Background: Reasons for Network Formation

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

The reasons given in the literature for the formation of strategic networks can be grouped into two types: value creation and cost savings (Tsang, 2000). However, these two reasons are controversial. On the one hand, much of the literature focuses exclusively on the potential of inter-organizational relations for generating value (see Varadarajan & Cunningham, 1995; Hamel, 1991; Eisenhardt, 1996). On the other hand, some authors see strategic networks as a means of saving on various costs (see Jarillo, 1988, 1993; Williamson, 1991; Clemons & Row, 1992; Gerybadze, 1995). Nevertheless, both views are incomplete when taken separately (Tsang, 2000). We shall now review the value-creation and cost-savings explanations for network formation. Both views will then be combined into an eclectic model.

Value Creation

Firms participating in strategic networks can create value in various ways. Among the advantages that the literature ascribes to networks are that they provide faster market penetration, the sharing of financial risks (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000), encouragement of innovation, access to knowledge valuable for competing (Hitt et al., 2000), and the reputation required in the market (Sharman, Gray, & Yin, 1991). In short, they make it easier for firms to gain access to the resources and capabilities that they need but do not possess, and for them to learn new capabilities (Kogut, 1988; Ireland et al., 2001).

From the perspective of the resource-based view, firms form strategic networks in order to gain value, an aim that can be broken down into three general objectives: obtaining, exploiting, and developing resources and capabilities.

Obtaining resources and capabilities can be directed at (1) gaining know-how (Powell, 1987; Kogut, 1988; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000); (2) looking for complementary resources and capabilities from other network members (Poppo & Zenger, 1995; Dyer & Singh, 1998; Harrison et al., 2001), which may not be in the market (Oliver, 1997); (3) creating specialized resources and capabilities in combination with those from another firm (Klein, Crawford, & Alchian, 1978; Teece, 1987) to generate Ricardian rents (Rumelt, 1987); or (4) externalizing resources and capabilities (Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000) that the firm wants to get rid of in order to concentrate on its core ones (Prahalad, & Hamel, 1990; McGee, 1999).

As far as the exploitation of resources and capabilities is concerned, firms may have the aim of (1) using resources and capabilities in the network that were until then dormant (Baden-Fuller & Volberda, 1996, 1997; Baden-Fuller & Stopford, 1994; Garud & Nayyar, 1994); or (2) making better use of their core resources and capabilities (Arndt, 1979; Tsang, 2000) in other markets or other industries (Varadarajan & Cunningham, 1995; Kumar & van Dissel, 1996; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000).

Finally, the development of new resources and capabilities may lead to the use in the network of unused resources and capabilities to keep them “alive,” thereby providing an option for generating dynamic capabilities when the environment changes (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Fiol, 2001).

The firm Fourth Shift Corp. is an example of how a firm tries to obtain from other firms resources and capabilities complementary to its own. It combines them to produce specialized resources and capabilities, which are consequently difficult to imitate and which are more easily exploited in new markets. Fourth Shift Corp. (based in Minneapolis) supplies applications in ERP (enterprise resource planning), CRM (customer relationship management), and financial management. This firm formed an alliance in 2000 with the consultants Grant Thornton. Both firms had the aim thereby of increasing their portfolio of clients. Thus, Grant Thornton focused on providing e-business consulting, while Fourth Shift centered on implementing e-business software (previously recommended by its alliance partner to clients requesting e-business consultancy).

Another interesting alliance was formed by the bank Chase Manhattan with ShopNow.com, through its Internet banking project Chase.com. ShopNow.com had experience in electronic shopping centers. The result was ChaseShop.com, an electronic shopping center earning revenues in three areas: by customers using credit cards from Chase; by selling advertising space on their Web page; and by charging for developing and hosting clients’ online stores. Again, here we can see that firms have sought to create value by accessing the complementary resources and capabilities made available in an inter-organizational relation.

Cost Savings

With regard to costs, opting for forming a network rather than conducting transactions in the market would depend on the ability of certain firms within the network structure to reduce transaction costs in the market (Clemons & Row, 1992; Kumar & van Dissel, 1996; Tsang, 2000), without incurring excessive transaction costs in the network or additional production costs. Moreover, for the network to make sense, its transaction and production costs must not be higher than those incurred in an integrated firm (hierarchical situation) (Jarillo, 1993).

