Chapter 7. Inspired Decisions

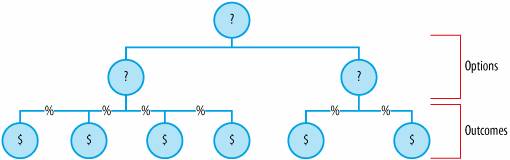

I remember the summer of 1989. I was 19 years old, a sophomore biology major at Tufts University, and a transient in the home of my parents. My passions were, in no particular order, soccer, girls, literature, beer, and artificial intelligence. My summer began in the environmental lab of the Millstone nuclear power plant, where I measured the impact of thermal discharge on marine biodiversity. By day, I studied sand under a microscope, and by night, the works of Dostoevsky, Turing, Hofstadter, and Dennett. That August, we took a family vacation to France and England. I left the sand behind, but the self-reflections of The Mind's I and the eternal golden braids of Gödel, Escher, Bach traveled with us. In fact, one of my fondest memories is of wandering with my brother through strange loops and tangled hierarchies, surrounded by the rolling green hills of the English countryside. Thinking machines, disembodied minds, silicon souls, selfish memes: we were intoxicated by metaphorical fugues, and a few pints from the local pub. It was during these forays into artificial intelligence (AI) that I first stumbled into decision trees . A decision tree, like that shown in Figure 7-1, is a graph of choices and possible consequences. In theory, by identifying options and outcomes, and multiplying the probability and value (minus cost) of each outcome, we can reduce decisions to quantitative analysis. Of course, their utility isn't limited to humans but holds great promise for AI. After all, rational choice has long been held as a sign of intelligence. So naturally, the roots of AI, and the big wins in expert systems and game algorithms, are flush with decision trees. In fact, it was Deep Blue's ability to evaluate "leaf positions" at a rate of 200 million moves per second that enabled victory over Gary Kasparov in 1997. Before that match, the chess champion said "I'm playing for the honor of the human race." Afterward, Deep Blue remained silent. Figure 7-1. A simple decision tree In the last half century, the prospect of thinking machines inspired significant research and novel insight into the constitution of real intelligence. So it's both natural and ironic that Herbert Simon, a founding father of the field of AI, struck the mortal blow to the classic model of rational choice and the broad applicability of decision trees. In his 1956 landmark paper, this Nobel Laureate and A.M. Turing Award recipient employed a simple organism's search for food as a metaphor for decision-making:

He argued that within a framework of fuzzy goals, imperfect information, and limited time, our partly rational minds adapt well enough to "satisfice" but don't generally optimize. Simon's radical theory of "bounded rationality" led not only to the demise of "homo economicus," but also to appreciation for the intricacies of human intelligence, because the simple rules of chess don't apply to the complex decisions of real life. Simon's work anticipated the difficulties of AI, though he never gave up the dream. In an interview not long before his death in 2001, he was asked whether a computer might someday deserve a Nobel. In response, Simon said: "I see no deep reason why not." |

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 87