Main Concepts

|

The Concept of Political System

Political system is widely understood to consist of all the forces, processes, and institutions of a society which generate effective demand and support inputs and the attendant political cooperation and conflicts and which are involved in the resolution of conflicts and subsequent evolution of authoritative political decisions (Kolb, 1978, p. 28). Citizens participate in governmental policy-making by voting, forming interest groups and making contact with politicians and civil servants. Different levels and functions of public institutions provide citizens with their own opportunities to voice their concerns and make sure that they will be heard in decision-making. Nevertheless, researchers have been unable to recognize definitive factors in government's institutions and processes which could increase citizens' probability to trust in it.

The political system of Finland is based on ideals of republicanism and constitutionalism. The former emphasizes political liberty that considers citizens' participation in sovereign deliberation necessary for the defense of democratic society (Viroli, 1999, p. 4). The latter describes purposes, objectives, and means of public institutions in bringing the governing and governed classes of the nation together, to secure the former in the possession of the power conferred on them, and the latter in the enjoyment of what freedom remains (von Humboldt, 1993, p. 135). Finland is basically a liberal democracy with Parliament at the center of government and local councils at the grass roots level and citizens are expected to use their political freedoms on both levels.

In addition to Parliament, there is the Prime Minister's Office and President at the central level. Government is politically responsible to Parliament in its decisions and action. Prime Minister chairs governmental meetings of the different number of ministers who lead ministries. At this moment there are 13 ministries and 17 ministers. This means that there are two ministers in some ministries each leading their own responsibilities. The number of ministers and ministries is always the object of political discussion after the national elections.

All matters to be decided by the Government are prepared in the relevant ministry. The ministries also handle a significant proportion of administrative issues belonging in principle to the Government as a whole. The area for which each ministry and minister is responsible by law is generally indicated by the name of the ministry. Matters which do not fall within the scope of any other ministry are handled by the Prime Minister's Office. The ministries together employ approximately 5,000 people.

At the regional level, there are both state and municipal authorities. Some ministries, but not all, have their own regional organizations that do not usually correspond with each other. Because of this, state regional organization is quite mosaic in its nature. Municipalities collaborate in vocational schools, and health and social services in regional levels. Ministries have also often their own organizations at the local level, where municipalities are the most important actors. They provide most public welfare services to citizens.

Central government (Parliament, the Prime Minister's Office and the ministries) operates in the framework of a market economy in which it purports to promote private property, entrepreneurship, a free price system, and competition with its powers to make laws and amend them. At the same time, government promotes a model of a welfare state, which has borrowed much from the experiences of Sweden, Germany, and the United Kingdom in providing health, education and social services for citizens. According to various surveys, citizens support the objectives and means of the welfare state or society despite their criticism of its deleterious outcomes like red tape, inflexibility, bureaucracy, and rising taxation (Kantola & Kautto, 2002, pp. 18–19).

In all levels of public administration, civil service has a long tradition of expertise, respect for rule of law, and division of labor between different sectors. Civil servants have always maintained the highly respected status among other professions in the society. Although local authorities enjoy constitutional guarantees for their autonomy as decentralized democratic institutions close to the citizens' heartbeat and concerns, many of them, especially small ones, are too dependent on the planning, financial, and problem-solving resources of ministries in their provision of basic social services.

In the last decade governmental bureaus in all levels have assumed and utilized quite extensively the philosophy of new public management in the purpose of developing public machinery as thoroughly as possible. It promotes the quality of its services, the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations, the professional leadership of its organizations, and the national capability to compete in domestic and global markets (Holkeri & Nurmi, 2002). Studies on ministries show that civil servants are confident about their ability to run them correctly and make them work for the public interest (see, for instance, Stenvall, 2000). International comparisons show Finland to be one of the least corrupt countries in the world due to the high ethical standards public authorities follow on central, regional, and local levels (see OECD, 2000, pp. 142–143).

Citizens and Political Opinions

Citizens have many roles in their society: They are producers, consumers, taxpayers, applicants, etc. In terms of intergovernmental relations and political participation, it is important to realize that the smaller the democratic unit is, the greater is its potential for citizens' active involvement and the less the need for citizens to delegate public decisions to representatives (Dahl, 1998, p. 110). This is an important observation, because it means that citizens at local level are in a better position than at central level to acquire personal experience and knowledge to sustain their trust in the way in which local authorities are managed and how issues are handled in them.

