Competency-Based Employee Development

Overview

It is difficult to discuss employee development as a formal HR initiative because applications labeled "employee development" have been so diverse. As an HR function, employee development has been somewhat of a catchall for many initiatives intended to improve employee and organizational performance. However, there is little agreement among HR professionals or organization leaders on what constitutes employee development.

Employee development, career development, career management, career planning, career guidance, career coaching, career counseling, mentoring, and initiatives with similar names and labels have been used by organizations. However, these initiatives have often lacked formal definition and specific objectives, and consequently it has been difficult to ascertain what benefits to the organization they have yielded. While some organizations have well-established and -defined employee development initiatives that are linked with business and HR strategies and are aligned with employees' life-career goals, other organizations sometimes turn to initiatives of this type in an attempt to resolve a crisis. Examples include the following situations:

- An organization is downsizing or planning layoffs and decides to provide outplacement services for its employees.

- New business outside an organization's area of core competence creates a demand for current employees to have new or different competencies.

- An organization wants to demonstrate its commitment to achieving diversity or equal employment opportunity goals.

- A merger changes or adds work roles and procedures.

- An organization wants a visible employee development function that will attract or retain exemplary performers.

- A high percentage of an organization's exemplary performers are leaving to work elsewhere.

- An organization is losing key employees due to retirement, resulting in a loss of organization knowledge.

One of the difficulties in discussing, planning, implementing, and maintaining an employee development initiative is that people have different ideas about the nature of employee development, its priority within the organization, and its goals, design, implementation, and application relative to other HR development systems. For example, competency acquisition training is sometimes offered to employees as a "career development" opportunity when, in fact, the main objective of the training is to make them competent (or more competent) in performing their current work. Since becoming more competent is a foundation outcome for employee development as we view it, the opportunity might be considered not only training but also development in that the competencies acquired could have long-term significance for employees' future marketability or life-career satisfaction. Yet the ambiguous definitions could confuse these employees, who might expect some wonderful "career opportunity" (often translated as "promotion") to follow their "employee development" experience. This could possibly damage employee morale and compromise the success of a well-defined and well-managed competency-based employee development system.

Adding to the confusion, career development, which is often mentioned in tandem with employee development, has meaning relative to the context in which it is used. Traditionally, career development meant upward mobility, an eventual, perhaps inevitable, promotion to a work role with greater responsibilities and increased compensation. Today, upward mobility makes little sense to many workers, as flatter and leaner organizations have become customary practice. Workers who are now in their 20s and 30s might change jobs several times, preferring better benefits to upward mobility. In other words, "up is not the only way" (Kaye, 1985). This reality has forced an evaluation and reengineering of traditional practices that are based largely on the notion that any loyal employee can move up the corporate ladder.

Leaders of organizations generally have one view of employee development, while HR and career development professionals have another. Organization leaders frequently believe that exemplary performers will automatically rise to the top, most probably without a need for organization-sponsored employee development. This belief is often bolstered by the fact that many employees look for ways to become upwardly mobile.

HR professionals and career development professionals have separate but overlapping perspectives on employee development and the purposes it should serve. On one hand, the HR camp tends to see employee development primarily as a process that increases employees' usefulness and marketability within the organization—and only secondarily as a means of encouraging employees to explore their life-career interests, values, and goals and to discover ways that the organization's employee development opportunities might help them achieve their life-career goals.

To career counselors, on the other hand, a career is the sum total of an individual's values, aptitudes, interests, motivations, education, competencies (including knowledge, skills, mind-set), training, work, and other experiences over an entire life span. Life choices are guided by the individual's personal values. In their view, it is the organization's responsibility to provide development opportunities that will help employees to achieve their life-career goals as well as improve their work performance. These two camps must join forces if employee development is to thrive and be fully integrated as a value-added HR management component.[1]

In this chapter, we address the following key questions:

- What is employee development?

- How is employee development traditionally carried out?

- How can employee development become competency-based?

- What are the advantages and challenges of a competency-based approach to employee development?

- When should employee development be competency based, and when should it be handled traditionally?

[1]Employee development is a broad field, and those who pursue this work must be conversant with a wide variety of concepts, ideas, and facts. We suggest the following references: Fredrickson (1982); Hafer (1992); Harris-Bowlsbey, Dikel, and Sampson (1998); Kapes and Whitfield (2002); Kummerow (2000); Leibowitz, Farren, and Kaye (1986); Niles (in press); Niles, Goodman, and Pope (2001); and Pope and Minor (2000). For extensive applications of the concepts discussed in this chapter, see Anonymous (1993, 1995); Delahoussaye (2001); and Patch (2000).

Employee Development

As is the case with most professions, vocabulary is essential to framing a context for employee development. Accordingly, we have defined several key terms that are commonly used in organizational HR practice.

Organization development consists of activities that are directed specifically toward improving the effectiveness of a total organization or its subgroups.

Employment can include an individual's self-employment, working for an organization, or volunteering, or activities such as homemaking and relationship building.

A life-career is the integrated progression of an individual's life- and work-related activities, including the identification, development, and pur suit of aspirations in accord with his or her personal values over an entire life span.

Training is an individually focused change effort pursued by an employee for the purpose of learning specific behaviors that are needed for immediate performance of work. After training, the employee is expected to produce outputs or results of the required quality.

Development refers to any effort to acquire competencies.

Employee development is the pursuit of any activity that leads to continuous learning and personal growth and contributes to achieving both the individual's and the organization's objectives. It is a continuous learning process that deepens an employee's understanding of his or her values, interests, skills, aptitudes, personality attributes, and competency strengths. Competencies acquired through employee development are usually intended for future application. The links to competency-based HR planning are obvious.

Employee development is thus a process that continues throughout an individual's life span, regardless of employers or type of employment and individual experiences. What is so interesting about this process is that it evolves and often occurs whether or not employers explicitly support it as an organizational commitment. When an employer supports employee development as a business investment, however, the organization can realize enormous benefits.

