6.3 Financial Reform and Corporate Governance in China

|

6.3 Financial Reform and Corporate Governance in China

Erika Leung, Lily Liu, Lu Shen, Kevin Taback, and Leo Wang

With the potential to develop into an economic superpower, China has undertaken the enormous task of developing market-based institutions. Confidence among market players is central to the market economy. Corporate governance provides an important framework to support this confidence. In fact, China's most prominent regulator in the drive to create efficient markets, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), has declared 2002 the year of good corporate governance.

Corporate governance is a broad subject, intertwined with many areas of financial reform. The western concept of corporate governance has been codified by the OECD. The concept centers on the following principles: transparency, accountability, and fairness. The main mechanisms to look for include an independent board of directors, treatment of minority shareholders, and coordination of the interests of capital owners and business managers.

In its development of corporate governance, China will try to avoid financial crises and plundering of state assets. Retaining capital, fostering domestic investments, and raising badly needed cash to fund social obligations are recurring policy themes.

As China develops its markets and institutions, it enjoys the learning advantage of a late mover. It can take best practices from other economies and avoid major pitfalls. China's challenge is to develop its rules and institutions in a very compressed timeframe and create lasting markets.

Financial market development and reform in China started as a byproduct of the state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform. However, as China's economy takes off, the role of the financial market becomes much more important to the growth of the economy. Some call corporate governance the "last pillar to be moved" in China's economy.

Financial market development and better corporate governance have become entwined.

This paper addresses some important issues in corporate governance and financial market reform in China. The first two sections provide an overview of China's securities market and discuss a range of problems arising from the securities market development. The significant hurdles China must overcome include:

-

the legacy of a quota-based, politically driven listing process

-

the role of the CSRC (China's SEC)

-

the development of a liquid market with institutional investors

-

the ability of companies to bypass domestic markets by seeking financing abroad

The third section examines issues arising from listing SOEs on China's stock exchanges and diluting state ownership. The questions we address here are: Does listing of SOEs really improve corporate governance? Are initial public offerings of SOEs sufficient, or should the state significantly dilute its ownership in SOEs to improve corporate governance? Finally, does better financial performance follow from listing?

In the last section, we examine the connection between nonperforming loans (NPLs), banking sector reform, and corporate governance. Specifically, how successfully will Chinese banks deal with NPLs? How fast can the Chinese government further deregulate the banking industry?

China's Financial Sector: Development Overview

A well-developed financial market is one of the crucial elements of corporate governance reform. In this section, we provide an overview of the current Chinese financial market by focusing on the securities and banking sectors.

Rationale for Forming the Securities Market

The securities market can be viewed as a first step toward creating domestic capital markets. The securities market can also be a tool through which the government can shift some of its SOE responsibilities to economic forces. In 1990 and 1991, the government set up the Shenzhen and Shanghai securities exchanges, respectively, as an experiment in installing a capital market apparatus in China.

The securities market has enjoyed much growth over the past ten years. Since 1995, equity market capitalization has risen to RMB5 trillion, or 400 percent (CSRC, 2000). Over 1,000 companies have listed between the two stock exchanges, with coverage expanding from a mainly local base to an extended national base.

While the exchanges enjoyed relatively high levels of autonomy in the first few years of operation, the combination of the extended coverage and the Asian financial crisis led the central government to tighten its control. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) was created and became a governing body that answered only to the State Council. Regulatory enforcement thus became more centralized and local governments played a much less active role in formulating regulations and policy about the further development of the capital market.

Makeup of the Ownership Structure

The initial listings of public companies were politically driven. Some SOEs were performing poorly, and the securities market became an easy venue for companies to generate funding from the public and create some independence from political influence. A system of quotas was established by the central regulators and administered in the provinces. Each province was given a number of SOEs that could be listed, and it was up to local leadership to determine which firms it would list. Certain performance requirements had to be met, but the process was full of political pitfalls, with little resemblance to market forces.

In theory, consideration of SOEs for listing should be in the order of their financial health, that is, the best SOEs get listed first. However, the reality was that provincial governments used scarce quotas for companies who needed money the most. Because the listing law specified that a company had to show three years of continued profits to qualify for listing—a law that was borrowed from Hong Kong—provincial governments often bundled companies that had profits with poorly managed companies that needed money. As a result, companies with no apparent synergies were bundled together. In some cases, the managements of companies that got bundled together did not know each other until just before going public (Neoh, 2002). An example of bundling companies is given in box 6.3.1.

Changhong Enterprise in Sichuan province, a television producer who had little access to large-scale state financing, managed to be successful in leveraging foreign technology and optimizing human resources within the enterprise. Further, it developed the market by establishing a comprehensive distribution network and a complete after-sales service. In 1998, Changhong's annual turnover of $2 billion was impressive and supported the locality's tax revenues.

Although an example of successful SOE strategy, Changhong is also an example of a contemporary whose success brought it responsibilities as part of a centrally planned economy. Changhong was asked to take over other less profitable—or at times simply unprofitable—SOEs. Even before the listing, Changhong was approached by the regulatory authorities to assume responsibilities for several SOEs in Nantong and Changchun. Although there is some vertical integration benefit inherent in the acquisition, the primary rationale was to balance the books so that the integrated SOE would appear to be more profitable than it actually was.

The ownership structure of listed companies is distinctively Chinese. Shares of the listed companies are classified into three categories: state shares, legal-person shares, and tradable shares.[1]

State shares are held by central and local governments or by statedesignated institutions (including SOEs). These shares cannot be publicly traded without the explicit approval of the state. While the exact definition is not clear, the "state" includes the local financial bureaus, state asset management companies, or investment companies. Sometimes the parent of the listed company, itself an SOE, can be counted as "state." Usually, the state comprises the controlling shareholders in publicly traded companies.

Legal-person shares are held by domestic institutions, including industrial enterprises, securities companies, real estate development companies, foundations, research institutes, and any other economic entities with legal-person status. A "legal person" is defined as a nonindividual legal entity or institution, but in effect they are just a nominal distinction from state entities. The only distinguishing difference for legal persons may be the hierarchical differentiation between central and local governments. Most important, the legal-person shares are not publicly tradable, and they are subject to the same restrictions as state shares. Last, the legal-person shares are categorized by their ownership structure into SOEs, SONPO (State-Owned Non-Profit Organizations), collective enterprises, private companies, joint-stock companies, and foreign-funded companies.

Tradable shares are offered to—and are freely tradable in—the securities market. These shares are mainly held by individuals, and they provide the real liquidity in the securities market (where state shares represent 37 percent, legal-person shares 28 percent, and tradable shares 35 percent). The individual shares are also known as A-shares, held solely by Chinese citizens in domestic currency. There are also Bshares, which are domestically listed, foreign-held shares available only to foreigners. While the government tried to maintain a strict partition between the two markets,[2] recent trends suggest that there will be further integration of the different classes of shares in the Chinese market.

China's Entry into the WTO

While many believed that China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) signified the end of its reform agenda, it has, on the contrary, just begun. Laura Cha, vice chairman of the CSRC, comments: "For all levels of the Chinese government, the work has just begun," and in fact, entry to the WTO has "galvanized reform efforts."

Under the current agreement, foreign securities firms can establish joint ventures—with foreign ownership less than one-third—to engage in underwriting A-shares, and in underwriting and trading Band H-shares,[3] as well as government and corporate debt without a Chinese intermediary within three years of accession to the WTO. Furthermore, foreign insurance companies will also be allowed to operate in China, creating the foundation for institutional investors.

