Chapter XIV Product Catalog and Shopping Cart Effective Design

XIV Product Catalogand Shopping Cart Effective Design

Penelope Markellou

University of Patras, Greece

Maria Rigou

University of Patras, Greece

Spiros Sirmakessis

Technological Educational Institution of Messolongi, Greece

Abstract

The increasing integration of the Web into our trivial daily activities has become one of the prevailing trends in our days. Buying online is considered significantly more convenient than other modes of shopping, at least for some product categories. An online shop practices its potential for convenience and time efficiency when it becomes easily familiar. In many studies, consumers have indicated that their least favorite sites are those that fail to support a quick and easy shopping experience. Typically, these sites have repeatedly demonstrated significant design problems. This chapter is about identifying the design features that assure the effectiveness of two of the most crucial e-Shop components: the product catalog and the shopping cart.

Introduction

The online Product Catalog or Electronic Product Catalog (EPC) is e-Shops’ interactive front-end to potential customers. It offers a listing of all available products, combined with classification and retrieval support, in addition to interfaces to other e-Shop services. Formal definitions of electronic product catalogs vary in scope. Timm and Rosewitz (1998) define them as systems, which “...allow customers to browse through multimedia product representations and get relevant information concerning the product ...”, while Segev et al. (1995) describe them more broadly as “... a virtual gateway to a company through which customers obtain product information, order goods and services, make payment, access customer support, provide feedback, and participate in other corporate activities, …” A term very closely related to the electronic product catalog is what Nielsen et al. (2000a) reference as “Category Pages,” described as “…those mid-level pages in an e-Commerce website that help customers find the product listing pages – and thus the products they want to buy.” In fact, in this framework it is the combination of category pages along with the product listing pages that amount to the meaning of an electronic product catalog. Ceri et al. (1999) claim that electronic product catalogs can be seen as Web information systems that, in addition to laying emphasis on the presentation of products/services, contain some standard functionality regarding navigation, searching, selection and ordering of products (Koch & Turk, 1997).

Online product catalogs have their origin in paper-based product catalogs, which provide the convenience of home shopping and contain colorful and structured representation of products. Over time, product catalogs have changed their styles along with the carrier of information for which they were created and CD-ROM based catalogs came into play, which compared to their paper-based predecessors, offer sophisticated search functionality, as well as multimedia product presentation. Online product catalogs materialize the paper-based catalog metaphor[1] (Nielsen, 1993), but, due to the fact that they provide a much more powerful source of information on products, and that purchase decisions are usually made on this information, they are considerably more effective. As in a physical store, merchandise in an online store can be grouped within logical departments to make locating an item simpler. And while in most physical stores each product is kept in one place only, a Web store has the advantage of including a single product in multiple categories, just as easily (for example, running shoes can be listed as both “footwear” and “athletic gear”).

In its simplest, primitive form an electronic product catalog is a listing of goods and services. At the time of their first appearance on the Web, catalogs were simple static HTML lists. Operations such as editing an item’s listing, deleting or inserting an item required editing the HTML code of one or more pages. The large commerce sites handling big volumes of products, require sophisticated navigation aids and effective product organization, and thus use dynamic forms of product catalogs which retrieve contents from one or more databases. Dynamic catalogs can feature multiple photos of each item, detailed descriptions and a search mechanism that allows customers to check item availability. Yet surveys have indicated that the search for products in e-Shops is a cumbersome process. Customers have trouble finding the products they are looking for, and many abandon the online search before buying. This shows that there is great potential for online sales which is lost and that catalogs do not fulfill their task successfully. E-Customers have problems locating the right product(s) usually due to poorly structured product information and information overloaded sites offering no navigational support. In this chapter we examine catalogs from the perspective of information organization, management and retrieval, as well as usability. We will briefly review the functionalities typically provided by online product catalogs and propose a set of design guidelines for efficient information access and display.

Figure 14-1: Electronic product catalog on Amazon.com (accessed 10/23/2003)

The Shopping Cart (or “shopping basket,” “shopping bag,” “shopping sled,” or “wheelbarrow”) refers to a single page in an e-Shop, listing the items the customer has chosen to purchase. Like in the case of electronic product catalogs that serve as metaphors of their paper-based predecessors, the shopping cart is also a metaphor used for allowing customers to utilize their existing knowledge about how to buy products. The functionality typically supported by a shopping cart, allows customers to place products in it, remove one or more of them, or proceed to the checkout process. Figure 14-2 presents the shopping cart icons used by Amazon and by the Helcom e-Store (Kondilis et al., 2000). Regardless though of how successful the shopping cart metaphor has proven, for inexperienced users who are unfamiliar with e-Commerce practices, apart from the cart icon an accompanying label is also necessary.

