Assessing Risk

|

|

After a project enters the development phase, events may affect the project timeline, costs, or budget. A difficult aspect of project management is finding ways to complete a project successfully in an environment in which any of the following can occur:

-

Contracted resources are suddenly unavailable

-

Members of the project team terminate employment or transfer out of the project team

-

Severe weather causes delays for outdoor tasks

-

Customers or stakeholders add deliverables

-

Tasks take more or less time than scheduled

-

Labor disputes delay project activities or increase costs

-

Costs for material resources increase substantially

Risk management has three components—assessing, planning, and managing risks— that can affect the project timeline, scope, or budget.

Some naïve project managers feel that risk analysis leads to negativity, so they limit the team members’ involvement in risk analysis. Other managers feel their personal crisis-management skills will overcome any possible problems, so they skip or give short shrift to the risk analysis. The real function of risk analysis is to ensure that unforeseeable events are what might kick your project off track, as opposed to unexamined events. We recommend a thorough risk analysis, and the creation of contingency plans to manage or respond to events that can put a project seriously over budget or behind schedule.

When you assess risks, you’ll focus on project activities and external factors that increase project uncertainty. Begin by focusing on three types of project tasks:

-

Tasks that have estimated durations

-

Tasks with external predecessors that are partially or completely outside the project manager’s control

-

Tasks with long durations

Viewing Tasks with Uncertain Duration

To analyze risks, begin with the unknown aspects of your project. Examine the tasks that have estimated durations, and nail the durations down before the development phase.

To view tasks with estimated durations, first turn off AutoFilter if AutoFilter is turned on (Project Ø Filtered For Ø AutoFilter); then, follow these steps:

-

Choose View Ø Gantt Chart.

-

Choose Project Ø Filtered For Ø Tasks with Estimated Durations.

The Gantt chart will include only tasks with estimated durations. For each task in the Gantt chart, determine why the duration is estimated. If you can enter the task’s duration, do so now. For strategies to analyze task duration, see “Using PERT to Estimate Duration,” later in this chapter.

Viewing Tasks with External Dependencies

Tasks that depend on tasks or deliverables from other projects require special consideration. If a task’s predecessors are in another project, schedule changes in the other project can impact your project’s schedule. For example, one of the deliverables for the marketing project you’re managing is a brochure that includes pictures of a product’s prototype. Creation of the prototype is a deliverable for another project; therefore, the activities to create the prototype are not within your control. The prototype may not be created on time.

The XYZ Branch Office Training project, created in Chapters 2 through 5, was split into two separate projects. Training setup and delivery remain in the original XYZ-BOT project file; curriculum development, printing, and shipping have been placed in a separate project: XYZ Materials. The Materials project is being managed by the training development supervisor.

In the XYZ-BOT project, the final task in the Materials project, Schedule Delivery, appears as a task in the Gantt chart. The task’s bar is gray to indicate that it is an external task, as shown in Figure 13.1. If you double-click an external task in the task table, Project opens the external project file.

Figure 13.1: External tasks are included in the Gantt chart.

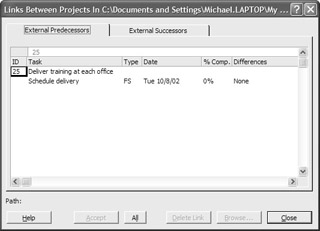

If the external predecessors are being managed in Project, you’ll get good information about the predecessor. By default, you are notified when information about a task in an externally linked project changes. When you open a file that contains links to another project that has changed, Project opens the Links Between Projects dialog box, shown in Figure 13.2, to display the status of external predecessors and successors, and their impact on your project’s schedule. (You can manually display this dialog box by selecting Tools Ø Links Between Projects.) Click either the External Predecessors or External Successors tab to view tasks linked to other projects.

Figure 13.2: The Links Between Projects dialog box.

| Note | See Chapter 14 for more information about external links. |

Project makes it easy to communicate about interproject dependencies. When your project depends on external projects that are not managed in Project, you must establish your communication requirements with the other PMs. It’s a good idea to add visual cues to tasks with external dependencies so they stand out in the Gantt chart. Select the task, choose Format Ø Font to open the Font dialog box, and choose a different font or color for external tasks.

You can also add a custom field to a task to record an external dependency. See Chapter 25 for information on custom fields.

Viewing Tasks with Long Durations

If a task is scheduled to start on Monday and finish two days later on Wednesday, it’s easy to notice if it falls a few days behind schedule. With longer tasks, delays of three days, three weeks, or even three months can be harder to recognize. Even when you use Project’s workgroup communication tools to request regular updates, it’s sometimes hard to know that a task with a long duration is slipping.

| Tip | Longer-duration tasks are less flexible than a series of shorter-duration tasks. When possible, break a task into smaller work packages to increase scheduling flexibility. |

It is easy to understand why long-duration tasks often fall behind schedule. Short-duration tasks provide little room to maneuver. Team members realize that a two-day task needs to be started two days before the finish date. There are, after all, only two days when team members can work overtime to make up for a late start. The completion date is only two days away, which makes the deadline very real. After the first day, team members have a good idea of the task’s status. They can quantify the number of hours spent on the task, and know how many are left to go.

