5.6 The New Structure of Business

5.6 The New Structure of Business

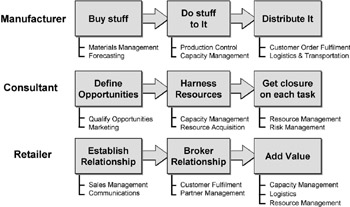

Businesses are often founded on a simple premise, that is, the development of a product or service that represents a desire in a consumer group or opportunity created by a change in the business environment. A founder – or founding team – decides to bring a capability to the market and establishes an optimum process for fulfilling customers’ orders for a product or a service. The founders create a value proposition for the business and carefully construct the optimum process or what is called a ‘normative business model’ for fulfilling the demand. All companies begin with a normative business model and strive through a series of organizational growth cycles to achieve the optimum operating state. This optimization occurs within the firm in two ways. Firstly, by continually streamlining business process steps and applying technology to achieve greater productivity in each step and secondly, by optimizing the intersections between the company’s internal processes and its external, transaction-based processes with suppliers and distributors. One could argue that the ultimate optimization of business in the later stages of an organization’s maturity is to establish control of a product from raw material to final distribution to customers, perhaps more clearly described as a monopoly or having monopolistic traits. Different types of business organize and address the process of adding value in various ways, often emphasizing the uniqueness of their process components, but these can be simplified into three prime functions, depicted in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2: Business process activities

Over time, people are added to the founding group and typically a hierarchical structure of organization emerges. Bushe and Shani remind us that:

Structure is the division and coordination of labor. Organizations exist because there is something to do that requires more than one person; therefore, the work is divided up among several employees. Once the work is divided up, some way has to be found to coordinate the efforts of these individuals to ensure that the final product or service comes together. Structures are environments that affect how people behave. They channel effort and energy in a particular direction. When they are well designed, they support employees in accomplishing their tasks; when they are poorly designed, they can get in the way. Since they channel effort, changes in structure can lead to changes in how people behave at work.[155]

Coping with Changing Business Events

Business events invariably occur, such as customers requesting split deliveries of a single product in the order or fulfilment process which was not anticipated by the original business process. This triggers an exceptional state and the organization ultimately develops a method to address the anomaly. Organizations that reach this level of business maturity remedy this situation either by incorporating the rules and solutions for the exception into the business process, or else developing an external process that deals specifically with the exception. In the latter, the preservation of the normative model is the desired goal, and the exceptions are not only corrected but also evaluated, feeding back information on the root causes of the problem to the appropriate group within the organization. For example, a product that is continually rejected by a customer may have a design flaw which the research and development group takes action to correct, instead of creating a new department to rework rejected products. Exceptions and modifications coming from customer input and changes in the business environment ultimately lead to alterations to a firm’s business process, as noted by Tushman et al.:

As competitive conditions change, fundamentally different organization forms are required. However, due to organization inertia, many organizations either do not effectively attend to environmental change or, if the threat is registered, act to bolster the status quo. This research indicates that both executive succession and strategic reorientations are important strategic levers affecting organization evolution. Those most effective organizations initiated proactive reorientations with no top executive succession.[156]

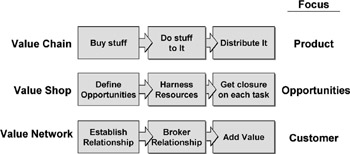

The primary factor in the development of business processes, ultimately influencing the structure of their supporting organizations, is the orientation of the combined output of the firm. Put simply, at the core of an organization’s value proposition is typically an oversimplified, single intentional focus, as depicted in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3: The process of value (adapted from Stabell and Fjeldstad)

The Influence of Technology

In recent years, technology has played an ever-increasing role in reshaping the structure of organizations, as business processes redefine themselves for greater efficiencies and individuals embrace new capabilities. In 1995, Rayport and Sviokla introduced the concept of a virtual value chain as ‘[...] the value that can be generated by exploiting the information generated by any stage of this process’.[157] This observation can be modified and applied to how enterprises are leveraging technology to enhance the structure of information and ultimately their organizations.