Commercial banking reform will also be accelerated under WTO. Currently, foreign banks lack the distribution network of domestic banks, and domestic banks lack sophisticated products and operational systems. Enabling further domestic and foreign competition, and offering more products to domestic customers, will pose great opportunities and threats for the domestic banking industry.

Banking Industry Overview

Because bank loans are still the most dominant source of financing for domestic companies, the banking industry plays a key role in shaping economic development in China. With the various deregulations in the banking industry, more shareholding and private banks have entered into the picture, offering more products and services. After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, three commercial banks merged into the central bank, which dominated all of China's banking services. Driven by the need to reform the SOEs, the banking sector started undergoing reforms in 1978. The most important reorganizations have been to separate policy banks and commercial banks from the central bank. By 1999, there were four state commercial banks, five national commercial banks, 12 regional commercial banks, and two housing savings banks. In addition, there were 274 foreign bank representative offices, 163 foreign bank branches, six foreign banks, and seven joint-venture banks, engaging mainly in trade-related finance and non-RMB business. Figure 6.3.1 depicts the current players in Mainland China's banking industry and outlines its historical development.

Figure 6.3.1: Banking structure in China.

Inefficiencies in the state-run banking system led to the creation of a significant nonperforming loan (NPL) problem for the country. The size of the NPL problem is in the range of half a trillion RMB (US$518 billion), or more than 40 percent of total loans outstanding—almost half of China's GDP. To deal with the NPL problem, China established Asset Management Companies (AMCs) in an effort to deal with selling assets of debtor companies, recovering amounts owed, or writing off uncollectible debts.

Emerging Problems in Developing Mainland China's Securities Market

The development of the securities market in China has not been smooth. While the establishment and the continual metamorphosis of the securities market have caused some academics to applaud, we believe that the inherent problems that are identified in the securities market reflect more systemic deficiencies within the Chinese financial infrastructure. In this section, we will delve into some of the more pertinent problems that we feel are key to a successful financial market transition.

Listing Process

As suggested in the previous section, the selection process for listing companies has historically been highly political. The Chinese stock market gained a reputation as a place to get free money for enterprises. The central government gave priorities to certain SOEs, and while minimum standards provided for the screening process, the actual procedure of getting listed fell to the level of favoritism, misinformation, and bribery.

First, the quota system and provincial recommendation format encouraged bribery on the local government level. The listings were based on recommendations from the local government, and since local officials were the gatekeepers to the stock market, they became obvious targets for corruption. Once the officials were successfully lured into a deal, the overwhelming incentive was to make the company in question as attractive as possible. As a result, rampant corruption, false documentation, and convoluted selection processes led to the overall disappointing performance of the listed companies.

Second, the state regulated the types of share issues and their liquidity. The state owns nearly two-thirds of the shares issued. These shares consist of two types, state-owned shares and legal-person shares. Both are nonliquid and not publicly tradable. As a result, state ownership significantly reduces the liquidity and financial disciplinary role of the stock market. Only shares belonging to individual investors are freely tradable, leaving two-thirds of the equity market illiquid and not exposed to financial discipline.

Recently, the CSRC initiated significant changes in the listing selection process. The changes reduced the role which local government plays, but the effectiveness of the new procedures still remains to be seen. Box 6.3.2 provides typical examples of corruption in the listing and investing process.

Listing-Related Corruption

Since a public listing is a limited commodity and the listing itself implied ‘free money’ from individual investors, enterprises go through all venues to try to guarantee their positioning for the next listing. The types of corruption extend from falsification of company financial information to the blind support of high government officials on all levels—from municipalities to city, provincial, and state levels. A typical example of this nature is the case of Kangsai Group, formerly known as the Huangshi Garment Factory in Hubei province, where the extent of the bribery system proved to be staggering.

From 1993 to 1996, prior to the company's listing, Kangsai's management offered discounted internal shares to more than 100 officials who were deemed useful during the listing process. The shares were offered to the officials at RMB1.00 per share, about one-sixth of the pre-listing value. When the group gained listing rights, the value went as high as RMB30.00 per share, a comparable return to the Internet start-ups during 1998. Among those who accepted these bribes were the vice minister of SETC (State Economics and Trade Commission) and the minister of MTI (Ministry of Textile). These two ministers are instrumental in making the listing of Kangsai a success, but it is also a sobering demonstration of the lack of integrity that is exemplary of an incomplete capital market.

Investing-Related Corruption

In 1992, the Shenzhen stock exchange experienced the first public protest of unequal opportunity given to individual investors. Since the stock exchange was still a new experiment, investors who were interested in getting in on the IPO investment had to first acquire an IPO application form, of which 10% would be awarded the right to subscribe. Following the announcement of the news, more than one million people waited in line to get their opportunity. Unfortunately, the distribution of the application was over before it hardly began, leaving the investors behind with the realization that these applications have already been allocated to the friends and family who got in through the back door.

Limited Role of the Governing Body—China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC)

In 1997, with the Asian financial crisis as the backdrop, CSRC was appointed as the sole overseer of the two exchanges in Shanghai and Shenzhen. This was a drastic departure from previous practices, because the local and municipal governments were in effect removed from the decision-making path. Further, with the passage of the Securities Law, the CSRC seemed to possess the dual power of overseeing and managing the securities market and of standardizing existing laws and regulations within a unified legal framework. In terms of the listing process, the CSRC reformed numerous aspects of the system. For example, the administrative approval system was revamped to abolish the right of local government to recommend stock listings. Instead, a set of listing criteria was set up and a central committee was created to review and evaluate the legitimacy of the potential listing companies. As compared to the CSRC's record of rejections under the local recommendation scheme, the record following the passage of the Securities Law was much more impressive—40 percent of applications have been rejected. Furthermore, the CSRC is currently promoting the use of internationally accredited law and accounting firms for the duediligence process for potential listing firms. This, coupled with the demands of the WTO entry, seems to be promising for the establishment of a credible monitoring and enforcement system in the securities market.

In delivering new regulations, the CSRC has made an effort to improve compliance by reducing the discretion that companies have in interpreting laws. Templates have been provided for dealing with profit warnings, connected party transactions, ownership changes, and other important events. The Shanghai Stock Exchange now requires that companies issue warnings by January 30 if their profits will drop by more than 50 percent from the previous year or if they will report losses in the year.

According to statistics, the CSRC unveiled 51 laws and regulations from early 2001, when Laura Cha (the vice chair of the CSRC) first took office, to the end of the year. So far, the CSRC has established a basic framework of regulatory rules. During that period of time, more than 80 listed companies and 10 brokerages were publicly criticized, penalized according to administrative rules, and even put under judicial investigation (Hu et al., 2002). The CSRC has also delisted three companies and revoked the securities licenses of five local accounting firms that had been involved in the improper preparation of listed-company financial reports.

However, academics are at times skeptical of the long-term effectiveness of the CSRC. In terms of enforcement, new cases of delisting and other crackdowns seem to have subsided. While the establishment of a coherent regulatory framework and the continued disincentivization of corruption in the listing process is commendable, the real power that the CSRC holds—in enforcing the regulations and acting as a governing body independent of the central government—is in serious question.

Independent Directors

Although listed companies do have independent directors, these directors often do not fully understand their responsibilities. In the United States and other developed countries, directors are brought in when they have extensive knowledge of the industry, of financial markets, or of the legal system—all of which are relevant to the listed company. These directors are either active advisors or they act as independent checks and balances for the overall health of the company.

