BASIC TRADING SKILLS

The four-step process for blueprinting negotiations is easy to remember, even if only because all it basically does is answer these two questions: “What are the consequences if we do not reach agreement?” and “What items are likely to be included if we do reach agreement?” At the same time, what Eric Fellman says about life in his book The Power Behind Positive Thinking (HarperCollins, 1997) can also be said of the process: “It’s simple, it’s just not easy.” In fact, in that respect our process avoids the failings of most negotiation training, which usually offers long lists of tactics and countertactics that are not only difficult to remember but may not mesh with your personal style as a negotiator. I don’t feel it’s either necessary or, for the matter, even advisable to tell you exactly what words to use for two good reasons. First, you probably wouldn’t be able to remember them, and, second, even if you could, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t use your own words.

A Rational Way of Responding to Tactics

It’s in this spirit that I’d like to offer you a process for responding to the other side’s tactics. Throughout the book I’ve shown you how to uncover and anticipate those tactics, but this skill—which improves with time—can be extremely helpful during the trading-tactical phase of a negotiation. The three steps of the process are:

-

Determine whether the tactic is unrealistic anchor related, single-issue trade related, or misdiagnosed CNA related.

-

Restate the tactic in terms of the Strategic Negotiation Process.

-

Use the skills of the process to respond appropriately.

These steps are based on the premise that virtually every tactic that comes from the other side can be traced back to anchors, trades, or CNA. Following are some examples to help you recognize the kinds of tactics you’re likely to encounter. (And remember they’re just examples and absolutely not meant to be memorized!)

Common Anchoring Tactics

-

“My budget is X.”

-

“Last year’s price was X.”

-

“I expect an X percent reduction off last year’s price.”

Common CNA Tactics

-

“Your competition is lower.”

-

“I can get the same thing better, faster, and cheaper.”

-

“As a supplier, you’re the most inflexible and difficult to deal with.”

Common Trading Tactics

-

“You need to sharpen your pencil.”

-

“Can you throw that in for free?”

-

“Give me a break on that item.”

Once you’ve figured out where any particular tactic is coming from, the next step is to put it into the language of the process. In our workshops, for example, when a participant tells a story that ends with something like “. . . anyway, after all that the customer had the audacity to tell me I had to sharpen my pencil,” we respond with “So you’re telling me the customer asked for a one-item concession.” Thinking through the tactic in this way, and categorizing it, enables you to be more objective and, as a result, less emotional in dealing with it.

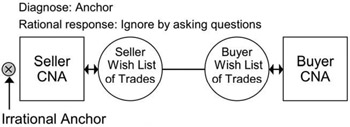

Of course, identifying the tactic and restating it so you can see it more objectively are important, but the next step—responding—is even more so. How do you do that? The best way of responding to an anchoring tactic is to simply ignore it. By ignore it I don’t mean that you pretend your customer didn’t say anything. What I mean is that you acknowledge hearing what they’ve said and then ask a question or two about other elements of the negotiation to get them off the subject.

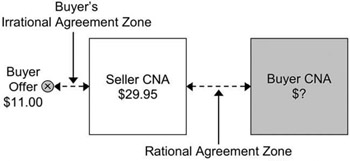

The one thing you should never do when responding to an anchoring tactic is to reanchor the negotiation. Let’s say, for example, that there’s a very high demand for your Gizmo (your CNA); you’re selling it for an average price of $29.95; and your customer tries to anchor the price at $11.00. If you respond by saying, “You’re crazy, I get at least $29.95 for my Gizmo,” what you’ve done is created an Agreement Zone that looks like this:

Because, on average, a deal like this will close somewhere around the middle of the Agreement Zone, or at about $20.00, if you reanchor at $29.95, you’ll wind up with nearly $10.00 less than your average market selling price. So, again, the best way to respond is by ignoring it and moving on.

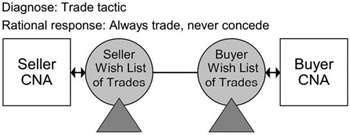

When a customer uses a trading tactic, all you have to do is remember the two rules I mentioned earlier: “Never concede—always trade” and “Never negotiate one thing by itself.” Even though, again, I can’t absolutely guarantee that this way of responding to tactics will work every time, doing it this way will substantially increase your chances of closing successfully.

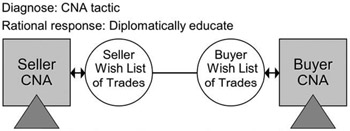

Finally, so far as CNA tactics are concerned, there are two ways of responding depending on the situation. If the client actually does have a better, faster, and/or cheaper value proposition as his Consequence of No Agreement, you should adjust your offer accordingly. On the other hand, if the client is bluffing or is mistaken about their CNA, the best course to follow is to diplomatically educate them by providing a rational analysis of the difference between the various alternatives.

