THE CONSEQUENCES OF NO AGREEMENT ESTIMATION

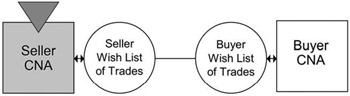

The purpose of the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation is to enable you to determine who has the power in the negotiation and the location of the Agreement Zone, the place where both sides prefer agreement to impasse. Doing this essentially requires you to answer three questions for both sides in the negotiation:

-

What are the possible Consequences of No Agreement and which is the most likely?

-

What are the elements of those Consequences of No Agreement that need to be considered?

-

Are those elements hard or soft costs or benefits in the short term and in the long term?

What are the possible Consequences of No Agreement and which is the most likely? As the seller, of course, your most likely Consequence of No Agreement is to lose the sale. The buyer, on the other hand, generally has three possible Consequences of No Agreement: going to one of your competitors, building the solution itself, or doing nothing. There are, of course, other possible alternatives, but analyzing every one of them is neither feasible nor necessary. In fact, ultimately, at the most basic level, every possible Consequence of No Agreement falls into one of these alternatives. Your decision about which is most likely will be based on your knowledge of the industry, the customer, and the competition.

What are the elements of those Consequences of No Agreement that need to be considered? The elements of each Consequence of No Agreement are those things that will be affected if you don’t make a deal and that you and your customer should accordingly take into consideration. Of course, because the same Consequence of No Agreement will have a different effect on the buyer than on the seller, the elements you consider will depend on which side of the table you’re on. Let’s say, for example, that, as the seller, your Consequence of No Agreement is to lose the sale. In that case, the elements of that Consequence of No Agreement—the things it will affect and that you should consider— would include the following:

-

How much revenue this customer represents

-

How losing the sale will have an impact on your bonus

-

How easy/difficult it will be to replace the customer

-

If any internal political ramifications result if you lose this business

Let’s say, on the other hand, that you are estimating your customer’s Consequences of No Agreement and have determined that the most likely one is for her to choose another supplier. What you need to do, then, is think about how making that decision will affect her—that is, what elements should she be taking into account in comparing you with your competitor. Assuming you are the incumbent, the elements she should be considering would include these:

-

How much it will cost the customer to switch from you to your competitor

-

How the competitor’s product quality compares with yours

-

How the competitor’s service quality compares with yours

Are those elements hard or soft costs or benefits in the short term and in the long term? Once you’ve determined the Consequences of No Agreement and the elements associated with those consequences, the next step is to determine whether those elements are minuses or pluses (costs or benefits) and whether they are hard or soft costs or benefits. Hard costs or benefits include anything that’s quantitative or measurable— that is, something that can be given a dollar amount, such as increased revenues, training costs, percentages, time, output, or the development of a new product pipeline. Soft costs and benefits, on the other hand, are qualitative and include those things to which it is difficult to attach a metric. These might include political ramifications, risk for the seller, customer satisfaction, ease of use of the product or service by the buyer, or ease of working with the buyer for the seller.

As you can see, many types of elements—whether they are ultimately minuses or pluses—cross industry lines. Things like customer satisfaction, for example, are elements of a customer’s Consequences of No Agreement in almost every negotiation, regardless of the business. However, what constitutes short term and long term, and the significance of the difference between them, can vary considerably from one industry to another. For example, one of our clients is a major steel producer that makes, among other things, steel pillars for building construction. During negotiations over a deal with one of its customers, a construction company, the customer told our client it was thinking of using concrete instead of steel for its pillars, as concrete was less expensive. In other words, the customer’s Consequence of No Agreement was concrete, and the only element being considered was price.

Our client had to admit that in the short term at their then-current prices, concrete did cost less than steel. Because we had conducted a Consequences of No Agreement Estimation for our client, however, the client was also able to point out that even though the lower price of concrete was a short-term benefit, the “total cost of ownership” in the long term would actually be less for steel because concrete may cost more to maintain and may not last as long as steel. This is just one example of how the difference between short term and long term can have an impact on a specific industry. No doubt you can think of others that are specific to your own business.