Jarillo (1993) provided a model of what the economic conditions should be for it to be reasonable to construct a strategic network. The model includes the internal costs of implementing an activity (IC), the price charged by an external supplier for carrying out that activity (EP), and the market transaction costs (TCM). Thus, the necessary but not sufficient condition for forming a network is that EP < IC. But this would lead a firm to opt for the market structure, too. The sufficient condition would be that, in addition to the above, TCM would satisfy TCM + EP > IC, with which the firm would opt for vertical integration, unless it was able to reduce network transaction costs (TCN) to the point of satisfying TCN + EP < IC. According to Gerybadze (1995), there are three ways of reducing external costs (TCM + EP) with respect to the internal costs (IC) within the network form of organization. First, the transaction costs can be reduced by transacting with only a reduced number of market members who are well-known and trusted, thanks to the specialization of the interchanges that occur and the building of fluent channels of communication. Second, a successful network leads to the efficient reduction of production costs by benefiting from specialization and scale. Third, a discipline of cost control is introduced that may not occur in an integrated organization with captive internal markets (Jarillo, 1988).

It is particularly important to clearly define what transaction costs affect strategic networks. Williamson (1989) divided transaction costs into information costs, negotiation costs, and guarantee (or safeguard) costs. However, these costs refer to transactions carried out in the market, which are only temporary, and which are unlikely to be repeated. This makes his taxonomy inappropriate for stable network relations. In a strategic network of firms, it is not necessary to look for information or to negotiate continually, and there are safeguards inherent in the operation of the network (because stable relationships permit the parties to penalize previous opportunistic behaviors).

In this sense, it would seem to be preferable to adopt the taxonomy used by Clemons and Row (1992), for whom the transaction costs of firms operating in networks are broken down into coordination costs and transaction risks. The latter refers to the possibility that network members may behave opportunistically and against the spirit of the contract.

Finally, with respect to production costs, the literature points out that the formation of strategic networks leads to economies of scale (Arndt, 1979) and scope that would be impossible to achieve internally in an hierarchical firm (Clemons & Row, 1992; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000). Moreover, strategic networks allow better coordination with suppliers (Konsynski, 1993; Van der Heijden et al., 1995), which leads to improvements in terms of production costs, stock, production times, delivery times, etc.

The Benetton network (dedicated to producing and distributing colorful knitwear) is a clear example of how a firm creates a network when the production costs of other companies are lower than its own internal costs, and how the firm takes advantage of the situation cutting its market transaction costs. This network- based model revolves around granting franchises with the exclusive right to distribute products, strictly controlled by Benetton (the brand owner). There is a dispersed production system involving more than 200 “independent” subcontractors. In this way, Benetton obtains a very flexible production system, being able to react rapidly to unpredictable market situations and changes in customer preferences.

Benetton’s information system plays an important role in the response of the company to market variations detected in its franchised stores. These shops communicate directly with the head office in Ponzano (Italy). The firm’s ability to adjust its production levels rapidly to changing sales is made easier by the fact that it produces its garments with colorless wool, and only subsequently dyes them in accordance with customer tastes.

Organizing activities through a network has led to important cuts in production costs, due to the highly specialized and flexible subcontractors and the direct control the managers of each subcontractor exercise over their parts of the activity of the network.

Moreover, the fact that the relationship between the firms in the network is permanent eliminates the typical transaction costs that firms incur when engaging in one-off or unstable relationships. In this sense, there are practically zero search costs for finding new suppliers; and there are no contracting or negotiation costs. Although stable relations only require contracts to be signed the first time, Benetton goes further. The degree of confidence it inspires is such that the firms in the network do not sign formal contracts at all. This fact would theoretically increase perceptions that the central firm in the network can engage in opportunistic behavior, thereby increasing perceived transaction risks. However, such an increase in the transaction costs does not occur, because of various practices of Benetton and the nonopportunistic reputation it has gained. This prevents transaction risks from rising, so obviating the need to incur guarantee (or safeguard) costs.

With regard to the above-mentioned practices that reduce the perceived transaction risks, we might mention that the firm finances specialized investments in the network subcontractors, either totally or partially. The companies dependent on Benetton (the central firm) are thereby not obliged to invest important sums on specific assets that can only be used within the network; Benetton’s investment will convince firms that they are unlikely to be exploited by the central firm. Moreover, the central firm will find it less likely that its subcontractors engage in opportunistic behavior, as they invest to a greater or lesser extent in resources and capabilities that are complementary (and normally also specific) to the investment made by Benetton. These investments not only involve physical assets, but also knowledge, know-how, and the development of organizational routines.