Team members may report that a task with a distant deadline is on schedule when little or no time has been spent on the task. With longer durations, team members have more days that they can come in early or stay late to play “catch up” before the scheduled finish date. The task deadline is a long way off, whereas other tasks’ deadlines (such as that two-day task) are imminent. It may not be practical for the team to work 16 hours tomorrow to get a two-day task back on track, but team members rationalize that they can find 8 extra hours sometime in the next month to make up for missing 8 hours of work on today’s task. When the project team focuses on completing each task by the scheduled finish date, the schedule for longer duration tasks is often compromised so that shorter duration tasks can be completed.

To view tasks with longer duration:

-

Switch to Gantt Chart view (View Ø Gantt Chart).

-

Display the Entry table (View Ø Table Entry) or another table that includes Duration.

OR

Right-click on the table, choose Insert Column from the shortcut menu, and insert the Duration column.

-

Turn on AutoFilters (Project Ø Filtered For Ø AutoFilter, or click the AutoFilter button on the Standard toolbar) to display drop-down arrows in the table’s column headers.

-

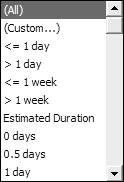

Click the AutoFilter drop-down arrow in the column header for the Duration field.

-

Choose a duration from the drop-down list.

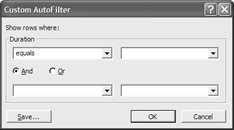

Alternately, you can choose Custom to specify a duration in the Custom AutoFilter dialog box.

Identifying and Managing Other Risks

Viewing tasks with estimated duration, long duration, or external dependencies focuses on task-based risks. Now that you’ve examined the trees, step back and look at the entire forest using contingency planning and force-field analysis. With these tools, you’ll ask two questions: What can go wrong, and what are the forces that support and oppose the project?

Creating a Contingency Plan

A contingency plan is a list of events that would impact the project schedule or budget, and plans for handling those events if they occur. For a small project in your area of expertise, you may be able to answer the question, “What can go wrong?” For larger projects that involve specific technical expertise, assemble members of the project team and brainstorm a list of events that may occur during the life of the project.

Some team members might have difficulty answering the broad question, “What can go wrong?” Here are other ways to ask this question that our team members have found helpful:

-

What real or potential obstacles would prevent you from performing your assignments as scheduled?

-

What guarantees do you need to be able to ensure that you can perform your assignments as scheduled?

-

What do you need from the project manager to guarantee your success with this project?

-

Do you see any places where you might expect difficulties in the project schedule? If so, where?

For the XYZ Branch Office Training project, our risk list included the following:

-

No training facilities for lease at one or more locations

-

Sudden loss of a trainer (personal illness, family illness, or death)

-

Incorrect software installed on computers in rented facilities

-

Pretests completed too late to be used to drive course content

-

Travel problems: cancelled flights, missed connections, weather delays

-

Shipped materials don’t arrive before training starts

After you identify the risks, develop contingencies to counter each risk. Our risk and contingency analysis is shown in Table 13.1.

| Risk | Contingency |

|---|---|

| Sudden unavailability of leased lab | Lease laptops and arrange nearby hotel space. |

| Leased lab is unsuitable | Arrange for branch office director to assign staff to visit and approve leased lab. |

| Loss of a trainer | Assign backup trainer for each training. Make sure that one trainer is unscheduled during each week of training. |

| Incorrect software installed on computers in rented facilities | Have trainer arrive one day in advance to check facility. Provide the trainer with correct software for emergency installation. |

| Pretests completed too late to be usedtodrive course content | Develop initial curricula without pretest. Increase the delay between pretest release and curricula finalization. |

| Travel problems: cancelled flights, missed connections, weather delays | Fly the trainer to location one day in advance. |

| Shipped materials don’t arrive before training starts | Provide the trainer with master copy of materials for onsite duplication. Verify receipt of shipped materials with each site. |

You can’t develop a contingency for every risk. If the only airport within 500 miles of the training site is closed for two days because of unusually heavy snowfall, a hurricane, or other unforeseen situations, travel delay is unavoidable. Brainstorm contingencies where possible; then decide which contingencies to build into the project plan and which to hold on reserve, based on the likelihood of the risk events and the cost of including the contingency.

| Note | At least one member of every project team can fantasize and defend a list of events that stretch credulity. When someone suggests that “the end of life as we know it” would compromise your project timeline, don’t start an exhaustive search for contingencies. Reframe the discussion. |

In Table 13.1, for example, having the trainers arrive at the training site one day in advance covers two areas of risk. By arriving a day early, trainers can check to make sure that the software installed at the training site is correct, and they can minimize the risk associated with cancelled flights and missed connections. The costs to implement this contingency include increased expenses for accommodations and trainer pay, but those may be acceptable costs compared to the costs of rescheduling part or all of a training course. Some contingencies have little or no cost, such as providing trainers with master copies of materials, or verifying the receipt of materials shipped to individual sites.

