Conclusion

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Using Audio As A Game Feedback Device

by Michael Sweet, Creative Director, AudioBrain, Inc.

Sound can have a profound impact on the game. Not only is it important in setting the overall mood for play, it can dictate an emotional responses to the player. Whether you’re struggling to make it to the end of a level or waiting for the next monster to appear from around the corner, the music and sound can make the player’s heart race or stomach drop.

Several years ago I created sound for a little innovative puzzle game called BLiX. You can still run across it on Shockwave.com if you’re interested in playing it. The game brought me several nominations for best audio in a game and the Independent Game Festival Award for Best Audio in 2000.

The object of BLiX is incredibly simple: get the balls into the cup. The game itself was designed to be played by anyone; the interface was iconic, the scoring system didn’t use numbers, there was also no real language in the game design itself.

Below is a basic asset list of the sounds that went into the game.

-

Introductory music

-

Interface rollover sounds

-

Play button sound

-

Timer start sound

-

Timer countdown sound

-

Level music (14 versions which cycle among the 300 levels)

-

In-game musical rollovers

-

Bumper place sound

-

Ball bounce sound

-

Ball into cup sound

-

Finish level sound

-

Interstitial music

-

Timer running low sound

-

Special sounds for level power-ups

-

Game over sound

When designing the sound I wanted the player to create the music through gameplay without actually realizing they were participating in it. All the sound effects are musical phrases that get added to an underlying loop of ambient background techno music. In addition the game space is divided into a grid of nine spaces that have rollovers so as the player moves around the screen placing bumpers and playing the game these musical rollovers trigger simple drum hits and synth notes. In essence the score is self-generated by the user.

At the time, with limited toolsets, we introduced some fairly unique concepts to an Internet puzzle game; the creation of music centered around gameplay. Today there are many newer technologies that allow the composer to really shape narrative in real time through seamless branching of the musical score and dynamic created sound effects. At the time BLiX was done we had to be creative about the use of the limited technology, trying to break the rules of the system.

The sounds themselves were created using software packages Rebirth and Protools. I wanted to integrate lots of delays and effects into the individual sounds. I wanted to also recognize a retro arcade feel to the game, taking beeps and blips to a whole new level. The other developers were all old arcade heads and we wanted to recognize our heritage so to speak.

Adding delays on sounds add a lot of file size to the game. The co-designers of the game let me have full reign over file size, which really allowed me to be creative first instead of being led by the technology or inherent difficulties of the limitations of an Internet game. Although we took out assets to maintain file size once Shockwave.com acquired BLiX, it really allowed me to open up creatively and experiment in ways I really hadn’t before. I was lucky to be working with designers who let me experiment and try new things.

Audio feedback is incredibly important. When I talk to people that play BLiX they always mention the game over sound and how they hate hearing it. I was in the process of taking it out during the creation of the game because I felt it was too harsh, when the other designers (Peter Lee and Eric Zimmerman) told me how much they liked it. Players of BLiX hate getting to the game over sound, and immediately start a new game as a result.

The one sound in the game I didn’t create was the timer running out sound. Peter Lee found this sound and we ended up not changing because it’s another sound that jolts you back to reality. After playing the game for a while you get that sort of numb Tetris-like feeling where the game is a machine and you’re part of it. All of the sudden the timer is running out and it jolts you back to the reality that the game is about to end.

BLiX

It was really important to me that the audio feedback during the game was a single audio-rich experience. The sound effects in BLiX needed to be tightly integrated into the music. Even though we didn’t have the ability to sync sounds to the beats the sounds are so well designed (ultimately to my initial disbelief) and synergistic with the background loops that everyone just considers it music instead of two separate elements.

Something frequently overlooked is that audio feedback can also establish the rhythm of interaction for the player. Digital gameplay has a player interaction that has a specific speed of movement, mouse clicks, and keystrokes. These interactions have rhythm all on their own that the music and SFX can support or detract from.

Similar to film, the game sound designer can use motifs and themes to create metaphors for characters, help transitions, and give direct or indirect feedback to the user about how they’re doing in the game. The power of sound design can also create emotions that are hard to achieve strictly by the visual representation of the game, things like empathy, hatred, love can all be represented through music and sound.

Each game designer should recognize the power that audio has to increase every aspect of his game. Studies have shown that higher quality audio often gives the game player a perceived increase in the overall visual look of the game and heightened awareness during game play.

Author Bio

Michael Sweet is the creative director for Audiobrain. As a composer and sound designer, he has won numerous awards for his work including the prestigious BDA Promax Award 2000 for Best Sound for a Network Package (HBO Zone) and the Best Audio Award at the GDC Independent Games Festival in 2000. Michael’s sound sculptures have traveled around the world, including the Millennium Dome in London, and galleries in New York, Los Angeles, Florence, Berlin, Hong Kong, and Amsterdam.

You can find Michael’s sonic imprints on many award winning games and web sites. Award winning work includes: Sesame Workshop’s MusicWorks, Shockwave’s BLiX & LOOP, RealArcade’s WordUp, and many games for the Cartoon Network. In broadcast, Michael’s work can be heard in many commercials and network identities, including HBO Zone, Comedy Central, CNN, General Motors, Kodak, AT&T/TCI, and The X-Files.

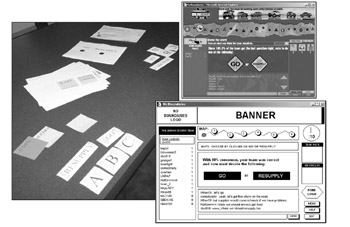

Figure 11.12: From a physical prototype (left), to wireframes (lower right), to final interface (upper right)

Wireframes also act as a tool to facilitate discussions about the game. Reading a design document is fine, but seeing a wireframe takes it to a whole new level. You’d be surprised at how much it helps to have something visual in front of you when you are explaining how your game functions. Once you are done presenting the wireframes to your team, you should have a very good idea of how your interface will look and function, and this knowledge will your artists and programmers get off to a smooth start.

Exercise 11.8: Wireframes

Create a full set of wireframes for your original game prototype. Be sure to include every screen. This will force you to think through all elements of the controls, viewpoint, and interface discussed previously. Once you have completed your wireframes, you will be well-prepared for the specification process that we discuss in Chapter 14.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 162

- Chapter III Two Models of Online Patronage: Why Do Consumers Shop on the Internet?

- Chapter VI Web Site Quality and Usability in E-Commerce

- Chapter VII Objective and Perceived Complexity and Their Impacts on Internet Communication

- Chapter XIV Product Catalog and Shopping Cart Effective Design

- Chapter XVII Internet Markets and E-Loyalty