Although employee development is essential to the long-term success of organizations today, organization leaders generally classify expenditures for employee development as a cost on financial statements. Persons who intend to create an employee development process must address this incorrect mind-set from the outset. Organizations should note that they either pay now or will pay later. The "pay later" will manifest as unprepared employees, lack of talent brought on by less ability to attract and retain exemplary performers, and a reduced knowledge base across the organization. These conditions might occur at a time of crisis, when playing catch-up can have dire implications for the organization. Decision makers must understand that unless the organization invests in its future growth by making long-term improvements in its competency pool, it will pay the price for not doing so at a later time.

The philosophy, framework, and objectives of an employee development effort must be well conceived if they are to align with and support achievement of the organization's goals as well as those of its employees. Senior leaders must consider the reasons for sponsoring a developmental process from both perspectives: the organization's and the employees'. For example, an organization needs an individual who can apply a specialized competency or competency set so that it can benefit by growing, developing brand loyalty, and increasing revenues. At the same time, an employee who possesses the necessary competencies needs an arena in which to perform while addressing his or her life-career preferences. Matching these two sets of needs is at the heart of employee development.[2]

Yet, even after the development process has been tailored to organizational and employee needs, disconnects frequently occur. The organization may begin to view employees as less important than completion of work, and, employees may seek upward mobility in return for their contributions. For this reason, all communications about employee development must be accompanied by a clear purpose statement and—of critical importance—must inform potential participants that the organization makes no guarantees of promotion. Being assigned work at a greater level of sophistication or receiving a promotion gives an employee a sense of status and personal power and traditionally represents validation by the organization. Opportunities for upward mobility are limited, however, and individuals must understand that they are being developed only for reasons consistent with the program goals. This concept of development is hard for employees to grasp and difficult for the organization to ignore. Perhaps as a reflection of employee attitudes, organizations often rate the success of development programs by the number of promotions, instead of by the degree of life-career satisfaction experienced by employees. Both employees and their organizations benefit when career planning and guidance are part of the employee development process.

Walker and Gutteridge (1979) stated that many organization leaders regard career planning and development programs as serving several purposes, such as to enhance job and work performance, enable employees to utilize the organization's HR systems more effectively, and improve the organization's ability to use its talent. Other researchers noted that an organization-sponsored career planning and development program also reduced employee turnover, supported organizational efforts to comply with diversity and equal employment opportunity requirements, and encouraged employees to assume greater responsibility for their careers (Cairo, 1985).

[2]For information on creating a development culture in an organization, consult Simonsen (1997).

Traditional Employee Development

Explaining traditional employee development is challenging for a number of reasons. First, employee development may not be well defined by organizations that express an interest in it, and when definitions are given, they are usually inconsistent. Second, the leaders of some organizations do not view organization-sponsored employee development as a driver of organizational success. They do not realize that it might be necessary to provide even modest support to employees in meeting their competency or life-career development objectives or that by doing so, both the organization and their employees would reap rewards from their mutual efforts. These employers are usually surprised when employees attain development objectives on their own and then leave for jobs elsewhere. This is not to say that organizations do not have employee development approaches, but many of these applications are not part of a formal, well-defined process of development, and, consequently, the degree of success achieved through traditional practices is often unclear.

Career Telling

Typically, a supervisor asks an employee, usually during a performance review, about his or her goals and where the employee wants to be in the next 5 or 10 years. Supervisors generally direct this question to an employee's work situation and pay little or no attention to life-career issues. Because employees probably have not thought about these questions beforehand and do not have a total life-career picture in mind, they give on-the-spot responses that are not necessarily valid. In most cases, therefore, the answers are general and nebulous. Supervisors usually react by telling employees what would be occupationally or vocationally best for them. For example, a supervisor tells an employee, "You're really good at customer service. I think you should get a business degree with a major in sales. You'd be good at sales." The employee is flattered and develops expectations such as tuition grants, taking time off from work, obtaining child care support while pursuing his or her studies, achieving an eventual promotion, and attaining other such rewards. After the review, the employee acts on the supervisor's suggestion and obtains support to pursue the first development step, taking a sales course. The employee completes the course, discovers that two more courses are needed, and returns to the supervisor for additional support for these courses. Later, the employee returns to the supervisor and asks for a special assignment that will test the newly acquired competencies. The supervisor, who is in fact stalling for time, complies, but this still is not enough to meet the employee's expectations. Then, with no notice, the employee is terminated in a downsizing operation.

This cycle of transactions is known as the "hush puppy" effect. Think of the events described above in the context of the following analogy. A cook is frying cornmeal treats when a puppy begins to bark nearby. In order to "hush the pup", the cook throws him a cornmeal treat, and the puppy leaves the room—a hushed puppy. The puppy departs, only to return when he is hungry again. He receives another "hush puppy" (which, by this time, he has begun to expect from the cook) and is again satisfied for a while. But since cornmeal treats do not provide adequate nutrition, the puppy fails to grow and never becomes an adult dog, and he continues in this "no growth" situation. In retrospect, the cook was not doing the puppy any favors by giving him the supposed treats.

This is often the sequence of events and the outcome that results from a career telling approach to employee development. Employees fail to grow in meaningful ways and stagnate unless an appropriate employee development experience stimulates them to take responsibility for their life-careers. This unfortunate outcome could be avoided if the supervisor were aware of the employee's competence and life-career needs or preferences and the employee were aware of her responsibility for managing her own life-career. Addressing either one of the two components affects the other. The "hush puppy" is an excellent example of a procedural development process.

Choosing Work

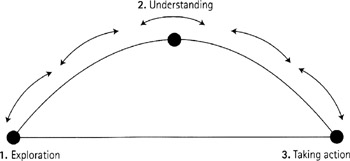

Figure 12 illustrates a three-step process for choosing the correct work. Achieving work satisfaction begins at Step 1, when employees express an interest in exploring opportunities within the organization. At Step 2, they become engaged in understanding their options in terms of their own values. And, finally, in Step 3, they act on one or more of their options or opportunities. Career telling generally does not follow this progression.

Figure 12: The Three-Step Process for Choosing the Correct Work

For example, an employee approaches his career telling supervisor with a perceived need to explore his work options or opportunities and his personal values as they relate to those options. During the discussion, the supervisor starts at Step 1 but immediately moves the employee to Step 3, completely bypassing the understanding stage. Yet career telling works only when the employee understands the relationship between his values and the options or opportunities he identified in Step 1. An individual's values and their intimate connections to career choice and job satisfaction cannot be ignored. When employees do not understand their own values, or when the values of employees and organizations do not match, employees eventually leave for other positions, either within the organization or outside it (Schein, 1978). From a counseling perspective, work values are often an unnamed motive for an individual's life-career changes.

