Three Types of Inhibitors to Global Sourcing

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

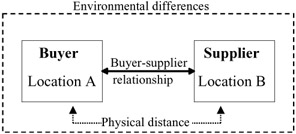

Transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1985) has attempted to sketch the costs and benefits of contracting decisions. Williamson distinguishes between two types of costs: those related to production and those related to a transaction. Production costs of most items can differ widely across countries and if only production costs mattered, firms could be expected to use an almost exclusively international supply base, given the likelihood of production cost advantages elsewhere. This is the drive towards global integration (Prahalad & Doz, 1987) that we explained above. But, as Williamson rightly notes, with the decision to set up a contract with a supplier, parties start to incur transaction costs because markets are imperfect. Transaction costs in international transactions are higher; the different locations of the buyer and supplier, unfamiliarity and the need for local responsiveness (Prahalad & Doz, 1987) all add to the transaction costs of international transactions. To be able to determine when to use global sourcing and when to use local networks, we need to determine what the total costs of both options are. We will treat the production costs at different locations as a given amount since they cannot really be changed, at least in the short run. In other words, how can we distinguish international supply decisions from domestics ones in terms of transaction costs? Three categories of transaction cost drivers in the international context will be mentioned, similar to Luostarinen's (1989) geographic, cultural and economic distance. We propose that these categories are inhibitors to global sourcing and they are in principle mutually exclusive. Geography is solely concerned with the question 'from where to where'? The relational aspects are concerned with what happens in the buyer-supplier relation itself. Finally, the environmental aspects are concerned with what happens around the buyer and supplier, i.e., the context of the buyer-supplier relation. Figure 1 provides an overall view of the three categories.

Figure 1: Three Categories of Inhibitors to Internationalization.

The first category is related to geography and how it differs between buyer and supplier. Both people and goods are imperfectly mobile, so physical distribution costs are an obvious part of geography-related costs: they are more or less linearly related to distance. Examples are increasing difficulties in logistics and physical supply, and the problems of just-in-time delivery under a global sourcing policy (Scully & Fawcett, 1994). Other costs that should be included are the coordination costs due to exchanging information over large distances, for example the costs of synchronization of business processes. As Levy (1995) describes, long delivery time may cause a product to lose value or run out of fashion, so coordination problems between the marketing and production or purchasing functions increase with distance. Another case in point is a difference in time zones, which restricts joint work in some cases. In general, the larger the physical distance, the higher the transportation and coordination costs the firm faces in international sourcing.

The second category resides in the buyer-supplier relation itself and is concerned with asymmetric information between the two parties. This has been addressed extensively in the economics of information and economic behavior theory. Individuals and organizations are limited in their ability to perceive, receive, store and communicate information. These differences cause known information to be incomplete. This is expressed in a lack of information concerning a supplier's product offerings, variations in quality standards, different business practices and language- or culture-based difficulties in buyer-supplier communication (Min, LaTour & Williams, 1994; Scully & Fawcett, 1994). An example is that frequently, buyers will not have a good overview of all available suppliers worldwide. Similarly, insufficient knowledge of a particular culture may be an obstacle in international communication. Not being able to communicate with a partner efficiently makes the building of a relationship harder. It is difficult for mutual trust to develop when partners do not know each other. This leads firms to stay within the confines of their social networks. Thus in many cases firms will not even be exposed to international suppliers, and if they are, they are less likely to choose such a supplier over a local one. Of course, as the buying firm starts internationalizing its manufacturing network through foreign direct investment, these problems may be tempered. Clearly, the more unfamiliar two firms are with one another, the more costly buyer-supplier differences are.

The third and final category consists of differences in the environments of the buyer and supplier. Having to get to know these different environments induces all kinds of deliberation costs and this phenomenon is generally referred to as the 'liability of foreignness' (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). The environment contains both business elements and institutional elements. Business elements, such as competitors, form the competitive environment, and non-market arrangements such as governments and trade unions make up the institutional environment. Political instability, regulatory and political difficulties, nationalistic attitudes, tariff barriers, trade regulations as well as different ethical standards are elements of the institutional environment that raise the need for local responsiveness (Min et al., 1994; Scully & Fawcett, 1994). Fluctuations in currency exchange rates are a part of the business environment that strongly influence sourcing decisions (Min et al., 1994). How a business system is constituted influences both the sourcing strategy of the firm as well as the location of the firm's suppliers (for Britain and Germany see Lane & Bachmann, 1996). In general, the larger the environmental differences the higher the transaction costs the firm faces in international sourcing. We posit that these three categories play a major part in determining the balance between local and global sourcing. If the strategic importance of the three categories is great (as dictated by the overall business strategy), then the leeway for strategic decision making is seriously constrained, which leads to the first proposition:

Proposition 1: The magnitude and importance of geographical, relational and environmental differences determines the feasible range of sourcing strategies in terms of local versus global.

Firms that face large and important differences when sourcing globally will be pressured to source locally. If these differences are small or not important, firms will be able to opt for a globally integrated supply chain. In the remainder of this article, we take the production cost structure of the sourcing network as a given. Instead we will focus on what happens when the costs associated with differences in location change, since that can cause the range of feasible strategies to shift. The question is in particular what happens when information technology is used to help overcome geographical, relational, and environmental differences?

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207