Here are some examples of the frequently encountered tactics mentioned above, how they can be evaluated, and how you might respond to them. Again, I’m not suggesting that you use these particular words. These examples are provided just to give you an idea of what I’m talking about.

Buyer Tactic: “My budget is X.”

Evaluation: This is an anchor-related tactic, and it has nothing to do with your pricing.

Response: “I understand your concern about your budget, but how do the volume and length of contract issues we discussed compare in importance to pricing?”

Buyer Tactic: “You need to sharpen your pencil.”

Evaluation: This is a trading-related tactic in which your customer is trying to force you into a one-item concession Response: “I’d be happy to build an offer with a lower price. Can we talk about lengthening the contract or adding in one more product line?”

Buyer Tactic: “Your competition is lower.”

Evaluation: This is a CNA-related tactic in which the customer is saying that his CNA is better than your offer.

Response: “My competitor may be cheaper when you look at just the domestic element of the offer, but does it still look the same when you factor in the international element?”

Again, after looking at literally hundreds of tactics, we’ve found that virtually all of them fall into one of these three areas. And if you go back to what you know about anchoring, Wish Lists, and CNA, you’ll find that responding this way is quite easy and effective. You will also find that your response will be based on facts and analysis rather than on emotions.

Let’s do a quick test. Your customer says, “I’m overpaying compared to what you charge other customers in the market.” Is this primarily:

-

An unrealistic anchor?

-

A single-item concession request?

-

A misdiagnosed CNA?

The answer is (c) A misdiagnosed CNA. The client has assumed—incorrectly—that if you don’t reach agreement with him or her, you’ll sell your product to someone else at a lower price. The most appropriate way to respond to this would be to say something like: “Actually, that’s not true. Some of our customers do have lower prices, but we’re either not doing warehousing for them, which you said you wanted, or their volume is at least three times the size of what we’re talking about here.” In any case, as you can see, dividing all possible tactics into only three categories makes them much more manageable and much easier to respond to.

The Customer’s Ideal MEO

When the trading begins, one of the first things a customer is likely to ask for is the most complete MEO—the most expensive—at the price of the least complete—the least expensive. Lots of people have been taught that it never hurts to ask—which is usually true—so they figure the worst thing you can do is say no. Of course, that’s exactly what you should say. A very diplomatic way to say no without actually saying it is to say something like “Sure, we can find you a lower-priced option. We just need to adjust the offering a bit based on your needs.” Then you can move items in and out of the MEOs and rearrange the pricing until you’ve found a way that will satisfy both sides.

To do that it’s often helpful to ask the customer to rank the MEOs from one to three in order of their most to least desirable. Doing so accomplishes several purposes. First, you’re not asking for any commitment, so the customer doesn’t have to be defensive, but at the same time you are working together. Second, if there are multiple buying influences in the room, you can learn a lot from what they say among themselves as they discuss how to rank the offers. I was once in a meeting in which the seller was offering three MEOs for some factory automation software. When the buyer said he’d rank the lowest-priced offer the highest, the vice president of manufacturing literally jumped out of her chair and said, “I don’t care how little we pay for it; if it doesn’t work on the plant floor, we’ve paid too much for it.” The group quickly reranked the offers, and the option with lots of service and support moved up a notch. The third advantage of having your customer rank the MEOs is that, on the basis of the final ranking, you can determine what is most to least important to the customers. If, for example, they rank as lowest the option that has 24/7 support, and they rank as highest the one that guarantees install time, you get even more detail on their prioritized Wish List.

Repricing the Offer

Once you have a clear picture of your customer’s ideal MEO, you will probably need to reprice that offer. I strongly suggest that you do this separately from the group, either in a five-minute break or when you come back the next day. The reason for this is that the prices of MEOs are essentially based on the prices of their individual items, so if you have to recalculate the price, it’s easier—and better—for you to do it without your customer sitting there waiting. I also suggest that, to the greatest extent possible, you suggest a price for the entire package rather than for each individual item. If you price the items separately, your customer will probably ask for cost reductions on each one. And remember that you never want to negotiate any one item by itself.

You can, if necessary, break down the package into several component parts and suggest a price for each. For example, if you have nine or ten items in an MEO for a customer who’s pushing you on line-item pricing, you might be able to break all the items into three categories— such as design of the solution, delivery of the solution, and ongoing maintenance—and provide prices for each. Doing so can help you avoid even being put into a situation in which you can be asked to negotiate on one item.

