Story-Driven Character Design

| The best approach to developing a well-fleshed-out character is to start with the story behind the character and develop the character's traits and personality before you even consider the appearance. Often artists prefer to work from a detailed description such as this; it allows them to really understand and visualize the character. Even games that you would not expect to have fully developed characters can gain much by including them. Consider the multi-format title SSX Tricky , shown in Figure 5.8. This is an extreme sports snowboarding game that pays attention to character development. The player is allowed to make friends, foster rivalries, and enhance her character throughout the game. The addition of this storylike element enhances the game above the simple level of a straight sports game. The player chooses the preferred character and begins to identify with her. This causes a greater sense of immersion in the game ”and best of all, it's not prescripted. The player can choose who to make friends with and who to antagonize, and it does have an effect on the gameplay. You can be sure that anyone who you make an enemy of will try their hardest to sabotage your run ”and there will be a few sharp words exchanged at the finish line. Figure 5.8. SSX Tricky. Admittedly, it's not complex stuff ”it could be taken further ”but it's refreshing to see this sort of thing being attempted in the sort of games in which previously it was unheard of. Interaction between characters is one of the most interesting aspects of stories ”sometimes more so than the actual plot. Although a plot details the path of a story (we cover this in the next chapter), the character interactions add a lot of flavor and subtlety that differentiate a well-crafted story from a fifth-grade English composition assignment. One of the major problems with the games industry when it comes to character design and story content is our unoriginality. We are quite content to plagiarize our characters wholesale from other media, and we are almost afraid to develop original characters in their own right. For example, Lara Croft is simply a female version of Indiana Jones, except that she doesn't have anything like the depth of Indy ”his vulnerability, weak spots, and so on. If he is two-dimensional, then she is one-dimensional. Lara eminently demonstrates that not only are we ripping off the movies, we're also doing a bad job of ripping off the movies, as far as characterization goes. Joanna Dark (from Perfect Dark ) is a female version of James Bond (or any other secret agent you prefer). As the industry gets bigger, game designers can no longer borrow ideas wholesale from other industries. They will need to carry themselves as an original art form, unless they want to suffer the same fate as the British movie industry ”meagerly surviving on borrowed concepts (and borrowed time). Of course, this is a black picture to paint and is unlikely to come about in the extreme case. The games industry has survived one big crash so far, back when Atari went down the pan, and the resulting slow consolidation of the bulk of the industry into a small group of giant conglomerated corporations has done little to aid creativity. Character DevelopmentThe primary indicator of good characters in any medium is how well they develop and adapt to changing circumstances. Language is a key cue to a character's personality. His grammar and vocabulary send all kinds of signals ”about his social class, education, ethnic origin, and so on. These, in turn , connect with patterns ”or stereotypes, if you prefer ”in the player's mind. This is also true of the character's accent . One of the most interesting uses of this in recent years was in Starcraft , which drew on a variety of American accents to create several different types of characters. Although they did include the "redneck Southerner" stereotype, which was regrettable but practically inevitable, they also included the "Southern aristocrat" and "Western sheriff" speech patterns for Arcturus Mengsk and Jim Raynor, respectively; the laconic, monosyllabic diction of airline pilots for the Wraith pilots; a cheerful, competent Midwestern waitress for the pilots of the troop transports; and a sort of anarchic, gonzo biker for the Vulture riders. This gave the game a great deal of character and flavor that it would have otherwise lacked if it has used bland , undifferentiated voices. If a character is flat and one-dimensional, then it shows. Sometimes this can be the desired effect, especially in the case of comedic computer games. Consider Duke Nukem, a muscle-bound, blond-haired, misogynist killing machine. You would not expect him to develop his sensitive side and start calling his mother halfway through the game. In this case, his one-dimensionality is funny ”it's used well as part of the game. It also allows the player to easily slot himself into the role, knowing that it will remain consistent. This works so well because the player is glimpsing only a limited part of the life of Duke. For the player, it is part of the fun for him to play the role of a thinly motivated hero. Of course, this is also dangerous ground to tread upon. This sort of thinking landed Doom an ( undeserved ) starring role in the lawsuits following the Columbine tragedy back in 1999. Notwithstanding the fact that blaming the escapist world of a computer game for encouraging this sort of tragedy is simple witch-hunting, we should be aware that the games industry is a prime target for litigation. Computer games are still looked upon as "entertainment for children," and even though this is no longer true, we need to do more to encourage the maturation of the art. One way to do this is to tackle serious subjects in a mature fashion, with the benefits of good character development and story lines. One way not to do it is to tackle serious subjects in an immature fashion, as Postal and, to a lesser extent, Soldier of Fortune did (see Figures 5.9 and 5.10). Figure 5.9. Postal. Figure 5.10. Soldier of Fortune.