An Eclectic Model

Transaction cost economics is complemented by the resource-based view. From the resource-based perspective, resources and capabilities on which the firm depends for its current or future competitive advantages are never externalized for strategic reasons, even if this were recommendable from the perspective of transaction cost economics because of costs. In fact, occasionally, alliances are formed that involve increased transaction and production costs in the short term, in the expectance of adding value in the medium to long term. Moreover, it is also frequent for strategic networks to be formed in which there is no added value, as far as cost reductions are concerned. In this sense, the complementary orientations toward value and costs of each one of these theories (Conner, 1991; Zajac & Olsen, 1993; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997) make it evident that an eclectic perspective is required that integrates both theoretical approaches.

Thus, it is not logical to analyze cost reasons and value reasons separately, because the formation of the network may be due to the combined effects of both factors. For example, cost reasons may cancel out value reasons if the value achieved by the network does not compensate the costs incurred; or equally, the cost savings may be less than the added value provided by the other forms of governance (hierarchy or market). The network would not be formed even though it adds value in the first case and reduces costs in the second.

Hence, in order to justify the formation of a strategic network, the combined effect of cost and value reasons must be analyzed in relation to the market option as well as to the option of vertical integration.

Jointly taking into account the conditions of value and cost, we can say that opting for joining a network is advisable, compared to acting freely in the market, when:

(VN – VM + TCM) > (TCN + PCN-M)

where:

VN = value obtained when the firm works in the network

VM = value obtained when the firm undertakes transactions in the market

TCM = transaction cost incurred when organizing the activity in the market

TCN = transaction cost incurred when organizing the activity through the network

PCN-M = difference in production costs between the network case and the market case

The network will be formed and maintained if the net value obtained from it, and the transaction costs saved by not operating in the market, are not outweighed by the additional transaction and production costs generated by the network.

Moreover, it will be better for a firm to join the network than to be integrated in an hierarchy (a firm) when the following expression holds:

(VN – VH) > (TCN + PCN-H)

where:

VN = value obtained when the firm works in the network

VH = value obtained when the firm works in a hierarchy (as an integrated firm)

TCN = transaction cost incurred when the activity is organized through the network

PCN-H = difference in production costs between the network case and the hierarchy case

In short, the reasons for forming a network rather than opting for hierarchical governance are that the added value provided by the network is greater than the transaction costs plus the increase in production costs within the network. In reality, the production costs in a network tend to be lower than in an integrated firm, and thus, there are normally reductions in production costs in the network rather than increases.

It can be seen that the transaction costs within the hierarchical form (TCH) are not considered in the last equation. Although Demsetz (1988) argued that transaction costs are not removed by producing within an integrated firm, due to the firm having to buy inputs from other firms, here we do not consider any TCH, not because they do not occur, but because they are much lower than the other transaction costs (Tsang, 2000). It is fair to point out that there are occasions in which transaction costs within an hierarchy are greater than the external transaction costs (Eccles & White, 1988). However, this is not common.

The Role of IT in Network Formation

According to the equations proposed above, and from the value perspective, it should be assessed if IT favors the formation of networks, because it can add value to the networks or reduce the value of the hierarchical or market forms. But it seems unlikely that IT could reduce value in hierarchical and market systems of governance. In fact, the reverse is much more likely (for example in the electronic markets based on the Internet that have created new business opportunities in the market system). Thus, our analysis should focus on the role of IT in creating or adding value in networks. Specifically, we will look at the complementary role of IT in networks. This complementarity can be understood as the ability of IT to leverage the value generated by the networks, supporting their operations and helping firms to achieve the objectives that were behind the formation of the network in the first place. This complementarity fits the definitions of Teece (1986), Amit and Shoemaker (1993), and Milgrom and Roberts (1995).

As far as the “transaction cost” variables (TCM, TCN) are concerned, we shall study how IT can reduce the transaction costs of the network structure, in view of the fact that increasing the transaction costs in the whole market is not very probable. This increase can occur in exceptional cases in which market intermediation is monopolized and the firms of the market bear high transaction costs due to the abusive use of this monopoly[1], and the high cost of changing suppliers. Although these practices are possible, they are normally only temporary, either because of antimonopoly legal action or because firms try to avoid falling captive (Mata, Fuerst, & Barney, 1995) or because of the search for network externalities (Shapiro & Varian, 1999).

In order to study the role of IT in reducing transaction costs of networks, we shall analyze the role of IT in reducing coordination costs and transaction risks (Clemons & Row, 1992), the aforementioned components of transaction costs in stable inter-organizational relations.

