The Cost of Doing Nothing

One of the most common systems of evaluation that customers use is the cost of doing nothing. As shown in the list in Exhibit 3-4, this SOE favors existing suppliers or status quo. The cost-of-doing-nothing SOE becomes more prevalent during economic downturns. The most effective way to overcome this SOE is to substitute one that calculates the measurable benefits from achieving suggested goals on a per diem basis. Use SOEs to help customers measure the dollar difference between what they are doing now and the goal they want to achieve. When customers realize what potential savings or revenue they are losing daily it increases their sense of urgency.

For example, your products can reduce customers' operating expenses by $300,000 annually. Instead of focusing on this annual savings amount, point out to customers that every day they lose the opportunity to save $822. Demonstrating that time is money is a powerful way to overcome the cost of doing nothing that favors existing suppliers. You might also want to point out to customers how much products and/or services their companies must sell to generate $300,000 worth of savings—if a company has a 10 percent profit margin, they must sell $3,000,000 to equal savings of $300,000.

Making Goals Measurable

With apologies to the movie Field of Dreams, if you help customers measure their goals, they will come. Customers and you both want to know whether customers are getting the most value possible. When you build value from their goals down, not from your features up, everyone does know. To ensure repeat business, ensure that customers achieve their goals every time they do business with you. If you always start with their goals, not your products, you will reduce the chances of unfulfilled expectations. The first time they do not achieve their goals you will remember the following sales adage: "Competitors do not win over your customers; you unwillingly lose them due to unfulfilled expectations."

Yet, if you do not make customers' goals measurable, you risk losing them. Ironically, you usually find out how customers measure the value of their goals after you lose a sale or disappoint a customer. A statement such as, "I thought you were looking for it to do this, not that," indicates you were measuring their goals differently than they were.

You also risk having customers who cannot tell that you provided more value than competitors—so they will not compensate you for doing so. Finally, without measurable goals, it is hard to guess how customers who purchased your products will judge the merit of them. You want your customers to look back on any purchase they made from you and be able to measure how it achieved their goals. When this occurs, your sales approach helps you build barriers to competition and have long-term relationships with both individual contacts and their organizations. Sales success is a simple formula: make your Column 2 professional bonds with organizations as strong as your Column 1 personal ones with individual contacts to create long-term customers. Measurable and documented goals that you helped an organization to achieve become your "value-tether" to it even if your contact leaves and is replaced by someone who favors competitors.

You make goals measurable by making the customer's benefits measurable. The benefits of goals are similar to the benefits of features. Customers assign them value by the measurable value they produce. You convert their benefits into time or money also. You know this occurs if the word by appears in your benefit statement followed somewhere down the line by a dollar amount. A "by" will usually turn into a "buy."

Example

"Reduce costs by $32,000" (measurable benefit) or "increase production capabilities by 18 percent to generate seventy thousand (measurable benefits) more widgets weekly." You still need to know how much each widget generates in profit or sales dollars. Therefore, convert time or percentages to dollars too.

| Note | Goals without measurable benefits to new prospects are like hearsay to a jury; goals with measurable benefits are like evidence. Measurable benefits turned verbal references dependent on one customer knowing another into powerful documented dollar savings ones that only depend on the facts. |

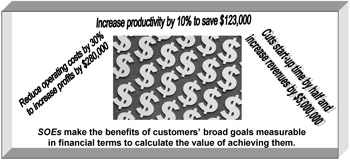

If you or customers leave out the measurable benefits of goals, they attract look-alike competitors. For instance, if customers are looking to improve efficiency, me-too competitors will claim that they too can improve efficiency. The only way to differentiate customers' goals is through their measurable benefits. One way to make the goal of improving efficiency measurable is to add the phrase "by reducing $100,000 of redundant production costs" to it. Now, me-too competitors must compete against this benefit's measurable benchmark of $100,000 worth of savings. (See Exhibit 3-5.)

Exhibit 3-5: Use SOEs to make customer's goals measurable.

| Note | When you have products and services that provide measurable dollar savings, you are able to broaden the goals you can help customers achieve. |

Example

Mark James sells the outsourcing of services to colleges and universities. Outsourcing is a service where a company hires and manages the labor force to perform jobs such as janitorial, engineering, housekeeping, and food services more cost effectively than the existing work force (although, they will often hire many of the existing employees). This company has a proven track record of reducing an institution's labor costs by hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Mark calls Dr. Roberta Brown, the president of a university, and finds out that she wants to upgrade the campus computers over the next three years. Mark tells her that he can help her to achieve that goal.

How? If Mark can save the university money on its facility services, that money can go toward the upgrading of computers. By converting goals into measurable dollar benefits, Mark will be able to show Roberta how an outsourcing company helps her to upgrade computers. Think of how many new opportunities you can create when you sell measurable value.

Customers Who Equate Needs with Goals

You also deal with customers who have only specific needs and products in mind. A customer might think she is satisfying her specific needs and that buying those specific products are her goals. They are not. You know the type. "Just give me a price on what I need and I will call you if you get the job." This person is the boss and that is that. You need a lot of willpower not to throw out a price and duck—and wish her (and you) luck.