Soldier of Fortune's main advertising thrust was the ability to accurately shoot individual body parts . It's fine to have this as a game feature, as long as it's appropriately marketed. It should not be the primary focus of the advertising because it does not add much to the gameplay. The focus of the marketing should be the story and gameplay, not the realistic deaths. The game would still play the same (a standard first-person shooter) with or without the accurate body part “shooting capabilities. It's the difference between marketing a mature game and a murder simulator. That doesn't mean we can solve all these problems by making our characters shed a tear when they kill. In general, though, treating these subjects with a bit more care and attention will improve their perceived value to the outside world. Develop Believable CharactersDeveloping believable characters is not a straightforward process. Although there is no surefire method, there are three golden guidelines to developing effective, believable characters:

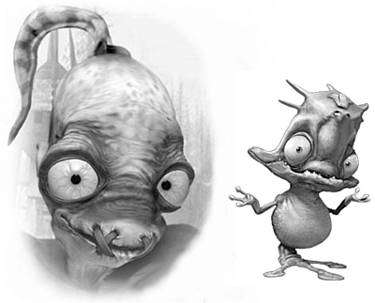

These rules are fairly obvious. If a character does not interest the players, they aren't going to play the game. Similarly, if the players don't develop an affinity for the character over time, they will not be particularly sympathetic to the hero's plight ”and, consequently, won't be particularly compelled to take part. Generally, the first two guidelines are followed pretty well ”or, at least, attempts are made. The previously mentioned Bubsy the Bobcat fails on all counts. The third guideline is the one that seems to fall by the wayside. Although it is fairly easy to invent an interesting character that conforms to the first two guidelines, it's far more difficult to develop that character further so that it develops and grows realis tically. If it were that easy, a lot more people would be writing best-selling novels . Growth of the CharacterOne important consideration for realistic characters is based on the diagram shown in Figure 5.11. The growth and progression of the hero is an important part of the story ”as important, if not more so, than the plot itself. Figure 5.11. Character growth cycle. The common character growth cycle that is tied in with the Hero's Journey advises how to manage the growth of the hero character. The hero starts with a limited awareness of himself and his situation. As the story unfolds, the hero's awareness increases to a point at which he realizes that a change is necessary. At this point, the hero often exhibits a reluctance to change ”the point at which he would be leaving his ordinary world and entering the special world ”and has to dedicate himself to overcoming his reluctance. The point at which the hero has committed himself to change usually signals the end of the first act of the story. After the hero has entered the special world, he experiments with his new environment, trying to discover the rules and customs that will allow him to prepare effectively for his adjustment to the special world ”his big change . This point usually marks the end of the first part of the second act. From this point, the story winds up toward the climax point of the second act by showing the consequences and setbacks of the hero's first attempt at change. The third act starts with the rededication of the hero to the efforts to change. Here, he makes his final attempt , resulting in a mastery of the circumstances of the special world, closing the cycle and finishing the story ”and the development of the character. The various martial arts are a field full of Eastern traditions, with each style encompassing its own unique set of traditions, with many of these often traceable back to a single root. Common to most of these arts is the venerable black belt, the symbol of mastery of the art. These belts are constructed in such a way that over time, the black thread of the belt wears out and the white of the underlying material shows through. Contrary to initial appearances , this is not just a sign of shoddily made belts: It is representative of a tradition rich in symbolism. The painful transition from novice to master ”from white to black ”is a hero's journey. The symbolism of the black belt fading to white is to indicate that the master is, in fact, a novice at a new higher level. The master has an understanding of the physical aspects of the art; now he can start again and learn the spirituality behind them. The symbolism is beautiful: The master is still a novice, and the path to mastery is cyclic. In addition to this, martial arts tradition never originally called for colored belts. Rather, a white belt gradually became brown and then, over the years, black. This was a sign of experience. At the end of each session, the martial artist would wipe his sweat with the belt. This same analogy is often applied to the hero's character development. That's why the diagram shown in Figure 5.11 is a circle. The hero, having achieved mastery of the special world, becomes a novice of circumstances in a new special world. This is the mechanism that is often used to create effective sequels. This is