Thus, breaking down the transaction costs of the network into coordination costs and transaction risk (TC = CC + TR) in the two expressions above that justified the formation of the network as opposed to the hierarchy or market form, the following expressions are obtained:

(VN – VM + TCM) > (CCN + TRN + PCN-M) (VN – VH) > (CCN + TRN + PCN-H)

The literature recognizes that IOISs can reduce coordination costs (Child, 1987; Malone, Yates, & Benjamin, 1987; Rockart & Short, 1989), such that information relations can reduce the costs of control and coordination in the network. This allows firms to subcontract without losing efficient control over the operation of the contractual relation (Sanchez, 2001). There has been less said about transaction risks, although some authors have ascribed to IT an influence on these through its effect on information asymmetries, transaction-specific capital investment, and loss of control over information resources made available on the network (Clemons & Row, 1992).

IT can also reduce “production costs” (PCN-M, PCN-H), through the use, for example, of design tools and computer-aided production or engineering (Arjonilla & Medina, 2002). In principle, the reduction in production costs would affect networked structures as much as the other structures. There are occasions, however, where savings in production costs are due to the network, because the firms can concentrate on their core resources and capabilities and join forces with the best firms for externalized activities (McGee, 1999).

The “value” variable may include the benefits accruing from becoming associated with firms with reduced production costs or by lower production costs due to network synergies. In view of the obvious difficulty of untangling the value created in a network from the reductions in the production costs of the network (Demsetz, 1988), we opted not to analyze the production costs independently, and to take these improvements as value added by the network. From this perspective, IT plays a complementary role here too in generating this value.

In the following section, we propose some propositions relating to the question of whether IT can favor the formation and maintenance of networks by adding value, reducing coordination costs, or reducing transaction risks. If this is the case, IT favors the option of working in a network against that of operating in the market or hierarchy system, as shown in the following expressions:

( VN – VM + TCM) > ( CCN + TRN + PCN-M)

( VN – VH) > ( CCN + TRN + PCN-H)

Propositions

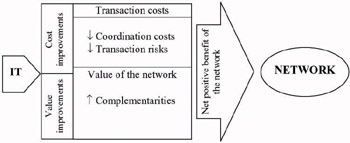

In coherence with the above reasoning, we propose various propositions on IT’s role as an engine for the formation of strategic networks. These propositions will be based on the relations displayed in Figure 1. In this model, IT is seen as improving transaction costs by reducing both coordination costs and transaction risks. Moreover, IT plays a complementary role that allows it to leverage the value created by the strategic network. As we have seen, we consider that the reduction in production costs in networks is equivalent to greater added value.

Figure 1: A preliminary theoretical model

Whatever the combination of cost and value reasons, the network is a better system of governance than the market or hierarchy systems, if the net benefit with respect to these systems, produced by the variations in value and transaction costs, is positive.

Complementarity

The complementary role of IT is expressed in Proposition 1.

Proposition 1 - IT complements in a contingent way the management of firms that operate within a network.

This first proposition can be broken down into several secondary propositions describing the function of IT in networks in more detail. These propositions analyze the ability of IT, acting as a complementary resource, to increase the value created by the network. This is expressed in Propositions 1.1 and 1.2. Other propositions derived from Proposition 1 show that the support role of IT may be contingent on various circumstances, which leads to four contingent propositions (from 1.3 to 1.6), focusing on the role of the type, geographic distance, physical or information character of the activities, and the compatibility of the IT systems of the distinct members of the network. Our interest in studying this contingent effect lies in that it impacts on the role that IT plays as “lever” of the value generated by the network.

In Proposition 1.1, we extrapolate from the individual firm to the strategic network the support that IT lends to the following functions: the planning (Davis & Olson, 1989; Monforte, 1995; Arjonilla & Medina, 2002), implementation (Porter & Millar, 1986; Arjonilla & Medina, 2002), and control of activities (Davis & Olson, 1989). As Grandori and Soda (1995) pointed out, the processes of planning and control in the individual firm are not very different from those required in strategic networks.

Proposition 1.1 - IT complements the management (planning, implementation, and control) of the activities of firms that operate in networks.

Networks play an important role in the processes of learning and interchange of knowledge between different firms (Kogut, 1988; Hitt et al., 2000; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000). Communication and connectivity support collective behavior, foster the creation of a common knowledge base, and accelerate learning curves (Winch et al., 1997), as well as improve the absorptive capacity (Medina & Ruiz, 1999). IT applications in this area can be used to store knowledge, improve knowledge communication, and identify and contact people with specific knowledge. Therefore, Proposition 1.2 can be expressed in the following synthesized form:

Proposition 1.2 - IT favors the creation of a common knowledge base in networks, and accelerates learning curves.

