The Nature of Bureaucracies

Corporations as a living culture develop bureaucratic structures to control the process of business that in effect extends from the founders’ original thinking on how the organization should function to the latest recruits, through rules, procedures and policies. This traditional command and control philosophy endorses the concept that an elite group within the firm contains all the knowledge needed to execute the production of the business processes. In theory, this method enables a small group of individuals to channel all the information about the activities of production to them for problem resolution. Likewise, this structure assumes that individuals within the organization need very little cognitive skills and merely follow directions to ensure the timely execution of the firm’s business activity.

In order to legitimize this structural need to control and disseminate information, organizations develop business processes which often contain similarities, although they may be designed by different groups within the firm, as Bushe and Shani describe:

All organizations, however designed, share certain attributes. All involve division and coordination of tasks; all transform inputs into outputs; all involve information processing; and all require an uneven distribution of legitimate authority. The essence of bureaucratic organization is the production of standardized, predictable, replicable performance by many different people and/or groups.[49]

In other words, we create bureaucracies to administer the activities that are expected to be executed by the business processes in a normative state. This often hierarchical alignment of resources is primarily designed to codify activities in order to achieve an economy of scale. Hammer describes the incongruity that business management faces when considering the structure and function of organizations:

Modern organizations have learned that the notion of economy of scale has severe limits. With size come diseconomies of scale. As organizations grow, multiple layers of administrative bureaucracy inevitably appear and it becomes difficult for any individual to have an overall understanding of what’s going on. Breaking a large organization into several smaller ones avoids this problem, but at the possible price of inconsistency.[50]

The concept of ‘reengineering’ coupled with the new array of information and telecommunications technologies increased the range of alternatives for business to rethink the relationship between organization and process. The matter in question is the overall proportional relationship between the complexity that an organization acquires over time due to changes in the competitive climate and the administrative control of information needed to govern the process.

In his examination of the nature of organizations and their relationship with technology as part of the evolution to a ‘benevolent bureaucracy’, Petrella identifies the principal elements of diffusion and distribution of information:

On the one hand, since the degree of complexity depends on the number and nature of the interactions between the elements of the system, the access to power (that is, to the capacity of mastering the complexity) will depend upon the control of the information flows between the elements, in the subsystems and between the subsystems. This means that a benevolent bureaucracy will depend upon the diffusion and the distribution of the control mechanisms of the information flows. Evidence suggests that the diffusion and the distribution are not the norm, today![51]

Therefore, simply adding technology to the existing bureaucratic structure as a method of increasing productivity, while processes become more and more complex, may actually hamper the organization’s ability to cope with the additional levels of complexity. It is clear that organizations must deal with the new complexity of business not by adding technology, but by redefining its application to a new structure. This introduces another dilemma for organizations, the complexity of a ‘nested bureaucracy’, that is, the bureaucracy of the technology organizations operating within the larger corporate bureaucracy. Subdivisions of organizations develop policies and procedures that are used as mechanisms to control the business processes executed by the organization and to define the behaviour of individuals performing tasks to support processes during a variety of business conditions. However, in many cases organizations which provide supportive or administrative devices to a primary business process develop their own secondary process, one which over time often works as a retarding agent to the primary business process activity. These added layers of bureaucracy in many cases replicate the controls of the primary process and place a higher level of granularity to the parameters that control the process. This higher degree of specificity is the crux of the nested bureaucracy, and leads to an eventual need for business realignment of organizational goals and objectives. Here again Petrella indicates the dual problem of ‘access to the knowledge of the system’ as a desired goal, and the needs of specialization as a potential counterweight to any theoretical productivity gains that should be realized in reducing a corporate bureaucracy:

On the other hand, the greater the complexity, the greater must be the access from people and the organization to the knowledge of the system. Now, since this knowledge is a resource limited (in normal situation) to a restricted circle of ‘specialists’ (the so-called technocrats), it is reasonable to infer that for the time being the ‘explosion’ of the complexity and the requirements for its mastering are not going in the direction of the enlargement of the basis for a benevolent bureaucracy but rather this enhances the foundations for a technocratic bureaucracy.[52]

