Trust and Mistrust

|

We have argued above that bounded rationality, asymmetric information and the dynamics of sense-making are prevalent and unrestrained phenomena in organizations. They stress the importance of trust in all human interaction. They create the demand for trust. In these conditions, trust gives protection against uncertainty, unmanageability and fear of betrayal. It is a safeguard that allows time for people to learn to know each other. It provides incentives for them to act proactively, instead of preferring passivity or defending their own positions and former achievements. Trust motivates, energizes and empowers. This argument is based on the assumption that when actors recognize trust as an essential element for successful human interaction, they are inclined to provide it with their own behavior and choices and demand the same from others (Lagerspetz, 1996, p. 139). Understood this way, trust could also be compared to capital.

Defining Trust

There are different ways of defining trust, of which the intuitive definition, as it could be called, is quite common in studies in which trust is construed indirectly. This definition simply states that trust is an important factor for interindividual and inter-organizational relations without mentioning any attribute or quality (see, for instance, Lipset & Schneider, 1983, pp. 108–110; Kouzes & Posner, 1995, pp. 163–167). Authors who use this definition generally suppose that people usually know what trust is, how it functions and what kind of outcomes it produces. In this sense trust is simply the essential condition for cooperation and durability of the relationship.

The second way of defining trust emphasizes certain behavioral traits and skills as trust-creating and trust-minimizing factors. This approach is also one of the earliest ways to study leadership (Yukl, 1998, p. 234). It began when scholars believed in their abilities to recognize the traits and skills that could differentiate leaders from followers and make the former achieving and effective (Yukl, 1998, p. 234). The trait or skill approach has maintained its popularity because researchers have believed in their ability to recognize a relatively stable correlation between certain behavioral traits and managerial success.

According to this type of definition, there are certain traits and skills that could help people to win other people's confidence. For instance, people are inclined to trust people who are honest, inspiring, forward-looking, responsive and professionally capable in their tasks (see, for instance, Kouzes & Posner, 1995, pp. 13–19; Zakaria, 1999, p. 62; Annison & Wilford, 1998, pp. 5–6; Whitney, 1996, p. 16; Bidault & Jarillo, 1997, p. 85). Conversely, they will lose confidence in people and organizations that resort to telling lies, breaking promises, avoiding responsibilities and being disloyal to each other. Skills that create trust are technical, interpersonal and conceptual (Yukl, 1998, p. 235). If people want to be trusted they must also be capable of working competently and expertly (Harisalo & Stenvall, 2001b, pp. 62–64).

The third definition can be labeled a situational definition that emphasizes the dynamic and complex nature between trust and environments. Trust manifests itself differently in different situations. According to this deliberation, for instance, employees may rely on their managers for somewhat different reasons than they rely on their colleagues. Family members are probably trusted for different reasons than members of the community. It is possible that some buyers could have more trust in the personnel serving them than in the companies they work for. People may trust products and services differently from ethical principles. In all these cases there are many different causal, intervening and situational variables affecting the level of trust (Yukl, 1998, p. 267).

The definition we prefer emphasizes human interaction as a foundation of trust and mistrust. Consequently, trust is a function of the intensity, quality and durability of human interaction (see especially Harisalo & Miettinen, 1997; Harisalo & Stenvall, 2001a, 2001b; Harisalo & Huttunen, 2001; Bidault & Jarillo, 1997; Gomes, 1997; Valla, 1997; Creed & Miles, 1996). In these terms we can understand trust and mistrust by exploring the interaction between people in different organizational roles and positions and interaction between people and organizations with their value systems, policies and structural configurations. As an outcome, trust may be direct or indirect, personal or impersonal, purposeful or unintentional. Organizations are full of different kinds of real and potential relationships that could increase or diminish trust between people. The kernel of human interaction is a concrete behavior.

We hypothesize that people measure their mutual trust by three dimensions, which are: promises, commitments, and contracts. Promises are what people give to each other nearly everyday. Common examples of promises are: "I will attend the meeting," "I promise to write this paper for tomorrow," and "I will take care of this for you." Sometimes the number of promises may be quite large in an ordinary working day. To the extent people do what they have promised will help them to earn the confidence of their fellow men (Reina & Reina, 1999, pp. 144–145). People quickly learn to mistrust people who do not keep their promises.

By commitments, we mean to what extent people accept and follow the values, principles, guidelines, policies and norms of their organizations. Commitment means profound dedication to common causes based on a long-term relationship. Committed people are excited about their work, take pride in their accomplishments, and contribute to their colleagues' doing the same (Rosen, 1996, pp. 11–12). Research shows that companies to which people are deeply committed can outperform their competitors (Rosen, 1996, p. 18). Commitment is a two-way process fueled by mutual trust and undermined by mistrust. In order to earn their management's trust, people must work faster, more smartly, and more efficiently (Rosen, 1996, p. 111). In order to earn their personnel's trust, management must be committed to developing a mature and motivated workforce (Rosen, 1996, p. 18).