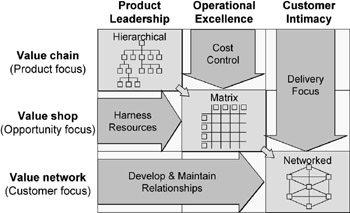

Technology is giving organizations new options on when work can be accomplished, where, how and by whom. In effect, technology is shrinking and expanding the effective time in which businesses can operate. Workers can execute activities from anywhere at anytime. In many cases, the lines between work time and personal time are becoming blurred. The capabilities that technology brings to the act of working also introduce new issues including: a reduced amount of physical contact with co-workers; non-adherence to conventional rules; and a sense of loyalty to oneself, not to the firm. The new structure of work influences workers’ renumeration systems, which are now assessed by their contribution to a collaborative project, not by the direct proportion of time spent working on any specific activity. This new organizational dynamism is giving birth to three distinct organizational structures: value chain, value shop and value network.[158] When the organizational structures identified by Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998) are overlaid onto the value discipline framework introduced by Treacy and Wiersema (1995) in The Discipline of Market Leaders, the focus of the organizational output can be correlated to its underlying structure as seen in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4: Organizational migration (adapted from Stabell and Fjeldstad)

Since technology is continually redefining many of our traditional constraints to organizational structure, the opportunity for business is to reassess its structure as a component of added value and determine which structure provides the greatest competitive advantage. It would be unwise to assume that all organizations will develop fundamentally different structures, and even more naive to think they will all embrace one structure. Finding the right structure to maximize the convergence of technology and talent is a process of harmonizing these factors, as noted by Lipnack and Stamps: ‘You can match the work to the right form of organization by understanding what teams can do, when hierarchy applies, what is useful in bureaucracy, what circumstances call for networks – and how to fit them together.’[159]

In order to achieve organizational excellence, companies need to align their processes with technology and skilled individuals into a coherent structure that continually assesses productivity and efficiency. Organizations that apply technology to become best in class in a single business process or sub-process often achieve their goal at the detriment of the overall process levels. Consistency within and across a process is, in many cases, a better application of resources, as it raises the aggregate level of performance, as Quinn points out:

Companies seeking strategic advantage through significant technological innovation need to recognize the tumultuous, long-term realities of how this process operates, and design specific organizations and management practices to motivate it and guide it.[160]

Technologies such as the Internet amplify the need for a holistic approach to process management, especially when there is a requirement to integrate new functions seamlessly. Firms often lose sight of the implications of process changes which, in many cases, alienate customers during the transition process.

The Influence of Virtual Products

The technologies of the Internet, telecommunications, databases and other information processors have ushered in a new era of business in a global marketplace. As we have discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, the definition of what constitutes a product, a distribution channel and a customer is continually changing, in tune with social and cultural preferences. These factors have brought technology-based products, people who understand the application of technology and technology itself to the forefront of strategic initiatives and to the core of business process design. Castells notes the importance of technological prowess to a firm’s value proposition: ‘the new economy is organized around global networks of capital, management, and information, whose access to technological know-how is at the roots of productivity and competitiveness’.[161] Customers are keenly aware of the intrinsic value that technology brings to enhancing their lifestyles and now, as the next generation of technology is introduced to the marketplace, business will take the same approach. Davidow and Malone remind us that the application of technology does not make us abdicate our own individual responsibility to synthesizing information into strategic actions:

The business revolution caused by virtual products will be led by companies in established industries that have recognized the potential of using some or all of the four kinds of information to reconstruct their business. They will be companies that are observant enough to spot a technological crossover threat emerging in some distant industry and race to incorporate it. They will be the ones that develop multidisciplinary inventions themselves. In every case, technology will be subordinate to, not a substitute for, a complete understanding of the market and the business.[162]

Business entities across the globe are looking towards technology as the primary mechanism for adding value to customers. However, Davidow and Malone also point out: ‘because many virtual products of the future will be almost solely the creation of technology, there is a danger that business executives will become overly reliant on it.’[163] Technology is only a part of the value equation; people and process are the other two ingredients.

The Implications of the Virtual Organization

The collaborative influence of technology now presents business with the ability to fundamentally rethink its products, the relationship with customers and suppliers, the markets and the structure of the organization.