Figure 14-2: Icons for shopping cart

A well-designed shopping cart can facilitate the transaction and encourage consumers to buy more (Robn, 1998), while poorly designed interface and functionality frustrate and prevent them from completing an online transaction. According to a BizRate.com survey[2], 78% of online buyers abandon their shopping carts. From them, 55% abandon carts before they enter the checkout process. Another 32% abandon their carts at the point of sale (e.g., when they are asked to fill in shipping and payment information). The reasons why shoppers abandon their carts vary and include (Hill, 2001) insufficient information, poor navigation, difficulty at handling, limited functionalities, confusing buttons or icons, time-consuming checkout processes, low quality of user interface, and more. According to Rewick (2000), the key is the understanding of customers’ psychology, needs, requirements and interests and how these factors are influenced by Web site design. However, abandonment does not always indicate specific design problems, as in many cases it is driven by the way consumers shop online (Smith, 2000). And nevertheless, products in a shopping cart (even in an abandoned one) convey a piece of valuable information: customer’s interest in specific products.

Effectiveness plays a central role in this chapter. For an online shop to be effective, it has to reassure user satisfaction. According to what HCI and more specifically UCD (User-Centered Design) experts dictate, e-Commerce should practice natural selection. People by nature will select the easiest way to accomplish a task (find what they want, buy what they want, or do what they want). According to Vredenburg et al. (2002), “Complexity is the biggest inhibitor of product success.” They argue that especially in the domain of e-business applications usability is vital to a company’s success, its competitive edge, and perhaps even its survival. In this chapter we will present the conceptual model of the shopping cart and discuss its typical functionalities. Our primary goal is to reach a set of design guidelines that can guarantee user satisfaction and diminish shopping cart abandonment. Moreover, in terms of both the online product catalog, as well as the shopping cart, we explore the potential of incorporating personalization features for improving information presentation and access, speeding up interaction and upgrading the overall user experience in the e-Shop. In the last section of this chapter we conclude the topic of effective catalog and shopping cart design and its crucial effect on enhancing the e-purchase experience and increasing the look-to-buy rates (Lee & Podlaseck, 2000) of an online shop (i.e., the percentage of product impressions, meaning customer accesses to a product page that are eventually converted to purchases).

[1]A metaphor is a possible way to achieve a mapping between the computer system and some reference system known to the users in the real world. A metaphor can provide a unifying design framework and facilitate learning by allowing users to draw upon the knowledge they already have about the reference system (Hudson, 2000).

[2]BizRate.com Web Site. Accessible at http://www.bizrate.com

Effectiveness from User s Standpoint

Knowing the customer has nowadays prevailed as the ultimate business objective. The reason behind this is that by knowing the customer you also know the way to understand and satisfy individual needs. At this point, we should address the topic of user-friendly interaction and usability, as each user cannot be separated from human nature. In our context and by attempting to project to the e-Commerce domain the general factors that assure usability—as defined in the human computer interaction domain (Nielsen, 1993)—an e-Shop should (Markellos et al., 2001):

- Be efficient. The efficiency in the context of e-Commerce means easy and fast product(s) identification and order submission. It is a fact that customers are annoyed with the little struggles that are too frequently part and parcel of doing business online. Their expectations are simple and their choices are infinite. According to Zemke and Connellan (2001), e-Shops should adapt to the ETDBW (Easy-To-Do-Business-With) thinking approach: the point is how we make it simple and effortless for customers to find and use a certain e-Shop, and only then to deal with questions of style and design. ETDBW thinking suggests that all those involved in the e-Shop’s decision making should think first like a customer and last like a technical wizard. Moreover, since an e-purchase completes not at the point of charging the customer’s credit card but at the point when the customer receives the ordered item, efficiency requires delivery to be on time. This means that e-Shops must practice reliability and provide customer support prior to, during and after sales.

- Prevent errors from occurring and provide recovery mechanisms. It is essential to prevent or to eliminate errors occurring when shopping online. In the Web environment, as errors we regard broken links, missing images, missing product details, as well as server failures or long delays due to heavy traffic and any other circumstance that results in a negative customer experience and poor service. We should though also consider as errors all unsuccessful searches that return no results pages. Recovery in this case means that these pages should help customers revise their queries or suggest some kind of solution. There are cases where the e-Shop cannot satisfy a certain product need and this should also be communicated clearly and as soon as possible, so that the customer’s time online is not wasted and is treated with respect.

