Displaying Messages Using the MessageBox.Show() Method

A message box is a small dialog box that displays a message to the user. Message boxes are often used to tell the user the result of some action, such as The file has been copied . or The file could not be found . A message box is dismissed when the user clicks one of the message box's available buttons . Most applications have many message boxes, yet developers often don't display messages correctly. It's important to remember that when you display a message to a user, you're communicating with the user. In this section, I want to teach you not only how to use the MessageBox.Show() method to display messages, but how to use the statement effectively.

The MessageBox.Show() method can be used to tell a user something or ask the user a question. In addition to text, which is its primary function, you can also use this function to display an icon or display one or more buttons that the user can click. Although you are free to display whatever text you want, you must choose from a predefined list of icons and buttons.

A MessageBox.Show() method is an overloaded method. This means that the method was written with numerous constructs supporting various options. While coding in Visual Studio .NET, IntelliSense displays a drop-down scrolling list displaying any of the twelve overloaded MessageBox.Show method calls to aid in coding. Following are a few ways to call MessageBox.Show():

To display a message box with specified text, a caption in the title bar, and an OK button, use this syntax:

MessageBox.Show( MessageText, Caption );

To display a message box with specified text, caption, and one or more specific buttons, use this syntax:

MessageBox.Show( MessageText, Caption, Buttons );

To display a message box with specified text, caption, buttons, and icon, use this syntax:

MessageBox.Show( MessageText, Caption, Buttons, Icon ); In all these statements, MessageText is the text to display in the message box, Caption determines what appears in the title bar, Buttons determines which buttons the user sees, and Icon determines what icon (if any) appears in the message box. Consider the following statement, which produces the message box shown in Figure 18.1.

Figure 18.1. A message box in its simplest form.

MessageBox.Show("This is a message."); As you can see, if you omit Buttons , C# displays only an OK button. You should always ensure that the buttons displayed are appropriate for the message.

| The Visual Basic MsgBox() function defaults the caption for the message box to the name of the project. There is no default in C#. |

Specifying Buttons and an Icon

The Buttons parameter contains the "meat" of the message box statement. Using the Buttons parameter, you can display a button (or buttons) in the message box. The Buttons parameter type is MessageBoxButtons, and the allowable values are shown in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1. Allowable Enumerators for MessageBoxButtons

| Members | Description |

|---|---|

| AbortRetryIgnore | Displays Abort, Retry, and Ignore buttons. |

| OK | Displays OK button only. |

| OKCancel | Displays OK and Cancel buttons. |

| YesNoCancel | Displays Yes, No, and Cancel buttons. |

| YesNo | Displays Yes and No buttons. |

| RetryCancel | Displays Retry and Cancel buttons. |

Because the Buttons parameter is an enumerated type, C# gives you an IntelliSense drop-down list when specifying a value for this parameter. Therefore, committing these values to memory isn't all that important; you'll fairly quickly commit the ones you use most often to memory.

The Icon parameter determines the symbol displayed in the message box. The Icon parameter is an enumeration from the MessageBoxIcon type. The MessageBoxIcon has the values shown in Table 18.2.

Table 18.2. Enumerators for MessageBoxIcon

| Members | Description |

|---|---|

| Asterisk | Displays a symbol consisting of a lowercase letter i in a circle. |

| Error | Displays a symbol consisting of a white X in a circle with a red background. |

| Exclamation | Displays a symbol consisting of an exclamation point in a triangle with a yellow background. |

| Hand | Displays a symbol consisting of a white X in a circle with a red background. |

| Information | Displays a symbol consisting of a lowercase letter i in a circle. |

| None | Displays no symbol. |

| Question | Displays a symbol consisting of a question mark in a circle. |

| Stop | Displays a symbol consisting of a white X in a circle with a red background. |

| Warning | Displays a symbol consisting of an exclamation point in a triangle with a yellow background. |

The Icon parameter is also an enumerated type; therefore, C# gives you an IntelliSense drop-down list when specifying a value for this parameter.

The message box in Figure 18.2 was created with the following statement:

MessageBox.Show("I'm about to do something...","MessageBox sample", MessageBoxButtons.OKCancel,MessageBoxIcon.Information); Figure 18.2. Assign the Information icon to general messages.

The message box in Figure 18.3 was created with a statement almost identical to the previous one, except that the second button is designated the default button. If a user presses the Enter key with a message box displayed, the message box acts as though the user clicked the default button. You'll want to give careful consideration to the default button in each message box. For example, if the application is about to do something that the user probably doesn't want to do, it's best to make the Cancel button the default button ”in case the user is a bit quick when pressing the Enter key. Following is the statement used to generate the message box in Figure 18.3.

