Firearms

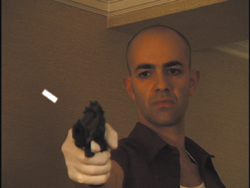

Re-creating gunplay is relatively straightforward via compositing. There are two basic types of shots to be outlined here: the firing of a gun and the result of bullet hits in the scene. The former can be done entirely with compositing. For the latter, compositing can do the trick in simple cases, but more active scenes of mayhem usually require practical elements on set. I'll discuss both cases, so that the independent filmmakers among you are prepared for either scenario. There's probably a scene out there, quite possibly from one of your favorite movies, that contains reference very similar to what you're trying to do. As you prepare to stage these effects, I encourage you to carefully study, frame by frame and loop after loop, similar sequences that you like. Firing the GunSometimes it can be difficult for actors to work on set without practical effects. The firing of a handgun, however, shouldn't be any problem. A prop gun still clicks when you pull the trigger, and the actor need only mime the motion of the recoil, or kick. The kick is minor with small handguns, but a much bigger deal for shotguns; again, this is something you can check with reference. So that's how you start, with a shot of an actor pulling the trigger and miming the kick (Figure 14.1). From there, you typically add just a few basic elements via compositing:

Figure 14.1. Just by virtue of pulling the trigger on the prop handgun, the actor creates enough motion to set the anticipation of the ensuing muzzle flash to be overlaid. (Image courtesy of The Orphanage.)

The actual travel of the bullet out of the barrel is not something you have to worry about; at roughly one kilometer per second, it is generally moving too fast to see amid all the other effects. The bullet is usually evident more by what it causes to happen when it hits something, which I'll get to in the next section. Muzzle Flash and SmokeThe clearest indication that a gun has gone off is the flash of light around the muzzle, at the end of the barrel. This small, bright explosion of gunpowder typically lasts only one frame per shot (a repeating firearm is just a series of disconnected single frame flashes), and it can be painted by hand, cloned in from a practical image, or composited from stock reference (Figure 14.2). Figure 14.2. The angle of the shot and the type of gun affect the muzzle flash effect. The first image is from an M16 rifle; the other is from a handgun. (Images courtesy of Artbeats.)

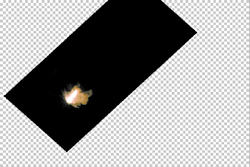

Figure 14.3 shows the addition of a single-frame muzzle flash for the firing of a handgun. Because it is in close-up, the flash obscures much of the frame. It is a mixture of flash and smoke matted in from a pyrotechnic reference shot. All that is really required for this single shot is a single-frame overlay; there's no need to carefully dissipate the smoke to make the shot believable. Figure 14.3. For this close-up of a muzzle flash and smoke added to the plate from Figure 14.1, only a single frame of smoke was blended in from a photographed source, likely with Add mode. (Image courtesy of The Orphanage.)

Contrast that with Figure 14.4, which shows a Gatling gun fired from a helicopter. Clearly, this scene has a lot more going on in it than just muzzle flash and smoke. Because it's a repeating gun, the flashes occur on successive frames and the smoke builds up along with debris caused by bullet impacts. The way the shape of the muzzle flash varies over time as well as its relative size and placement were the keys to the shot, and they required the study of reference. Figure 14.4. The fiery muzzle flash of a Gatling gun has a characteristic teardrop profile shape; here it was painted in from fire source. (Image courtesy of The Orphanage.)

The shape of the muzzle flash depends on the type of gun being fired, and just as with lens flares and other equipment-specific visual elements, you are heavily encouraged to find a movie that has your gun in it. You can also consult the NRA-ILA Web site (www.nraila.org) to learn how the color and amount of smoke depends on the type of gunpowder. Typically, there is an explosion traveling in two directions from the end of the barrel: arrayed outward from the firing point and in a straight line out from the barrel. Find smoke, explosion, or fire source, and you can clone in your own on a separate layer, then apply it with a blending mode (typically Add). With automatic weaponry you may have your work cut out for you painting frame by frame, but with good reference to reassure you, this can be quick and dirty work. If you have a budget to purchase stock footage, you can look for one that contains muzzle flashes (such as the Artbeats Gun Stock collection, www.artbeats.com); these are shot over blue or black, ready to be matted, blended, or painted into your shot. Shells and Interactive LightIf the gun in your scene calls for it, you can add that extra little bit of realism with a secondary animation of a shell popping off the top of a semi-automatic. Figure 14.5 shows just such an element in action. All you need is a four-point mask of a white solid, animated and motion blurred (Figure 14.6). You don't have to worry about the color; instead adjust the element's Opacity to blend it into the scene. Figure 14.5. A shell pops off of the fired handgun. Note that the shell appears only as a blurred, elongated white element in frame with no discernable detail. A blue-screen shot of an automatic weapon shows a much more discernable shell. (Images courtesy of The Orphanage and Artbeats.)