Contracts, written or unwritten, are meant to be fully implemented in letter and in spirit. They are an essential element in business and politics. People and organizations that follow the spirit of the contract, even if the letter would give them some benefits, are generally trusted more than those who invoke the letter against the spirit of the contract when they discover it. Probably it would be impossible to draw up a contract that would be foolproof against all potential misinterpretations. If partners do not trust each other, they will meet the rising costs of making mutual contracts.

Trust in Positional Mapping

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate trust from other closely associated concepts. If a person says he trusts someone and accepts a certain managerial action by his superior, what does this really mean? Does he mean that he is content with that person and at ease with that decision? Is it trust or something else that comes first to his mind? These are questions we try to clarify with the concept of motivational mapping in that acceptance, satisfaction and legitimacy precede trust.

Positional mapping depicts the process by which people become aware of new people and things. It portrays the learning process from elementary awareness to trust, which is the deepest or the most fundamental level in positional mapping. If they are totally ignorant about them, they do not pay any attention to problems of trust and mistrust and the learning process will not proceed.

Acceptance is the first phase in motivational mapping. We suppose that at the start, people only decide to what extent they accept or refuse to accept a person or a thing. We argue that at this moment it is fruitless to speak of trust and mistrust in them because first encounters, at best, may only reveal very weak signals about a future level of trust. If people do not accept others, it must then mean that they refuse to take any risks to learn more about the possibility of mutual trusting.

If people accept others and include them in their social interaction, the next thing that they begin to learn is satisfaction. Living up to their promises, strong commitment and honoring contracts contribute significantly to the growing feeling of satisfaction or dissatisfaction, as well as good behavior and professionalism. Growing satisfaction implies learning towards trust. Declining satisfaction predicts a critical assessment of acceptance. Dwindling satisfaction slows down or ends the learning process towards trust. Dissatisfaction limits people's chances of participating in social interaction and may even force them to step out of it (Hughes, Ginnet & Curphy, 1999, p. 421). However, if satisfaction is strengthened, people will enter the third phase in motivational mapping, which is legitimacy.

Legitimacy, the third phase of individual motivational mapping, is a psychological concept which involves stronger mental conviction than mere satisfaction than, say, a particular managerial action is right and the most appropriate for the whole organization (Kolb, 1978, p. 9). When people assess the choices of management in terms of legitimacy, they do not only pay attention to legal dimensions, but also to moral obligation. In order to earn and maintain legitimacy, management must not only be legally right, they must also be morally right. Understood this way, legitimacy manifests a deeper level in human motivations than mere satisfaction.

People learn to trust others if acceptance is followed by satisfaction, which in turn is followed by legitimacy. Thus, trust represents the deepest feeling people can have towards people and things. Our reasoning is based on the assumption that they are able to differentiate these phases. They could trust their company even if its decisions have shaken their sense of legitimacy and acted in an unsatisfactory way in a certain case. Figure 1 depicts the logic of trust in motivational mapping.

Figure 1: Trust in Motivational Mapping

Motivational mapping helps us to understand why it usually takes so long for people to learn to trust others. Trusting is a learning process that does not happen quickly. At this moment, it is difficult to describe the process in which trust turns into distrust and how long it takes. We suppose that the road from trust to distrust could often begin with diminishing satisfaction and breaking legitimacy that, uncorrected, could lead to mistrust. However, it is also possible to do something that undermines trust and deteriorates the level of legitimacy and satisfaction at the same time. These are problems that are not so far very well understood.

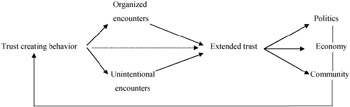

From Trust Creating Behavior to Extended Trust

We have argued that it is a learning process to trust and mistrust in a dynamic social interaction of organizations. People learn to trust their fellow men and managers and customers. They learn to trust their own organization and its division of labor, technologies, values, strategies and future standing in the markets. Social interaction provides many opportunities to learn trust and mistrust.

In organizations, social interaction is both organized and unintentional. In both of these, people can behave in a way that makes or breaks the learning process towards trust. Both encounters are important to the accumulation of trust. Figure 2 depicts the reasoning of growth of trust or mistrust in a society.

