Introduction to Database Marketing

|

Overview

Database marketing as we know it today began in the early 1980s. Its rise was chronicled and boosted by the National Center for Database Marketing, which was started by Skip Andrew in 1987 and has continued to hold conferences twice a year ever since. At first, many com panies had heard of it, but few were actually practicing it. By 1995, however, every American company knew what it was, and most had appointed a director of database marketing. The practitioners became like religious converts. They believed in it.

Inside industry, some companies, including Kraft Foods, American Airlines (and many other airlines), American Express, Hallmark, JC Penney, Neiman Marcus, MCI, and scores of others, formed huge databases. The idea was that the company could reach its customers directly (instead of through mass marketing) and build their loyalty by direct communications. In most cases, it worked. Marketers soon learned how to set up control groups to prove whether what they were doing was working. They became skillful at what they were doing.

At first, these large databases were maintained on mainframes, with smaller databases kept on midrange computers. With the advent of the PC and servers, however, all large databases moved to servers, and small databases were maintained on PCs. Companies that kept their data on mainframes found that they were having considerable trouble keeping up with the twists and turns of the database marketing revolution.

One twist was the need to create a relational database, which is the optimum format for database marketing. What that means is that for each customer, we want to be able to keep all that customer’s transactions and demographics available, organized in tables for easy access and use in marketing. We append external data and add surveys, profiles, and preferences. The mainframe programmers just could not keep up. Today, all large databases are maintained on servers using Oracle or SQL Server. There are also a number of good database software packages for PCs.

The advent of the Web has made the greatest change in database marketing since it began. The Web has meant that

-

Marketers can access databases directly from their desktop PCs, using the Web.

-

Many companies have Web sites where customers can view and order products.

-

Customers can contact companies not only by calling toll-free numbers, but also through the Web, which saves companies millions of dollars.

-

Companies can communicate with their customers frequently at almost no expense by using email. The result is many more communications, leading to increased loyalty and sales.

-

Business-to-business use of the Web has exploded, leading in some cases to vendor-managed inventory, in which suppliers keep track of what their customers have in stock and help them to become successful.

There have been a number of wrong turns, which are described in this book:

-

Selling to consumers on the Web proved to be a major disappointment, although the Web is an excellent ordering and customer contact medium.

-

Customer relationship marketing (CRM) based on the idea of one-to-one marketing using a massive data warehouse, which many thought would be an advanced method of database marketing, proved to be an expensive failure.

-

Packaged goods manufacturers discovered that there was no profit, and in fact considerable losses, from maintaining a database of ultimate customers. The increase in sales from personal communication did not pay for the expense of the messages and the database.

-

Marketers learned that they should use their databases to create customer segments and treat each segment differently. Treating all customers alike was a loser, since customers differed markedly in their profitability.

Valuable lessons have been learned. The purpose of this book is to describe what works and what doesn’t work in database marketing. Too many books describe only the success stories without talking about the failures. In each chapter of this book, you will find a list of what works and what has failed to work.

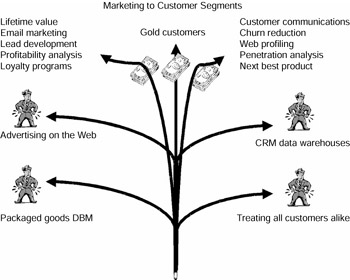

Figure I-1: What Works and What Doesn’t Work

The book contains more than 40 cases from practitioners throughout the United States, Canada, Australia, and Norway. I chose these particular cases because each of them describes the difficulties that had to be overcome and the way success was measured. Each one makes a point. Probably the key point is that success does not come from simply doing the following:

-

Building a database

-

Appending data

-

Buying expensive software

-

Running models

-

Communicating with customers

Success comes from developing intelligent strategies that build customer loyalty and repeat sales. To be successful, database marketers have to think like customers and say, “Why would I want to be in that database? What is in it for me?”

Then they have to dream up strategies that they think will build customer loyalty. They have to test these strategies on a small scale, using test and control groups. They have to be constantly coming up with new ideas because they are competing with other marketers who will copy anything that works and destroy its novelty.

Database marketers constantly work with tiny response rates. Of course, everyone has heard of marketers who have gotten responses of 20 or 30 percent, but that is very rare. Instead, 2 percent is a good response rate for a direct-mail offer, and 1 percent is a good response rate for an email offer. Some marketers get up every day and go to work knowing that they will not get better than 4⁄10 of 1 percent response on anything that they do, but they keep on going because in many cases that rate is enough for profitability.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 226