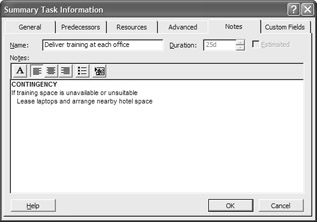

Storing the Contingency Plan

The contingency plan document, which doesn’t need to be any more formal than Table 13.1, should be linked to the project summary task. If you need the contingency plan, you probably won’t have extra time to search for it! For task-related contingencies such as renting laptops and hotel space, use copy and paste to include the contingency in the task’s Notes tab:

Identifying Environmental Risks

Force-field analysis is a tool used by project managers to understand a project’s external environment. The results of the analysis are two lists of forces—positive and negative—that may impact the project. In many organizations, force-field analysis is completed prior to project design. If the negative forces aligned against a project are immense, the project never enters the design phase. See if a force-field analysis has been completed before starting your own analysis.

Unlike the risk/contingency analysis, a force-field analysis is not task-oriented. You may want to complete the force-field analysis on your own, with another project manager, or with your immediate supervisor. The tool is simple: Create a two-column list in Word, Excel, or on a sheet of paper. Label one column Positive; label the other Negative. In the Positive column, list the forces that will support or assist with the project. In the Negative column, list the forces that will oppose or resist the project. The force-field analysis for our sample XZY Branch Office Training project is shown in Table 13.2.

| Positive | Negative |

|---|---|

| Support from XYZ management | Resistance to training by outsiders |

| Solid trainers | Branch offices traditionally oppose or resist “main office initiatives” |

| XYZ’s commitment to professional development | Employees required to take time from regular tasks to attend training |

| Industry-wide interest in training and certification | Trainers’ concern about extended time out-of-state |

| XYZ involvement in TQM process | Employees’ reluctance to participate in workplace tests |

With formal force-field analysis, the next step is to estimate the strength of each positive and each negative force, using a scale of 1 to 10 or 1 to 100. The positive and negative columns are then totaled and compared. If the positive total vastly outweighs the negative total, the analysis indicates that the project will succeed. If the negative total outweighs the positive total or if the two are close, the project is not likely to succeed. This leaves five possible courses of action:

-

Redesign the project to eliminate negative forces.

-

Cancel the project.

-

Bolster the positive forces so they significantly outweigh the negative forces.

-

Weaken the negative forces so positive forces significantly outweigh them.

-

Develop strategies that bypass the negative forces.

Many project managers, including the authors of this book, are more comfortable with a less-quantified use of force-field analysis. Accurately naming the forces that impact project success is difficult. The “value” of the strength of the organizational and societal forces identified in the analysis often becomes little more than guesswork. Assigning a numerical importance or strength to each force creates a false sense of precision that can drive poor decisions and wasted effort.

After developing the list of positive and negative forces, we suggest that you view the positives as forces to be maintained and leveraged through the life of the project. The project manager has plenty of opportunities to recognize and strengthen positive forces. For example:

-

Project reports can recognize and reinforce the positive forces. In our sample project, one of the positive forces is XYZ Corporation’s involvement in Total Quality Management. We could integrate information about our company’s TQM efforts in this project into our project reports.

-

Information about how this training project reflects the industry-wide movement for training and certification could be easily integrated in a project proposal or project evaluation.

-

Informal communications can strengthen and build on the positive forces. We could send personal notes to our trainers to remind them that their expertise is valued and recognized.

Negative forces are often the outgrowth of personal concerns about job security, quality of life, or power within an organization: individual issues can become larger than life as the project progresses. Rather than declare war on negative forces, the project manager can look for ways to downplay or address negative forces without compromising the project plan, such as:

-

One of the negative forces is our trainers’ concern about extended time out-of-state for training at the branch offices. We could counter this concern by recognizing the concern, and asking how we can make the extended time out-of-state more palatable.

-

To neutralize the resistance of branch offices to main office initiatives, we could contact each branch office manager to solicit their input about training and training design—and send a handwritten thank-you note after the conversation.

Force-field analysis isn’t the most important tool in the project manager’s toolkit. Used wisely, though, the analysis identifies the strengths you can build on, and the weaknesses that need to be understood and neutralized as the project progresses.

|

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 241

- ERP System Acquisition: A Process Model and Results From an Austrian Survey

- The Second Wave ERP Market: An Australian Viewpoint

- Enterprise Application Integration: New Solutions for a Solved Problem or a Challenging Research Field?

- Distributed Data Warehouse for Geo-spatial Services

- Data Mining for Business Process Reengineering