"There are strict stipulations internationally on the qualifications of independent directors. Some emphasize accounting experience and some emphasize knowledge in law. But whatever aspect is emphasized, there is one common point: that is, the independent directors should have a certain professional background. For example, the U.S. National Association of Securities Dealers requires that an independent director should be able to understand the company's financial statement and the issuer should make sure that the auditing committee has at least one member with the professional background of financial accounting, who should be well versed in corporate accounting and disclosure of financial information." (Hu et al., 2002)

Although the recent Enron case proves that even in the United States directors do not always fulfill their duties, China is still far behind in the basic understanding of the role that independent directors play.

China is also behind on the manpower required for the future needs of the listed companies. In August 2001, the CSRC issued detailed guidelines regarding independent directors, mandating that companies have three independent board members by 2003 and including strict board meeting attendance requirements. A sample of all 314 directors listed at 204 listed companies showed that nearly half were university academics (The Chinese Entrepreneurs Magazine; Zhang, 2002b). With 1,000 listed companies, this means there will be a need for at least 3,000 independent board members next year. The short supply of qualified directors will continue to be a challenge for companies needing to meet the CSRC's requirements.

Liquidity in the Marketplace

The tradability of stocks is one of the frequently discussed areas of the Chinese securities market. As mentioned in the previous section, tradable shares only account for about one-third of all shares, and the inferred liquidity of the Chinese capital market is only about 40 percent of the total market capitalization. Although the turnover ratio is 550 percent for tradable shares (Neoh, 2002), the highly volatile market suggests that the high turnover ratio is a product of the speculative nature of the market, rather than of a well-developed liquid market. Moreover, because of the lack of depth in the market, the stock market is also prone to manipulations.

Sophistication of Investors

Chinese investors are for the most part unsophisticated. They operate on a hearsay basis and are usually in the market for short-term gains. In China, large-cap stocks account for a very small fraction of total market turnover (Neoh, 2002). In more developed and less speculative markets, large-cap stocks usually account for a larger percentage of turnover, and investors maintain a longer investment horizon.

Retail Investors

Retail investors, individually, have no means or intention to exercise any influence over the companies in which they hold shares (Zhang, 2002b). Historically, having strong returns in the market makes people less interested in fundamentals and governance than in speculative stock returns. This is not surprising, since many of the investors that have the time to gamble in the stock market are retirees.

Another example of investors' lack of concern for company fundamentals and corporate governance is the case of ST-labeled companies. When listed companies have accounting losses for three years in a row, exchange regulations require "ST" to be placed in front of the company name. Zhang (2002b) points out that retail investors flock to ST shares despite their poor financial results, because investors know that a form of bailout will be in the works. Parent companies have been skilled at creating success stories through financial engineering and restructuring to prevent further losses. Of the seven examples listed in table 6.3.1, all were renamed and reengineered through debt restructuring and selling assets. The mechanism Zhang cites is that parent companies and local governments will buy assets at artificially high prices to generate profits for the listed companies.

| Code | Original name | New name | How they succeeded |

|---|---|---|---|

| | |||

| 0004.SZ | ST Shenzhen Anda | Beida High-tech | Debt restructuring, selling assets |

| 0038.SZ | ST Shenzhen Dalong | Shenzen Dalong | As above |

| 0502.SZ | ST Qiong Energy | Qiong Energy | As above |

| 0550.SZ | ST Jiangling | Jianling Motors | As above |

| 0555.SZ | ST Qian Kaidi | Taiguang Telecom | As above |

| 600137.SS | ST Packaging | Chang River Packaging | As above |

| 600696.SS | ST Haoshen | Fujian Haoshen | As above |

| Source: UBS Warburg, China Securities News | |||

Institutional Investors

Data compiled at the end of 2000 show that the capitalization of the U.S. stock market stood at U.S.$17.2 trillion, of which individual investors accounted for $6.6 trillion, or 38 percent, and institutional investors $10.6 trillion, or 62 percent. Clearly, institutional investors (including mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies) dominate the U.S. stock market and are critical for a well-functioning market. But things are different in China.

By the end of 2001, proprietary trading and investment in the funds by securities companies accounted for less than 10 percent of the capitalization of the negotiable shares in China's stock market, indicating that institutional investors are still a weak group in China.

The presence of institutional investors has a stabilizing effect on the securities market because institutional investors make long-term investments in specific stocks, with less portfolio turnover. Moreover, institutional investors with a large stake in a particular company could exercise powerful influence over corporate governance in those companies. Although there is evidence that institutional investors in emerging markets tend to adopt a shorter-term investment perspective,[4] a stronger presence of institutional investors will benefit the Chinese securities market (Zhang, 2002b).

Raising Capital Overseas—The Hong Kong Securities Market

Beyond the mainland domestic market, Chinese enterprises can raise capital through the Hong Kong securities market. As of May 2001, among the 55 mainland enterprises that had sought overseas listings, 54 of them listed in Hong Kong, raising an accumulated capital of HK$124 billion (US$16 billion).[5] Kwong Ki-Chi, chief executive of Hong Kong Exchange and Clearing Limited, has stated that with China's entry into the World Trade Organization, "many mainland enterprises will need to raise funds to strengthen themselves in preparation for competition with foreign firms," thus increasing "the demand for mainland companies to raise funds in the SAR (Hong Kong) market."

With a very active market and the strong presence of institutional investors, the Hong Kong securities market provides an attractive avenue for Chinese companies to raise capital beyond the domestic market.[6] However, listing in Hong Kong is subject to strict listing and disclosure rules, and only a handful of Chinese companies could realistically list on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE). The recent failure of the Bank of China's attempt to list its Hong Kong branch on the Hong Kong and New York Stock Exchanges is a case in point. Nonetheless, the hope of gaining access to international capital and deeper pockets could accelerate the current reform efforts.

Will Shanghai Take Over Hong Kong as China's Financial Center?

With China rapidly developing its securities market and tightening its regulations, many people feel that it is inevitable that the domestic market—especially Shanghai, with its close proximity to Beijing—will one day take over Hong Kong as China's premier financial market. According to a recent (2002) report in the Economist, if Shanghai continues to grow at the rate of the past decade, its GDP "will match Hong Kong's in 15 years." In addition, Shanghai enjoys a range of advantages over Hong Kong, including close political ties to Beijing, access to relatively cheap and well-educated mainland labor, and substantial government spending on infrastructure. However, as the article also points out, Shanghai's close ties to Beijing are also its main disadvantage. Entangled with mainland China's murky political system, Shanghai's property market and financial system are "ill-regulated and chaotic," and its legal system is "arbitrary." Shanghai's skyline might rival that of any financial center in the world. But to become an international financial center, China has to build confidence and credibility, not more skyscrapers.

HKSE chief executive Kwong Ki-chi said he was not unduly concerned by the possibility of mainland companies listing on the domestic markets in Shanghai or Shenzhen instead of Hong Kong: "For the companies which want to raise funds in Hong Kong dollars or for those which want to have a wider access to international investors, Hong Kong will be their first choice," he said.

(Lowtax.net 2002)

The Issues to Watch

China's ability to overcome its legacy of listed companies (companies brought to market through a political process) will be critical to the proper development of its markets. The CSRC will continue to play a pivotal role in developing market mechanisms, and its power will be sufficiently tested by all those affected. Without strong demand for liquidity and stability, efforts to reform securities markets will have little support. And finally, should China's market developments stall further, the best domestic companies will have alternative sources of financing.