Let’s say, for example, that you’ve made a very low-priced offer in which you’ve done everything you can to trade risk back to the customer, including eliminating free service that detracts from your own profits. Now, though, the customer comes to you and asks that you put the service back in because your competitor offers free service. How do you counter such a request? It’s difficult, to say the least. For one thing, you don’t know all the variables of the deal your competitor offered. They may, for example, be offering free service but at a much higher overall price and/or with larger volume commitments. Because of that, unless your customer is willing to show you everything that your competitor has offered, which is certainly not likely to happen, you can’t do an “apples-to-apples” comparison. It may be, too, that your product or service is simply better than your competitor’s (the customer’s CNA) and you don’t offer free service because it’s rarely needed. The point here is that it’s best if you can avoid being put into this kind of situation in the first place.

One of our selling clients dealt with this type of situation in a very interesting way. They were selling software to one of the largest chip manufacturers in the world, and the customer kept going back to the MEO and asking for concessions on individual aspects of the multiple trades that were part of the offer. Our client tried to explain that the entire deal was a package, but the customer just didn’t seem to understand. After several fruitless attempts at explaining, the seller finally said, “Look, I’m trying to achieve X percent gross margin here. I’m willing to move on as many items as you want, but you have to understand that if I do, I’ll have to adjust something else to achieve that margin.” That got through to the buyer, and they then proceeded to work together to devise trades that the buyer was comfortable with and, at the same time, provided the seller with the gross margin they were looking for.

Responding to Outrageous Demands

Finally, it’s important for you to bear in mind that just because a customer asks for something doesn’t mean you have to respond. Buyers sometimes make truly outrageous demands, but that’s no reason for you to go back to headquarters to ask for whatever it is they’re demanding. The important thing to remember, regardless of how outrageous the request may be, is to not get emotional about it. What you should do, instead, is simply ask for a trade in return. Eventually, your customer will begin to understand that trading is good for both sides, and that they’re likely to get more of what they want if they’re willing to trade with you. The number of margin-reducing concessions two people can make may be small, but the number of value-creating trades they can make is limited only by time and their creativity.

So now you’ve constructed three custom MEOs, presented overviews of them to your customer, provided details on each, had the customer rank them in order of preference, traded some items in and out of the highest-ranked MEO, and changed the pricing a bit. What you’ve done here, whether you realize it or not, is create and divide value. Trading, which is the cooperative aspect of the process, is what enabled you to create value by essentially putting more money into the deal. And claiming that value, which is the competitive aspect, is what enabled you to divide that money. More often than not, by the time a deal is closed, the buyers have won a few and the sellers have won a few. But the important point here is that by using the Strategic Negotiation Process to blueprint negotiations, both sides come out of the deal better than they anticipated when they went into it. They’ve not only achieved a “win-win” situation; they’ve gone beyond it.

My experience suggests that there are essentially three types of negotiators. The first is the “tough” negotiator, the type who closes a large percentage of his or her deals, but the deals tend to be small because they leave value-creating trades on the table. The second type is the “nice” or “easy” negotiator, the type who tends to trade well and close a lot of deals but gives up too much of the joint value to the other side. The third type is what I call the “rational” negotiator, and that’s what you should be. This is the type who is strong in the cooperative aspect that will increase the likelihood of closure and creating true value but is also strong in the competitive aspect, claiming as much value as possible without hurting the relationship.

This raises the question of what’s “fair” in terms of dividing the pie. Many people think of 50-50 as fair. Although there’s a certain logic to that, the problem with it is that you’re usually splitting 50-50 of a completely arbitrary number! Let’s say that what you’re selling has a market value of $100; the customer offers an arbitrary $50 and then says, “Let’s split the difference and agree on $75.” It’s certainly a very easy way to settle a deal, but there’s nothing particularly fair about it. Nor, obviously, is it something you’d want to do.

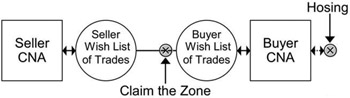

You’ve achieved fairness in a negotiation any time you can claim as much of the created joint value as possible without forcing the other side to take a deal that’s worse than their CNA. Leaving your customer with something less than their CNA is what I call “hosing” the other side, and it’s typically neither a good thing to do in ongoing relationships nor a good message to send to the market. As I mentioned earlier, what you want to do is claim as much of that zone as possible by anchoring only marginally better than the other side’s CNA. If you anchor far better than the other side’s CNA to be “fair,” you’ll be giving up too much value. And if you anchor marginally better than your own CNA, you’re likely to leave money on the table. But if you anchor marginally better than the other side’s CNA, you’ll be able to claim most of the value and still give the other side a win by exceeding their CNA plus the extra value you created by trading.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 74