retailing, 75(2), 218-241.

Porter, M.E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press.

Porter, M.E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: Free Press.

Porter, M.E. (2001). Strategy and the Internet. Harvard Business Review, 79(3), 63-78.

Rajgopal, S., Venkatachalam, M., & Kotha, S. (2001, April). Does the quality of online customer experience create a sustainable competitive advantage for e-commerce firms? (Working Paper), Seattle, WA: School of Business Administration, University of Washington.

Raphel, M., & Raphel, N. (1995). Up the loyalty ladder: Turning sometime customers into full-time advocates of your business. New York: Harper Business.

Reichheld, F. F., & Schefter, P. (2000). E-Loyalty: Your secret weapon on the Web. Harvard Business Review, 78(4), 105-113.

Rumelt, R. (1987). Theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship. In D.J. Teece (Ed.), The competitive challenge: Strategies for industrial innovation and renewal. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing.

Schaffer, E. (2000, May). A better way for Web design. InformationWeek, 784, 194.

Shapiro, C. (2000). Competition policy in the information economy. In E. Hope (Ed.), Competition policy analysis. Routledge: Studies in the Modern World Economy.

Shapiro, C., & Varian, H. (1999). Information rules. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Sinioukov, T. (1999, March). Mastering the Web by the book. BooTech the Magazine, 2, 50-54.

Sinioukov, T. (2000). Great expectations. Dealerscope Consumer Electronics Marketplace, 42(10), 38-39.

Souza, R., Manning, H., Sonderegger, P., Roshan, S., & Dorsey (2001). Get ROI From Design (Forrester Research Report). Cambridge, MA: Forrester Research.

Straub, D. W., Hoffman, D. L., Weber, B. W., & Steinfield, C. (2002a). Measuring e-commerce in net-enabled organizations: An introduction to the special issue. Information Systems Research, 13(2) 115-124.

Straub, D. W., Hoffman, D. L., Weber, B. W., & Steinfield, C. (2002b). Toward new metrics for net-enhanced organizations. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 227-238.

Taylor, S.A., & Baker, T.L. (1994). An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 70(2), 163-178.

Watson, R.T., Akselsen S., & Pitt, L.F. (1998, Winter). Attractors: Building mountains in the flat landscape of the World Wide Web. California Management Review, 40, 36-43.

Yoffie, D. (1996). Competing in the age of digital convergence. California Management Review, 38(4), 31-53.

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L.L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996, April). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60, 31-46.

Zona Research. (1999). Shop until you drop? A glimpse into Internet shopping success (Zona Assessment Paper). Redwood City, CA: Zona Research.

Section I - Consumer Behavior in Web-Based Commerce

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter II Information Search on the Internet: A Causal Model

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter IV How Consumers Think About Interactive Aspects of Web Advertising

- Chapter V Consumer Complaint Behavior in the Online Environment

Section II - Web Site Usability and Interface Design

- Chapter VI Web Site Quality and Usability in E-Commerce

- Chapter VII Objective and Perceived Complexity and Their Impacts on Internet Communication

- Chapter VIII Personalization Systems and Their Deployment as Web Site Interface Design Decisions

- Chapter IX Extrinsic Plus Intrinsic Human Factors Influencing the Web Usage

Section III - Systems Design for Electronic Commerce

- Chapter X Converting Browsers to Buyers: Key Considerations in Designing Business-to-Consumer Web Sites

- Chapter XI User Satisfaction with Web Portals: An Empirical Study

- Chapter XII Web Design and E-Commerce

- Chapter XIII Shopping Agent Web Sites: A Comparative Shopping Environment

- Chapter XIV Product Catalog and Shopping Cart Effective Design

Section IV - Customer Trust and Loyalty Online

- Chapter XV Customer Trust in Online Commerce

- Chapter XVI Turning Web Surfers into Loyal Customers: Cognitive Lock-In Through Interface Design and Web Site Usability

- Chapter XVII Internet Markets and E-Loyalty

Section V - Social and Legal Influences on Web Marketing and Online Consumers

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 180