- Provide subjective satisfaction to the customer. Subjective satisfaction is by definition vague and thus difficult to assure and hard (if not impossible) to measure. A quite comprehensive approach to identifying a set of key features that can guarantee—when implemented well—a positive customer experience is known as the 7Cs (Kearney, 1999) and is introduced and explained in Figure 14-3. Missing from the 7Cs approach is what Vredenburg et al. (2002) reference as “an intuitive and engaging total customer experience,” in their book on UCD. According to them, there was a time when usable meant the absence of obvious user problems. However, in today’s e-Commerce world, the online experience should be such that it accommodates easily what users want to do and provides a design that is pleasant and enjoyable (Jordan, 2000). In other words, usability does not imply boring and visually poor Web environments. On the contrary, it allows engaging experiences but raises the bar even higher by requiring intuitiveness (thus compensating for what may not be totally familiar).

Figure 14-3: 7Cs framework (Kearney, 1999)

In the following two sections we investigate what constitutes an effective catalog and shopping cart for the online shopper and we suggest a set of design guidelines that IT specialists and shop owners should bear in mind while outlining and implementing an e-Shopping environment. Our main objective is to close the gap between what shop owners pursue, what IT people regard as required and what Web users need, enjoy and can actually use easily and fast when shopping online.

[3]eCommerce Trust Study. (n.d.). Cheskin Research/Studio Archetype Sapient. Retrieved from: http://www.sapiend.com/cheskin

Product Catalog Design Guidelines

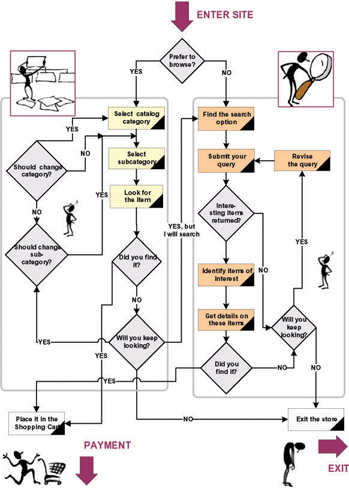

Maes et al. (1999), based on traditional buying behavior research, identify six fundamental stages in the buying process: (1) need identification, (2) product brokering, (3) merchant brokering, (4) negotiation, (5) purchase and delivery, and (6) product service and evaluation. Product catalogs facilitate the first three stages. To better understand the use of catalogs one should take into account the goals and tasks of consumers that mediate the search for a product. The model in Figure 14-4 describes the way an e-Customer interacts with the e-Shop while browsing or searching in order to locate products of interest. This part of online shopping is of great importance, not only because it is an integral portion of actually buying, but also because it determines user impressions and first-level assessment of the e-Shop they have come to contact with. Users consume most of their time during this task and use the feedback from this process to decide whether they will go on with the payment or leave their shopping cart at the cash register and exit. E-Shops suffer from this phenomenon but after all, the Internet is an impersonal, remote and extremely competitive world, which may prove both a blessing and a curse. In order to get the most out of it, customers must be kept satisfied. In the browse/search phase, satisfaction means that the customer should walk through as few states as possible in Figure 14-4 before—hopefully—ending up at the bottommost left state (i.e., proceed to payment). Failure to locate the item(s) means one customer lost and a hard to estimate spreading of disrepute for the e-Shop.

Figure 14-4: e-Customer browse/search model (a revised version of Krug, 2000, p. 56)

An efficient product catalog facilitates easy and fast product identification. The next section discusses the features that when implemented according to each special case requirements, assure catalog efficiency.

Catalog Positioning

According to one of the primary rules of Web design, a Web site’s home page should vividly express the purpose of the site. Specifically for e-Commerce sites, the value of this guideline is enormous. The most straightforward way for an e-Store to indicate its purpose is to place products right on the home page (just as conventional shops place products in their windows). Therefore, guideline number one is that the products catalog should be featured on the home page of the e-Store. More over, it should be either appearing or be one click away from all e-Store pages, thus enabling easy and fast shopping. It is, though, important to point out that apart from the product catalog, links to information about charging, return policy, shipping, credit cards, and delivery should also be available on the home page. The rationale behind this guideline is that in many cases before searching for products to purchase, users may wish to find out whether their credit card is accepted, or that the e-Shop sends products to their country of residence, or that the product can be delivered by a certain date.

Classification Scheme

Constructing an effective catalog classification scheme is not an easy task and it is one of the parts of setting up a successful e-Shop that requires knowing customers well. Product classification should be useful to the customers, helping them locate products without moving forward and back in the hierarchy. Nielsen et al. (2000a) claim that “what constitutes good classification depends on the intended market and how familiar consumers are with the subject matter of the site.” There are cases where classification based on brands makes sense (e.g., in a tennis equipment e-Shop) and cases where it is absolutely senseless (e.g., in a flower e-Shop). Or it may be the case that a classification scheme that is useful for some customers it proves rather cumbersome for others, usually due to issues of internationalization, age, profession, sex, culture or education. A solution to such problems may be the support of multiple classification schemes (with links pointing to each scheme from the home or an upper-level page of the e-Shop) and also where appropriate classification of items in more than one of the hierarchy categories. Both ideas can be easily implemented online and are a good deployment of the trivial hypertext conveniences (i.e., cross reference linking).