a difficult concept to grasp, and it is even more difficult to implement well. Don't be too discouraged, though ”some common techniques for effective character development are summarized at the end of this chapter. However, before we get to this new material, we need to cover some of the common character archetypes found in stories. The Character ArchetypesAccording to classic literary theory, a number of character archetypes crop up in some form in most stories. This section covers these archetypes and describes their nature and roles. These archetype definitions are taken from Christopher Vogler's The Writer's Journey , a treatment of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey aimed at screenwriters , as discussed in the previous chapter. The common archetypes are not restricted to a single character in any particular story. The same character can play any number of different roles. For example, the character playing the mentor could also be an ally, a herald, a threshold guardian, or even a shadow at a different point in the story. This is how good drama is constructed. HeroThe hero is traditionally the center of the story. In our case, the hero is the player's avatar. In literature, the hero is traditionally a character with one or more problems. The story tells how the character solves these problems. This apparently simple pattern is the basis for all stories. In general, stories revolve around a conflict and the resolution of that conflict. This is where the hero fits in. The most important thing to do with the hero is ensure that the players can identify with the character. The hero should have qualities that the players can appreciate and empathize with. The hero's goals should become the player's goals. How you choose to implement this depends very much on the nature of the hero. For example, in Oddworld: Munch's Odyssey, the two heroes, Abe and Munch (shown in Figure 5.12), certainly don't win any beauty awards, but they still appeal successfully to the player. Figure 5.12. Abe and Munch. There are a number of possible reasons for this. Note that both Abe and Munch follow the super-sensuality guidelines mentioned earlier, with large eyes and big foreheads, echoing those of babies. Despite (or perhaps because of ) their ugliness, and the fact that they are enslaved underdogs of a much uglier ruling class, they appeal to a wide range of players and have been a surprising success. It's surprising, that is, for the developers. However, close examination of the archetypes and the characteristics of Abe and Munch (as well as the quality of the games in which they were introduced) indicates that the success isn't as surprising as it might initially seem. Of course, as we stated in our guidelines, after the initial interest has been created, it has to be maintained . One of the primary methods for doing this is to make sure that the hero changes and grows during the course of the game. Depending on the style of the game, this could be a real growth ”in personality and demeanor ”or a more straightforward approach, such as with power-ups and improvement of characteristics. The latter method is far more common in games, although some games do make use of the former to some extent. Planescape: Torment is a specific example that springs to mind, even though it uses standard stats-pumping growth, too. The main defining characteristic of a hero in a story is that the hero performs most of the action and assumes the majority of the risk and responsibility. This doesn't mean that other characters can't take the mantle of hero temporarily. For example, in cut scenes, they might be shown sacrificing themselves for the hero. Perversely, the hero doesn't necessarily have to be heroic: The antihero is also a classic motif. The Dungeon Keeper series of games uses this particular form, in which the aim of the game is to destroy the forces of good. Heroes are not always on their own. In some games, the "hero" is represented by a group of individuals: the hero team. These are common in role-playing games. Often, though less frequently nowadays, character development in hero teams is limited; in the case of role-playing games, they are computer-generated characters created and customized by the player. However, when hero teams are used in multi-player games (such as Diablo and Diablo II ), each player represents an individual hero. In single-player games, the player tends to pick a "favorite," and that character becomes her avatar. Sometimes games even mandate this choice for the player; examples of games that do this are Baldur's Gate , Planescape: Torment , and Anachronox (shown in Figure 5.13). Figure 5.13. Anachronox. In fact, Tom Hall's Anachronox is one of two excellent games that came out of Ion Storm. ( Deus Ex is the other.) Unfortunately, by the time these games were released, the well had already been poisoned by the lamentable Daikatana (starting with the infamous "John Romero's about to make you his bitch" advertising campaign). The hero of Anachronox , Sylvester (Sly) Boots, is a down-on-his-luck private detective who is being harassed by the local mob to