16.2 Do-It-Yourself Approach

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

In recent years, many large organizations have become more self-reliant out of dissatisfaction with the QoS and response time provided by vendors and other maintenance providers. Although the vendor community has become more aware of the service needs of businesses and is attempting to meet these needs with new and flexible programs, backed by SLAs, many are simply too small to have elaborate service programs that can respond quickly when customers experience trouble with their networks. In addition, most equipment vendors lack a nationwide—let alone international—service presence. To do so, they enter into strategic relationships with maintenance firms to ensure that an acceptable level of service and response is available to their customer base.

Many large organizations provide their own maintenance services, if not for high-end systems such as backbone routers and PBXs, then for LAN-attached equipment such as microcomputers, printers, and other peripherals. All such equipment is very sensitive to heat, static electricity, dampness, dust, grease, food and drink, and smoke. An in-house preventive maintenance program can mitigate the damage done by these contaminants, thereby prolonging the useful life of equipment and saving money on vendor-provided maintenance services.

Scheduled preventive maintenance every 100 hours or so can spot such common problems as misaligned heads on disk drives before extensive damage is done to the disks, rendering stored data irretrievable. Preventive maintenance also involves checking air filters and ventilation systems in the data center and wire closets, testing UPSs for proper operation, and periodic inspections for proper electrical grounding.

By performing their own preventive maintenance, many organizations are discovering that they can reap substantial savings in both time and money. Furthermore, the ready availability of technical training, certification programs, and comprehensive troubleshooting guides, as well as relatively inexpensive test equipment, makes faulty subsystems, boards, and chips fairly easy to isolate and fix. Of note is that the FCC’s Part 68 regulations prohibit repair or modification of registered equipment, except by the manufacturer or its authorized service agent. Failure to comply with this rule may void the warranty and possibly FCC registration. [1] Spare parts can be ordered by phone and, in most cases, same-day shipped for delivery the next day. In extreme cases, in-house technical staff can ship the faulty unit to a maintenance firm that can provide a loaner until the original equipment is repaired.

With in-house technical staff and a help desk, most problems can be diagnosed and fixed in a short amount of time, especially if they are applications problems. Users can be up and running again in a matter of minutes instead of waiting hours (or the next business day) for outside help to arrive. But in deciding whether to handle maintenance in-house, the organization must determine if it has the resources, time, and commitment to handle the job. Corporate executives must become “ diagnostic aware” and demonstrate support for the program with a realistic budget and charge telecom and IT managers with responsibility for carrying out the program.

Many companies perceive no risk at all in providing in-house maintenance services, mainly because advances in technology and production processes have combined to greatly increase the reliability of today’s communications products. In addition, many products are now modular in design, permitting fast isolation and easy replacement of faulty components from inventory. Some products even come standard-equipped with redundant power supplies, back-planes, and control logic so when the primary subsystem fails, the secondary subsystem takes over, often without users being aware of the change. While these factors contribute to the timeliness and quality of in-house maintenance, this is not to say that an in-house maintenance program will come cheaply. In fact, an in-house maintenance program requires a substantial investment in technical staff, among other things.

16.2.1 Resource Requirements

A corporate communications department is usually divided into functional areas, with each area staffed to carry out a set of responsibilities; among them, the help desk, technicians, and operations management. There are several reasons for such specialization, including the following:

-

The communications department must be able to provide the best possible response to its user community;

-

The department must have efficient and cost-effective troubleshooting procedures to minimize downtime and conserve expensive labor resources;

-

The department must have systems and network management expertise—a necessity in today’s multi-vendor voice and data communications environment.

These areas virtually demand specialized staff with an up-to-date skills inventory. Failure to divide the communications department into functional areas can jeopardize response to trouble calls and, in extreme cases, prolong the downtime of systems and networks.

16.2.2 User Support

The first level of operations support is the user support position, which is essentially the help desk. This is the first point of contact for users experiencing problems. The responsibilities of this individual or group fall into several categories: trouble reporting; handling move, add, change requests; user training; and record-keeping. This position requires individuals with demonstrated interpersonal communications skills, as well as technical competence in the use of applications, databases, systems, and networks. Usually, there will be several people with different skills manning the help desk to provide appropriate assistance.