It is widely recognized in the literature that there are differences in the IT used depending on the organizational activities that it supports (Monforte, 1995; Gil- Pechuan, 1996; Arjonilla & Medina, 2002). Similarly, Porter and Millar (1986) stressed the use of different information technologies for the different activities in the value chain. Proposition 1.3 suggests that the types of activities shared in the network also influence the type and complementarity of IT used.

Proposition 1.3 - The complementarity and type of IT used in strategic networks depend on the types of activities shared.

The geographical distance of the activities in a network makes the coordination of the firms that form it difficult. Under these circumstances, it would be reasonable to expect that the use of IT would be more intensive, because it improves (or makes possible) coordination, control, communication, and working in groups, in spite of distances. In view of this, we put forward Proposition 1.4, which also assesses the possibility that the type of IT used differs according to the distance:

Proposition 1.4 - The intensity and type of IT used in a network depend on the geographical distance separating the firms.

For Porter and Millar (1986), the physical component of activities comprises the physical tasks carried out, and the information component comprises the capture, processing, and transmission of the information required for the activities to be carried out. These authors stress how, in the past, technology had improved only in its support of the physical component. However, they argued that the situation has now changed, in that it is the information component of activities that is now enjoying exponential improvements thanks to the new technologies. This can also be seen in Edwards, Ward, and Bytheway (1997), in their study of the source of benefits accruing from the application of IT to the external value chain. In this sense, we propose Proposition 1.5 that suggests that the intensity and type of the IT used in network activities depend on the physical and information components of these activities.

Proposition 1.5 - The intensity and type of IT used in a strategic network depend on the physical and information components of network activities.

Finally, Proposition 1.6 expresses the importance of the coherence between the information systems of the firms in the network. According to Dyer and Singh (1998), in order for a firm to achieve complementarities with other members of the network, it is necessary for it to develop a certain organizational complementarity. It needs to make sure that the ITs used in the different firms that make up the network are compatible, because IT is fundamental in the systems of control and information.

Proposition 1.6 - Compatibility between the IT systems of the firms in networks improves the benefits of the relation.

Coordination costs

As we saw above, these costs form part of the transaction costs that firms incur when transacting with others (Williamson, 1975, 1985; Clemons & Row, 1992), and the literature recognizes the ability of IOISs to reduce them (Child, 1987; Malone, Yates, & Benjamin, 1987; Rockart & Short, 1989). In this sense, we put forward the following generic proposition:

Proposition 2 - IT reduces coordination costs in strategic networks.

Extending to networks the structural elements of coordination sufficiently well- known in individual organizations (see Mintzberg, 1979; Galbraith, 1973), we can see that coordination of the networks can be based on the following mechanisms: (1) the mutual adaptation between the different members of the network, in which lateral relations play an important role (Winch et al., 1997); (2) the planning and control that standardizes the results obtained; and (3) inter- organizational routines.

IT plays an important role in the application of these mechanisms. Thus, the literature recognizes the function of IT in reducing coordination costs, because it improves coordination, control, communication, and working in groups (Rockart & Short, 1989; Clemons & Row, 1992; Kumar & van Dissel, 1996), allowing for faster communication in decision making involving liaison staff and in overcoming problems of distance or time. IT has also been shown to support planning (Davis & Olson, 1989; Monforte, 1995), facilitating the gathering of internal and external information for complex calculations, simulations, and models (Arjonilla & Medina, 2002). Moreover, IT also helps in the communication of the agreed plan to the agents affected. With regard to its support role in control, IT is used for producing normal and ad hoc reports (Davis & Olson, 1989); for combining or breaking down variables of interest, in spite of the distance between points being controlled; for calculating more complex control indicators; and for quickly finding deviations and their causes (Arjonilla & Medina, 2002). In this way, there is more efficient detection and solution of problems. Moreover, occasionally the need for explicit control is relaxed due to organizational routines (Nelson & Winter, 1982), or in this case, inter-organizational routines. The critical resources of firms can cross over company limits and become incorporated into inter- organizational routines and processes (Dyer & Singh, 1998). IT can also become incorporated into these routines and can, in fact, improve them. This reasoning leads us to break down Proposition 2 into the following secondary propositions:

Proposition 2.1 - IT reduces coordination costs by fostering mutual adaptation and lateral relations between firms coordinating their activities in the network.