The optimum input for deciding on the scheme to apply is the customers themselves. A typical method for acquiring this valuable knowledge is the card short technique (Pearrow, 2000, pp. 63-69). It is one of the simplest yet most useful techniques since it requires little time to complete, and few resources but can offer valuable insight helping designers and e-Shop builders understand how customers (intuitively) expect to find the products organized in categories. After having implemented a classification scheme, usability testing may be applied to indicate further modifications (rearrangements in category listings or additional product references).

In many cases, e-Shops deploy advanced technologies and features for presenting the classification of products (such as Java or Flash) but this can cause problems when a browser does not support such features, or when the connection bandwidth is low and cannot afford long downloading periods.

Before closing the classification topic, it is important to note that prior to deciding on an effective classification scheme, there is a crucial issue to consider: does the e-Shop under consideration really require product classification? The answer to this question depends mainly on the number of available products. When this number is small, it is much more efficient to list products in alphabetic order without any grouping. Direct product listing is quite appropriate especially for products customers like to browse, as they can access a product and see details by clicking on its name and by one click (backwards) return back to the complete product list.

Product Presentation Inside Categories

Once a user has chosen to enter a catalog category, the displayed page contains all products that belong to the specified category. At this point it is crucial for the customer to be able to see what the product looks like. Depending on the kind of the product advanced visualization features and tools may as well be required. For instance, when the product type is running shoes, it is important to provide multiple views from various angles, details about available colors (even the ability to preview the product in the various combinations), and size information. Concerning sizes, e-Shops should provide for internationalization by taking into account for instance that US sizes differ from EU and provide either all size formats or a size conversion mechanism. Information on product availability is also crucial and should be available at a visible spot, since it is a factor that may affect the final buying decision. In general, the type of information appearing for each product listed in a category page depends on the product itself. Designers should keep in mind that customers expect one more level of detail for each product: the product page itself. Thus the product category page(s) are not required to list all product details (nor are they recommended to). They should though contain the kinds of information assumed to be affecting the comparison among products of the same category. After the user has decided upon a product, there is the product page—just one click away—to answer all specific questions and provide a much bigger image.

One of the primary design issues raised when it comes to product category pages is how many items should be listed. Is it better to list all category items at once (resulting in a long and slow page the user has to scroll) or to limit the number of products on each page up to a maximum that usually ranges between five and 20 items (but make the user request successive pages for the complete listing)? Both approaches face the user abandonment threat. In the former case, the single but long page may take too long to download. In the latter, the user may get tired of clicking on successive “next product listing page” links. Thus the guideline can not be very specific.

The final design decision should depend on the kind of merchandise, the amount of information on each product and the estimated downloading times (bearing in mind that users’ delay tolerance is usually around 10 seconds). It is important though to note that users may be a bit more patient if the page starts appearing soon (even if it takes a while longer to complete). In general, a complete category product list should not take more than three page requests and users in the case of product listings expect to scroll down and do so without nuisance. Note also that in order to make sure that the user will scroll down to the bottom of the page and will not miss the last product listed, it is useful to place at the top of each product listing page the total number of products included. By increasing the number of category products listed per page, the e-Shop allows the visual comparison of more products, thus enabling a trivial process for making a buying decision, either online or off-line.

Tools and Functionalities

When an e-Shop sells a wide variety of products (e.g., Web marts), the information load the customer has to handle until locating the product(s) of interest may be “unacceptably” heavy. Thus consumers need additional tools to answer fast and correctly their product enquiries and speed up their decision making process. Such tools comprise filtering tools, comparison tools, search utilities, as well as customer community tools.

- Filtering tools. They are used for narrowing a large item set down to the subset that satisfies a number of additional criteria. Nielsen et al. (2000a) refer to this category of tools as winnowing tools, where winnowing literally means the separation of wheat from chaff (but more generally, the separation of useful from the non-useful). This process is similar to the option “search within search results” offered in some cases along with trivial search and is the further refinement of the returned results set. The set of criteria that can be used by consumers for the filtering is predefined by e-Shop designers and depend on the product distinguishing features, as well as the set of similar products the e-Shop has to offer. Typical criteria comprise price ranges, brands, colors, sizes, and performance characteristics (i.e., speed, capacity and more).

- Comparison tools. Apart from filtering, there are cases of products that are difficult to compare even when the list of all similar products, along with their values for the criteria attributes, is available. Thus the customers’ decision making has to be further assisted using comparison tools. Comparison tools typically offer summarizing tables with similar products on one dimension and features on the other and make it easy to compare them on a feature-by-feature basis. In such settings it is important that the e-Shop allows the customers to specify the products to be compared. In certain cases where each product may have a lot of attributes, it may prove important to allow the customer to also specify the features upon which to base the comparison. There are even cases where the product to be purchased is made up of many separate components, such as a PC, where the comparison may regard alternative configurations (combinations of components). It goes without saying though, that regardless of how useful such decision support tools may prove in the case of large e-Shops, they are a diminishing factor for user satisfaction and efficiency when they are not well-implemented or are available in shops that do not need them (products are either few or not comparable).