The case is different with governmental agencies at central level. It is time-consuming, costly and difficult for citizens to personally know about what is going on in these agencies and how things are processed in them. In spite of this, it must be supposed that they could have at least a certain level of trust in ministries' willingness, ability, and capability to act for the best interests of the country. We hypothesize that the way in which people experience policies in their lives will crucially determine to what extent they trust in ministries. We also argue that reading newspapers, listening to radio, and watching television will give them raw material to make their minds up about trusting or distrusting public organizations.

It may be that there is always a certain degree of subjectivity and randomness in citizens' trust in ministries with which they do not usually have direct experience. Although the nature of political opinions is fragile, they must not be dismissed out of hand. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, who denied that opinion provides access to truth, John Stuart Mill, in his book On Liberty, appreciated people's political opinions and thought that opinions can guide their behavior and choices in political and economic arenas (see Vaughan, 1998, p. 58). Mill did not claim that opinions conceal the truth sought by philosophers, but instead that each opinion contains a partial truth that is revealed only through discussion and debate about what going on (Vaughan, 1998, p. 58).

According to Vaughan, John Rawls concurs with Mill in the question of opinions: To Rawls, considered judgements are roughly like opinions which cannot be trampled underfoot even if they are not demonstrably true (Vaughan, 1998, p. 57). For Rawls these judgements arise from people's sense of justice, and therefore, they must be respected for their approximation to justice itself (Vaughan, 1998, p. 57). People's opinions may have political clout even if they are highly subjective and uncertain. They are the starting point for discussion and dialectic reasoning. From this point of view, it is acceptable and legitimate to investigate how citizens feel and assess the importance, functions and outcomes of political institutions.

In his analysis of representatives and constituents, William Bianco apparently accepts the same position on opinions as Mill and Rawls when he argues that assuming that people make rational, purposive choices says nothing about the quality and quantity of information available to them (Bianco, 1997, p. 43). For Bianco the tenets of rational choice apply equally to situations in which people have a complete, accurate understanding of the consequences of their decisions as they do to situations characterized by incomplete information where players are unsure or misinformed about the consequences of their actions. He uses the term belief interchangeably with judgements, assessments, inferences, and perceptions to describe what people think they know of policy implications. People assess policies even if their beliefs are held by others to be inaccurate or senseless (Bianco, 1997, p. 44).

It is also essential for political decision-makers to know about how they are perceived and evaluated by citizens so that they can critically reflect their fundamental motivations and possibly rearrange their priorities. It may not be rational for them to require citizens to know at least approximately the same facts, details, and argumentation that are assured them in order to be in a legitimate position to evaluate their choices. This is because citizens think of public policies in terms of their effects on their own choices, preferences, and objectives.

Leadership in Policy-Making

Policy-making can be defined as political decision-making in which government initiates, designs, implements and evaluates its policies. It refers to government activities in innovating, maintaining and changing policies. Government's policy-making always occurs more or less in interaction with a society from which politicians and civil servants receive information about problems and possibilities, demand and support (Ellsworth & Stahnke, 1976, pp. 86–87).

It may not be the ultimate objective of democratic governance that citizens must always be able to steer and control the use of governmental policy-making in service, regulation and financial transfers as closely as possible; the three principal areas of public activity. However, if this is assumed to be the prerequisite for democratic administration it could in time prove impractical, delay the process of policy-making and even bring it to a standstill. As a result, the real question of political leadership in policy-making is to make sure that citizens are willing to sacrifice for a policy judged by the political leadership to be indispensable to the nation's self-presentation (Ciepley, 1999, p. 207).

This interpretation of Ciepley is based on Max Weber's theoretical ideas on the role of political leadership of governmental institutions that shift the focus from the "demand" side to the "supply" side of the electoral and other democratic processes linking citizens and governmental apparatus together (Ciepley, 1999, pp. 192–193). This Weberian approach allows Ciepley to offer a rationale for democracy which is compatible with the public ignorance of the essential details of policy-making, citizens' fragile opinions of its impact on the nation, and constitutionalism which provide government with the legal right and sphere of action. According to Ciepley, if a democratic political system presents its electorate with a choice to the problem, the country is going to be well led, no matter how ignorant the general public is about the policy issues (Ciepley, 1999, p. 193). When policy alternatives have been given to citizens by government; it is up to citizens to choose to what extent they deem them beneficial or deleterious for themselves.