Proposition 2.2 - IT reduces coordination costs in networks by improving the planning of shared or related activities.

Proposition 2.3 - IT reduces coordination costs in networks by improving the control of shared or related activities.

Proposition 2.4 - IT reduces coordination costs by supporting inter- organizational routines.

It can be seen that Propositions 2.2 and 2.3 are similar to Proposition 1.1, relative to IT complementarity. This is, in fact, no accident. Many of the functions carried out using IT have a dual effect in improving value in the network and reducing coordination costs. As we saw above, it is difficult to separate the variables of cost and value (Demsetz, 1988).

Transaction Risks

Even if IT reduces coordination costs between firms, this does not immediately lead firms to opt for the network form of governance if this would lead to an increase in the probability of opportunistic behavior, where members of the network are exploited within the relation. As is expressed in Proposition 3, the question of whether IT reduces transaction risks (or at least does not increase them) must be addressed:

Proposition 3 - IT reduces transaction risks in strategic networks.

Authors have identified three possible sources of risk in transactions: (1) transaction-specific capital investment that has little value outside the relation (Williamson, 1975; Klein, Crawford, & Alchian, 1978; Milgrom & Roberts, 1993); (2) information asymmetries that prevent the control of the behavior of the network members (Clemons & Row, 1992); and (3) the loss of control over resources placed at the disposal of the relation, fundamentally information, which is used by firms in competition with the original owner (Williamson, 1991; Loebecke, Fenema, & Powell, 1999; Tsang, 2000). Thus, testing this proposition requires us to analyze the impact of IT on transaction-specific capital investment, on information asymmetries, and on the possibility of losing control over shared resources.

Regarding transaction-specific capital investments, it is significant that firms are increasingly tending to use standard IT for coordination between firms (Zenger & Hesterly, 1997), technologies that are still useful if a member wishes to leave the network, and that allow firms to benefit from the externalities they provide. Porter (1990) confirmed that every specialized resource loses specialization in time. The more the standard technologies develop, the less investment in transaction-specific IT will be made, and the easier it will be to establish new relations with suppliers and customers (Sanchez, 2001). Thus, as is reflected in Proposition 3.1, standard IT discourages opportunistic behavior. Complementary to this proposition, Proposition 3.2 suggests that some firms may avoid belonging to networks that require them to invest in transaction-specific IT, due to the fact that this investment increases transaction costs (Cainarca, Columbo, & Mariotti, 1993; Zenger & Hesterly, 1997).

Proposition 3.1 - Standard IT reduces the transaction risks in networks caused by transaction-specific capital investment, and so encourages network formation.

Proposition 3.2 - Costly and transaction-specific capital investment in IT hinders participation in networks by increasing transaction risks.

With regard to the second source of transaction risk, IT can expose member behavior, reducing information asymmetries and thereby reducing opportunistic behavior. All this will lead to a reduction in transaction risks (Rockart & Short, 1989; Kumar & van Dissel, 1996). As is reflected in Proposition 3.3, this information transparency allows firms to control the behavior of the other members, which will lead to increasing confidence that no firm will attempt to exploit the others in the network, and that the benefits of operating in the network will be shared equitably. The relation will thereby have more chance of being long lasting.

Proposition 3.3 - IT reduces the transaction risks in networks deriving from information asymmetries.

Nevertheless, IT may increase transaction risks by making it easier for firms to lose control of resources placed at the disposal of the network, fundamentally those resources based on information and know-how (Clemons & Row, 1992). The problem of loss of control over resources, when, for example, one of the network members attempts to learn more from another than was initially agreed (Tsang, 2000), is exacerbated by easy access to information stored electronically. It is a problem that can be ameliorated, in part, by greater control of, or, what amounts to the same thing, by reducing information asymmetries (see Proposition 3.3). In this sense, it is necessary to express this in a proposition:

Proposition 3.4 - IT increases the transaction risk that derives from the possibility of firms losing control of resources.

As we have seen, IT may have a dual effect in terms of transaction risks, because it can both reduce these risks (Propositions 3.1 and 3.3) and increase them (Propositions 3.2 and 3.4). This paradox requires a more detailed analysis, which we shall develop in the following sections.

[1]A well-known case is that of American Airlines, which increased the transaction costs of the airlines that posed a threat to it, increasing their costs or hindering their use of its widely used computer system for reservations, the program SABRE, which connects an airline’s electronic ticket sales with travel agencies.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 148