- Search. Web users are familiar with the notion of searching and browsing through search results. Thus search is a provision they expect to find available and visible on all pages, so as to resort to it whenever in need. The general guideline is that search should operate the way customers expect it to. It should be tolerant to minor misspellings, allow for synonyms and string keywords, return an easily interpretable results page and link to product pages. The “No results” page should also clearly indicate lack of returned results and where possible provide a way for customers to refine their search until they succeed (provided that the e-Shop has the product(s) of interest available). Search is indeed a big issue and would require a chapter of its own in this book to be covered properly. Relating thought to the online product catalog, search should be regarded as the feature that must be provided in combination with the catalog in order to be a reliable alternative tool to customers for locating the products of interest, compensating for a poorly designed catalog or a customer that cannot “afford” to navigate through the product classification hierarchy (Figure 14-4 illustrates the close connection between catalog browsing and searching). A remarkable finding of Nielsen et al. (2000b) is that if users don’t find what they are looking for on their first search attempt, the odds that they will succeed in their search decrease with each subsequent attempt. This observation imposes a quite demanding requirement for e-Shop designers and builders to “create sophisticated - but simple - search engines capable of delivering the goods on the user’s first search query.”

- Community tools. Information such as customer opinions about a purchased product or product ratings by experts is useful for customers, as it is regarded as less biased (compared to product features as described by their manufacturers or traders). Moreover, ratings and in general recorded opinion of other buyers or experts is a positive sign for e-Shop credibility. If an e-Shop is used by other customers then it has been tested, and if customers return to it and submit their opinion about products, then they are positive about the shop (regardless of their positive or negative opinion about the product). In fact, it is a proof that a customer community has been shaped around the specific shop and this is a plus to its professionalism and trustworthiness and communicates these virtues in an indirect yet clear way. In many e-Shops, such ratings appear on the product pages and not on the product category pages. It is though much wiser, to provide visual rating indications (ticks or stars, for instance) on the product listing in category pages because this way customers can use them as a product comparison factor. Textual comments on the other hand—due to space constraints—should better be placed in the product category pages.

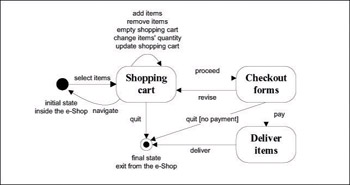

Shopping Cart Guidelines

In a similar way to what happens in traditional supermarkets, online shoppers are given a repository to hold the product(s) to be bought. When items are added to a shopping cart, they are listed on a special purpose page. This page must be easily retrievable at any time before checkout, thus allowing the cart owner to modify the product listing before finalizing and submitting an order. Figure 14-5 presents the state diagram for the shopping cart conceptual model.

Figure 14-5: State diagram for the shopping cart conceptual model (Markellou, 2001)

Shopping cart advantages are significant: quick and easy shopping experience, familiarity, simplicity and clarity in the form of a stepwise process. Many e-Shops use a simplified shopping cart version, known as persistent shopping cart[4], which is visible from every page of the store and provides a quick way to constantly monitor the shopping list status (contents and total cost).

The shopping cart metaphor makes customers intuitively understand the basic functionality (Nielsen, 2000), in the sense that they are familiar with the way it operates. Despite its notable success and wide acceptance, the shopping cart metaphor itself, may cause confusion. The operation of editing the product quantities inside and that of making it zero in order to actually remove a product is not a routine that we are accustomed to use in the real world reference system (i.e., in a supermarket). Not to mention that in the real-life situation paying for the contents of our shopping cart requires emptying the cart from its contents! Despite these problems, the shopping cart is so widely used in online shops that high familiarity diminishes the incidents of such “misuse.”

Following, we provide a set of design guidelines that can dramatically increase shopping cart effectiveness.

Cart Positioning and Representation

The shopping cart should be easy to find. Access, in terms of either viewing its page or adding a specific product in it, should be provided from multiple points e.g., home page, product pages, search page, etc. Experience has proven that a persistent view of the shopping cart on the top right area of all e-Shop pages is very effective, since Web users look first at this area for a link. In addition, a visual indication about whether the shopping cart contains products or not (e.g., by changing icon or color as in Figure 14-2), could be used as a reminder to the customer when browsing product pages or even before heading to other sites, that there is a pending shopping list.