Figure 14.6. All that is required to transform a four-point masked white solid to a shell popping off the gun is heavy motion blur and a sufficiently low Opacity setting. (Images courtesy of The Orphanage.)

Depending on the situation, don't forget that the bright flash of the muzzle might also cause just a brief flash on objects near the gun, especially on the subject firing it. From tips in Chapter 12, "Working with Light," you should know what to do: Softly mask in a highlight area, probably using an adjustment layer with a Levels effect or a colored solid with a suitable blending mode. The keys are recognizing that the adjustment is necessary in your particular shot and to what extent. As a general rule, the lower the ambient light and the larger the weapon, the greater the likelihood of interactive lighting. A literal "shot in the dark" would illuminate the face of whomever (or whatever) fired it, just for a single frame. This is a great dramatic effect, but one that is very difficult to re-create after the fact if you didn't plan for it. If your shot was taken in low light, you will lack any details to illuminate. This is one of those cases where firing blanks on set might actually be called for, assuming the continuity of action in the shot is too visible to be faked by dropping in a single-frame still of the brightly lit assassin. Bullet HitsBullet hits on set are known as squib hits because they make use of squibs, small explosives with about the power of a firecracker that go off during the take. Sometimes squibs are actual firecrackers. Under some circumstances, it is possible to add bullet hits without using explosives on set, but with enough gunplay going on, you will probably need a mixture of on-set action (not necessarily actual squibs) and post-production wizardry. Figure 14.7 shows a before-and-after shot adding a bullet hit purely in After Effects. In this case, the bullet is causing no collateral damage, but it is embedded directly into a solid metal object, namely the truck. In such a case, all you need to do is to paint the results of the damage on a separate layer at the frame where the bullet hits. Then, if necessary, you can motion track that layer to marry it solidly to the background frame (Figure 14.8). Figure 14.7. This sequence of frames shows a second bullet hitting the cab of the truck, using two elements: the painted bullet hit and the spark element, whose source was shot on black and added via Screen mode. (Images courtesy of markandmatty.com.)

Figure 14.8. The bullet hit is where you get to become a little bit of a matte painter. The example shows a bullet hole in metal, which has a fairly consistent look. If the bullet were to hit a door frame, you'd need to add irregular splintered wood. One frame is all that's ever requiredmayhem happens quickly. Here, the result has been motion tracked to match the source background plate. (Images courtesy of markandmatty.com.) At the frame of impact and for a frame or two thereafter, you usually need to add a shooting spark and possibly a bit of smoke (if the target is combustiblenot in the case of a steel vehicle) to convey the full violence of the bullets. As with the muzzle flash, this could be just a single frame, or it can be a more fireworks-like shower of sparks tracked in over a few frames (Figure 14.9). For the more elaborate case, you may want to composite in an element shot separately. Figure 14.9. You can add the source spark element using Add or Screen blending mode, dropping out all of the black background. (Images courtesy of markandmatty.com.)

To create an element of a bullet hit, you can set up a little miniature effects shoot using a fire-retardant black background (a flat, black card might do it) and some firecrackers (assuming you can get them). The resulting flash, sparks, and smoke stand out against the black, which you can remove either using a blending mode that removes black (such as Add or Screen) or with the addition of a hi-con matte (Chapter 6, "Color Keying"). Or if dangerous explosives aren't your thing even in a controlled situation, there is stock footage available. Figure 14.10 shows a before-and-after shot of a scene in which a lot of extra debris had to fly around in addition to the bullets to make the shot believable; the character's apartment was being strafed by the helicopter. Compositing in this debris after the shot was taken would be highly inconvenient, causing an impractical amount of extra work compared with firing a BB gun at items on the set and enhancing the effect with sparks and smoke in After Effects. Figure 14.10. A BB gun was aimed at various breakaway objects on location and assistants hurled other small objects into the scene to add the necessary amount of debris on location. This has to do with compositing only as a reminder that you should try to get action on set when you can, particularly if you're making your own film. Practical debris is very difficult to add after the fact. (Images courtesy of The Orphanage.)

So to recap, a good bullet hit should include

Later in this chapter, you'll learn how much explosions have in common with bullet hits, which are essentially just miniature explosions. In both cases, a bit of practical debris can be the key to believability. |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 156