SOE Listing and State Share Sales

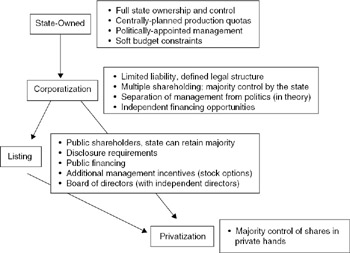

Reforming China's state-owned enterprise (SOE) sector is at the core of China's economic reform. Since the reform started in the late 1970s, significant progress has been made in such areas as accounting standards, reporting, and reorganizations. Indeed, the need to reform the SOEs has been the most important driver of reform in the financial market. After twenty years, it is recognized that SOE reform has fallen short of the standards set by efficiently operating businesses in developed economies. The core of the problem lies in the difficult tasks of reforming the SOE ownership structure and improving corporate governance. In this section, we focus on the corporatization of SOEs and their subsequent listing—two major steps in ownership reform. Figure 6.3.2 illustrates the relationship between corporatization, listing, and privatization of SOEs.

Figure 6.3.2: Corporatization and privatization in China.

Corporatization of SOEs to Clarify Property Rights and Improve Performance

Corporatization (gongsihua) of SOEs started in 1992 as a way of clarifying property rights of SOEs and improving their performance. After serious attempts to improve SOE performance through increased autonomy failed, it was recognized that the crux of poor SOE performance was the ambiguity of property rights inherent in state ownership. Ownership by "the whole people is almost equivalent to free goods, since nobody owns it" (Nakagane, 2000). The corporatization program sought to solve the problem by converting SOEs into Westernstyle corporate entities with more clearly defined ownership structures, such as joint stock companies (JSCs) and limited liability companies (LLCs).

There were political as well as economic considerations behind the corporatization program. Politically, corporatization was a way to reduce state intervention and improve corporate governance of SOEs without full privatization. By reallocating formal control rights from a single controlling entity to a small number of state institutions and SOEs, the state hoped the resulting multiplicity of shareholding would sever the link between an SOE and its controlling authority. The company would be subject to the checks and balances of a small number of owners. Thus, it would, we hope, become immune to excessive political interventions and only operate on economic objectives.

Economically, corporatization was to increase SOEs' access to funds beyond traditional bank loans and state subsidies, such as the vast amount of household savings. It was also to separate state ownership from the management of SOEs, and to hold company directors responsible for the assets of the company and prevent further asset theft.

Listing of SOEs to Mitigate the Agency Problem and Increase Transparency

Concurrently with the corporatization process, SOEs were given increased autonomy in management and operations. Corporatization separated the management of SOEs (agent) from its ultimate control (principal), creating an agency problem. In this context, increasing management autonomy without aligning incentives exacerbated the agency problem. Company management often acted in its own interests, stripping off company assets for personal gains. As a result, corporate performance further deteriorated, necessitating other remedies. This motivated the listing of SOEs on domestic stock exchanges, with sale of shares to private investors. It was hoped that the increased transparency and incorporation of private ownership interests through listing would provide the checks and balances on management to improve performance.

The questions we want to address here are: Does listing of SOEs really improve corporate governance? Is initial public offering of SOEs sufficient, or should the state significantly dilute its ownership in SOEs to improve corporate governance? Finally, does better financial performance follow from listing?

In principle, the listing of SOEs should ultimately create better management incentives with more objective performance feedback structures in the form of stock performance. Introducing apolitical shareholders with board representation that seeks to maximize firm values should improve monitoring and should mitigate informational asymmetries. It also imposes a more standardized set of disclosures that increase transparency. Furthermore, raising equity capital helps reduce debt loads and frees resources for investment. Finally, empowering employees through ownership also helps align interests with management and shareholders.

In practice, the story is a mixed one. As noted earlier, corporatization was a way of avoiding full privatization. With listing, an attempt is made to provide independence and structure to the corporatized SOE, but ultimate control (through ownership) is not fully transferred from the state. Only a small share of the equity in an SOE is listed in an IPO and sold to private investors. In fact, the state retains two-thirds ownership (through state and legal-person shares) in most listed companies, ensuring no substantive change in the nature of ownership and control by the state. The presence of outside shareholders and additional public disclosure requirements due to listing do, however, ensure more transparency and arguably better governance.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that transparency is only as good as the credibility of management, board members, and auditors. Investors will have a hard time acting on information just because it is disclosed—it has to be believable and predictable. Furthermore, liquidity and efficient markets are critical for such disclosure to have any value. China's market has not developed sufficiently—and regulatory compliance is not complete enough—to provide a clear link between performance, stock prices, and oversight of listed companies.

Effects of Listing—Discouraging Empirical Evidence

Empirical evidence on the effects of listing SOEs is discouraging. Wang, Xu, and Zhu have performed a compelling statistical analysis of listed SOEs from 1990 to 2000 (Wang, Xu, and Zhu, 2001). They found that the financial performance of SOEs deteriorated after listing. Measured in terms of return on sales and return on assets, post-IPO performance of listed SOEs trends worse than results in the periods leading up to IPO. Table 6.3.2 shows the average return on assets (ROA) drops steadily, from 19.6 percent in the year immediately prior to IPO to 2.7 percent in the sixth year after IPO. The average return on sales (ROS) also decreases, from 16.6 percent one year before listing to 0.2 percent in the sixth year after listing. In addition, capital expenditures as a percent of total assets declined rapidly after listing. However, Wang et al. did find that performance is positively correlated with a more balanced ownership structure among top shareholders, suggesting that less concentration of power in a single shareholder's hands leads to better performance. In the sample studied, all the firms were listed under the quota system that has since been phased out.

| Year –1 | Year 0 (IPO) | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||

| ROA | 19.6% | 15.4% | 9.7% | 7.4% | 2.7% |

| ROS | 16.6 | 16.2 | 13.7 | 7.8 | 0.2 |

| Capex/Assets | 74.3 | 57.7 | 43.1 | 28.2 | 3.8 |

| Annual sales growth | 28.7 | 47.8 | 22.2 | 10.5 | 16.5 |

| | |||||

| Source: Wang, Xu, and Zhu (2001), World Bank | |||||

Zhang also notes that post-IPO performance of many firms is disturbing. Of the 90 companies that went public in 1999, only 25 met forecasts disclosed in their prospectuses. Of the 25 that met forecasts, 11 did it through financial engineering (asset sales and restructuring). The most egregious examples include Changjiu missing its forecast by 75 percent, Hualin Tyre being 66 percent short, and China Agricultural Resources issuing profit warnings within six months of its IPO (Zhang, 2002b).

Wang et al. present traditional explanations of this evidence that center on "window dressing" or inflating pre-IPO performance to ensure successful IPOs. In addition, they argue that lack of ownership by management and dispersion of shareholders do not create the necessary incentives for performance (Wang, Xu and Zhu, 2001).

Zhang suggests additional sources for poor performance stemming from a lack of corporate governance. These problems are in the area of connected-party transactions and loans from listed companies to their state-owned parents. The relationships between listed subsidiaries and parent companies are fraught with governance problems and pose a major hurdle to better performance. Zhang cites the case of Luoyang Chundu going bankrupt because its parent owed it RMB330 million since Luoyang Chundu's IPO in 1998, which was 80 percent of its IPO proceeds (China Securities News; Zhang, 2002b).