Trouble Reporting The help desk handles troubles by doing the following:

-

Screening the problem to ascertain whether the trouble is with the user, application, database, system, or network to determine what level of expertise should be brought to bear on the problem;

-

Instructing users on the proper operation of hardware and software to prevent a recurrence of the reported problems;

-

Preparing and administering trouble tickets to identify, organize, and track problem-resolution activities;

-

Initiating and maintaining log entries to provide statistics on troubles by category on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis;

-

Monitoring trouble report escalation, according to defined response times and escalation procedures;

-

Verifying cleared troubles with users to determine level of satisfaction and service quality.

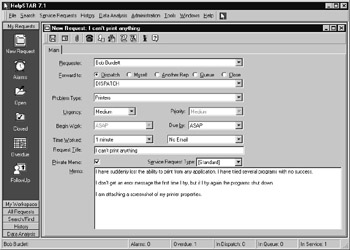

Users report problems via a “hot line” telephone number or through the help desk application accessible on a Web page (see Figure 16.1) posted on their company’s intranet. Help desk operators are usually able to answer between 50% to 70% of all calls without escalating them to another authority.

Figure 16.1: Users can submit trouble reports from a Web form posted on the company’s intranet. (Source: © 2003 HelpSTAR.com. Reprinted with permission.)

With expert systems in place, help desk operations can become more self-sufficient in handling user problems, even if a particular problem transcends their technical expertise. Basically, expert systems rely on massive databases, often called knowledge-bases, which store the accumulated solutions to a multitude of problems. Technicians, network administrators, or help desk staff can input a symptom, and the expert system will propose a course of action based on the stored knowledge gleaned from past experiences resolving problems. Some expert systems are capable of accepting plain-language input from non-technical people, who will use the plain-language output to restore malfunctioning systems or networks.

The knowledgebase is continually updated with new information from application-and communication experts, making it accessible to others when needed. Whenever the resident expert is unavailable, that accumulated knowledge and expertise can still be applied, translating users’ problem descriptions into workable solutions.

Move, Add, and Change Requests

The help desk also handles move, add, and change requests by doing the following:

-

Processing move, add, and change requests from users, workgroups, and departments;

-

Assigning dates for when the move, add, or change becomes effective and generating a work order;

-

Scheduling technicians so they can go to the right location at the right time to implement the work order;

-

Monitoring the status of work orders to ensure the completion of move, add, and change requests by their due dates;

-

Updating the help desk database to facilitate problem resolution when the problems occur again in the future;

-

Creating service orders for the repair or replacement of components and subsystems by vendors;

-

Maintaining order and receiving logs to track the movement of new equipment and software;

-

Preparing summary reports of all activities on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis.

If a problem is beyond the capabilities of the help desk to resolve, it can be escalated to a higher level of support. In many organizations, the next level of support is a NOC, which provides a global view of all networks and systems. If the problem is occurring on a carrier’s lines, for example, the NOC has the authority to interface with the carrier’s staff by issuing a trouble ticket to resolve the problem.

User Training

The training function of the help desk includes the following:

-

Providing on-the-spot user assistance and training via the help line or through a remote-control “show me” connection, whereby the help desk operator takes over the operation of a remote desktop computer to show the user how to navigate through a database or application;

-

Conducting scheduled training sessions for multiple users, either in a classroom environment or distance-learning arrangement;

-

Interfacing regularly with various department managers to ascertain the training requirements of their staff;

-

Preparing training summary reports on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis.

A potential problem is that help desk staff may lack the qualifications or background to be instructors. When allowed to go unprepared into classroom training settings, inevitably little or no learning is the result. If the communications department cannot find or cannot afford experienced trainers, they must be developed from within. Many times, any shortcomings can be remedied by “train the trainer” sessions, in which help desk staff provide the company’s professional trainers with the necessary information with which to construct courses and deliver them to end users via classroom or on-line sessions.

Recordkeeping

Documentation is an important part of administering systems and networks. This function logically extends to the help desk as well. Essentially, it involves maintaining a central library of all operations logs and reports. This usually is accomplished with the aid of software associated with other help desk functions. Typically, data is entered into various on-line forms, and the forms provide the raw information used by the report generator to issue a set of standard reports. Most software of this type accommodates SQL, so reports can be customized to meet organizational needs. In addition, the information can be exported to other applications, such as spreadsheets, for further analysis and display in various presentation formats, including pie charts, bar charts, and histograms.

Interpersonal Communications Skills

The help desk requires individuals with demonstrated communications and organizational skills, especially the ability to prioritize tasks so that they do not become overwhelmed. A sense of diplomacy and urgency are also very important. As the primary contact point for the user community, the support staff must have well-developed “people” skills so that users feel their problems are being given the attention required. The staff must also be self-motivated and self-directed to a large extent, since the workload is not set by a schedule but rather by the ringing of the phone or continuous e-mails.