Your Side’s Consequences of No Agreement

You begin with your own Consequences of No Agreement—the seller’s—because it’s the simplest. As already noted, the most common Consequence of No Agreement for the seller is to lose the business. But because every negotiation is unique, the effects of that Consequence of No Agreement, that is, the real meaning of “lose the business,” changes from one negotiation to another. For that reason, unless you do an estimation of your own Consequences of No Agreement as well as that of your customer, there’s no way you can tell exactly what impact it will have on where the power lies or on the location of the Agreement Zone.

Let’s say, for example, that you’re in the middle of negotiations over a deal, and your customer is being so tough that you’re not sure you’ll be able to come to an agreement. At the moment, though, the economy is exploding, you’ve been Salesperson of the Year for the past three years, you’re at 176 percent of your annual goal, and it’s only the third quarter. Obviously, although you would of course prefer to not lose the sale, it would hardly mean the end of the world. But what if the economy were in recession, you were only at 65 percent of your sales goal, it was coming down to the end of the fourth quarter, and your job was on the line? Clearly, then, losing the sale would mean something else entirely. The point is that unless you do the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation, you have no way of knowing what your true costs and benefits might be. If you’re still not convinced, though, the following story might change your mind.

My partner, Max Bazerman, tells a story beginning with his phone ringing one Sunday night. It’s one of his distant cousins, who is in the market for a house. The cousin and his wife have been out looking at houses all day, and they’ve found one they think is perfect. After providing Max with an excruciatingly lengthy and detailed description of the house, the cousin finally gets to the point. “They’ve got it listed at $185,000,” he tells Max. “We offered $165,000, and they countered with $179,000. What should we do?” Being the expert in negotiation that he is, Max asks, “What will happen if you don’t buy the house?” For a moment there is silence on the other end of the phone. And then his cousin replies, somewhat frustrated, “I didn’t call you for advice on how not to buy a house.”

So Max asks the same question again. This time the cousin says, “You don’t understand. The next best house has an avocado green 1970’s kitchen and it’s the same price.” But questioning the cousin further, Max discovers that other than the green kitchen, the second house is just as “perfect” as the one they’ve fallen in love with. Max asks his cousin if it might be possible to get that house for $20,000 less, which would provide them with enough money to remodel the kitchen. The cousin thinks this is a good possibility and decides to go back to the second house’s owners to discuss it. Max gratefully goes back to what he was doing when the phone rang.

Max’s cousin had gone into the negotiation without having thoroughly analyzed his own Consequences of No Agreement and was convinced that the consequences of not buying the first house were horrible. In fact, Max’s cousin did the same thing that most of us do—focus on our own consequences and assume they’re much worse than they actually are. On that basis, he also concluded that he had no power in the negotiation. But when Max helped him do the analysis, he recognized that the consequences were not necessarily as bad as he’d anticipated. In other words, Max’s cousin was able to change his Consequences of No Agreement for the better and in the process substantially increase his power. Of course, Max’s cousin was the buyer in this situation, and we are more concerned here with your Consequences of No Agreement as a seller. But the principle applies regardless of which side of the table you’re on.

We recently saw a similar dynamic at work during a client meeting with the major account executive of a U.S-based semiconductor industry supplier. This company was one of the largest in the industry, selling tools and software priced in the $50 million to $300 million range. One of our new consultants, Sam Tepper, a very bright Ph.D. from Northwestern University, was taking the lead in the meeting and asking Consequences of No Agreement–related questions. The account executive just kept shaking her head. “You don’t understand,” she said. “Our closest competitor is larger, has a more complete solution, and has tools that are more accurate and more reliable. Plus, they’re often willing to give those tools away as part of a large deal.” What she was telling us was that the buyer had a great Consequence of No Agreement—numerous benefits and virtually no costs—while their own Consequence of No Agreement was to lose the business—which had no benefits and lots of costs.

I had no idea how we might respond to this comment; it seemed like an impossible situation. Sam, however, knew exactly what to say. “My gosh,” he exclaimed, “how are you still in business?” The executive seemed stunned by the question. At last, though, she admitted, albeit rather sheepishly, that the company had grown more than 40 percent over the previous year. And, in fact, after we did a Consequences of No Agreement Estimation with them, we found that not only was our client’s Consequences of No Agreement better than they thought, but also that their customer’s Consequence of No Agreement—choosing a competitor— would actually present them with several costs. We’ve seen time and time again how sellers can overestimate the impact or effect of their Consequences of No Agreement and underestimate the costs to the other side. That’s why it’s so important to do the analysis.