Political leadership in policy-making could be conceptualized as providing alternatives for citizens in services, regulation, and financial transfers. These are three principal functions of public authorities. As to elections, it means that citizens will decide in them only tentatively, but not authoritatively, what issues must be chosen for policy-making and how they should be resolved. In elections citizens authoritatively choose political parties and people whom they will hold responsible for policy-making. This does not, however, mean that representatives should not engage in dialogue with their voters in order to know what they think of alternatives and understand their preferences in issues. The concept of political leadership as a provider of alternatives also allows continuous development of intimate relationships between the policy-making community and citizens.

In this sense political leadership is supposed to be an active force within its constitutional boundaries. It is active both in policy-making and in engagement with voters, supporters and other people and groups that may have interests in a policy. Political leadership consists of democratically elected representatives and civil servants. Unlike citizens who assess policy choices from the perspective of their own present and future conditions, researchers may also want to know about who makes up the political leadership of a policy. They may also want to know who makes general policy questions, what motivates the decision-makers to make policy, what influences policy choices and what are the major types of decisions (Ellsworth & Stahnke, 1976, pp. 34–35).

Trust in the Policy-Making Capability of Ministries

There are many different definitions of trust which we have discussed in our first article in this book (see especially Harisalo & Stenvall, 2004). Based on what we have said above about the importance of people's political opinions and understanding of political life, we define trust in governmental agencies as people's political calculation based on more or less accurate beliefs, opinions, or considered judgements over policy implications of which ethical expectations, benefits, and impacts are the most relevant for them. Thus, trust calculation occurs in more or less the same focused way between people and between people and public policies (see Harisalo & Miettinen, 1997).

As argued above, people may pay more attention to how governmental policies affect them than to government's argumentation and political purposes. It could also be so that citizens maintain their trust in ministries in spite of negative effects of their policies on them. Citizens' trust in policy-making could take shape in social interaction from which government is excluded. The nature of their trust calculation could be either well or badly informed.

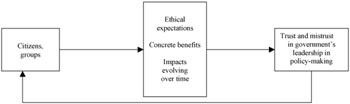

We argued above that ethical expectations, benefits, and impacts influence to what extent citizens and groups trust or mistrust government's leadership in policy-making. Ethical expectations are in the nature of moral or normative demands concerning government's actions in order to alleviate social problems, change conditions more or less radically in a society, and help people in different needs. These expectations create a more or less effective demand for government to act or stop acting.

Benefits are concrete advantages that policies have brought about for people and various groups. The more beneficial the policies that government has introduced for people, the more firmly they probably trust government's ability to manage policy-making. If, however, people find policies disadvantageous for their interests and aspirations, the less likely they are to trust government. A government whose policies permanently fail to produce benefits for people will lose the confidence of the citizens it governs.

People may also calculate the impacts of policies in the short and long term. They can trust government more if they feel assured that its policies generate willed impacts in a society. If they calculate that the outcomes of the policies will be deleterious for them and society, their trust in government is shattered. In their calculations, people may classify policy outcomes in many ways using different criteria. Figure 1 presents a simplified view of our reasoning.

Figure 1: Political Calculation of Trust

Trust in government's leadership in policy making may be either specific or diffuse. In the former case, for instance, citizens trust the objectives, principles or the means of the policy. They may also trust civil servants more than politicians or vice versa. In the latter case, people simply think that government acts in a trustworthy manner, even if they do not like every decision taken. These examples show that trust may accumulate over a long period of time.

Ministries in Political Calculation

Our main purpose is to find out to what extent citizens trust ministries as central policy-making organs at the top of public governance. They are policy-making tools in the hands of Parliament and the Prime Minister's Office. They are responsible for developing public services, regulations, and financial services. They prepare and implement the major policy decisions. They are professional organizations in their own fields.

If citizens do not trust ministries' policies, they may either passively adjust to them or try out ways to circumvent the imagined deleterious effects on themselves. These reactions increase the costs of managing policies, retard implementation of reforms and force ministries to design corrective action that consumes their scarce resources. Citizens' negative attitudes weaken ministries' images as professional organizations in public debate. Low esteem of public opinion may seriously undermine civil servants' motivation and morale causing losses that are difficult for management to compensate.

We measure citizens' trust in ministries in the following dimensions, the first of which is a generalized trust concerning the ministries' overall achievements. Second, we measure to what extent citizens trust ministries' value capability, by which we mean their ability to consistently follow certain public values. Third, we measure citizens' trust in customer policies of the ministries. Fourth, we measure the regulatory power of the ministries. Finally, we analyze citizens' trust in financial transfers for which the ministries are responsible.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143