Some organizations, however, do not take their employees' value systems into consideration. A well-known example is the promotion of a technical expert to a supervisory or managerial position based on the incorrect assumption that because the employee is an excellent technical performer, she will be equally expert in a new work role. The promotion often sets the employee up for work failure, since the new role may require the use of previously unneeded competencies. The following questions should have been answered as part of Step 2:

- Is the new work role consistent with the employee's values?

- Does the employee possess the abstract, nontrainable competencies required for success in the new job? Can the employee appropriately use these competencies upon commencing the new job?

- Is the employee motivated to acquire and apply the other competencies needed for job performance success?

Moving directly from exploration (Step 1) to taking action (Step 3) predisposes the employee and the organization to failure and cheats the employee out of an opportunity to develop self-awareness and make a solid career choice—to accept the promotion or to decline it and possibly leave the organization. Bolles (2002) noted that many organizations are sometimes reluctant to provide time for developmental understanding of work opportunities because the employee might decide to leave the organization. However, as the following example illustrates, this outcome, too, can be beneficial, both for employees, who are able to pursue work that matches their values and motivations, and for organizations, which have helped potentially frustrated and unproductive employees to discover careers that are right for them.

An individual was employed by the U.S. Postal Service as a letter carrier. The employee later realized that this type of work was not a good career fit. A career fit is defined as a work choice that balances the person and place with the work the person performs. In this example, the person and place were congruent, but the position was not. The letter carrier engaged in an organization-sponsored employee development planning process that placed heavy emphasis upon the use of the "explore, under stand, take action" process. Following completion of the process, the letter carrier resigned and started his own business. He credited the Postal Service by saying, "I realized the position was not suited for me, and the Postal Service helped me to make a better job match. I credit the Postal Service as an organization that cares about its employees and that helped me to realize my potential. I owe the Postal Service." An excellent investment in people and a great public relations outcome for the Postal Service resulted from these transactions. Everyone won with this approach. The Postal Service does not have an unhappy, frustrated, and possibly unproductive employee, and the employee is pursuing a work path that matches his values and motivations.

It is important to keep in mind that this process does not necessarily proceed linearly. Individuals may begin at Step 1, complete Step 2, and then return to Step 1, usually because, after developing an understanding of the decision and its impact, they are not satisfied that they have chosen correctly. For similar reasons, individuals may explore, understand, take action, and then return to the understanding stage months later, seeking deeper insight into their choices or values.

Other Approaches

Some organizations have designed and implemented employee development initiatives, which are known, for example, as career, career management, or career development programs. The problem is that, in an organizational context, program usually means there is a beginning and an end. These programs seldom receive rigorous evaluation of their contributions to organizational and employee well-being, and, unless they are viewed as strategic to the organization's immediate success, they are frequently the first to disappear when spending is curbed. Yet many of these approaches can be not only strategically essential, but beneficial for both employees and their organizations when applied as part of a planned process of continuous employee growth. A process implies that there is a start with no particular end.

Many employee development programs include sessions on filling out an application, locating promotion opportunities, conducting one self in an interview, getting a special assignment, and similar subjects related to an employee's tenure with the organization. Other programs offer education, for instance, on daily living or basic skills, team building, leadership, and visioning. In our experience, few of these programs have a long-term, significant impact on either individual development or organizational success—as some leaders have learned as cost-benefit results became more available.

Workshops

There are many topics featured in employee development workshops. Some may include, for instance, topics such as assessment of personality type (for example, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator instrument, available from CPP, Inc.); determination of interests, preferred work style, or preferences for conflict resolution; interpersonal relationships; and oral or written communication.

Individual coaching and mentoring

Supervisors, managers, or expert coworkers typically provide individual coaching for employee development activities. In organizations today, the goal is very often improved performance, which makes this type of coaching a component of the performance management process. Mentoring is closely related to coaching, but the relationship between mentor and protégé is sometimes not clear to either. Protégés may believe that their mentors will guide them toward promotions or another form of advancement in their work lives. Mentoring offers wonderful opportunities for employee growth, but misimpressions, unrealistic expectations, and other dynamics associated with mentoring may possibly ruin what can otherwise be a mutually beneficial relationship.

Toastmasters, Inc.

This group has a number of organization-based chapters throughout the United States and elsewhere. Its first objective is to support employees in acquiring presentation and public-speaking skills. This is an extremely successful developmental activity since employees initiate their own participation in this developmental process. In addition, they receive performance feedback from peers who are also participants, thereby creating an ongoing development support system. This activity can be done at little cost to the organization.

Workbook exercises

These activities are self-motivated and usually self-paced. They cover a variety of work-life topics, such as informal values assessments, occupational interest assessments, introduction to occupational areas, labor information, and sources of support for life-career management. Many exercises can be found on the Web and can be quite helpful, but it is also very beneficial to conduct life-career assessments with the guidance of qualified career counselors.

Career path systems

With this approach, employees learn about the requirements and procedures that apply to moving from one work situation to another. Although used largely in government and military settings, it may also be useful and offer tremendous value in private sector firms, especially those organizations in which upward mobility is possible. In such firms, a career path system can provide competency and performance guidelines for advancement.

Skills bank

This activity was an extremely popular form of organizational career development during the 1970s and 1980s, and despite its pitfalls, it is still used by some organizations today. An organization creates a skills bank by collecting data from employees on their education, experience, interests, knowledge, and perceived competencies (which the organization usually refers to as "skills"). After the information is returned to the skills bank manager, employees wait for the organization to take action on their career development. Unfortunately, organizations often collect the information but have no clear plans for organizing it or using it to anyone's benefit, even their own. Employees may wait years to be noticed when an organization is primarily responsible for their development.

Temporary assignments or detail job listings

Organizations sometimes post lists of employees who are seeking temporary internal assignments. As positions become available, managers consult the list and may select individuals for consideration. This does make selection a direct process, but it also raises issues of possible discrimination, favoritism, and lack of fairness since, in most cases, not every person who expresses an interest can be awarded an assignment.