Estimating your side’s costs and benefits. Having decided that, as the seller, your most likely Consequence of No Agreement is to lose the business, the next step is to determine the elements of that Consequence of No Agreement, that is, the effects it will have, and decide if those elements are hard or soft costs or benefits for the short term and long term. For you as the seller, these elements are essentially those that will have an impact on you, your company, and/or your industry. These might include, for example, sales revenues, sales profits, and your personal financial stake (e.g., a bonus), all of which are hard costs or benefits. They might also include company-related political ramifications, such as your boss’s friendship with the customer’s executive vice president; industry-related political ramifications, like the message it sends to the market if you win or lose a big customer; and long-term customer relations, all of which are soft costs or benefits. Here’s an example of some of the kinds of costs and benefits that might result when a seller loses a sale:

| The Seller’s Consequence of No Agreement: Losing the Sale | |

|---|---|

| Elements to Be Considered | Cost/Benefit |

| $100,000 in revenue; costs of sale; my bonus | Hard Cost |

| My boss will not be happy; competitors will get my customer | Soft Cost |

| Market price is 4 percent higher than the client is willing to pay | Hard Benefit |

| The client’s toughness on our operations team | Soft Benefit |

Gathering and recording data. Now it’s time for you to determine the elements of your own Consequence of No Agreement—losing the business—as well as determining whether the elements are costs or benefits in your own negotiation. As you begin to gather data on these costs and benefits, you should bear in mind several things.

The first is the importance of being objective. You don’t have to like what you say here, but it should be as true, or at least as close to the truth, as you can make it. If at this point you knowingly estimate your own Consequences of No Agreement to be greater—or less—than they are, you will be constructing a picture of the situation that’s unrealistic and, ultimately, of little use. The first step in becoming a world-class negotiator is arming yourself with facts, not assumptions, and only by being brutally honest will you be able to do that.

Second, in gathering data it’s very important for you to concentrate on the specifics of this negotiation. Consequences of No Agreement are not something that exists at the market level; they’re specific to the particular deal. For that reason, it’s essential that in conducting the analysis you bear in mind what customer this is; which competitor or competitors may be involved; what product or service you’re offering; the time of year; your current financial condition; whether you are the incumbent; the current market, pricing, and demand for your product or service; and any emerging competitors. Only by concentrating on this specific negotiation will you be able to construct an accurate picture of the situation.

Finally, although as a seller it’s not difficult to determine what costs there might be in losing a sale, it’s much more difficult to determine what benefits there might be. Our experience suggests that basically only two kinds of benefits are possible to the seller in such a situation, both of which are included in the table above. The first is that if this particular customer has been pushing you hard on price, the chances are you’ll be able to replace him or her with a higher-margin customer. The second is that if this is a “high-maintenance” customer—one who has required a lot of time and effort for you to deal with—you may well be better off without him or her.

To help you remember the hard and soft costs and benefits in the short term and long term, we’ve found it helpful to record them in the format on page 54. As you’ll see, we’ve provided space for six types of data. The first concerns your Consequences of No Agreement. Again, this is supposed to be a simple, straightforward answer to the question “What will happen to us if we don’t make the deal?” As I’ve already noted, the answer to this question is most likely to be “Lose the sale” when you’re the seller.

The second, third, fourth, and fifth areas are, respectively, where you record the short-term and long-term hard costs, soft costs, hard benefits, and soft benefits associated with that Consequence of No Agreement. If you have any questions about the differences between these costs and benefits, you can turn back to the section in this chapter in which I discussed them.

The sixth and final section may be the most important one of all. It’s there that you record whatever additional information you feel you still need about your costs and benefits. You don’t have to concern yourself at this point with where you will get that information; you’ll learn that during a later step in the process. For the moment all you have to do is list the data that is needed. (Note, incidentally, that you will find a copy of this—as well as all of the book’s other forms—in the Appendix.)

The Other Side’s Consequences of No Agreement

Now that you’ve determined your own Consequence of No Agreement along with the costs and benefits associated with it, it’s time for you to estimate your customer’s. We very often hear people say that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to know the consequences for the other side. And given the fact that most people don’t think much about what it might mean to their customer to lose the deal, it’s not particularly surprising that they should feel that way. The fact is, though, that, as already noted, your customer really has only three likely Consequences of No Agreement: (1) go to a competitor, (2) build the solution themselves, or (3) do nothing.