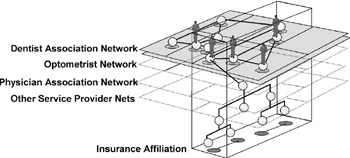

The value network is not simply connecting computers and sending eMails to each other, thereby increasing communications. It is a collection of collaborative technologies working with established business processes to distribute information to where it is most needed to support the horizontal process of business and the vertical hierarchy of organizational structure. The expressed goal is to increase the level of communications so that individuals can act intelligently and make decisions in a dynamic, competitive environment. However, the implied goal is not merely to subject everyone to an avalanche of detailed information (which is evident in corporate eMails); it is to provide data to individuals to participate in the business process effectively. Figure 5.5 presents a theoretical framework for a collaborative virtual healthcare system, in which the structure of the information centres on the patient, not on the individual organizations performing medical procedures.

Figure 5.5: Collaborative virtual healthcare

The opportunity to share patient information and broker insurance transactions will fundamentally change the way healthcare is delivered in the next decades. A patient whose records are shared and accessed via loosely coupled servers may use a variety of dental specialists within or outside a specific insurance network with electronic co-payments and imaged records. So how can this type of system add value to healthcare customers and patients?

At the junction of the healthcare network is patient information. Coupling the healthcare network infrastructure with an existing Internet offering such as Minnesota’s Medformation.com,[164] which acts as a destination for medical customers, creates an environment with significant potential savings for providers and patients. The value proposition of Medformation.com is twofold: proactive health maintenance (providing information on staying healthy) and reactive healthcare, enabling individuals to do a limited amount of simple self-diagnosis and brokering relationships for the patient to a variety of healthcare providers. The overall value can be plotted into three distinct groups: patients or customers, healthcare professionals and healthcare administrators. Each group requires information that essentially stems from the patient but may only be loosely associated to specific data about the patient, such as a doctor may wish to know how many people used the hospital for cancer treatment in the last year. Patients will want to confirm their medical records, the status of any current procedures, reconfirm their benefits and look at general medical information. Physicians and other healthcare professionals will check the status of current medical tests, issue prescriptions, search patients’ medical histories and schedule additional procedures. Healthcare administrators will review cases, coordinate benefits and other administrative functions.

The virtual networked organization has been defined as a network of organizations coming together in response to a market opportunity. These virtual organizations share skills, costs, and market access. Each member of the virtual organization brings a core competency to the group.[165] Key elements that define the virtual organization include opportunism, technology, excellence, trust and lack of organizational borders. The information technology supporting the virtual organization model is varied, ranging from simple communications technology such as teleconferencing to the sharing of databases, computer-aided design and manufacturing information and interorganizational linkages.[166]

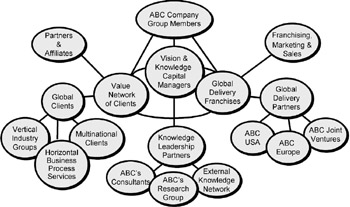

Examples of virtual organizations include a variety of strategic alliances, partnering and outsourcing situations, as depicted in Figure 5.6, the molecular organization. This model emulates an example of a large multinational business engaged in joint product development and international market access with distribution partners. Small firms’ models have included a number of consortia that bring together smaller manufacturers[167] using the same basic collaborative process and organizational framework.

Figure 5.6: The molecular organization

The reasons for adopting the virtual organization model would be similar for the new venture and the existing enterprise, perhaps with a few differences in degrees of importance. The virtual organization offers the sharing of common infrastructure such as networks and expensive resources, collaborated research and development, shared risks and costs between partners. Another aspect of the virtual organization is linking complementary core competencies and other communities of practice to exchange ideas and designs. Reducing the time to market and gaining new access to markets is a by-product of the networked relationship, in that partners, associates and affiliates each bring to the network a link to other networks which act as gateways to other niche markets. Finally, the virtual organization brings an opportunity to build an associative brand, and can be leveraged to build customer loyalty to a corporation or product identity. The effectiveness of the virtual organization is proportional to the investment made in the corporate infrastructure. However, firms are now realizing that the change of structure from command and control to control and command needs to be accompanied by an equally drastic redefinition of the way in which the organizational culture perceives strategic decision making, as Pacey observes:

One way of expressing the issues raised by the technology-based bureaucracies, and by the big multinational companies, is to say that nations which are nominally democratic are finding that large sectors of decision-making have been taken over by totalitarian institutions.[168]