pay back some debts . Sly Boots is a good example of a hero because, characteristically, a hero can be made more appealing by giving them a vulnerability. Heroes often have an inner problem and an outer problem. These can shift as the game progresses. The outer problem is the general quest that is the aim of the game. The inner problem is usually something personal to the hero. In Sly's case, his vulnerability is his debt. At the start of the game, Sly is being beaten to a pulp by a goon. His vulnerability is his lack of cash, so the first task for the player is to help him find a job. Initially, this is his outer problem. However, as the game progresses, this morphs into a grander quest to save the universe. Sly's inner problem is that he is a low-life. This affects the attitude of the other characters in the game toward him and serves to make the quest more difficult than it might have been otherwise. More important, it adds an extra dimension to the character that creates an air of believability. In summary, the hero's outer problem can be stated as the aim of the game, whereas the inner problem is a character flaw or some other dark secret. The player might not even know the inner problem at the outset. Planescape: Torment uses this particular mechanism well. MentorThe mentor is the guide character. It can come in many formats: the clich d wise old man or woman , the supernatural aid, or even the hero's own internal voice. The most familiar example of this that will spring to mind for most people is the character of Obi Wan Kenobi and his relationship with the would-be Jedi, Luke Skywalker. Anachronox uses the mentor archetype brilliantly: Boots' mentor is his dead secretary. After she dies in some unspecified accident , Sly had her brain digitized and stored in a small device called a "life-cursor" (which also doubles as the player's game control cursor). This allows her to continue to function as a secretary, with the added benefit of being hooked into the world's computer systems. This also allows her to manage the adventure bookkeeping, providing timely advice and hints to Sly, and acting as a story guide to seamlessly keep the hero within the bounds of the designer's gameplay plans. Mentors are not always positive. A mentor can also give bad advice deliberately designed to mislead the hero or to lead him down an evil path. A classic example of this form of "dark mentor" is the devilish advisor in Peter Molyneux's Black and White . Higher SelfThe higher self is the hero as he aspires to be. It is the ideal form of the hero. In many cases, the object of the game is to transform the hero into his higher self. Of course, this is not explicitly stated as a gameplay aim, and it usually happens as a side effect of completing the game. There are many examples in role-playing of this particular motif. For example, the whole premise of Planescape: Torment is based on the transmutation of the Nameless One into his higher self. He is a character with amnesia but a distinct past, who seeks to regain his name and his memory. In the process of doing so, he might also have amends to make to people he has hurt in the past. AlliesAllies are those characters placed in the game to aid the hero. Many games use the ally archetype. The aim of the ally is to aid the hero in the quest and help to complete tasks that would have been difficult or nearly impossible without aid. Han Solo is the classic example of the ally archetype that most people know. We are sure you can think of many examples of this because it is one of the most common archetypes. An obvious example is the role of the scientists and security guards in Half-Life . In many instances, they team up with the hero, Gordon Freeman, to provide advice and help him get past obstacles, such as doors with retina scanner “based locks. Shape ShifterThe shape shifter is the most elusive archetype used in stories. The role of the shape shifter is to appear in one form, only to be revealed later in the story as another. It's a catch-all transitional archetype that governs the transformation of characters. For example, an ally or mentor could turn out to be a trickster or a shadow. A character that initially helps a player could turn out to have been acting in his own interests, finally betraying the hero when his aims are achieved. An example of this archetype from classic literature is the evil queen in Snow White . She appears to Snow White as an ally and mentor (the wizened old woman with the apples) before revealing herself to be a shadow and a trickster when Snow White is poisoned. An example from a game is the White Lord from the old role-playing game Dungeon Master . The White Lord initially acts as a mentor/herald, tasking the adventurers to enter a dungeon and seek out and destroy the Black Lord. If they achieve this, then upon return to the surface, the White Lord declares that they have been tainted by the evil of the dungeon and attempts to destroy them (becoming a shadow). Threshold GuardianThe threshold guardian is another very common archetype used across the whole spectrum of game types. The role of the threshold