Project Management at the Crossroads

Project management is now in the midst of a paradigm shift. The prevailing paradigm is starting to crumble. Discussions are already arising at forums and conferences that challenge the very foundation and prevailing knowledge base of professional bodies in the discipline. Presentations and papers are increasingly charging that the prevailing paradigm is mechanistic, eclectic, analytical, descriptive, and deficient . In the Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference 2002 , Lauri Koskela and Greg Howell stress that the shortcomings in the foundation of project management are becoming more and more apparent, creating a crisis that is gaining recognition. [8] Bruno Urli and Didier Urli also agree and compare project management to a toolbox of different instruments rather than a body of knowledge in the traditional sense. [9]

Yet, change is not easily forthcoming. Koskela and Howell further observe that the culprit behind the crisis is a lack of a theoretical foundation in project management. This circumstance has led to overlooking anomalies or misinterpreting their meaning and significance. [10]

To a large degree, the prevailing paradigm is dominated by its mathematical and scientific past. Urli and Urli note that what I refer to as the "mechanics" of project management have received the focus of attention. The areas have a strong management science and operations research flavor, represented by the topics covered, e.g., resource leveling and Gantt charts . [11]

In addition to finding its basis in tradition, the prevailing paradigm finds itself protected by an army of adherents to preserve its mathematical and rational roots. Pernille Eskerod and Katarina Ostergren note that the desire to treat project management as a scientific discipline and create a supporting theoretical basis has led to inflexibility. The reason is the desire to build the "right theory" based on standardization. [12]

I believe the application of project management as we know it today can worsen, not enhance, project performance by establishing a bureaucratic infrastructure that impedes rather than enhances project performance. Alberto Melgrati and Mario Damiani observe that the overemphasis of rationality on a project necessitates a more balanced perspective that considers other areas, including political and cultural considerations. [13]

Even the very purpose of a project has come under question. Connie Delisle and Janice Thomas observe that the traditional emphasis on efficiency, e.g., on time and within budget, is devoid of real meaning in terms of what success is to stakeholders as well as to a project. [14]

Peter Morris agrees, noting that being on time and within budget does not guarantee that the result will be something that meets needs or expectations. [15]

Eskerod and Ostergren agree that the current crack in the existing paradigm has shed a new light on the purpose of a project, indicating that it goes beyond time, cost, and performance. [16]

All of the above insights have far-reaching implications on managing and, more importantly, leading projects. Project performance has not improved dramatically over the years despite the proliferation of tools, techniques, and expertise. As observed earlier, the larger the project, the chances of project success decrease despite the implementation of project management disciplines.

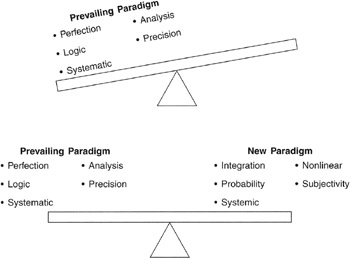

What is needed, I believe, is a change in the prevailing paradigm of project management, i.e., one that is a more balanced view that relies less on mathematical and rational orientations and more on what I refer to the " subjective " factors that play a major role in effective leadership, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Correcting the Imbalance.

Just about all the major factors that contribute to project failure and success link back not to more rationality and control, but to more communication and commitment, for example. Above all, projects are endeavors of human energy and ingenuity; not schedules, earned value analysis, and other tools and techniques.

Peter Morris observes that the major contributors to project failures relate to poor definition and control. [17] Such failures reflect more of a failure in leadership than the application of a tool or technique. With poor leadership, a sophisticated tool or technique only gives a bad leader the opportunity to do more damage. The person may be a better project manager, but he or she may not be a better project leader.