One clear aspect of the virtual organization structure and the hybrid organizations that it brings to life is a direct distribution of decision making and resource consumption. One could argue that this type of organization pushes the management of the company’s business processes down to where the action is, that is, the process itself. The traditional senior management team now acts as a resource that is used by the individual operating processes, as needed in roles such as mentor, problem solver and other functions that require cross-process knowledge and industry expertise. Davidow and Malone detail the extent to which the emergence of the virtual corporation will influence our traditional notions of worker and employer:

Several changes do, however, appear inevitable, given the increasing technological orientation of corporations, the distribution of decision making out to the rank and file, the less distinct boundaries between the company and its suppliers and customers, and the perpetually accelerating cycle times. These changes include the following:

-

More sophisticated training will continue through employers’ careers.

-

Cross-disciplinary organizations, such as work teams, will have extensive decision-making powers.

-

Hiring policies will select for adaptability to change.

-

An unprecedented emphasis will be put on retaining existing employees in a shrinking labor pool.

-

Unions (where they still exist) and management will enter into different, mutually dependent relationships.

-

The traditional notion of career will be redefined.

-

The potential will exist for a different form of worker alienation.[169]

Therefore, in line with the continued rate of technological advancement, organizations will transform into value chains, value shops or value networks and their technological infrastructure will enable a redefinition of the organizational structure to support a host of new and yet unimagined business processes. This is not merely a ‘Brave New World’ vision: it is a perfectly conceivable future, one that is becoming more and more real every day. As Stabell and Fjeldstad observe:

The business value systems reflect the activity interrelationships and drivers of the respective underlying value configurations. Value chains form sequentially interrelated value systems of suppliers, producers and distributors, each adding value to the output from the preceding chain. Value shops are linked and referred in a wheels-outside-wheels relationship to specialized problem-solving and implementation activities. Value networks form coproducing layers of mediators where one network may use a lower-level network as a subnetwork. In addition value networks form horizontal interconnected value systems of similar firms that extend the scope of the network by virtual mergers to gain mutual benefits from network externalities. The resulting scope is equivalent to the horizontal union of the vertical intersection of customer contracts. Most business value systems include firms representing all value creation logics.[170]

[155]G. R. Bushe and A. B. Shani, Parallel Learning Structures. Increasing Innovation in Bureaucracies (Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley, 1991) p. 3.

[156]M. L. Tushman, B. Virany and E. Romanelli, ‘Executive Succession, Strategic Reorientations, and Organization Evolution’. In M. Horwitch (ed.) Technology in the Modern Corporation: a Strategic Perspective (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1986) p. 215.

[157]F. Czerniawska and G. Potter, Business in a Virtual World: Exploiting Information for Competitive Advantage (Basingstoke: Macmillan – now Palgrave Macmillan, 1998) p. 68.

[158]C. Stabell and fl. Fjeldstad, ‘Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, Number 5 (1998) p. 413.

[159]J. Lipnack and J. Stamps, The Age of the Network (Essex Junction: Oliver Wight, 1994) p. 20.

[160]J. B. Quinn, ‘Innovation and Corporate Strategy’. In M. Horwitch (ed.) Technology in the Modern Corporation (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1986) p. 169.

[161]M. Castells, The Rise of the Network Society (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997) p. 471.

[162]W. H. Davidow and M. S. Malone, The Virtual Corporation. Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century (London: Harper Business, 1993) p. 85.

[163]Ibid.

[164]Medformation.com is a community service of Allina Hospitals and Clinics, a hospital and clinic system serving Minnesota and western Wisconsin. See http://medformation.com.

[165]J. A. Byrne, R. Brandt and O. Port, ‘The Virtual Corporation’, BusinessWeek, February 8 (1993) pp. 98–103.

[166]See S. L. Goldman, R. N. Nagel and K. Preiss, Agile Competitors and Virtual Organizations: Strategies for Enriching the Customer (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995).

[167]See W. H. Davidow and M. S. Malone, The Virtual Corporation. Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century (London: Harper Business, 1993).

[168]A. Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983) p. 134.

[169]W. H. Davidow and M. S. Malone, The Virtual Corporation. Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century (London: Harper Business, 1993) p. 187.

[170]C. Stabell and fl. Fjeldstad, ‘Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, Number 5 (1998) p. 435.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 77