Beyond the capacity for self-direction and possessing strong interpersonal communications skills, the support staff should have hands-on experience with a variety of hardware and software. After all, users require assurance that the support person is qualified to effectively handle their problems. Most hardware and software products have little quirks and nuances that are only appreciated through experience. Although this kind of information can be obtained from other support people and may even be available in the knowledgebase for easy retrieval, the need for formal cross-training may be warranted as organizations increasingly move toward multi-vendor and multi-platform environments. This situation becomes especially urgent during rough economic times, when all departments are asked to trim budgets but are expected to maintain their existing capabilities or workloads.

16.2.3 Technical Support

The next level of operations support is the technician, who may be assigned to work with help desk staff or NOC staff, either locally or remotely. The technician’s key function is to provide routine and remedial service for systems and networks through quick, efficient, and cost-effective diagnosis, troubleshooting, and service restoration procedures. The typical job responsibilities of a technician are summarized as follows:

-

Routine monitoring, which involves daily testing and adjustments to keep systems and networks optimized to handle applications efficiently;

-

Remedial maintenance, which involves problem identification, testing, and system or network restoration in response to trouble reports;

-

Preventive maintenance, which involves performing various maintenance procedures on a scheduled basis per manufacturer recommendation;

-

Interfacing with multiple vendors and carriers to isolate problems to a specific product or service;

-

Maintaining test equipment and the spares inventory;

-

Implementing move, add, and change requests;

-

Installing new systems or network components and cables;

-

Documenting all work.

Depending on the size and physical layout of an information system or network, the number of technicians and specialists required, as well as their respective skill levels, will vary. Training is an ongoing activity; in many cases, equipment warranties will not be honored unless in-house technicians have been trained by the vendor and achieve certification on specific products. The duration of such schools vary according to the type of product. A central office digital switch adapted for use on a private network, for example, may require up to 16 weeks of school at the vendor’s location. For a PBX, the training period may last up to 10 weeks; for a key system, 4 weeks; for most desktop computers, 3 days to a full week. Not only must the technician’s travel and living expenses be factored into the cost of in-house maintenance, the organization must be prepared to go without the benefit of that person’s services until training is completed.

16.2.4 Operations Management

The highest level of accountability is the operations manager, who is responsible for all operations procedures and resources and for the continuous availability of all systems and networks. This person may be in charge of the daily operations of the help desk and NOC and may report to a chief information officer (CIO). The typical job responsibilities for an operations manager include the following:

-

Oversight of all maintenance and operations functions, including fault detection; service restoration; vendor relations; software and database modifications; installation activities; moves, adds, and changes; and inventory and spares kit levels.

-

Evaluating system performance to identify any weak links or quality-control problems.

-

Evaluating vendor performance to determine if established standards, service levels, and other contractual obligations are being met.

-

Determining maintenance and equipment budgets in consultation with department heads and executive staff.

-

Determining required equipment to be ordered and any necessary system reconfigurations to accommodate corporate growth and expansion into new markets.

-

Providing technical, administrative, and policy guidance for technical staff and conducting staff performance reviews.

-

Planning, testing, and implementing mission-critical operating procedures, such as disaster recovery scenarios.

-

Establishing required service levels and response times in consultation with other departments.

In large organizations, more than one operations supervisor or manager may be required—one for telecom and another for data networks and perhaps others for the corporate intranet, information systems, and database management. In addition, there may be an entire workgroup devoted to maintaining the company’s Web site. If there is an extranet in place to share information among strategic partners, there may be a team dedicated to that operation as well.

[1]As of July 2001, the FCC no longer accepts applications for certification of terminal equipment under 47 CFR Part 68. Part 68 was originally designed to protect wire lines and telecommunications employees from harm, while fostering competition. It called for the phone companies to allow other manufacturers’ terminal equipment to be attached to their wire lines if the terminal equipment complied with Part 68, ensuring that the equipment would not damage the wire lines or harm personnel. The FCC decided that with the speed of technological changes and advances in the telecommunications industry, it would no longer micromonitor each piece of equipment. The Administrative Council for Terminal Attachments (ACTA) is now the body responsible for establishing and maintaining a database of equipment found to be compliant with industry-established technical criteria, establishing numbering and labeling requirements, and establishing filing requirements for certification.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 184