Section 8.1. Word Document Metadata

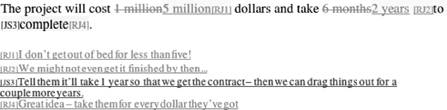

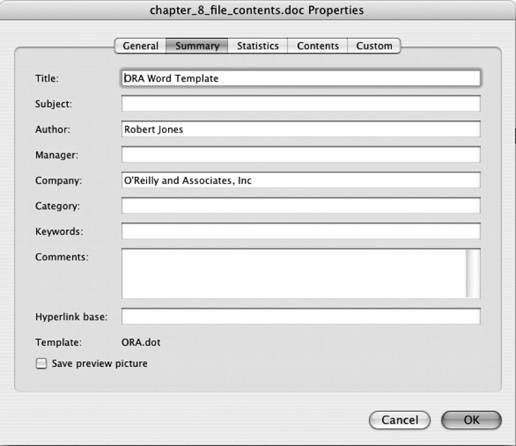

8.1. Word Document MetadataMicrosoft Word is probably the most widely used word-processing software in the world. Although the vast majority of people only use its basic functions, it has many advanced capabilities. One of the more well known of these is Track Changes , a set of reviewing tools that allow multiple people to modify and comment on a document. This is incredibly useful for writers and their editors, as well as for those involved in preparing legal documents or press releases, which require significant review and approval by multiple parties. When these tools are turned on, any text that is modified has a strikethrough line placed through it. The edits of different reviewers are recorded in different colors. Comments can be attached to any edit to justify the change or to convey information to the other reviewers. It is an invaluable feature that has been used extensively by my editor to keep me on the straight and narrow as I write this book. The downside of Track Changes is that a heavily edited document can be very difficult to read. The solution is for the primary editor or author to accept or reject the changes to the text using one of the tools. This clears out the strikethrough text and produces a clean document. But that can be tedious and a much easier way to clean things up is to hide all the edits by turning off Track Changes. The problem is that simply disabling the feature does not remove the changes from the document. Anyone who subsequently receives a copy can turn the feature back on and see all the previous edits and associated comments. This can be a very serious problem. Figure 8-1 shows a fictitious example of how Track Changes can display internal information that you might want to conceal from the final recipient of the document. Figure 8-1. An example of using Track Changes in Microsoft Word Often people modify existing documents rather than writing them from scratch. For example, I might use a business proposal for one client as the starting point for a different client's proposal, changing the names and parts of the content as appropriate. If Track Changes has been used and the edits have been hidden, but not removed, then the recipient of the new document may discover who else I have been working with, and perhaps how much I was charging them. These comments and edits are examples of metadata that augment the basic content of a document in various ways, and Microsoft Word documents can be packed with metadata. Open up the Properties window for a Word document, under the File menu. The Summary tab shows a series of text fields that can be filled in. The owner of the software is usually listed as the author, and perhaps the Company field is filled in. The rest of the fields are often blank. A whole range of other data can be entered under the Custom tab. These fields are used in companies that use a formal procedure for document approval. Any information entered into any of these fields is stored in the Word document as metadata. By default that information is visible to any recipient of the document. They just need to know where to look. Even if you never touch any of these fields, the Author field will carry the name of the owner of the software. Figure 8-2 shows the Summary window for this chapter of the book as I write it. Word has recorded my name, from when I first installed the software, and my apparent company, which it has pulled from the Word template file provided by O'Reilly. This information will be stored as metadata in the document and will be retained whenever the document is transferred and copied. This may not seem like a big deal but as we shall see, simply recording the author can cause a lot of problems. Figure 8-2. Document Properties window in Microsoft Word Often metadata results in the inadvertent disclosure of information. Most are merely embarrassing for the authors but some can have significant consequences. 8.1.1. SCO Lawsuit DocumentsOne notable example was a Word document that contained a lawsuit by the SCO Group against the car company DaimlerChrysler, accusing it of infringing SCO's patents. SCO contends that the Linux operating system contains some proprietary source code and intellectual property belonging to SCO. Their lawyers have been filing suits against a number of large companies that use Linux. A copy of the suit against DaimlerChrysler was passed to reporters at CNET, an online technology news service, in March 2004 (http://news.com.com/2102-7344_3-5170073.html). Seeing that the document was in Word format, they turned on the Track Changes feature and scored a journalistic coup. It turns out that the document originally referred to Bank of America as the defendant, not DaimlerChrysler. The references to the bank were quite specific, including one comment asking, "Did BA receive one of the SCO letters sent to Fortune 1500?," referring to an earlier mailing of letters to large corporations informing them about SCO's claims. They could tell that at 11:10 a.m. on February 18, 2004, the text "Bank of America, a National Banking Association" was replaced with "DaimlerChrysler Corp." as the defendant in the lawsuit. Comments relating to Bank of America were deleted and the state in which the suit would be heard was changed from California to Michigan. Other text that was deleted from the lawsuit before it was actually filed included specific mention of Linus Torvalds as being involved in the copying of their intellectual property and detailed some of the specific relief that SCO sought in the case.

Inadvertent disclosures such as these are remarkable. Not only do they serve as a very public embarrassment for the people who prepared the document, but they also reveal important details about their legal strategy. You can be sure that the lawyers at Bank of America were extremely interested in these revelations. 8.1.2. Other ExamplesThere are many examples of people being tripped up by Word metadata. Alcatel, a maker of communications and networking equipment, fell victim in 2001 when they issued a press release regarding their DSL modem. At face value, the release deflected criticisms of their modem by a computer security organization, remarking that all DSL modems were subject to the vulnerability in question. Enabling Track Changes in the Word document that contained the release revealed an entire discussion between Alcatel staff regarding the best way to handle the security issue. Comments such as "What are you doing to provide a legitimate fix?" and "Why don't we switch on firewalls by default for all of our customers?" did not inspire confidence in the company's response to its customers. In his New Year's speech in January 2004, Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen made bold statements about Denmark becoming one of the world's more technologically advanced countries. Unfortunately for him, the Word document containing the speech identified the original author as Christopher Arzrouni, a senior member of the Association of Danish Industries and a well-known proponent of relatively extreme political views. This revelation did nothing to help Rasmussen's attempt to distance himself from such views. In March 2004, the attorney general of California, Bill Lockyer, circulated a draft letter to his fellow state attorneys general in which he described peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing software as a "dangerous product" and argued that such software should include a warning to users about the legal and personal risks they might face as a result of using it. Failure to include such a warning would constitute a deceptive trade practice. The tone of the letter was extremely strong. The draft was distributed as a Word document, which showed the username of the original author to be stevensonv. It so happened that Vans Stevenson was the senior vice president for state legislative affairs of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) at the time. Given the MPAA's vigorous campaign against P2P software, this coincidence, and the failure of anyone involved to offer an alternate explanation, raised more than a few eyebrows in the P2P community. Even Microsoft is not immune to this problem. Michal Zalewski (http://lcamtuf.coredump.cx/strikeout/) has trawled through many publicly available documents on Microsoft web sites and uncovered numerous examples where comments and edits in marketing documents can be recovered by enabling Track Changes. |

- Step 1.1 Install OpenSSH to Replace the Remote Access Protocols with Encrypted Versions

- Step 3.2 Use PuTTY / plink as a Command Line Replacement for telnet / rlogin

- Step 3.4 Use PuTTYs Tools to Transfer Files from the Windows Command Line

- Step 4.1 Authentication with Public Keys

- Step 4.6 How to use PuTTY Passphrase Agents