Educational programs

These programs often provide college or university tuition reimbursement and support for employees who attend external seminars, workshops, conferences, and similar events. Organizations may also contract with a provider to offer an internal educational program when the program would benefit a significant number of employees.

Computer-based career guidance systems

These automated and highly sophisticated systems can be used independently by employees, with support from an employee development facilitator, to assess their values, beliefs, occupational preferences, personality type, and similar attributes via a highly structured computer program.

Competency assessment activities

Multirater competency assessment, or 360-degree feedback assessment, is increasingly being used by organizations today. With 360-degree feedback, competency assessment results are usually reviewed by the employee's manager or a performance coach, or by both. The feedback leads to development planning and a systematic employee development process. Peer review is a simplified version of the 360-degree assessment and is generally used for supervisors and higher-order managers. It helps individuals to obtain feedback on their performance from coworkers and to determine the effects of that performance on the achievement of work objectives.

Assessment centers

An assessment center is a formal, structured competency assessment mechanism. It consists of simulation and other assessment activities that use multiple raters to determine an individual's competency strengths and performance preferences in various settings similar to the person's work situation.

Making Employee Development Competency Based

To some extent, many employee development initiatives have functioned as a response—to a crisis or a trend—rather than a strategic, long-term HR component designed to provide the organization with the necessary bench strength when the organization needs it. What is missing in many employee development efforts is a strategic link that aligns the organization's long-term success with its employees' competencies and life-career needs and preferences in ways that benefit both parties.

Why should organizations take a competency-based approach to employee development? Cafaro (2001) noted, in citing comments made by David Messinger at the 2000 Worldat Work International Conference in Seattle, "To win the proverbial war for talent, managers should focus on involving people strategically and investing in their career ambitions, even at the risk of losing them." Many workers are interested in understanding their place in the overall organization, and this fit can be defined in terms of how well each one contributes his or her talents in meaningful ways to the organization's competency pool. Cafaro in the same article singled out opportunities for advancement and challenging work as among the top reasons for joining and staying with a company, explaining that "many topflight employees are apt to be more energized by the intrinsic value and longer term payoff of education and selfimprovement than the monetary value of a pay raise."

No longer is salary necessarily the reason for employees to leave one organization for another. Schein (1978) noted that individuals have unique needs and require a performance arena in which those needs can be met. If the current work setting does not provide an appropriate arena, they will seek another one, perhaps in a different work assignment in the same organization or in another organization. Consequently, it is to an organization's advantage to achieve the greatest alignment possible between its employees' work and life-career preferences and the work it needs to accomplish.

Our approach to competency-based employee development serves as the essential strategic link between organizations and their employees by emphasizing the development of worker competencies and global competence in ways that benefit the organization as well as the worker. Both workers and organization leaders must be satisfied with their answers to the question "What's in it for me?" A competency-based approach shifts the focus from job-specific training to development of competencies that can be applied in many situations.

To ensure that employee development is competency based, senior managers need to endorse employee development plans that address two key issues. First, the effort must develop those employee competencies that are aligned with achievement of the organization's strategic business objectives. Second, the plans must also address employees' issues in identifying and meeting their life-career needs.

The Advantages and Challenges of Competency Based Employee Development

It is important to bear in mind that competency-based employee development is not a panacea for performance problems stemming from low employee morale, dysfunctional corporate culture, poor management, and other similar conditions. Organizations must separate competencybased efforts from work performance observations. Those concerns aside, there are major advantages to implementing a competency-based approach to employee development.

The process enables senior managers to communicate the organization's competency needs in a clear, straightforward manner to all employees. At the same time, its use expresses management support of employees, who are viewed as an important factor in organizational success. A comprehensive competency-based process provides employees with the tools for taking charge of their life-careers and work development by exploring and understanding their interests, values, aptitudes, personality factors, current areas of competence, and the competencies they need to build for future life-work roles and responsibilities. The concept of life-career becomes an integral part of the organization's employee development philosophy.

There are also key challenges to adopting a competency-based employee development process. A competency-based approach requires commitment to front-end competency identification and modeling, which can be a major undertaking. Competency-based employee development is intimately linked to the concepts, practices, and outputs of a competency-based HR planning system. Without such a system in place, the employee development manager might not be able to produce sound results.

Some employees may choose to leave the organization after reviewing their competency and life-career assessment results and realistically evaluating their opportunities in the organization. Employees who depart will most likely do so amicably after taking part in an employee development process. If not communicated properly, a competencybased development process could be misinterpreted by both managers and employees. For example, managers might see it as a means of providing outplacement services, while employees could view their participation as an indication of future promotion or other major advancement in the organization.

Deciding on Competency Based or Traditional Employee Development

An appropriate organizational setting for implementing a competencybased approach requires decision makers who are willing to commit the necessary resources to the design, development, implementation, and maintenance of a competency-based process. Effective planning and implementation demand sufficient lead time as well as a competency-based HR planning system to clarify future talent needs and operate in conjunction with the development process. The organization must be prepared to invest in leaders, managers, supervisors, and others to provide ongoing support of its employees' development, for example, by coaching or offering direction and feedback. Leaders must also train and assign at least one employee to serve as an employment development facilitator.

The corporate culture must support employees in taking responsibility for identifying their life-career needs or preferences and their work-life progression. For example, leaders could provide the opportunity for employees to select and meet with a career advisory committee, consisting of the employee, his or her supervisor, an HR practitioner, and a peer. The committee might address topics such as the employee's competencies or competency needs, interests, development objectives, and plans and offer honest feedback and suggestions. Senior managers must accept employee development as a long-term process that integrates workers' life-career concerns with the organization's strategic goals and objectives and requires sustained commitment.

Implementing Competency Based Employee Development

Implementing a competency-based approach in one component of an HR management system does not necessarily require competency-based practices throughout the organization. This is perhaps more true of employee development than of any other process. Because employee development as a key work unit is sometimes an afterthought, it frequently can be found in silos within the organization, such as operations, human resources, diversity, quality, or training. Nevertheless, the design, development, and implementation of a competency-based employee development process can be a daunting task for even the most seasoned HR professional.