The CSRC issued a set of guidelines in June 2000 called "Announcements Regarding Listed Companies' Loan Guarantees for Others," which prohibits related-party loans and loan guarantees. Yet a year later, New Fortune reported 159 new loans disclosed in 2001, which amounted to RMB 23.1 billion. (See table 6.3.3).

| Company | Guaranteed amount (Rmb m) | Guaranteed amounts/Equity |

|---|---|---|

| | ||

| Founder Technology (600601.SS) | 465 | 82% |

| Lujiazhui (600663.SS) | 1,962 | 46% |

| Xinye Property (600603.SS) | 878 | 231% |

| China High Tech (600730.SS) | 494 | 150% |

| China West Medicine (600842.SS) | 593 | 270% |

| China Kejian (0035.SZ) | 820 | also received counter guarantees |

| China Tech Venture (0058.SS) | 415 | 249% |

| Shanghai Ninth Department Store | 567 | 84% |

| Hero Corp (600844.SS) | 472 | 82% |

| Shenzen Petrochem (0013.SZ) | 1,673 | 307% |

| Tongji Tech (600846.SS) | 2,240 | 67% |

| Source: New Fortune, December 2001, UBS Warburg | ||

Even when loans do get repaid, a study from Southwest Securities shows that more than three-fourths of parent debts are settled in-kind, with the equipment and property given being of subjective value. Only 17 percent of the debts in this study were settled with cash (Zhang, 2002b).

In addition, ongoing transactions between parents and listed SOEs are a significant problem. New Fortune reported in December 2000 that 93.2 percent of A-Share companies have disclosed ongoing significant connected-party transactions with their parents (Zhang, 2002b).

Owing to these relationships and corporate structures, Zhang argues that many listed companies could never become fully independent of their parents. He cites examples of Kelon, which went public without any of the three brands of their refrigerators and air-conditioners. The brands, Kelon, Rongsheng, and Huabao, are controlled by the unlisted parent. In the case of Yanzhou Coal, the mines went public without railway links to the public railway system.

Why Listing Did Not Significantly Improve Corporate Governance

While the Wang data set is robust given the firms that have listed to date, it is not necessarily a good representation of the average SOE that will be listed in the future. Historically, the Chinese quota system for determining listed SOEs was politically driven and administered geographically. First, the quota system for listing SOEs did not prevent poorly performing SOEs from being listed. Indeed, local governments often "bundled" poorly performing SOEs with better-performing SOEs before taking them to the market in the practice of "packaging" discussed earlier.

Second, abuse of listed firms is probably commonplace. If each province only receives one opportunity to access the public markets through a listed firm, the umbrella of political influence becomes even more imposing. Use of funds is not going toward productive investments in the listed firm but instead serves as payback to the community. Contrary to the goals of improving independence and corporate governance, listed SOEs that come through a political quota system can be strapped with obligations to the community, actually becoming less independent and less financially viable.

At a more fundamental level, SOE listing did not significantly improve corporate governance because the state did not—and still does not—want to give up its control of SOEs and embrace full privatization. As discussed earlier, the state merely views listing as a pragmatic way for cash-strapped SOEs to raise funds without full privatization. As long as the state maintains substantial ownership interest in SOEs, it will keep bailing these firms out of financial crises one way or the other ("soft budget constraint" la Kornai). As a result, the disciplinary role of the financial market will be severely undermined, and SOEs will not really be penalized for poor corporate governance.

Finally, in a thin capital market with few investment opportunities, vast amounts of household savings seeking investment opportunities made—and still make—it easy for any listed firm to raise equity even without sound corporate governance (Lin, 2000).

Looking ahead, more opportunities to raise the quality of listed firms will be available as the market—not politicians—determines which firms most deserve to be listed. In addition, the CSRC has implemented an innovative way to improve quality by putting more screening responsibility on investment banks through its own form of quotas. In our interviews, we learned that each investment bank is only permitted to have five filings under review by the CSRC at any given time. This provides a strong incentive that only the best companies, with the best chance of clearing approvals, will be submitted after more extensive due diligence.

The CSRC has cracked down on poor performers and has been trying to remove the implicit government guarantee of solvency through delisting. Laura Cha says a primary intent of this crackdown is aimed at reforming packaged companies. "The first purpose is to avoid packaging-oriented reorganization. Pocketing money through reorganization is intolerable, and we will watch more closely the reorganization of listed companies. Second, if over 70 percent of the reorganized company is new business, it should be regarded as a new company that will go through procedures as a newly listed company and receive the examination of the Public Offering and Listing Review Committee under the CSRC. Only when it lives up to the conditions of a listed company can it continue to maintain the status of a listed company after the reorganization" (Hu et al., 2002).

Wang's empirical evidence should serve as a wake-up call for investors and listing SOEs, but it is not an outright indictment against listing SOEs as a means to improve corporate governance. Studies of privatization in other emerging markets generally agree about the productivity and performance benefits of reduced state ownership. Additional studies of listing and corporatization as a step toward privatization in other former socialist economies may provide further support for a more optimistic view.

Next Step after Listing: Dilution of State Ownership

In addition to reducing state ownership of SOEs, listing of SOEs is also a way of monetizing firm values to support pension and social safetynet obligations. However, initial equity offerings only amount to a small fraction of state ownership, and the state continues to control most listed SOEs. The next big challenge is how to sell additional shares and dilute the state to a minority shareholder to improve governance. The value of private ownership and independence of former SOEs is well documented in separate privatization studies by Megginson, Frydman, and Pohl (Nakagane, 2000). However, the mechanism in China is different from other successful privatization efforts.

In 1997, in President Jiang Zeming's speech at the National People's Congress, he announced a policy called "releasing the small and retaining the large enterprises" (zhuada fangxiao). This marked the start of a process of significantly diluting state ownership in small- and medium-sized SOEs, especially through listing. As a matter of policy, the state will continue to retain controlling ownership of the very large SOEs out of strategic considerations, even if these companies are taken public.

According to Elaine Wu, an analyst with China Southern Securities, "the state-share sell-down is the most sensitive topic in the markets. Whenever there is some news on it, investors immediately become nervous and sell stocks" (China Online, 2002).

The key conflict in state-share sales is between market prices for existing minority shareholders and for the beneficiaries of stock sales, namely social security funds. Without sufficient liquidity in the market, or investor appetite for the quantity of shares available for sale, stock prices would collapse with state shares flooding the market. Clear market reaction has been seen on this issue. In June of 2001, the announcement by the CSRC that the state would sell shares equal to 10 percent of public offerings was met with a 30 percent decline in the Shanghai index, which lost RMB600 billion (US$72.5 billion) in value over four months. The state social security fund was an investor in Sinopec and lost RMB160 million (US$19.3 million) in value over the same period. In early 2002, when confirmed rumors emerged that the CSRC would shelve any plans for the sale of shares, the market responded with a 10 percent rise.

As discussed in the previous section, China needs greater stability among its investors to absorb the quantity of shares that need to be sold by the state. With a market presently made up of many gambling retirees, it is not surprising that the market reacted so strongly to the issue of state share sales. Obviously, lack of liquidity and the speculative nature of China's market are other important issues at work, but the sale of state shares is an extremely sensitive topic.

There is also a lack of coordination among interested government parties on whether and how to continue to sell state shares. After halting the June 2001 plan in October, Zhu Ronji was already urging the CSRC to develop new measures to continue state share sales by December. At a conference in Beijing, Zhu said that China would not discontinue the sell-off of state shares because it is needed as a source of cash for the social-security fund (China Online, 2001).

It seems that everyone involved in the market has an opinion about how state shares should be sold off. In 2001, the CSRC solicited opinions on its website and received 4,137 suggestions (Hu et al., 2002). Recent comments from the CSRC on the subject outlined the CSRC's commitment to the following principles: state-share sales should create a favorable situation for all parties involved; they should be conducive to the long-term development and stability of the stock markets; they should realize full tradability of the stocks of newly listed companies; and the interests of all parties should be protected and investors' losses should be reasonably measured and compensated (China Online, 2002).

It is clear that any solution will take a modest approach, and most agree that the timeframe for execution will span one to three years. Some alternatives being considered include allowing investors to bid for state shares through open, competitive tenders, beginning with SOEs that were listed earliest. Compensating investors for losses caused by the flood of shares on the market might include the issuance of bonus shares or stock options. Lockup periods to prevent flipping were also suggested, as was the ability for companies to buy back their shares if their stock prices become too low (China Online, 2002).