Cart Contents

On entering the cart users expect to see a listing of all products they have selected while browsing the e-Shop’s merchandise. More specifically, for each product it is recommended to include name and code, short description (when the name of the product is either not available or not descriptive enough), quantity (number of items from the product the user wishes to buy), current availability, and price. Special attention should be given to providing a detailed analysis of the order total cost made up of all products in the cart. Additional costs (shipping costs, other charges, and total cost) must be clearly analyzed and justified in order to develop and establish a trustful and reliable relationship between the shopper and the e-Shop. Moreover:

- Navigation buttons and links should be labeled in a way that clearly indicates their effect (i.e., where in the e-Shop the customer will be transferred when following one of them). All interaction controls should state what they do from the user’s point of view. This should be applied when deciding on the exact phrasing of tool-tips, button captions, graphics labels, and hyperlink texts.

- An empty shopping cart should provide shopping instructions (e.g., how to place items in the cart, or how to recalculate the total cost).

- On any error condition, clear and informative error messages should be provided in order to enable users to resolve their problems quickly, thus increasing user satisfaction.

Primary Functionalities

As regards the basic functionalities that should be present in a shopping cart, balance is essential: there should be neither too many options nor too few. The subset of must-have options comprises: add item, remove item, empty shopping cart, change item quantity, recalculate total cost, update shopping cart and proceed to checkout (Bidigare, 2000). In fact, cart updating (an operation that practically recalculates the total cost) could be implemented as an automated process that executes every time the user changes product quantities or shopping cart contents in general. Multiple add and update buttons should be avoided because their excessive use may cause confusion and usability problems. Moreover:

- The names (or codes, in case there are no names available for the products) must be hyperlinks pointing to the corresponding product page with the detailed description, features and probably a photo. This way, users may easily refer to the details of each product. Other useful links include information on the e-Shop return policy, guarantees, privacy policy and security.

- Customers should also be provided with the option to be transferred back to the page they entered the shopping cart from, so shopping can be resumed (usually e-Shops provide a “return to shopping” link for this purpose). This way the customer is prevented from feeling disoriented and may keep on “walking the corridors” of the virtual market place exactly from the point he stopped for a while, in order to take a product off the shelf and put it in the cart (just like in the real-life situation, it is not natural to send the customer to the shop entrance after adding a product to the cart!).

- Last but not least, internationalization issues must be taken into account for currency, shipping costs, credit cards, after sales support, language version of the product manual (where applicable), product sizes (where applicable), etc.

Additional Tools and Options

In addition to the primary operations that should be supported by a shopping cart, there are a number of extra tools and options that can upgrade the overall shopping experience. These include:

- Personal recommendations for related products (and/or highly rated products) that might increase sales. Information from customers past purchases (history) or demographics could be used for producing successful suggestions.

- Option for saving the contents of the shopping cart in a “wish list” or in a shopping list for future reference (some shopping carts support this capability for up to a certain time period, usually 90 days).

- Option for printing the contents of the shopping cart, along with their detailed pricing and total cost.

- Provision of a link to FAQ (frequently asked questions), help or customer support pages. Addressing the questions of customers helps establish trustworthiness.

The list that preceded is probably not exhaustive, and on a case-by-case basis it could be extended or restricted. Our objective though, is to give the reader the widest possible perspective on what customers would like to see available in their shopping cart so as not to be pushed away from the e-Shop, not to have difficulty consulting and updating it and not to feel lost, disoriented, confused or even just not sure about the state of their buying process. The shopping cart should make the user feel in control, at ease and reassured throughout the online transaction.

[4]Dack.com, Best Practices for Designing Shopping Cart and Checkout Interfaces. Available at: http://www.dack.com/web/

The Road Ahead

Foreseen trends for the e-Commerce domain and more specifically for the design of electronic product catalogs and shopping carts, comply with the technological directions adapted for the design of Web applications in general. Nowadays, there is a strong current towards Web usability and UCD and at the same time, more and more e-Shops deliver personalized services in an effort to better address each individual user. The last years, personalization has been implemented in e-Commerce environments in the form of product recommendations, usually placed on product pages (Markellos et al., 2003). This has restricted the real potential of this technology which hasn’t reached the catalog or the shopping cart (with the exception of only a few carts that actually embody product recommendations). The fact is that product catalogs may dramatically benefit from the deployment of personalization techniques (Yen & Kong, 2002), as in essence, what a catalog typically has to address is information overload in large e-Shops and the way to access the information of interest (or product(s) of interest to be more specific). One way to solve this problem is to provide a customized catalog for each customer. However, before any customization can be done, it is first required to collect data about the customers, in order to decide what the customized (or personalized) view of the catalog should be like. Such data regard personal information including demographics and preferences entered explicitly by customers during registration, or in more advanced settings, data on user navigational behavior (Web usage mining) and history of buying behavior recorded and analyzed for the decision making process that will output the personalized shopping experience. Personalization on the Web may take up various forms (Markellou et al., 2005). As regards the use of the catalog, there can be personalized content (in terms of both available categories and products inside categories), personalized structuring (referring to the hierarchy of categories), and personalized presentation (in the sense that product listing pages can be customized according to personal preferences and present for each item only the attributes selected by the specific customer).