Figure 2: Trust and Social Progress

Organized Encounters in the Creation of Trust

Organizations are not only units producing goods, but also entities producing trust. They offer the most important and salient context for purposeful or organized encounters, which are, for instance, division of labor, norm obedience, group work, teams, collaboration, planning and budgetary processes and implementation of policies. Research has suggested different behavioral traits that are closely associated with trust strengthening in organized situations. The most important ways of behaving are the following five; integrity, responsibility, appreciation, competence and reciprocal support (see especially Iivonen & Harisalo, 1997).

According to Annison and Wilford (1998, p. 8), integrity is related to trust in two ways. First, people trust those who are honest. Second, people know who they are and are willing, themselves, to be sincere (Annison & Wilford, 1998, p. 9). Integrity is a primary determinant of whether people will perceive a leader or a colleague to be trustworthy (Yukl, 1998, p. 247). Unless one is perceived to be trustworthy, it is difficult to retain the loyalty of managers and co-workers or to obtain cooperation and support from them (Yukl, 1998, p. 247). Yukl argues that keeping promises and being committed are good indicators of integrity, because people are reluctant to negotiate agreements with a person who cannot be trusted to keep promises or to work for a manager who is not committed to the same project.

Responsibility, according to Annison and Wilford, incites us to trust people who behave accountably in social interaction. They go on to say that we do not trust doctors who blame others for their own mistakes, just as we do not trust managers who look for ways to shift the responsibility when things go wrong (Annison & Wilford, 1998, p. 7). It is possible to argue that responsibility for acts and choices a man has made is the great achievement of human evolution, a part of the man's destiny for which no religion, moral philosophy or ethical codes are needed. Responsibility is a reward, not servitude.

Appreciation implies trust. People who feel that they are not appreciated by their managers or colleagues have no incentive to trust them or to work for them. Appreciation empowers, while disparagement gnaws at self-confidence and sense of community (Iivonen & Harisalo, 1997, pp. 35–36). If people do not appreciate each other, it is difficult for them to share information and experience as a necessary requirement for successful collaboration. Appreciation draws and keeps people together.

Competence paves a way for trust. People like to work with managers and colleagues who are capable and effective in their responsibilities (Kouzes & Posner, 1993, p. 17). Managers must be capable of inspiring, enabling, challenging and acting and co-workers must have the technical abilities to fulfill their obligations (Kouzes & Posner, 1993, pp. 17–18). Customers value competence as a prerequisite for value-creating factors because it minimizes their costs when buying. The real problem for organizations is how to make people continually maintain and develop their competence, which requires both company policies and personal activities.

Managers and employees must show the capability for mutual support in order to earn each other's trust. People who are supportive can be unified and open to each other (Maynard & Mehrtens, 1993, p. 102). Mutual support may be encouragement, concrete help, guidance, advice and listening (Iivonen & Harisalo, 1997, p. 94). Mutual support strengthens mutuality in diversity and the community ethos. It minimizes fear of betrayal and of being left alone. This is a significant feature of the organization acting in a rapidly changing environment.

Unintentional Encounters as Trust Creation

There are numerous occasions for people to meet each other unintentionally in an organization. They meet occasionally in corridors, cafeterias and meetings and probably will never see each other again. Outside their organization they may meet accidentally in the streets, shops, sports events, public bureaus and offices and on public transport, such as buses and trains, by day or night. These experiences make them learn to trust or mistrust people they do not personally know.

There are many opportunities in unintentional encounters for people to behave so as to retain at least a sufficient level of trust among them. In the former, they are not usually afraid of engaging in different activities on different occasions. The following behavioral traits help people to earn trust from each other in unintentional encounters: anticipation, friendliness, facilitation and predictability.

Anticipation means that people foresee how their behavior could affect other people. Its purpose is to make casual interaction as easy and pleasant as possible. It is not pleasing or accepting everything. It means paying attention to one's own way of talking, making gestures and listening. Anticipation helps one to get along with strange people who could have their own and different tastes, manners and values. Anticipation paves the way towards trust and maintains at least a minimum level of trust between people who do not know each other.

Friendliness has the same purpose in unintentional encounters. It has a place in physical interaction that usually comes and goes very fleetingly. It is a behavior showing that people are well-meaning, caring and capable of creating value for each other. Everyone who risks friendliness with other people will almost certainly lose these characteristics at the same time with fading trust. Friendliness helps people to get along fairly soon in different social situations. People feel it immediately.

Facilitation in unintentional encounters means that people are willing to help unknown people when necessary. Facilitation goes a step farther than friendliness in face-to-face contacts. It is often revealed in concrete action. It is giving advice, showing the way, helping to solve problems, etc.

Predictability means behaving consistently in different situations. Expected behavior will not bring about surprises or invoke doubts about something people will disagree about or experience as unpleasant. Unpredictability means impulsiveness and instability, which makes people feel unsure or even dubious.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 143