In agreement with statements from Zhu Ronji, Anthony Neoh[7] thinks the central government's primary motivation for selling state shares is to raise cash to fund social obligations and government budgets. In that case, creating confidence and stability in the stock market is a driving force in the decision of exactly how to dispose of state shares and dilute ownership in SOEs. Failed experiments began in 1999, with the attempt to sell a portion of state-owned shares in 10 firms of various sizes and industries. The original plan was complicated and tentative, providing an unclear timeline and unclear quantities and trading restrictions for institutional investors.[8]

Neoh believes that a proposal to create a closed-end mutual fund of state shares in SOEs will deliver a number of benefits for investors and for the state. Creating a diversified index allows the state to monetize a large amount of shares in a wide variety of firms. Investors have the opportunity to limit their risk by investing in the broader market instead of investing in individual firms.

Other proposals include allocating shares directly to the social security fund, which then has the ability to sell shares as cash is needed to fund obligations. Chen Zhiwu, professor of finance at the Yale University School of Management, proposed this solution (China Online, 2001).

The Most Viable Proposals for State-Share Sales

The problem of selling state shares cannot be considered without considering the missing link: sufficient demand. Institutional investors, especially those with foreign money or western investment philosophies, are key to generating a stable market environment for state shares. Assuming this issue will be solved through the WTO and continued regulatory reforms, two of the proposals mentioned above seem to balance the needs of the state and the needs of investors.

First, the index fund plan sounds very credible and has the added benefit of offering a viable investment vehicle for institutional investors with low entry costs. It is not clear that this proposal will go far to improve governance, however. The problem of small shareholders having little influence and representation with management would persist in a closed-end fund arrangement. Significant shareholders in the fund may not be very significant holders at the enterprise level and thus have little power over management. The other question is about the long-term fate of the fund and the individual SOE shares. How long will shares be locked up in the fund, and will the fund eventually be dissolved with distributions to shareholders? Finally, will the closedend fund be the best way to maximize value for state shareholders if net asset values of the fund are based on illiquid share prices of SOEs traded outside the fund?

Second, distribution of shares to social security funds is also a promising approach. After SOE shares are monetized, the funds should be permitted to reinvest in the broader market. The benefit is that cash reserved for long-term obligations can be plowed back into highquality corporate bonds and certain equities to provide a significant institutional presence in the market. Implementation will be key with this proposal. If one or several funds are established and are given flexibility about when to sell shares, the approach may be no better than the CSRC's initial attempts at state-share sales.

Implementation Limits: Connection to Bank Reform

The institutional support structure required for strong governance and independence of SOEs cannot be ignored. Strong, independent institutions support the development of market mechanisms, and they impact managers' ability to finance and run a publicly listed SOE. If financial institutions continue to be controlled by the state, the layer of political influence is not far removed from a listed SOE. Foreign sources of financing without political baggage are only available to a small number of high-profile SOEs. Weiying Zhang recommends that both financial and nonfinancial state enterprises be privatized concurrently (Nakagane, 2000).

Since the equity market is so interconnected with the overall capital market, this discussion of SOE listing would not be complete without addressing reform in the debt and banking sectors. As competition for capital increases with SOE listings, so should competition increase in banking. The capital markets should serve as a source of oversight and incentives for SOEs to operate more competitively. In the next section, we will address banking reform and its connection to corporate governance.

Banking Reform and Corporate Governance

Much of the reform in the banking industry in China since 1978 has been driven by the need to recapitalize the SOEs. Past lending practices that were entirely based on political considerations, coupled with poor performance of the SOEs, have left Chinese banks with a large amount of bad loans. Against the backdrop of China's entry into the WTO and further penetration of the foreign banks, the state-owned banks and private banks are all struggling for independence and profitability.

In recent years, China has seen some dramatic growth in the real sector, and private enterprises contributed 30 percent of total GDP in 1999. However, only 1 percent of private enterprises' financing comes from bank lending and only 1 percent of listed companies on Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges are private enterprises (Langlois, 2001).

Furthermore, given the disciplinary effect of banks' profitability and good corporate governance in the companies to which they lend, the banks should be a contributor to China's economic growth and not become an impediment to the growth.

It is therefore important to look at both drivers of the banking industry going forward: the legacy problems of the nonperforming loans (NPLs) and the future reforms of banking. Two key questions are:

-

How successfully will the Chinese banks deal with NPLs? NPLs have been the result of poor corporate governance both in the SOE debtors and within the banks themselves. The following discussion analyzes the recent efforts by the government to reduce NPLs.

-

How fast can the Chinese government further deregulate the banking industry? It is clear that further reform measures will be needed to ensure: a) healthy development of the private banking sector; b) true competition among the "big four" state-owned commercial banks and c) efficient allocation of capital in the economy. (See box 6.3.5.)

Significant regulatory reform steps taken to reduce NPLs include:

-

Abolition of the mandatory loan quota system. (As a result, state banks could lend according to commercial considerations.)

-

Reclassifying bank loans into five categories in line with international practice (pass, special mention, substandard, doubtful and loss) in late 1998 to improve loan quality

-

Establishment of four asset management companies (AMCs) in early 1999 to absorb the four state commercial banks' NPLs with AMC bonds swapped at full value

-

Disclosing loan-defaulting companies in the interbank computer network and banning new lending to them

-

Setting up a national credit bureau for banks' reference when extending loans. By FY99, the database already covered over 1million borrowers in 301 cities

How Successful Will the Efforts to Reduce NPLs Be?

Since 1995, many of the banking reform measures have focused on solving the NPL issue. Several steps that have been taken are described in the sidebar above. However, at the end of 2000, even after transferring RMB 1.3 trillion of NPLs, the remaining NPLs still remained at 29 percent of total loans.[9] By any international standard, all of the Big Four banks are bankrupt. (See table 6.3.4.) Some have argued that as bad as the NPLs are, they are not an issue as long as the growth of new NPLs is curbed and the economy can slowly absorb the existing portfolio of bad loans. Others have argued that if the reforms are not successful, nonperforming loans will continue to grow and, ultimately, be the downfall of the Chinese economy.

| RMB (billions) | Outstanding NPLs transfer to loans | AMS | Remaining NPLs | NPLs as % of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | ||||

| Industrial and Commercial Bank of China | $2,414 | $410 | $796 | 42.7% |

| Agricultural Bank of China | 1,484 | 346 | 490 | 45.7% |

| Bank of China | 1,378 | 296 | 394 | 41.2% |

| China Construction Bank | 1,386 | 280 | 394 | 40.4% |

| Total | $6,662 | $1,332 | $2,074 | 45.5% |

| Source: UBS Warburg estimates Note: For ICBC, ABC, and CCB, remaining NPLs assumed to be 33% of outstanding loans in 2000 | ||||

Corporate governance is at the heart of solving the NPL issue. The four asset management companies (AMCs) set up to help reduce the NPLs will likely not solve the problem, because the corporate governance of the AMCs is not properly structured. The AMCs are in fact set up as another type of state-owned enterprise under the regulatory oversight of the People's Bank of China with input from the Ministry of Finance. Currently, their major activity is debt-equity swaps (i.e., AMCs acquire NPLs from the banks and then convert those assets at par into direct equity holdings in the defaulting borrower, namely large SOEs). However, the SOEs chosen for this swap are selected by the State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) and not the AMCs themselves. The AMCs also have no power to change the management of the banks or to perform any kind of restructuring of the banks. They also do not take any control of the board. Without power as shareholders and without political independence, the hope for successful loan recovery lies in the specific methods AMCs will apply. However, evidence shows that after the debt-equity conversion of the assets are transferred to AMCs, the governance structure of the banks remains unchanged, and thus the physical restructuring of the enterprises remains unchanged. After almost two years in operation, AMCs had only disposed RMB $90 billion in assets (7 percent of total transferred assets), and the recovery rates for the disposed portion did not even exceed 10 percent.