Moreover, intelligent agents may be deployed for offering personalized assistance during product browsing, that can even take up the form of an animated (and even talking) character. Such approaches have proven quite successful as people like interacting with a “virtual seller” rather than browsing through successive, passive Web pages. Another fascinating factor that should be considered when discussing Web personalization is the development of the semantic Web and the new potential it is expected to offer to all knowledge discovery and decision making tasks (customer profiling, product and price comparisons, etc.).

The prevalence of Web marketing is another point to consider. Web advertising, personalized marketing, one-to-one customer relationships, special pricing based on buying history, all give e-Shops new and stronger potential to expand the customer base and increase sales, while developing e-loyalty. Marketing on the Web is easy and cost effective, and is expected to grow (even more). Product catalogs and shopping carts may well incorporate advertising both directly (banners, links, photos, special offers, etc.) or indirectly (recommendations, ratings, etc.).

Product catalogs and shopping carts reside at the heart of e-Shops and are the components that concentrate most of the implementation team efforts, and they are the first to be influenced by latest advances in the technological field. A hazard to be avoided is the exaggeration or over optimism in selecting the technological solutions to be used during implementation. It is probably the last guideline of this chapter but it is a crucial one: the technologies to be deployed during product catalog and shopping cart implementation should be restricted to the mature and reliable ones that users are familiar with. If a catalog requires the user to install a special purpose player in order to view its contents, then the e-Shop degrades the user experience in terms of speed, ease and usability. Not mentioning the case where the user fails or refuses to acquire and install the player and abandons the e-Shop. Thus before anything, the designer of an e-Shop must ensure ease of use because “ease of use may be invisible, but its absence certainly isn’t invisible” (Vredenburg et al., 2002, p. 23).

Conclusion

In this chapter we identified the design features that assure the effectiveness of the two most crucial e-Shop components: the product catalog and the shopping cart. We presented a set of guidelines assuring a positive shopping experience, as regarded from the customer’s point of view. If one of the primary business objectives is to create and expand a loyal customer base, it is only natural that the customer will keep coming back at the e-Shop when the prior shopping experience from it is positive. And even though in general “positive” may mean different things to different people, for online shopping the scenery is not that vague because customers are driven by a clearly defined purpose. Based on this and a set of principles that derive from the area of human computer interaction and Web design, we investigated the factors that affect catalog and shopping cart effectiveness and explored ways to satisfy them in practice.

References

Bidigare, S. (2000). Information architecture of the shopping cart. Best Practices for the Information Architectures of E-Commerce Ordering Systems, Argus Associates, Inc. Retrieved from: http://argus-asia.com

Ceri, S., Fraternali, P., & Paraboschi, S. (1999). Design principles for data-intensive Web sites. SIGMOD Record, 28, 84-89.

Hill, A. (2001). Top 5 reasons your customers abandon their shopping carts (and what you can do about it). Ziff Davis Smart Business. Retrieved from: http://www.zdnet.com/ecommerce/stories/main/0,10475,2677306,00.html

Hudson, W. (2000). Metaphor: A double-edged sword. Interactions, 7(3), 11-15.

Jordan, P.W. (2000). Designing pleasurable products: An introduction to the new human factors. Taylor-Francis.

Kearney, A.T. (1999). Creating a high-impact digital customer experience. White Paper. A.T.Kearney, Inc.

Koch, N., & Turk, A. (1997). Towards a methodical development of electronic catalogues. Electronic Markets, 7(3), 28-31.

Kondilis, T., Makris, C., Markellos, K., Markellou, P., & Tsakalidis, A. (2000). Helcom Project. Proceedings of the Second SE European e-Commerce Conference, Sofia, Bulgaria, 121-126.

Krug, S. (2000). Don’t make me think! A common sense approach to Web usability. Circle.com Library, Macmillan USA.

Lee, J., & Podlaseck, M. (2000). Using a starfield visualization for analyzing product performance of online stores. Proceedings of the ACM EC ’00, October 17-20, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Maes, P., Guttman, R.H., & Moukas, A.G. (1999). Agents that buy and sell. Communications of the ACM, 42(3), 81-91.

Markellos, K., Markellou, P., Rigou, M., & Sirmakessis, S. (2001). Modeling the behaviour of e-customers. Proceedings of the PCHCI 2001 Panhellenic Conference with International Participation in Human-Computer Interaction, Patras, Greece, pp. 333-338.