guardian is to prevent the progress of the hero by whatever means are necessary ”at least, until the hero has proven his worth. Sometimes the threshold guardian appears as a lesser form of the shadow archetype, maybe as a henchman or a lieutenant of the main shadow. The most obvious example is the classic end-of-level boss used in virtually every arcade game since the Creation. A more subtle use of this archetype does not use force to dissuade the hero. It could be voiced by the hero's own self-doubt, or the warnings and ministrations of a mentor character. Consider the role of Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back . Although he acted as a mentor in training young Luke in the ways of the force, he also cautioned strongly against Luke leaving to face Darth Vader. Luke's training had not been completed, and he was not yet ready to face his nemesis. TricksterTricksters are often neutral characters in storylines who delight in making mischief for the hero. They can also make an excellent (incompetent or otherwise) sidekick for the hero or the shadow, giving an easy opportunity to inject some comic relief to lighten the storyline. There are many examples of trickster characters that we can draw on. For example, Bugs Bunny from Warner Brothers cartoons is one; Wile E. Coyote is a trickster, too, but his tricks always fail, or the Roadrunner out-tricks him. The trickster is someone who achieves his ends through cleverness , resourcefulness, or lateral thinking, especially in the face of superior force. Actually, this could be said of the hero in a fair number of adventure games; the puzzles represent the "tricks" in a way, especially if they're set up that way. For example, the hero often has to trick a threshold guardian into leaving the threshold. In a way, this was the role of Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit : He wasn't brought along on the adventure for his strength, but for his cleverness, which was eventually augmented by the Ring that made him invisible. ShadowThe shadow is arguably the second most important character after the hero himself. In some stories, the shadow is elevated to the number-one rank. For example, Ritual Entertainment's Sin 's main selling point was the shadow, Elexis Sinclaire, a beautiful, sexy CEO of a massive bio-tech corporation who happened to have a penchant for clothes and makeup that wouldn't appear out of place on a street-walking extra from the film Pretty Woman . Aside from the fact that the biographical details for Elexis Sinclaire (shown in Figure 5.14) are straight out of a (bad) schoolboy fantasy, the emphasis of the game is on her as the primary character in the game. Figure 5.14. Elexis Sinclaire. In other games, the shadow lives up to its designation ”remaining mysterious until the story climax, when it is revealed in a flourish and a flash of lightning. This can add a lot to the gameplay, especially because part of the gameplay is often to find out the identity of the shadow. This can add a lot of dramatic tension and mystery to augment the gameplay. The shadow is the ultimate evil, the great adversary that is responsible for the hero being in the predicament that he is in. Sometimes this is a personal decision: The shadow has a vendetta against the hero. In other situations, the shadow doesn't even know of the hero, and only the actions of the shadow affecting the hero on a personal level spur him to action. Of course, the shadow doesn't even have to be a concrete entity: It could be just a set of circumstances or feelings within the hero himself. His own dark side could be the shadow. HeraldThe herald archetype is used to provide the hero with a change of direction and propel the story in a different direction. The herald is often used to facilitate change in the story. Princess Leia's message to Obi-Wan Kenobi that Luke discovers in R2D2's memory serves this function. It's unclear whether Princess Leia or R2D2 is the herald, but it doesn't really matter: Luke gets the message from a figure who provides his necessary "change of direction." Another example is the voice of the narrator in Dungeon Keeper. This could be described as a herald: He describes the challenges to be faced in the level ahead and keeps the player appraised of the progress of the campaign. The function of a herald is to provide a motivation to the hero to progress in the story. Heralds can be positive, negative, or neutral. It doesn't need to be the classic herald of Greek literature. In fact, the herald doesn't have to be a character at all: The call of the herald could simply be a set of tricks to mislead the hero into a certain route or path.

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 148

- Enterprise Application Integration: New Solutions for a Solved Problem or a Challenging Research Field?

- Data Mining for Business Process Reengineering

- Intrinsic and Contextual Data Quality: The Effect of Media and Personal Involvement

- Healthcare Information: From Administrative to Practice Databases

- Relevance and Micro-Relevance for the Professional as Determinants of IT-Diffusion and IT-Use in Healthcare