On the other hand, according to UBS Warburg, the growth of new NPLs in the last two years appears to be very low. The banks said that new NPLs should be below 5 percent of total loans, or even as low as 1–3 percent. According to the report, the improvement is mainly due to tightened credit risk control procedures. For example, the Bank of China has established credit evaluation committees within the bank to approve individual credit applications. If the banks can continue to slow the growth of new bad loans, then the existing NPL problem can be isolated and slowly absorbed by the banks. UBS Warburg suggested that for the past two years, however, the new low NPL figure is mainly due to more personal-mortgage lending and long-term infrastructure projects lending. According to China's accounting standard, these loans will not be considered nonperforming until maturity. Many experts also suspect that there is still a lot of policy lending masked by the commercial banks, which understates the ratio of NPLs to total loans. Because relationship-based lending continues to dominate, and commercial banks are taking on infrastructure lending, the NPL issue is not likely to be relieved soon. Therefore, it still remains to be seen whether the banks have really become more efficient at capital lending. (See box 6.3.6.)

"China's big four banks need at least 10 years to deal with their problem loans and the cost of the necessary write-offs could equal US$518 billion," according to S&P. "Consequently, they are unlikely to meet the target set by the central bank—to cut their nonperforming loans to 15% of total loans within 5 years," said S&P director of financial services Terry Chan at a press briefing in Hong Kong on May 9, 2002. S&P's assessment of China's banks comes a day after economists at the Asian Development Bank's annual meeting in Shanghai called for urgent action on the bad loans problem.

Chinese central banker Dai Xianglong said that the NPLs of the Big Four could stand at 30 percent of their total loans, revising earlier, lower estimates. But S&P said on May 9, 2002, that the real figure is likely to be even higher.

The write-offs required are almost half of China's estimated gross domestic product of RMB1.1 trillion last year, or US$518 billion, said S&P. "The rate of NPL reduction desired by the authorities will almost certainly need some form of government intervention, possibly through injections of fresh capital and through further transfers of NPLs to asset management companies owned by the Ministry of Finance," S&P said.

Fresh equity could also take the form of a public listing of the banks, and S&P says it is more likely that the Big Four will tap the domestic market. "Thirty percent NPLs is too high a risk for the appetites of international investors. Technically, these banks are insolvent," said Mr. Chan.

The banks will have to balance the write-offs and provisioning against scaring potential investors off, so the rate of write-offs will be slow, said Mr. Chan. But he said that compared with Japan, China has bitten the bullet and is taking steps to reform the banking sector. "They need to do more, but at least they have acknowledged they have a problem."

—The Business Times, May 10, 2002

Continued corporate governance reform is also the key to curbing future NPLs because it will directly influence banks' risk management, asset allocation (loan portfolios), and strategy. Since 1998, most of the banks are holding branch managers responsible for poor performance and rising bad debts.

While government control gives rise to corporate governance problems across all corporations, it tends to be worse for banks. Banks are particularly opaque, and it is very difficult for outsiders to monitor and evaluate bank managers (Caprio and Levine, 2002). The tacit protection by the government further exacerbates the agency problem at the banks. Under the current Chinese banking system, in which the banks are still not allowed to compete effectively because the interest rates are not liberalized, the monopolistic nature further contributes to the opaqueness of the banks.

What is good corporate governance of the banks? Minsheng Bank has been publicized as a prime example of good corporate governance in China. Corporate governance, according to the OECD notion, is a set of relationships between the management and the board of directors, shareholders, and other interested parties. Separation of the functions with clearly defined accountability, responsibilities, and checks-and-balances among them is usually considered good corporate governance. Specifically for a bank, however, corporate governance will directly influence the bank's risk management, asset allocation (loan portfolios), and strategy.

Without the history of poor lending practices and unburdened by as many NPLs, the shareholding banks and the private banks are much more nimble and have been leaders in corporate governance. At the October 2001 Asia Pacific Summit held in Vancouver, Mr. Liu Ming Kang, chairman and president of Bank of China, specifically pointed to the following five aspects of corporate governance:

-

Formulating development strategy

-

Improving the decision-making process and internal control

-

Adopting prudent accounting norms and increasing transparency

-

Establishing a rigorous responsibility and accountability system

-

Strengthening human resources management and building a distinctive corporate culture

For example, at the Bank of China, Liu has set up checks and balances so that no official, himself included, can make policy loans. Due diligence and risk management committees in the head office and branches now assess all loans. Liu has no seat on those committees. "If the committee says no, I could not say yes," says Liu. Conversely, if the committee approves a loan, he can veto it. At the same time, Liu is trying to ensure that each loan application gets approved or rejected within 10 working days, compared with the several months it sometimes took before Liu took over in 2000 (Mellor, 2002).

However, even given the amount of publicity on banks' corporate governance reforms, many experts believe that both central and local governments still have strong influences on lending practices at various bank branches. Although lending quotas have been abolished, new lending practices based on relationships with the SOEs are essentially the old practices under a different name. The government has also, at times, returned to old habits. For example, as economic growth slowed in 1998–99, the central government asked the commercial banks to contribute by taking up infrastructure loans to boost GDP (HSBC, 2001). An issue to watch, therefore, is whether the "healthy" banks in the industry have become independent enough to resist this kind of pressure in the future.

China's entry into the WTO will allow Chinese banks to seek foreign capital—through joint ventures, for example—and also penetration of foreign banks into the Chinese market. Will these changes drive the banking industry to greater health? Corporate governance and operational reforms can only function well when there is a foundation from which the firms can compete effectively. After much reform, the current Chinese banking industry still remains a heavily regulated market with the Big Four banks controlling approximately 70 percent of the total assets. Therefore, this naturally leads to the next key question: How fast can the government further deregulate? We will lay out some of the objectives for the government for the next few years.

How Fast Can the Chinese Government Further Deregulate?

A well-run financial market allows financial intermediaries to efficiently allocate capital across the economy. Under the existing structure, however, both the Big Four banks and the shareholding banks access the same resources, compete for the same clients with the same set of products, and essentially have the same shareholder. What further reforms are needed to bring true competition? There are five major areas in which the government should further deregulate:

-

Regulatory rigidity: Currently, the establishment of all financial services firms has to be preapproved by the central government. Firms with primary private sponsors are either not approved or approved with crippling business restrictions. Therefore, competition is only among the banks that are still government owned and controlled. Two other examples include: a) the requirement for banks to receive approvals for every line of business, and b) slow deregulations in allowing new sources of capital.

-

Unliberalized interest rates: The interest rates on loans and deposits offered by financial institutions are set centrally by the People's Bank of China (PBOC). Financial institutions have some leeway in setting lending rates: they can vary the centrally governed rates by 10 percent for lending to large institutions, and up to 30 percent for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). If banks are not allowed to price lending rates themselves, they will not be able to compete on the basis of interest rates. The three-year liberalization timetable announced by the PBOC governor in 2000 has basically been dropped. The reason given is that after the recent liberalization of foreign currency interest rates, there was a sharp jump in foreign-exchange deposit rates but little change in the foreign-exchange lending rate. This has resulted in a reduced interest spread. Currently, a high RMB interest spread is a major factor in domestic banks maintaining their financial strength. Therefore, the PBOC is worried that the push on interest rate liberalization will cause the interest spread of the RMB business to fall as well.