Typically, an operations manager approaches an HR executive about the need for a competency-based employee development process for a particular group of workers. The manager probably does not say "competency-based" or even "employee development," but the HR professional usually understands that the request has nothing to do with short-term training.

It may be advisable to contract an external consultant if expertise in competency-based employee development is not available in the organization. The consultant's tenure in the organization and the work to be completed should be well defined and planned before work begins. The consultant can also provide oversight of the start-up process and perhaps conduct some of its activities. Employees who participate in the creation and implementation of the competency-based process will develop the sophisticated competencies needed to maintain and improve it, which makes the organization's investment well worth the cost in the long term.

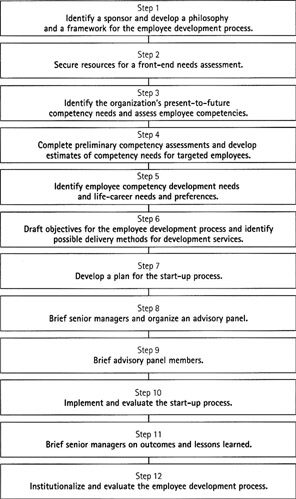

Figure 13 depicts our model for creating, implementing, and maintaining a competency-based employee development process. The following step-by-step discussion provides instructions for the model. Additional suggestions on designing and implementing a competencybased employee development system can be found in Appendix B.

Figure 13: Implementing Competency-Based Employee Development

Step 1: Identify a sponsor and develop a philosophy and a framework for the employee development process

An organization's HR department is the logical sponsor for a competencybased employee development process. If resources are not available in the HR department, however, the manager with the most urgent need for a competency-based development initiative can also sponsor the program. A member of the HR department generally shares joint responsibility for facilitating the initiative with a representative from the sponsoring manager's staff.

The organization must decide at the outset on a philosophy for the employee development effort; the framework of the process will be built on this foundation. For example, an organization could adopt a life-career philosophy, thereby endorsing the concept that development is a holistic, continuous process. A framework consistent with this philosophy would provide initiatives that help employees to create development plans expressive of their work preferences, leisure activities, learning, families, and other dimensions of their lives.

In most organizations, the employee development process must effectively serve a diversity of persons from several generations of workers. Today, for example, baby boomers are working side-by-side with Gen-Xers and senior citizens. Consequently, organizations that create an employee development process must accommodate these generational differences in planning their service options and delivery methods.

All stakeholders must develop a clear understanding of the words used to describe the competency-based employee development process and its objectives. Vocabulary is critical to explaining how employee development will interface with other HR management initiatives and address the needs of other work units. It is also important in managing employee expectations of the process. All competency-based HR management practices are interconnected, not only within the HR function, but across the organization.

Step 2: Secure resources for a front-end needs assessment

The competency-based employee development initiative, like every effort that could have significant impact on the organization, should undergo a front-end needs assessment. Senior leaders will require considerable data about employees' competencies and life-career issues and the organization's competency needs. Without this information, obtaining their support for such an effort will be very difficult. Organizations with no competency or employee development practices in place will require resources such as the following:

- At least two computer workstations with the necessary peripheral equipment

- Office space, furniture, supplies, secure storage, telephone, fax

- Valid and reliable competencies for the work to be completed by participants

- Life-career resources such as personality assessment materials, occupational interest inventories, access to the Department of Labor's O*Net on the World-Wide Web, appropriate software systems, and values determination or clarification instruments (see Step 5 for further information on life-career issues)

- An external consultant or contractor with competency-based employee development expertise, such as a professional career counselor or certified career development facilitator, if the necessary experience is not available internally

- A research resource who can set up, administer, analyze, and report the findings of employee surveys, interviews, and similar data collection and analysis tasks

Step 3: Identify the organization's present-to-future competency needs and assess employee competencies

In identifying competency needs, it is important for the sponsor or senior leaders to specify which employees will be customers of the employee development process, as this will determine both the competency sets and the characteristics of the employee development process. It is important to keep in mind that these characteristics could become constraints when the client base for employee development is expanded to other competency sets and employee groups.

In the context of this process, the organization's competency needs and employees' competency requirements are the same. The elements to be defined are simple: Here is the work that must be done, here are the persons (or types of persons) who are available to do that work, and here are the competencies they must possess and use in appropriate ways to achieve those work objectives in a fully successful or exemplary manner. If a competency-based HR planning system is in place in the organization, then the information needed for this step is already in the planning system. Without an HR planning system, the HR practitioner must identify the competency sets that will become the foundation for the employee development process. (Competency identification is a complex topic. If necessary, review the discussion in Steps 4, 5, and 6 of Figure 3 in chapter 4.)

Identifying present-to-future competencies is challenging when work that has not yet been performed must be defined and assessed first for outputs or results and then for competencies and behavioral indicators. It can also be daunting to identify competencies and behavioral indicators for work when the current performance emphasis must be modified so as to improve the quality of the outputs. These uncertainties, of course, affect the accuracy of the predictions. When employee development targets the wrong competencies, the error can be costly in terms of resource investment and credibility. Consequently, this step must be carefully carried out.

The most direct way to identify competencies is to determine the organization's strategic goals and business objectives and, from those, the results employees must produce if they are to demonstrate successful or exemplary performance. These required work tasks should be stated in clear terms, grouped in a meaningful manner, and then analyzed for competencies and behavioral indicators.

When work elements are analyzed for competency identification purposes, three types of competencies will result. The first type consists of functional or technical competencies peculiar to the specialized nature of the work. The second type includes those required for successful daily living or basic skills, such as reading and arithmetic. The third type includes the more abstract competencies employees use in performing work, such as the capacity for patience or the ability to effectively accommodate ambiguity. Several methods of identifying competencies are currently in use, and new methods become available as the practice evolves. Each organization must select an approach that will yield comprehensive, accurate results and is also practicable, given its circumstances.