Going to a competitor is the most frequent Consequence of No Agreement for a buyer. This is because, as you know, buyers are almost always convinced that they can get it better, faster, cheaper elsewhere, regardless of what it is, and whether or not it’s true. But, as you also know, it’s never that simple except in the case of true commodities, of which there are very few. There are always other variables that should be taken into consideration. Doing so, that is, using what you’ve learned about their needs during the sales and negotiation processes to determine the true costs and benefits of going to one of your competitors versus buying from you, you’ll be able to show them why it’s in their best interests to buy from you based on all the relevant factors, not just price.

Building a solution themselves is probably the next most frequent buyers’ Consequence of No Agreement. It’s quite common for a customer to believe that its in-house people can build the same solution as yours, custom-made and for less. Sometimes, in fact, it’s true. If it is, though, there’s something fundamentally wrong with your value proposition. Even though buyers believe they can do it better themselves, more often they can’t. And the best way of making them understand that is to compare the actual costs and benefits of their doing it themselves versus hiring you to do it.

Despite what I’ve called it, doing nothing, the third most likely Consequence of No Agreement, isn’t really doing nothing at all. In fact, what it really means is the buyer’s taking the resources he or she would have expended on your offer and using them elsewhere. Let’s say, for example, that you have a customer who has earmarked $100,000 for a consulting project. You present them with a $100,000 consulting solution, but they come back and say that they’ve decided not to do anything at this time. Although it may be true that the customer isn’t doing anything “externally” with those budget dollars, it may be putting them toward an entirely different project, such as hiring a new salesperson, which is, then, the customer’s Consequence of No Agreement. Under those circumstances, your challenge is to compare the costs and benefits of their hiring a new salesperson versus your consulting solution.

Although these three different Consequences of No Agreement may have different costs and benefits associated with them, it’s important to bear in mind that regardless of which Consequence of No Agreement is most applicable in any particular situation, it is essentially always a matter of you versus some form of competition. That competition may be another company, the customer doing it himself or herself, or the customer using the budget allocated for your product or service for some other purpose. Remember, too, that your customer will make a decision based on a perception—probably inaccurate—of whether what you have to offer will be a benefit to him or her. For that reason, the best way to prepare yourself for any of these situations is to determine as many costs and benefits associated with both sides’ Consequences of No Agreement as you can.

Finally, you may find yourself in a situation in which more than one of these three possible Consequences of No Agreement seems to be appropriate. In that case, for the purposes of the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation, you should select the one that you think is most likely to occur, regardless of which one it might be.

Estimating the other side’s costs and benefits. Having decided which of the three possible Consequences of No Agreement is most likely for the other side, the next step is to determine the elements of that consequence and estimate whether they are hard or soft costs or benefits for the short term and long term. For the buyer, the most important of those elements are (1) the prework or design stage, (2) the installation phase, (3) ongoing operations and management, and (4) output, that is, the extent to which the product or service fulfills the business purposes for which the buyer purchased it.

Examples of costs and benefits in the prework or design stage might be ease or difficulty of customization, expense of customization, or the amount of knowledge or experience possessed by the people who are designing the product or service. Costs and benefits in the installation phase might include the ease or difficulty of integrating the product or service into an existing system, training costs, and switching costs (i.e., any expenditure the buyer might have to make as a result of purchasing from a new rather than an incumbent supplier). Among the costs and benefits in ongoing operations and management are ease of use, reliability, and service. Finally, for costs and benefits in the output stage, you might consider whether the product or service results in greater sales, reduced cycle time, fewer errors, or increased capacity. If you consider all these elements, it quickly becomes clear that when a buyer says “It’s cheaper elsewhere,” all he’s done is an incomplete and oversimplified analysis of his Consequences of No Agreement.