Figure 18.3. The default button has a dark border.

MessageBox.Show("I'm about to do something...","MessageBox sample", MessageBoxButtons.OKCancel,MessageBoxIcon.Information, MessageBoxDefaultButton.Button2); In Figure 18.4, the Error icon is shown. The Error icon is best used in rare circumstances, such as when an exception has occurred. Overusing the Error icon is like crying wolf ”when a real problem emerges, the user might not take notice. Notice here how I've displayed only the OK button. If something has already happened and there's nothing the user can do about it, don't bother giving the user a Cancel button. The following statement generated the message box shown in Figure 18.4.

Figure 18.4. If users have no control over what has occurred, don't give them a Cancel button.

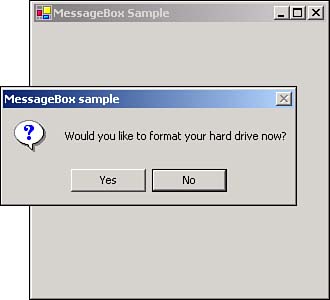

MessageBox.Show("Something bad has happened!","MessageBox sample", MessageBoxButtons.OK,MessageBoxIcon.Error); In Figure 18.5, a question has been posed to the user, so I chose to display the Question icon. Also note how I assumed that the user would probably choose No, so I made the second button the default. In the next section, you'll learn how to determine which button the user clicks. Here's the statement used to generate the message box shown in Figure 18.5:

MessageBox.Show("Would you like to format your hard drive now?", "MessageBox sample",MessageBoxButtons.YesNo,MessageBoxIcon.Question, MessageBoxDefaultButton.Button2); Figure 18.5. Message boxes can be used to ask a question.

As you can see, designating buttons and icons is not all that difficult. The real thought comes in determining which buttons and icons are appropriate for a given situation.

Determining Which Button Is Clicked

You'll probably find that many of your message boxes are simple, containing only an OK button. For other message boxes, however, you'll need to determine which button a user clicks. Why give the user a choice if you're not going to act on that choice? The MessageBox.Show() method returns the button clicked as a DialogResult enumeration. The DialogResult has the following values, as shown in Table 18.3.

Table 18.3. Enumerators for DialogResult

| Members | Description |

|---|---|

| Abort | Return value Abort, usually sent from a button labeled Abort. |

| Cancel | Return value Cancel, usually sent from a button labeled Cancel. |

| Ignore | Return value Ignore, usually sent from a button labeled Ignore. |

| No | Return value No, usually sent from a button labeled No. |

| None | Nothing is returned from the dialog box. The model dialog will continue running. |

| OK | Return value OK, usually sent from a button labeled OK. |

| Retry | Return value Retry, usually sent from a button labeled Retry. |

| Yes | Return value Yes, usually sent from a button labeled Yes. |

Performing actions based on the button clicked is a matter of using one of the decision constructs. For example:

if (MessageBox.Show("Would you like to do X?","MessageBox sample", MessageBoxButtons.YesNo,MessageBoxIcon.Question) == DialogResult.Yes) // Code to do X would go here. As you can see, MessageBox.Show() is a method that gives you a lot of "bang for your buck"; it offers considerable flexibility.

Crafting Good Messages

The MessageBox.Show() method is surprisingly simple to use, considering all the different forms of messages it enables you to create. The real trick is in providing appropriate messages to users and appropriate times. In addition to considering the icon and buttons to display in a message, you should follow these guidelines for crafting message text.

-

Use a formal tone. Don't use large words, and avoid using contractions. Strive to make the text immediately understandable and not overly fancy; a message box is not a place to show off your literary skills.

-

Limit messages to two or three lines. Lengthy messages are not only harder for users to read, but they can also be intimidating. When a message box is used to ask a question, make the question as simple as possible.

-

Never make users feel as though they've done something wrong. Users will, and do, make mistakes, but you should craft messages that take the sting out of the situation.

-

Spell check all message text. Visual Studio's code editor doesn't spell check for you, so you should type your messages into a program such as Word and spell check the text before pasting it into your code. Spelling errors have an adverse effect on a user's perception of a program.

-

Avoid technical jargon. Just because someone uses software doesn't mean that he or she is a technical person; explain things in plain English.

| Top |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 253