If the use of highly rigorous competency identification and modeling methods is not possible, HR practitioners might consider making a high-quality preliminary identification of competencies for the subject work and the target population. To do so, we recommend the modified DACUM process, which is one of the competency identification methods described in chapter 2. This method produces competency sets that are sufficiently accurate for needs assessment purposes. Our experience with the modified DACUM process suggests that it tends to overidentify rather than underidentify the competencies required to perform the subject work, depending on whether it is being performed at that time or is to be performed in the future.[3]

Step 4: Complete preliminary competency assessments and develop estimates of competency needs for targeted employees

Supervisors or managers judged to be experts in the work that must be performed and who are familiar with the performance of the subject employees are the best sources of information for the preliminary assessment. Assessors should evaluate only those persons about whose performance they have firsthand knowledge. The ratings could also be validated by an assessor's immediate superior, if that individual also has direct knowledge of the subject employees' performance. In short, the preliminary competency assessment data should be of the highest reliability and validity possible.[4] (See the discussion of Step 7 of Figure 3, which describes competency assessment for HR planning purposes, in chapter 4.)

Step 5: Identify employee competency development needs and life-career needs and preferences

We have already defined employee development as the pursuit of any activity that leads to continuous learning and personal growth and which contributes to the achievement of both individual and organizational objectives. For employees, there are two types of development needs: competency development needs and life-career needs and preferences.

These needs are assessed separately using different approaches. After data from both domains become available, HR practitioners integrate each participant's information into a competency and a life-career profile. The organization plays a major role here in designing the frame work for the accomplishment of this work and thereby ensuring that data and interpretations are handled and communicated appropriately to participants. The information in the profiles should help managers to match employees with work that potentially is consistent with their needs and preferences. Because the development of this composite profile depends on the types of data collected and the purposes of the employee development process, the following suggestions should be considered general guidelines for proceeding.

We begin with competency development needs. By comparing the organization's present-to-future competency needs with the competency strengths of employees, the HR practitioner can identify and quantify competency gaps. A profile of those competencies can be easily constructed by placing the information in a two-by-two matrix composed of identical columns and rows. The rows could be assigned to participants' competencies and the columns to the competencies required by the organization. A check mark in a cell of the matrix would indicate that the employee in that row possesses the competency to the strength needed by the organization. HR practitioners can depict more detailed information by using a strength rating instead of a check mark. Keep in mind that not every participating employee needs to possess every competency and at the same strength. This information will be significant in designing competency development for individual employees.

The three types of competencies noted in Step 3—functional or technical, daily living or basic skills, and abstract—could affect the organization's ability to realize successful or exemplary work performance. HR practitioners can classify and identify competency development needs and match them to development opportunities by using these three categories. The first two types of competencies are, almost without exception, trainable, but the third type, the abstract competencies, probably cannot be acquired through training or other developmental experiences. Abstract competencies require especially creative strategies for identifying or creating development opportunities. Each organization must devise an approach that is situation specific. It is best to remain flexible and open to suggestions as start-up activities unfold. Listing the three types of competencies against needs will help the start-up process manager to determine the resources required.

Next, we consider life-career needs and preferences. The life-career dimension of employee development includes a large body of knowledge, skills, practices, and techniques and encompasses career counseling, HR development, psychotherapy, organization development, training, knowledge management, and industrial psychology. Although HR practitioners will not do in-depth life-career assessments and profiles until the start-up process is well under way, a life-career perspective on employee development will help in planning a competency-based development process that includes life-career practices as a key element. This step requires only a preliminary assessment of participants' life-career needs and preferences appropriate for pilot study purposes.

There are as many explanations of life-career needs and preferences as there are theorists. In our experience, however, the following six lifecareer needs have been mentioned repeatedly by clients in organizational settings and in private practice:

- A need to achieve, motivated by the desire for personal competence and self-mastery.

- A heed to produce work results or outputs with perceived value, or, in other words, finding work that has personal meaning.

- A need to perform work that is personally enjoyable.

- A need to exercise a degree of control over the performance of one's work activities as well as when and under what conditions one performs work.

- A need for quality information, time to process the information, and an arena in which employees can use the information to actively pursue their preferences.

- A need for time away from work for activities such as, for example, hobbies, recreation, care giving, independent learning or personal growth, physical rest, and spiritual development.

This final need raises a critical point regarding the design and implementation of an employee development process. While employees are engaged in a development process, they need to understand that their total sense of satisfaction will not come from their worker roles. As Bolles (2002) noted, satisfaction comes from an integration of life roles and activities that include work, leisure, learning, and family. The life-career concept is a major philosophical change for a typical organization. It not only directs attention to facets of life other than work but also stresses that success is not confined to advancement in an employee's work-for-hire.[5]

An organization needs a collective inventory of employee life-career needs and preferences if it intends to address these issues. Probably the best suggestion we can offer, in terms of time and expense, is to organize a focus group that is representative of all the participants. This group could consist of up to 20 persons if necessary. By conducting a facilitated discussion, HR practitioners can create a comprehensive list of life-career needs and preferences as expressed by the group members. To ensure additional comprehensiveness, a panel of subject-matter experts can review both the list and the draft questionnaire assembled from the list. The final document incorporating their suggestions and revisions can then be distributed to all start-up participants, instructing them to select their five highest-priority, most critical life-career needs or preferences and to rate the importance of those five needs or preferences relative to their current or anticipated life and work circumstances.[6] The data, once analyzed, provide a very comprehensive understanding of participants' life-career needs and preferences and will be useful in making additional plans. If participants agree to place their names on their questionnaires, management will be able to consult these personalized records of their life-career preferences when considering work assignments and development opportunities. Further examples of life-career assessment exercises can be found in Appendix C.

