Privacy Legislation

While privacy as a subjective viewpoint or as a topic of ethical study may be understood in various ways, it must be rendered in quite hard and fast terms when it comes to legislation. Privacy legislation, explicitly labeled as such, is primarily about protecting privacy as opposed to outlawing privacy. When a type of personal information falls outside the scope of legislation, privacy can be said to be unprotected.

Once an aspect of privacy is unprotected, then it should not be assumed that there is any mechanism in place that provides privacy control with respect to that aspect. For example, there may be no law against an individual-when in a public place and regardless of the nature of the observer-being visually observed in terms of how they look, and what they are wearing, what they are doing, and who they are with. In this case, it should not be assumed by the individual that there is protection against this loss of privacy-whether they feel it is natural law or not.

Much of the technical discussion in this book has pointed out that an access network operator is able to put physical mechanisms in place to determine the location of a device using that network. Where the operator has the means to associate a person's identity with that device, then they are in a position of control with respect to this piece of privacy information. Note that the existence (or otherwise) of a protocol such as HELD does not change this situation; the mechanisms for determining location and associating it with a person's identity exist independently of the protocol. Using a network where location and identity can be associated means trusting the operator of the network with respect to maintaining the privacy of that information. Legislation is the only basis for assuming that this privacy is protected whether it is legislation directly addressing location information or legislation preventing a network operator from making false or misleading assurances with respect to that privacy.

On the specific topic of protecting the privacy of information associating instantaneous or historical location with identity, legislation is not necessarily clear. Examining the Australian Privacy Act of 1988 (see Reference 1) as an example, the focus is on records of information kept about a person, the manner in which information is solicited, notification to the person with respect to the existence of the records, and details of any access to those records, ensuring the person themselves have access and, of course, the circumstances under which third parties should be able to access the records. Typical records identified in the act are credit details, medical history, and similar forms of data. Indeed, the act defines a record as meaning

-

A document

-

A database (however kept)

-

A photograph or other pictorial representation of a person

It is a matter of interpretation as to whether the instantaneous location of a person as determined by a network constitutes a "record" as far as the intent of this act goes. A historical record of their location may more readily fit the definition. Similarly, any legislation based on the OECD privacy guidelines [OECD-Privacy-1980] may leave the inclusion of instantaneous location information within its scope open to interpretation.

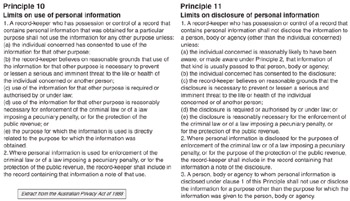

Where legislation is considered to cover location, the rules governing it are likely to be similar to those relating to more conventional forms of personal records. Going back to Reference 1, the act defines 11 information privacy principles (see Figure 10.1). Most deal with the manner of collection, storage, and management of the records, and the access rights of the person being the subject of the records. Principles 10 and 11, however, detail the limits on the use and disclosure of personal information.

Figure 10.1: Two privacy principles from the Australian Privacy Act of 1988.

Australian laws are chosen because they are considered a model application of the OECD guidelines. Similar laws have been adopted by other OECD nations, although in the United States, each state administers its own privacy laws. The U.S. situation means that large organizations might operate under different laws. As of 2006, uniform federal laws were being sought by a number of large technology companies.

Such rules are typical in the sense that the information is to be kept confidential unless the user has given consent, the information is used for the (agreed) purpose for which it was created, or disclosure is required for safety or law enforcement authority purposes. In accordance with such constraints, network technology governing the control of location information should be able to support corresponding controls. Regardless of the fact that such controls may be latent in network technology, as mentioned previously, the activation of the controls can only be safely assumed where a legislative imperative to do so exists.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 129