Resist the temptation. You do not want to react to her specific product requests without either of you knowing her measurable goals. The risks of unfulfilled expectations run high. What do you do?

With diplomacy, you stick to helping the customer to define her goals. Once defined, customers do not become defensive if you ask them to review how their proposed product choices achieve those goals. Leave your product recommendations out of these discussions; it is too self-serving and you lose credibility. You want the customer—on her own—to come to the same conclusion you have: She is making the wrong purchasing decisions and her goals will prove it.

When a customer compares her specific product needs against measurable goals, she comes to one of two conclusions. She either proves herself right and proceeds as planned or she starts looking at different alternatives. If you are in market segments where customers' goals match up to your unique strengths, they look at your alternatives. You now have a powerful force on your side; no one knowingly makes bad decisions, not even customers who prefer competitors.

Example

Harry, an extremely technical customer, walks into a computer store. True to form, he starts blurting out abbreviations such BIOS, SDRAM, LDAP, and the like. He needs to buy a math coprocessor, a 120-MB RAM video card, and sophisticated multimedia software to upgrade his computer. The initial urge of Joan, the salesperson, is to say, "How many do you want?"

Instead, Joan wants to build long-term business relationships and repeat business. She helps her customers achieve their goals on a consistent basis. Therefore, the question she asks is: "What are you trying to accomplish with these components?" Harry cannot help but feel that Joan has his best interests (goals) at heart. Harry explains that he wants to use these components to more quickly create video productions with stereo sound. Joan advises Harry that those types of applications consume a lot of memory. She recommends purchasing 500 MB of RAM to prevent his computer from crashing.

Joan probably could have sold him those components without knowing his goals. However, in doing so, she risks that a week later a frazzled customer returns complaining how the parts she sold him did not "work." His computer keeps crashing because of out-of-memory errors. He demands his money back and is never seen again.

Significant differences and outcomes exist between trying to satisfy needs and helping customers achieve their goals.

| Note | If Harry didn't know what he was trying to achieve (goals), Joan could have suggested some from a Market Profile sheet she developed. There are no "What do you mean, what do I mean?" questions with superstars. |

Determining Which Goals You Can Achieve

The only customers' goals you pursue are the ones your products achieve. Your potential goes up as the number of your features— especially unique strengths—that could achieve their goals goes up. Although you think about specific products in this planning stage, do not mention specific products to the customers until you find out their purchasing requirements. You will examine this topic in Chapter 4.

Market Profile sheets motivate you to think about goals in ways customers in specific market segments do. You think about which goals you would want to achieve if you shared their organizational characteristics and positions. For instance, what would be your goals if you were the vice president of manufacturing for a personal computer manufacturer? One of your main goals would probably be minimizing production downtime. You then think about which unique strengths or strongest features of your products best achieve those goals. In addition, which systems of evaluation will accurately reflect the achievement of customers' goals via your unique strengths?

The following five-step evaluation can help you to fill out your Market Profile sheets accurately:

-

Review your past sales successes to see which types of customers produce the most wins.

-

Determine which organizational characteristics they have in common.

-

Classify them as market segments.

-

Evaluate the top three sales in each market segment for the goals, measurable benefits, and systems of evaluation they used.

-

Review with your two top customers in each market segment what you think their goals, measurable benefits, and SOEs are. Solicit their feedback for additions, deletions, and modifications.

Using this process, you will also end up with references that have measurable dollar savings—and customers who understand why doing business with you is a smart and well-thought-out decision.

| Note | The Science of Sales Success's focus is on helping customers to achieve their predictable professional goals. Customers' personal goals, like spending more time with their families or becoming financially secure, have too many intangibles which make them unpredictable. In addition, customers usually reserve discussions about their personal goals for salespeople who earned their trust by helping them to achieve their measurable professional goals. Again, it helps if you understand how your contacts' performance is measured, which, in essence, helps to form their goals. |

Protecting Yourself Against Bust Cycles

When selecting which market segments to pursue, one final analysis—economic sensitivity—remains to be taken into account. Economic sensitivity is a measure of how a market segment (and the customers within it) will react to changing economic conditions. It includes the following three categories:

-

Cyclical. The market segment follows the general economy. If the economy is booming, so is the market segment. If the economy slows down, so does the market segment. Typically, market segments in the manufacturing sector are cyclical in nature. For example, in a strong economy, people buy new products to support growth and replace old ones rather than repair them.

-

Countercyclical. The market segment goes in the opposite direction to the general economy. If the economy is booming, the market segment slows down. If the economy slows down, the market segment grows. Typically, market segments in the service sector are countercyclical in nature. A weak economy means people repair products rather than replace old ones.

-

Noncyclical. The market segment includes companies with both manufacturing and service business units. Therefore, these market segments will redirect their investments (that is, sales opportunities) depending on the direction and condition of the economy.

The key to consistency is to make sure you balance your market segment so value-driven and profitable sales opportunities exist during all three economic conditions.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 170

- Using SQL Data Manipulation Language (DML) to Insert and Manipulate Data Within SQL Tables

- Creating Indexes for Fast Data Retrieval

- Working with SQL JOIN Statements and Other Multiple-table Queries

- Writing External Applications to Query and Manipulate Database Data

- Retrieving and Manipulating Data Through Cursors