Project success, however defined, involves leading, not managing, people to accomplish goals. Christopher Bredillet agrees, noting that the emphasis on quantitative considerations constrains autonomy whereas qualitative ones provide the necessary freedom. [18]

The prevailing paradigm has led to a skewed perspective of what matters on a project. Kate Belzer says that knowing the "hard skills" of project management, e.g., tools, is an incomplete knowledge base. A good command of the "soft skills" is also necessary. This skill, which she refers to as the art of project management, helps to identify value, provide direction, and build teams to name a few. She also observes that a project has a larger chance of failure without the soft skills. [19]

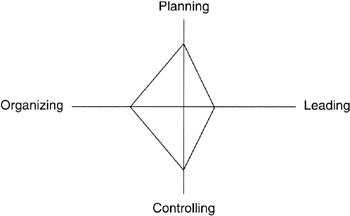

There is, unfortunately , very little insight on the importance of leading rather than managing projects despite its salient influence on project outcome, as indicated in Figure 3.2. Peter Morris says that this lack of insight is quite apparent when discussing teamwork on projects, whereby little discussion has occurred on its impact on project success. [20]

Figure 3.2: Spider Chart Reflecting Emphasis Under Prevailing Paradigm.

The bottom line is that the field of project management needs a more balanced paradigm. It leans too far to the left side of the brain; that is, it emphasizes too much the capabilities of the left hemisphere of the human mind. As Warren Bennis, a leadership guru, would say: Doing things right. What is needed more is to ask whether project managers are doing the right things, that is, applying the right side of their brain.

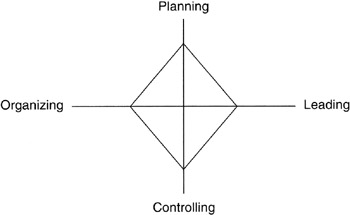

Perhaps Tom Peters summed up the entire problem with the prevailing paradigm of project management when he said, in an interview for PM Network , that too much emphasis has been placed on traditional project management, e.g., PERT. According to Peters, this overemphasis has its pro's and con's, providing a skewed perspective on project management. What is often overlooked is the emotional, people side of project management. Not surprisingly, the role of such factors as enthusiasm and creativity are often overlooked in contributing to success of projects, creating a serious gap. [21] Leading, as displayed in Figure 3.3, restores the balance.

Figure 3.3: Spider Chart Reflecting Emphasis Under New Paradigm.

[8] Lauri Koskela and Greg Howell, The underlying theory of project management is obsolete, in Proceedings of PMI Research Conference 2002 , Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA, p. 299.

[9] Bruno Urli and Didier Urli, Project management in North America, stability of the concepts, Project Management Journal , p. 33, September 2000.

[10] Lauri Koskela and Greg Howell, The underlying theory of project management is obsolete, in Proceedings of PMI Research Conference 2002 , Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA, p. 300.

[11] Bruno Urli and Didier Urli, Project management in North America, stability of the concepts, Project Management Journal , p. 37, September 2000.

[12] Pernille Eskerod and Katarina Ostergren, Why do companies standardize project work? Project Management , 6(1), 36, 2000.

[13] Alberto Melgrati and Mario Damiani, Rethinking the project management framework: new epistemology, new insights, in Proceedings of PMI Research Conference 2002 , Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA, p. 378.

[14] Connie L. Delisle and Janice L. Thomas, Success: getting traction in a turbulent business climate, in Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference 2002 , Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA, p. 193.

[15] Peter W.G. Morris, Why project management doesn't always make good business sense, Project Management , p. 12, January 1998.

[16] Pernille Eskerod and Katarina Ostergren, Why do companies standardize project work? Project Management , 6(1), 34, 2000.

[17] Peter W.G. Morris, Why project management doesn't always make good business sense, Project Management , p. 12, January 1998.

[18] Christopher Bredillet, Mapping the dynamics of project management field: project management in action, in Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference 2002 , Project Management Institute, Newtown Square, PA, p. 158.

[19] Kate Belzer, http://www.pmforum.org/library/papers/BusinessSuccess.htm

[20] Peter W.G. Morris, Why project management doesn't always make good business sense, Project Management , p. 14, January 1998.

[21] Jeannette Cabanis, Passion beats planning, limiting scope is stupid, women rule..., PM Network , pp. 30 “31, September 1998.

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 169