Markellos, K., Markellou, P., Rigou, M., Sirmakessis, S., & Tsakalidis, A. (2003). Designing and developing an effective recommendation system for ecommerce stores. Proceedings of the WEBTEC Euromedia 2003, Plymouth, UK, April 14-16, (pp. 50-54).

Markellou, P. (2001). Designing a usable shopping cart. Proceedings of the Workshop W2 Transforming Web Surfers to E-Shoppers, PCHCI 2001 Panhellenic Conference with International Participation in Human-Computer Interaction, Patras, Greece, 57-61. Retrieved from: http://www.hci.gr/papers.htm

Markellou, P., Rigou, M., & Sirmakessis, S. (2005). Mining for Web personalization. In A. Scime (Ed.), Web mining: Applications and techniques. State University of New York College, Brockport: Idea Group Inc.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability engineering. Morgan Kaufmann.

Nielsen, J. (2000). Designing Web usability: The practice of simplicity. New Riders Publishing.

Nielsen, J., Farrell, S., Snyder, C., & Molich, R. (2000a). E-Commerce user experience: Product pages. Unpublished report, Nielsen Norman Group.

Nielsen, J., Molich, R., Snyder, C., & Farrell, S. (2000b). E-Commerce user experience: Search. Unpublished report, Nielsen Norman Group.

Pearrow, M. (2000). Web site usability handbook. Rockland, MA: Charles River Media, Inc.

Rewick, J. (2000). E-Tailers try to keep shoppers from bolting at checkout point. The Wall Street Journal.

Robn, J. (1998). Creating usable e-commerce sites. StandardView, 6(3).

Segev, A., Wan, D., & Beam, C. (1995). Designing electronic catalogs for business value: Results of the Commercenet Pilot (CMIT Working Paper). Berkeley, CA: Fisher Center for Management and Information Technology University of California.

Smith, E.R. (2000). e-Loyalty: How to keep customers coming back to your Website. HarperBusiness Edition.

Timm, U., & Rosewitz, M. (1998). Electronic sales assistance for product configuration. Proceedings of the 11th International Bled Electronic Commerce Conference – “Electronic Commerce in the Information Society,” Bled, Slovenia, June (Vol. 1, pp. 8-10).

Vredenburg, K., Isensee, S., & Righi, C. (2002). User-centered design: An integrated approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Yen, B.P.-C., & Kong, R.C.W. (2002). Personalization of information access for electronic catalogs on the Web. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications I, Elsevier Science B.V., 20-40.

Zemke, R., & Connellan, T. (2001). E-service: 24 ways to keep your customers – When the competition is just a click away. AMACOM.

Endnotes

1 A metaphor is a possible way to achieve a mapping between the computer system and some reference system known to the users in the real world. A metaphor can provide a unifying design framework and facilitate learning by allowing users to draw upon the knowledge they already have about the reference system (Hudson, 2000).

2 BizRate.com Web Site. Accessible at http://www.bizrate.com

3 eCommerce Trust Study. (n.d.). Cheskin Research/Studio Archetype Sapient. Retrieved from: http://www.sapiend.com/cheskin

4 Dack.com, Best Practices for Designing Shopping Cart and Checkout Interfaces. Available at: http://www.dack.com/web/

Section I - Consumer Behavior in Web-Based Commerce

- Chapter I e-Search: A Conceptual Framework of Online Consumer Behavior

- Chapter II Information Search on the Internet: A Causal Model

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter IV How Consumers Think About Interactive Aspects of Web Advertising

- Chapter V Consumer Complaint Behavior in the Online Environment

Section II - Web Site Usability and Interface Design

- Chapter VI Web Site Quality and Usability in E-Commerce

- Chapter VII Objective and Perceived Complexity and Their Impacts on Internet Communication

- Chapter VIII Personalization Systems and Their Deployment as Web Site Interface Design Decisions

- Chapter IX Extrinsic Plus Intrinsic Human Factors Influencing the Web Usage

Section III - Systems Design for Electronic Commerce

- Chapter X Converting Browsers to Buyers: Key Considerations in Designing Business-to-Consumer Web Sites

- Chapter XI User Satisfaction with Web Portals: An Empirical Study

- Chapter XII Web Design and E-Commerce

- Chapter XIII Shopping Agent Web Sites: A Comparative Shopping Environment

- Chapter XIV Product Catalog and Shopping Cart Effective Design

Section IV - Customer Trust and Loyalty Online

- Chapter XV Customer Trust in Online Commerce

- Chapter XVI Turning Web Surfers into Loyal Customers: Cognitive Lock-In Through Interface Design and Web Site Usability

- Chapter XVII Internet Markets and E-Loyalty

Section V - Social and Legal Influences on Web Marketing and Online Consumers

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 180