Step 6: Draft objectives for the employee development process and identify possible delivery methods for development services

The objectives for any competency-based employee development process will differ somewhat across organizations; however, facilitators of the effort may want to include one or more of the following statements of objectives among their own:

- To ensure an adequate and balanced competency pool so that the organization can achieve its strategic goals and business objectives

- To communicate to employees the organization's support of their continuous learning and the understanding and pursuit of their lifecareer preferences

- To ensure that work assignments are aligned with employees' competency strengths and the successful pursuit of their life-career preferences

- To serve as an employment incentive to attract exemplary performers

- To encourage the retention of fully successful and exemplary performers

- To provide less productive employees with self-insight in an ethical and professional manner and encourage them to take responsibility for their daily work and life-career preferences, possibly including outplacement

There is an astounding range of approaches available for providing employee development services, even in geographically isolated areas. Candidates for learning opportunities include the following:

- Web-based and distance learning

- Embedded learning

- On-the-job learning with peers or site-assigned facilitators

- Coaching from a supervisor, manager, or executive

- Professional counseling, career counseling, or assistance from a certified career development facilitator

- Management discussions

- Workbooks or other self-directed learning media

- Computer-based career guidance systems

- Professional or trade conferences, seminars, and workshops

- Job or work rotation

- Learning opportunities provided by labor or other organizations

- Group-based life-career exploration or planning activities

- Community college, 4-year college, and university courses or other offerings, including adult or continuing education

- Community-based adult or continuing education

- Employee-initiated learning projects (for example, self-study projects, reading programs)

Step 7: Develop a plan for the start-up process

Competency-based employee development initiatives can be difficult to implement and may not be fully accomplished in one attempt. Those who pursue this approach must maintain a realistic mind-set and expect to learn as they go. Process milestones should be marked by reasonable objectives, taking into account the resources available and organizational attitudes toward the process and its outcomes.

The following items should be reviewed before beginning development of the start-up plan:

- The organization's strategic goals or objectives

- The competency needs to be addressed

- Competency assessment data for participating employees

- Estimates of participating employees' life-career preferences, the effect of those preferences on the achievement of work, optimal placement of employees to complete that work, and employees' competency development needs.

- Estimates of the types and volume of employee development activities needed to close competency gaps

- Summary of participating employees' life-career preferences and the impact on meeting work placement and competency development needs

- The time frame for completing start-up activities

- Possible roadblocks to achieving start-up outcomes and ways in which to overcome them

A well-conceived start-up plan will go a long way toward creating a high-quality employee development process that will be valued by organization leaders. Producing a tight yet flexible plan is well worth the investment of time and effort. The start-up process manager should confirm that the plan meets the following criteria:

- Is absolutely consistent with the start-up process objectives

- Uses only those resources that management has already committed to completion of the project

- Is easy to understand

- Is automated so that it can be easily modified, annotated, and distributed

- Communicates the agreed-upon results or deliverables needed for project success

- Includes tasks required to produce administrative and other documents for key project stages (the time and effort needed to produce or acquire these items is often underestimated)

- Includes tasks and time needed to obtain, review, evaluate, or implement vendor products such as a computer-based career guidance system

- Begins identification of process evaluation activities

The start-up manager is responsible for providing ongoing internal communication on start-up design and implementation. A standardized project-planning matrix makes this task easier. Each row of the matrix states a major project task and, below the task, any key subtasks that are of critical importance for successful performance of the work. The columns of the matrix list details for each task. These details should include, at a minimum, the task output, result, deliverable, or outcome; target completion date; actual completion date; resources assigned to the task; and inputs to the task, such as earlier deliverables, materials, decisions, and so forth.

Step 8: Brief senior managers and organize an advisory panel

With the information collected and developed in the previous steps, the start-up process manager is now well prepared to brief the organization's senior leaders on the project. The main objectives of this briefing are to ensure the following:

- Senior leaders understand the need for certain employee competencies as part of the organization's talent pool. The critical data to support the need should be presented and explained in detail. Leaders must also understand the consequences if these competencies are not available when required for organizational success.

- Senior leaders understand the advantages of taking a holistic view of employee development by accommodating employees' life-career preferences while developing their competencies and making work placement decisions.

- Senior leaders are prepared to commit the resources needed for a successful start-up.

Senior leaders should also select an employee development advisory panel and compile a list of responsibilities for panel members. The advisory panel will be charged with reviewing, assessing, and reporting on the project and will make recommendations on implementation to the start-up process manager.

Step 9: Brief advisory panel members

Advisory panel members should receive the same briefing as the senior managers. It is especially important that they understand their specific responsibilities and the timetable for carrying them out. Panel members offer a no-fault environment for preliminary testing of start-up instruments, procedures, and techniques, which may then be revised as needed. They could also engage in process activities, such as life-career assessment and debriefing, that participating employees will complete after the system is implemented. Advisory panel members have an integral role in reviewing and interpreting process evaluation information and recommending improvements. They should be available to the start-up process manager on an ad hoc basis as needed.

Step 10: Implement and evaluate the start-up process

There is no one way to implement a competency-based employee development process. Each organizational setting requires its own unique approach. The following suggestions for implementing and evaluating the process therefore represent general guidelines only.

First, HR practitioners must confirm that the required resources—space, personnel, materials, and related support mechanisms—are in place and ready for immediate use. A premature launch could result in failures, employee and management dissatisfaction, inappropriate use of established employee development practices, ethical violations, compromised confidentiality, employee assessment errors, poor service delivery, and other unfortunate occurrences. Since credibility is essential in this particular HR application, it is advisable to delay implementation rather than risk a disaster.

Second, the sequence of activities should ensure that the approach is indeed systematic. Organizational circumstances must dictate when and in what manner these steps are taken, but the following are the minimum that must be completed by the start-up process manager:

- Continue to review the process philosophy and objectives and all agreements made with sponsors, organization leaders, and HR practitioners. Make changes to all agreements as circumstances warrant but be certain to communicate those changes in a timely manner to all parties with a need to know. Ensure that communications are complete and accurate.

- Review the specifications for the targeted employees and prepare an electronic participant database, using the HR information system if possible. The database should include, at a minimum, each participant's name, work unit designation, work location as a street address, telephone numbers, e-mail addresses, and position title. Collect the same information from the participants' supervisors.

- Brief participating employees, their supervisors, and employee development advisory panel members on anticipated objectives and outcomes as well as plans for start-up activities and the role each group will play in these activities. The timing and content of this preliminary briefing could be somewhat problematic. It is essential, on one hand, to build interest and enthusiasm but, on the other, to avoid creating rising expectations about project services or outcomes. Organizations today face rapid change and sometimes must accommodate business crises by modifying employee development priorities.

- If it has not yet been done, complete multirater competency assessments for the key competencies to be addressed by the participants. Valid competency assessment data are essential to project success.