Here is an example of the costs and benefits that might result from the most frequent buyers’ Consequence of No Agreement: going to a competitor. Remember, this is supposed to be from your customer’s perspective, so to do this appropriately you have to put yourself in the customer’s shoes. Note here that incumbency plays a large part in the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation, and for this example I’m assuming that you are the incumbent.

| The Buyer’s Consequence of No Agreement: Going to a Competitor | |

|---|---|

| Elements to Be Considered | Cost/Benefit |

| Higher long-term maintenance; higher switching costs; lower output | Hard Cost |

| Hassle of retraining staff | Soft Cost |

| Competitor’s price is 9 percent lower in the short term | Hard Benefit |

| Will be a more important client to my competitor than he or she is to me | Soft Benefit |

Gathering and recording data. Now that you have an idea of how to determine a typical buyer’s Consequence of No Agreement and its effects, it’s time for you to determine the Consequence of No Agreement for the buyer in your own negotiation. As you gather data on your customer’s Consequence of No Agreement and the costs and benefits associated with it, there are several things you should bear in mind.

First, just as it was important to be objective in estimating your own Consequence of No Agreement and its costs and benefits, it’s extremely important that you do so in estimating your customer’s. As I mentioned earlier, it’s not at all unusual for sellers to overestimate the negative effect of their own Consequence of No Agreement and underestimate that of the people on the other side. But if you do that, you’re going to create an unrealistic picture of the situation that won’t do either you or your customer any good. That’s why it’s important that you be as honest and objective as you can.

Second, as was also the case with estimating your own Consequence of No Agreement, it’s essential in this step that you concentrate on the specifics of this negotiation. Every negotiation is different, so in estimating the Consequences of No Agreement and the costs and benefits of any particular negotiation, it’s important that you bear in mind what customer this is; which competitor or competitors may be involved; what product or service you’re offering; the time of year; your current financial condition; whether you are the incumbent; the current market, pricing, and demand for your product or service; and any emerging competitors. Only by doing so will you be able to construct a clear and accurate picture of the situation.

Finally, it’s important to bear in mind that what you are doing in this step of the process is making estimates—essentially educated guesses, based on what you’ve learned from past deals and from the sales process, about your customer’s business and industry. At this point you cannot, nor are you expected to, know with certainty what the other side’s Consequence of No Agreement will actually be. Later on I show you how to gather information from others in your own organization, as well as from outside sources, to validate the estimates you are making here.

Once you’ve gathered the information you need to determine the other side’s Consequences of No Agreement and its short-term and long-term effects, it’s advantageous to record that information in the format shown on page 59.

Now that you’ve analyzed and recorded the Consequences of No Agreement and costs and benefits associated with those consequences for both sides in your own negotiation, it’s time to put them together so you can apply them. As promised in the beginning of the chapter, having gathered this information you will now be able to answer the two questions that will enable you to take your first step toward becoming a world-class negotiator: “Who has the power in the negotiation?” and “Where is the Agreement Zone?” Just to give you an idea of how it’s done, here are the two lists of costs and benefits I used for the sample negotiation.

| The Seller’s Consequence of No Agreement: Losing the Sale | |

|---|---|

| Elements to Be Considered | Cost/Benefit |

| $100,000 in revenue; costs of sale; my bonus | Hard Cost |

| My boss will not be happy; competitors will get my customer | Soft Cost |

| Market price is 4 percent higher than the client is willing to pay | Hard Benefit |

| The client was very tough on our operations team | Soft Benefit |

| The Buyer’s Consequence of No Agreement: Going to a Competitor | |

| Elements to Be Considered | Cost/Benefit |

| Higher long-term maintenance; higher switching costs; lower output | Hard Cost |

| Hassle of retraining staff | Soft Cost |

| Competitor’s price is 9 percent lower in the short term | Hard Benefit |

| Will be a more important client to my competitor than he or she is to me | Soft Benefit |

Determining Who Has the Power

Now let’s look again at the first of the two questions: Who has the power in the negotiation? Determining the answer to this question is important because it affects how both sides think of the negotiation and, as a result, how they behave. Those who think they have more power in the negotiation tend to overestimate the value of their offer. As a result, they’re more likely to play hardball in the negotiation and are less willing to consider making trades. And when either side is unwilling to make trades, it makes creating value difficult for both sides and increases the likelihood of impasse. On the other hand, those who think they have less power are likely to underestimate the value of their offer, are likely to roll over too easily, and, in the process, unnecessarily give up value to the other side.

Interestingly, our experience has taught us that both sellers and buyers are likely to misdiagnose who has the power. They both tend to think that the other side has more power in any given situation. For example, a seller we worked with recently told us that a customer had them “over a barrel” in a negotiation. The seller was providing data services to a major telecom company and had been told by the buyer that, although they had been the only seller in the market, there were now two other suppliers with exactly the same data. In fact, one of those competitors had offered to not only discount their fees by almost 50 percent but also to pay both the cost of taking the existing data out of the customer’s organization and the cost of switching suppliers.