-

Denial of market allocation of capital: To date, the corporate bond market has been suppressed because the law requires that all corporate bonds be sold as public instruments and because the state imposes minimum requirements to issue: minimum net assets, maximum debt/assets ratio (40 percent), and one-year debt service capability. The result is that almost 100 percent of corporate risk in China is on bank balance sheets and is mispriced (Langlois, 2002).

-

Excessive taxation: Even though the banks make no money on lending, they still pay heavy taxes: 7–8 percent business tax, 33 percent income tax with extreme restrictions on provisions for nonperforming loans (<1 percent of loans) and restrictions on expenses (compensation) (Langlois, 2002). In 2001, however, the PBOC did announce a policy to cut banks' business tax from 8 percent of total operating income (after deducting interest income from financial institutions and government bonds) to 5 percent by 2003. In order to make the Chinese banks truly competitive, we believe the business tax must eventually be scrapped. The corresponding tax loss to the government, estimated at around 2 percent of government revenue, should be bearable given the rising tax contribution from other sectors (HSBC, 2001).

-

Continuing to open China to foreign banks: Only in February 2002 did the government grant new licenses to provide foreign currency services in China for local customers. However, according to PBOC, as of the end of June 2001, foreign banks in mainland China had total assets of $41 billion, representing only 2 percent of total assets. Although foreign banks will have very limited distribution networks, their services are more competitive than Chinese banks. The rules published in February 2002 were considered by some to be a milestone in China's meeting the concessions necessary for entry into the WTO. Nonetheless, some foreign banks still felt that the rules fell short of the expectations because of the stringent capital requirements for foreign banks planning to enter China (Peoples Daily, 2002).

In the meantime, however, the banks are trying to become more competitive by becoming corporatized—more shareholding banks as well as the Bank of China are trying to get a public listing on China's stock exchange.[10] It is believed that going public can help support the capital expansion needed by the banks. Mergers, reorganizations, and business combinations will also improve banks' economies of scale, thereby increasing banks' capabilities for resisting risk and enhancing their competitiveness as a whole. However, will corporatization work? Listing banks is a step in the right direction, but without the necessary foundation (discussed above) and given the still underdeveloped securities market, the impact of listing on banks' profitability is still unclear.

Conclusion

We attempted to address some of the most important issues in corporate governance and financial market reform in China. The significant hurdles that China must overcome encompass four areas: the legacy of a quota-based listing process; the role of the CSRC (China's SEC); the development of a liquid market with institutional investors; and the opportunity to bypass the domestic market and finance companies abroad.

Corporate governance in state-owned enterprises has the potential to be addressed through the process of listing SOEs and diluting state ownership. The results that remain to be seen are whether:

-

listing of SOEs really improves corporate governance

-

the initial public offering of SOEs is sufficient, or if the state should quickly dilute its ownership in order for better governance to take root

-

better financial performance will eventually follow from listing.

We also examined the connection between nonperforming loans, banking sector reform, and corporate governance. Two factors are critical to success here: how successfully the Chinese banks deal with nonperforming loans, and how fast the Chinese government will further deregulate the banking industry.

To compete effectively on a global scale and successfully transition to a market economy, China must have well-functioning securities markets and banks to establish the foundation for strong corporate governance.

Methods and Acknowledgments

The student research team would like to thank Professor Stewart Myers for his guidance and contributions to this work as our project advisor. Our research was conducted through a combination of primary and secondary research, including interviews on location in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Beijing in early 2002. We would like to thank each of the following people for their contributions to our understanding of the background and challenges of financial reform and corporate governance in China: Laurence Franklin and T. J. Wong, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; Leslie Young, Chinese University, Hong Kong; Earl Yen, Ascend Ventures, Hong Kong; Marjorie Yang, Esquel Group, Hong Kong; Laura Cha and Anthony Neoh, CSRC, Beijing; Lawrence Li, Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission; Jaime Allen, Asian Corporate Governance Association, Hong Kong; Victor Fung, Chang Ka Mun, and Chin Wai Man, Li & Fung, Hong Kong; Joe Zhang, UBS Warburg, Hong Kong; Dr. Yuan Cheng and Zili Shao, Linklaters, Hong Kong; Fang Xinghai, Shanghai Stock Exchange; Lu Wei, Fudan University, Shanghai; Yibing Wu, McKinsey & Co., Beijing; Wang Yi, China Development Bank, Beijing; Jin Shuping and Wei Shenghong, Minsheng Bank, Beijing; Chen Taotao, Tsinghua University, Beijing; Colin Xu, World Bank, Washington, D.C.; Stoyan Tenev, Shidan Derakhshani, Jun Zhang, and Mike Lubrano, International Finance Corporation, Washington DC; Mengfei Wu, CNOOC, Hong Kong; Edward Steinfeld, MIT, Cambridge; Dean Alan White, MIT Sloan, Cambridge. Of course, many comments were made in confidence, so we are unable to attribute every statement from these sources. Special thanks are extended to Laurence Franklin, Marjorie Yang, and Laura Cha, whose insights and referrals to other sources of information in Hong Kong and Beijing were most appreciated. Dean Allen White of MIT Sloan was also extremely helpful in establishing contacts for our team in China.

References

Caijing Magazine, January 23 through China Online.

Caprio, Gerard, Jr., and Ross Levine. 2002. "Corporate Governance of Banks: Concepts and International Observations," April 25, 2002.

China Online. 1999. Ten Chinese Firms Chosen to Sell Government Equity. November 30.

China Online. 2001. Zhu Rongji says sell-off of state shares must resume. December 19.

China Online. 2002. Worries over state-share sales trigger stock slump. January 28.

Cull, Robert, and Lixin Colin Xu. 2000. Bureaucrats, State Banks and the Efficiency of Credit Allocation: The Experience of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises. Journal of Comparative Economics 28: 1–31.

HSBC Securities (Asia) Limited, Banks / Financial Research. 2002. "Form Command to Demand in Financial Services—Entering the China Century," February 2001.

Hu Shuli, WeiFuhua, and Niu Wenxin. 2002. An interview with Laura Cha, CSRC vice chair.

Langlois, John D., Jr. 2001. "China's Financial System and the Private Sector," presentation at American Enterprisse Institute, May 3, 2001.

Lardy, Nicholas. 1998. China's Unfinished Economic Revolution (Brookings).

Lin, Cyril. 2000. Public Vices in Public Places: Challenges in Corporate Governance Development in China. OECD Development Centre. Draft.

Mellor, Williams. 2002. "Cleaning Up Bank of China." Bloomberg Markets, April.

Nakagane, Katsuji. 2000. SOE Reform and Privatization in China: A Note on Several Theoretical and Empirical Issues. University of Tokyo.

Neoh, Anthony. 2000. China's domestic capital markets in the new millennium, Chinaonline.com

Neoh, Anthony. 2002. Corporate Governance in China. Talk at China Harvard Review conference, April 13.

People's Daily. 2002. "Detailed Bank Rules on Foreign Banks Take Effect," February 2, 2002.

Shleifer, Andre, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. "A Survey of Corporate Governance," Journal of Finance 52, no. 2: 737–783.

Wang, Xiaozu, Lixin Colin Xu, and Tian Zhu. 2001. Is Public Listing a Way Out for State-Owned Enterprises? The Case of China.

Zhang, Chunlin, and Stoyan Tenev. 2002a. Corporate Governance and Enterprise Reform in China: Building the Institutions of Modern Markets. The World Bank. April.