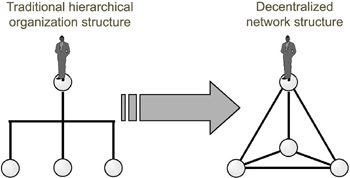

Petrella realizes that technology can indeed minimize the inherent delays normally caused by bureaucracy in the process of business, and that the ultimate goal of technology would be to make a bureaucracy invisible or benevolent to any business process. However, in the establishment of a technology organization, another bureaucracy may form, thus annulling the gains associated with the reduction of the initial corporate bureaucracy. In order to combat this condition, the fundamental characteristic of structure should be examined relative to the relationships between process and technology. Lipnack and Stamps provide an oversimplification of these issues which provides a framework for thinking in which an organization can strike a balance between the inhibiting forces, as seen in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Using technology to change bureaucracy

Organizations in transition require stability to neutralize the drain on resources that occurs when competitive forces place additional strain on the firm’s resources, already expending energy on an internal realignment. Lipnack and Stamps point out that the two contributing factors which tend to create organizational stability are those of the command-and-control vertical hierarchy which is often without knowledgeable depth, and a bureaucratic process that is overlaid on to the struture. These two factors create a 3-dimensional view of the traditional organization and resemble a three-legged stool. However, in this example, three-legged stools are often overturned if a high velocity wind is applied across the top of the stool because the feet are not tied together, forming a stable base. By adding links between the lower nodes of the hierarchy-bureaucracy, stability is maintained by a structure symbolized as a tetrahedron, which Buckminster Fuller described as the universe’s minimal closed structure. Lipnack and Stamps expertly put it into a simple axiom: ‘To convert a hierarchy-bureaucracy to a network, just add links.’[53] One could argue that simply increasing the connectivity between people in the organization reduces the bureaucratic delays or ‘organizational latency’ because information no longer has to move up and down a hierarchical structure. Information can be broadcast to all individuals (network nodes) who need it in order to execute process functions. The elements of the bureaucratic conundrum will be explored throughout this chapter. The role that technology plays in changing our conception of bureaucracies will also be discussed in Chapter 5.

That said, if we strip away the technological aspect of corporate bureaucracies and how it adds value in business environments growing in complexity, we are left with the question of what is different in today’s society, workforce and customer behaviour from previous decades. Berleur characterizes the problem in pondering the new information society:

Underlying the link between bureaucracy and scientific and industrial society is an heuristic way of questioning the meaning of the so-called ‘information society’. Is there any difference between an ‘energy society’, which could characterize the industrial age and an ‘information society’ of the post-industrial time?[54]

Almost half a century ago, Jay Forrester of MIT put forward an interesting question: society is bold in creating and adopting technology to test ideas which lead to major advances; however, why are societies timid when changes concern conventional social practices?[55] In the new information society, we have the opportunity to change the world, the structure of political, social and economic processes and practices. To do this, however, certain practices such as those of corporate bureaucracies must be modified. It is to the attitudes and potential elements of change in corporate bureaucracies that we now turn.

[49]G. R. Bushe and A. B. Shani, Parallel Learning Structures. Increasing Innovation in Bureaucracies (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1991) p. 5.

[50]M. Hammer, Beyond Reengineering: How the Process-centred Organization is Changing Our Work and Our Lives (London: HarperCollins, 1998) p. 189.

[51]R. Petrella, ‘In Search of … the Benevolent Bureaucracy’. In L. Yngstr m, R. Sizer, J. Berleur and R. Laufer (eds) Can Information Technology result in Benevolent Bureaucracies? (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 1991) p. 20.

[52]Ibid.

[53]J. Lipnack and J. Stamps, The Age of the Network: Organizing Principles for the 21st Century (Essex Junction, VT: Oliver Wight, 1994) pp. 71–3; citation on p. 72.

[54]J. Berleur, ‘The so-called “Information Society”’. In L. Yngstr m, R. Sizer, J. Berleur and R. Laufer (eds) Can Information Technology result in Benevolent Bureaucracies? (Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 1991) p. 23.

[55]J. Naisbitt and P. Aburdene, Re-inventing the Corporation. Transforming Your Job and Your Company for the New Information Society (London: Macdonald, 1985) pp. 40–1.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 77