In the meantime, the seller’s account manager was being pushed on her sales goals for the year and was afraid that her job might be in jeopardy if she lost this high-visibility account. In other words, her Consequences of No Agreement weren’t very good. She felt, understandably, that the customer had all the power in this negotiation and that she could lose the sale if she didn’t concede. If she gave in, she reasoned, at least her company would retain the business, even if at a much lower margin.

When we completed the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation for both sides in this situation, however, we realized several things. First, the data the competitor was offering the telecom company wasn’t actually the same as our client’s data. When we compared our client’s data with its competitor’s, we found that the competitor could provide only domestic data, while our client had been providing global data. We also found that the buyer had just invested in a quarter-million-dollar system to integrate the existing supplier’s data into several key global databases, a system that would be rendered useless if the existing supplier were replaced. Finally, we recognized that taking the client’s data out of the buyer’s system—which the competitor had promised to do—would be a large, complex, and very expensive task. Although it was possible that the new supplier might have been able to assume some of the cost, it would be unrealistic to believe they could—or would—pay for all of it.

In other words, we were able to show that the buyer had not done complete due diligence, had only a verbal offer from our client’s competitor, and was misinformed about that competitor’s capabilities. Adding to this the potential risks of using a new, unproven supplier, the question of how much of the switching costs the supplier would actually cover and the new system the buyer had just installed, it became clear that our client had considerably more power in the negotiation than they thought they did.

On the other hand, we recently worked with a buyer—a major U.S. airline—who told us that the seller had it “over a barrel” in a negotiation. The airline was in the process of renewing its deal with a ground services provider in a very popular European destination. But it was frustrated by the fact that the provider was owned by the government and there were no alternative suppliers. The seller told the airline that “plenty of other carriers were willing to accept your gates” and they’d either have to agree to the supplier’s terms or pull out of the market, which would then be the airline’s Consequence of No Agreement. The airline felt it couldn’t afford to lose this critical vacation and business destination, so the airline’s buyer had been told to get the deal done. Their thinking was that even if their costs went up 30 or even 40 percent— hundreds of thousands of dollars—it would still be less than the millions they would lose if they accepted their Consequence of No Agreement and pulled out of the market. They felt, in other words, that they had no choice but to agree to the seller’s terms.

Again, however, when we did the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation for both sides in the negotiation, we found that the situation was not actually what it appeared to be. For one thing, although not reaching an agreement could very seriously damage the airline, it would be almost equally devastating for the city. This particular city relied on the airline for a major portion of both its tourists and business travelers. If the airline pulled out, even if it was replaced by another major airline, tourists who wanted to use frequent-flyer miles to get there would be greatly inconvenienced and might well choose other destinations. So too might people who preferred using this airline to get to the city but would be unable to because the airline no longer flew there.

Fewer tourists and business travelers would, in turn, mean the loss of jobs, which would create problems with the airport workers’ unions as well as incur political ramifications for the city’s leaders. In addition, although the city said other carriers were interested in filling our client’s gates, in reality, making such arrangements would be both time consuming and costly. In other words, even though the buyer felt that the seller had all the power in the negotiation, that wasn’t really true.

As you can see from these scenarios, both buyers and sellers can be mistaken in believing that the other side has all the power in a negotiation. Conducting the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation enables you to determine what it would mean to both sides if no agreement is reached and provides you with an understanding of the power you have as well as the power your customer has. Had both the buyer and seller in these examples conducted their own Consequences of No Agreement Estimation for both sides, they would have recognized they both had at least some power in the negotiation—and usually more than they had initially thought.

So who has more power in your own negotiation situation, you or the other side? All the information you’ve developed and recorded may have made it clear that you have much more power than you thought you did. If that’s the case, then doing the estimation will clearly have benefited you by enabling you to negotiate from a position of strength.

Conversely, the estimation may have shown that you don’t have as much power as you believed. In that case, you will still have benefited from it because it will have allowed you to see and recognize your limitations. At the same time, it will enable you to determine if there is anything you can do about the situation. When my partner Max’s cousin thoroughly analyzed his own Consequences of No Agreement while negotiating to buy a house, he recognized that the consequences were not necessarily what he’d anticipated, and he was able to change his Consequences of No Agreement for the better.