- Identify the elements that will constitute the life-career component of the employee development process. For example, what lifecareer assessment instruments will be used, who will administer and score them, and how will the results be interpreted to participants? Are certifications required? What are the requirements for maintaining the security of the assessment results? Are confidentiality agreements understood, and can they be met within organization operations?

- Develop practices for linking and analyzing competency assessment and life-career preference information and communicating the data to participants. Decide on the briefing protocol and select the persons to conduct the briefings. Should an employee need further development counseling after learning about his or her assessment information, how will these services be identified and made available in a timely and appropriate manner? What payment source will fund this support? These issues must be addressed when performance and capabilities assessments are part of an employee development effort.

- Assess participants' development needs and identify development activities for meeting those needs. Assess gaps between development needs and opportunities.[8]

- Specify work placement and assignment practices for matching employees with work that is aligned with their competencies and life-career preferences. Verify the legality of the practices before applying them.

- Announce formal implementation of start-up activities to participating employees and their supervisors. Explain the philosophy, foundation, and objectives of employee development; the approach that will be used to provide the services; employees' and supervisors' responsibilities; the benefits for employees and the organization and how they are related; and specific steps to be followed to implement the activities and the time frame for doing so. This should be a structured presentation that allows for extensive participation by employees and their supervisors.

- After the start-up process has been completed, implement the planned evaluation activities by collecting and analyzing summative evaluation data.[9] Prepare a comprehensive yet brief evaluation report and present it to the project sponsors, with recommendations for the long-term implementation of an appropriate employee development process.

Step 11: Brief senior managers on outcomes and lessons learned

Although each application has its own information requirements for senior management, the following key points should be covered:

- Review start-up process objectives and their relationship to the organization's strategic goals, business objectives, and competency needs.

- Highlight the purposes of both life-career and competency assessment, how each was completed, the results that were achieved, and the value of both to employees and the organization.

- Summarize the work completed to date.

- Identify successes and lessons learned.

- Document the impact of employee competency acquisitions that resulted directly from start-up activities.

- Provide case reports or testimonials of successes from participating employees and their managers.

- Cite unintended benefits or outcomes that were realized.

- Identify and give frank, specific reasons for process start-up objectives that were not achieved. Explore the issues with participating senior managers.

- Recommend institutionalizing a competency-based employee development process in the organization. List the resources and management support needed to create a continuous, strategically focused process that will benefit both the organization and its employees.

Step 12: Institutionalize and evaluate the employee development process

If senior leaders make the commitment to a formal, competency-based process, the successful start-up must be institutionalized, usually by extending the process to a wider audience, to greater depth with the existing audience, or both. At this stage, HR practitioners should confirm the following conditions:

- Key leaders agree on a clear philosophy and framework for a competency-based employee development process.

- The philosophy and framework are communicated throughout the organization.

- Adequate resources have been committed to institutionalize the process.

- A formal, continuous assessment mechanism is in place to track process accomplishments and identify areas for improvement.

Finally, how will evaluation be planned and conducted? Evaluation planning began earlier in this model and was included in Step 7, with the development of a start-up plan. HR practitioners should examine evaluation activities and their effectiveness and decide on any necessary modifications. We have found the CIPP (context, input, process, product) model by Stufflebeam to be a useful first resource for conceptualizing a systematic evaluation of this type of intervention.[10] The American Society for Training and Development also has available numerous evaluation resources. Return on investment should be researched and documentation made available to senior management. It is best to have an independent assessor perform comprehensive evaluations of a summative nature, when possible.

[3]For a more extensive discussion of DACUM, consult Dubois and Rothwell (2000).

[4]For descriptions of competency assessment procedures, consult Dubois and Rothwell (2000).

[5]For more on finding personal meaning and enjoyment in work, see Eanes, Richmond, and Link (2001); and Bloch and Richmond (1997, 1998). The stages of a life-career and the competencies that individuals must possess and use in appropriate ways for successful life-career plans are identified and discussed in Dubois (2000).

[6]Bolles (1981) includes a discussion for setting life-career priorities and presents a method for doing so. The instrument he recommends, the "Prioritizing Grid for 10 Items," is found in this work.

[8]For detailed information on competency-based individual development planning, including useful instruments, consult Dubois and Rothwell (2000).

[9]For extensive discussion on planning the process evaluation, see Stufflebeam (1974a, 1974b); and Stufflebeam et al. (1971).

[10]See Dubois (1993), pp. 227–231; Stufflebeam (1974a, 1974b); and Stufflebeam et al. (1971).

Employee Development and Succession Management

It is well worth noting that employee development plays a key role in many areas of HR management. Succession planning, for example, has become a major issue for organizations as workers from the baby boom generation are retiring or preparing to retire. Succession planning and management tend to be viewed largely from a top-down rather than a bottom-up perspective, but planning should be a priority at all levels of most organizations. Regardless of perspective, however, a competencybased process will make a substantial contribution to closing the succession-related gaps in an organization's competency pool. See Appendix D for a discussion on the interrelationship of the employee development, individual career management, and succession management processes.

Summary

In this chapter, we introduced the employee development concept from several perspectives. Because this complex area of human resources is often surrounded by confusion, we provided operational definitions of key terms. The chapter addressed ways of making employee development competency based and enumerated the advantages and challenges of competency-based practices. We explained organizational conditions that suggested the use of either a traditional or a competency-based approach. A model for creating and implementing a competency-based employee development process in an organization was presented and discussed in depth. Finally, we noted the value of a competency-based process in meeting the demands of succession management.

Part One - Finding A New Focus

Part Two - Understanding Competency-Based HR Management

- A Need for Implementing Competency-Based HR Management

- Competency-Based HR Planning

- Competency-Based Employee Recruitment and Selection

- Competency-Based Employee Training

- Competency-Based Performance Management

- Competency-Based Employee Rewards

- Competency-Based Employee Development

Part Three - Transitioning to Competency-Based HR Management

- The Transformation to Competency-Based HR Management

- Competency-Based HR Management The Next Steps

- Appendix A Frequently Asked Questions About Competency-Based HR Management

- Appendix B Further Suggestions on Employee Development

- Appendix C Examples of Life-Career Assessment Exercises

- Appendix D Employee Development and Succession Management

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 139