Max and I found ourselves in a similar situation when we first started our firm. In those days it was just Max, me, the dog, and the kitchen table. We had one lead—a major U.S. insurance company—and knew that if we lost the business (our Consequence of No Agreement), we could be in financial trouble because we had no other customers (the effect of our Consequence of No Agreement). Naturally, we recognized while we were negotiating with this firm that we had very little power. But having recognized that, we were able to do something about it. We began spending more time prospecting for additional customers, which not only enabled us to make money but, even more important, make our Consequences of No Agreement a bit better, and thus increase our power in negotiations.

Whether you’ve determined that you have more power than you thought or that your customer does, it’s advantageous to record what you believe to be true:

Based on my preliminary Consequences of No Agreement Estimation of this negotiation, I believe:

-

I have more power. ___________

-

The other side has more power. ___________

-

I still don’t know. ___________

Finding the Agreement Zone

As noted earlier, conducting a Consequences of No Agreement Estimation enables you to determine both who has the power in the negotiation and the place where both sides prefer agreement to impasse. Now that you’ve learned more about whether it’s you or the other side that has more power in your own negotiating situation, giving you a clear picture of who stands where, it’s time to figure out where you and those on the other side can meet: the Agreement Zone.

The concept of an Agreement Zone comes from the pioneering work of Roger Fisher and William L. Ury in their 1981 book Getting to Yes, which first advanced the idea of “win-win” as a negotiating strategy. “Win-win” was a substantial improvement over the old school of thinking about negotiation, which might have been described as “I win–you lose,” or vice versa. Fisher and Ury made it clear that the only time you reach a good business agreement (“win-win”) is when both sides are in positions in which they are better off than they would have been if they hadn’t agreed. This position, or place, is the Agreement Zone, or, as one of our clients from Japan calls it, the “sweet spot.”

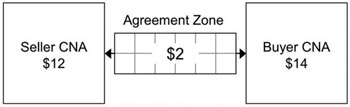

But what exactly is this sweet spot, and how do you find it? Here’s a simple example. A company has a product that’s been selling very well at an average market price of $12 per unit. The company has a customer in the same town that wants to buy the product. The customer can, however, get the product from another supplier for $11, which is then the customer’s—oversimplified—Consequence of No Agreement. But because the other supplier is in another town, the customer would also have to pay for shipping at $3 per unit. The buyer’s true Consequence of No Agreement, then, is $14, and the seller’s is $12. The Agreement Zone, or sweet spot, is $2. So as long as the buyer is willing to pay at least $12 for the product, the seller’s Consequence of No Agreement, and the seller is willing to accept less than $14, the buyer’s Consequence of No Agreement, both sides come out better than they would if they hadn’t made the deal.

This example also demonstrates that you should accept any offer, even if you don’t like it, so long as it’s better than your Consequence of No Agreement. Let’s say, for example, that I tell you I’m going to give you and your best friend $100. Your friend will be able to decide how to divide the money between you, but you both have to agree on that distribution before I hand it over. The easy solution would be to share the money evenly because that’s “fair.” But what if, instead, your friend wants to keep $95 for herself and give you $5? How likely are you to take that deal? Most likely, you’ll decline. But is that really the best strategy? If you refuse the deal, you get the Consequence of No Agreement—zero dollars. If you accept, you get $5, which is clearly better than your Consequence of No Agreement.

The point here is that in trying to find the Agreement Zone, it’s important for you to remember that you are not in competition with your customer. Your customer’s success has little to do with your evaluation of the deal. Even if the customer is going to come away from this particular negotiation with gobs of money, you should take the deal as long as you can do better than your Consequence of No Agreement. The only real issue, then, is exactly what your Consequence of No Agreement is. And as you’ve now seen, you can only determine that through the Consequences of No Agreement Estimation you’ve just conducted. More important, though, as you will see in the following chapters, is that you will actually be able to enlarge the Agreement Zone by conducting this kind of analysis. In other words, you’ll actually be able to grow that sweet spot from $2 to $3, $4, or even $5 so that both you and your customer will be able to come away with a better deal than either of you could have anticipated going into it.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 74